Features

Features

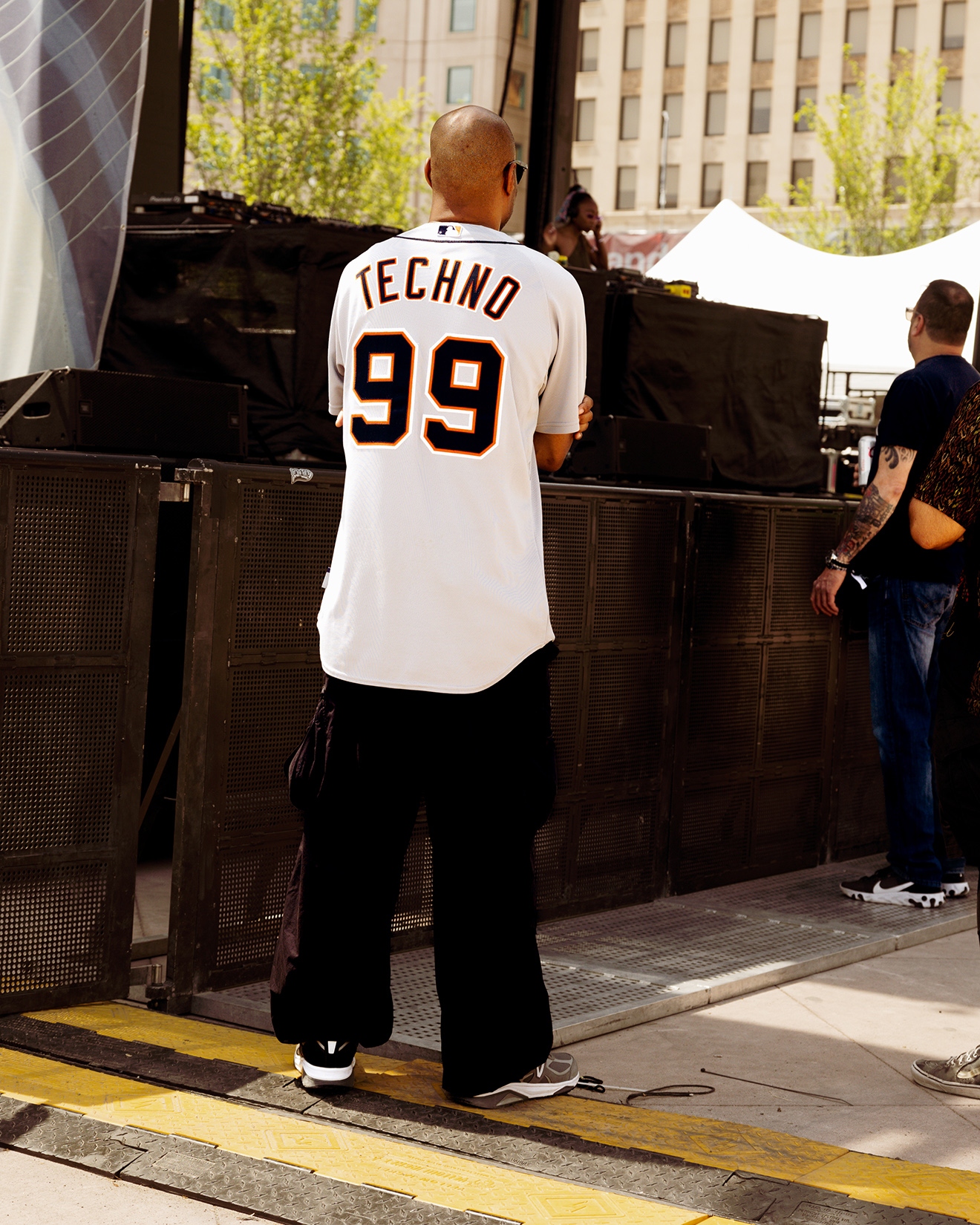

Movement Festival is a celebration of techno's past, present and future

Held in Detroit, the birthplace of techno, the three-day festival should be on every clubber’s bucket list

On Memorial Day weekend in Detroit this year, Kenny Dixon Jr. was on a mission. Better known as Moodymann, one of the city’s most beloved producers was out to spread the gospel about another legendary local, an architect of Detroit techno.

“If y’all know who Juan Atkins is, make some noise!” he implored the crowd at the Stargate stage at Movement Festival on Saturday afternoon. “Juan is the big one in Detroit.” This followed similar comments made during a conversation with DJ Stingray 313 (Sherard Ingram) in Detroit on Thursday evening, where Ingram interviewed Dixon Jr. about his favourite records. “I’mma tell you something about the big three, and we all know who the big three is, that’s GM [General Motors], Ford and Chrysler,” Dixon ribbed. “The second big three is something that European [sic] gave, and we all know who that is…but if you ask any Detroiter, there’s no such thing as the big [Belleville] three, there’s only the big one. And that’s Juan motherfuckin’ Atkins.”

Read this next: Uncovering Moodymann's Detroit hip hop origins

As with most origin stories, this account is contested. Richard "Rik" Davis, former leader of seminal electro/techno duo Cybotron, released a solo deep space record, 'Methane Sea' in 1978, then wrote much of the music and lyrics for Cybotron before Atkins departed in 1985 (Davis went on to release two more Cybotron albums in 1993 and 1995). And as Dixon Jr. alluded to, it’s reductive to suggest that Detroit techno was created by just three men. But quibbles over who can lay claim to “creator” status don’t negate an essential truth: Detroit was a site of electronic music innovation in the ‘80s, its Black artists forging unique, futuristic sounds so compelling they were taken back to Berlin and proliferated across Europe, influencing permutations of techno in the decades to come. Juan Atkins is inarguably a pillar of Detroit techno, and was the first of the Belleville Three to DJ and produce (the name “techno” comes from a Cybotron track, 'Techno City').

On Sunday night at Movement Festival 2023, Atkins was justly celebrated as the current touring version of Cybotron (Atkins, Tameko Williams and Laurens Von Oswald) played what was only the group’s sixth live show ever, and their very first performance in Detroit. Despite some technical difficulties, it was a majestic, mesmerising set that attracted the crowd it deserved to the main stage for an hour of timeless Afrofuturism (see 'Clear', 'Cosmic Cars' and 'Alleys Of Your Mind'.)

Robert Hood followed for what was the festival’s strongest one-two punch, and Hood’s only live performance of 2023. The former Underground Resistance member and ordained minister led a sermon of perfectly programmed techno as punishing as it was cleansing, his distinguished presence on stage (that hat! that aura!) heightening the sense of ceremony.

Read this next: Movement Festival shows Detroit is still leading the way for techno

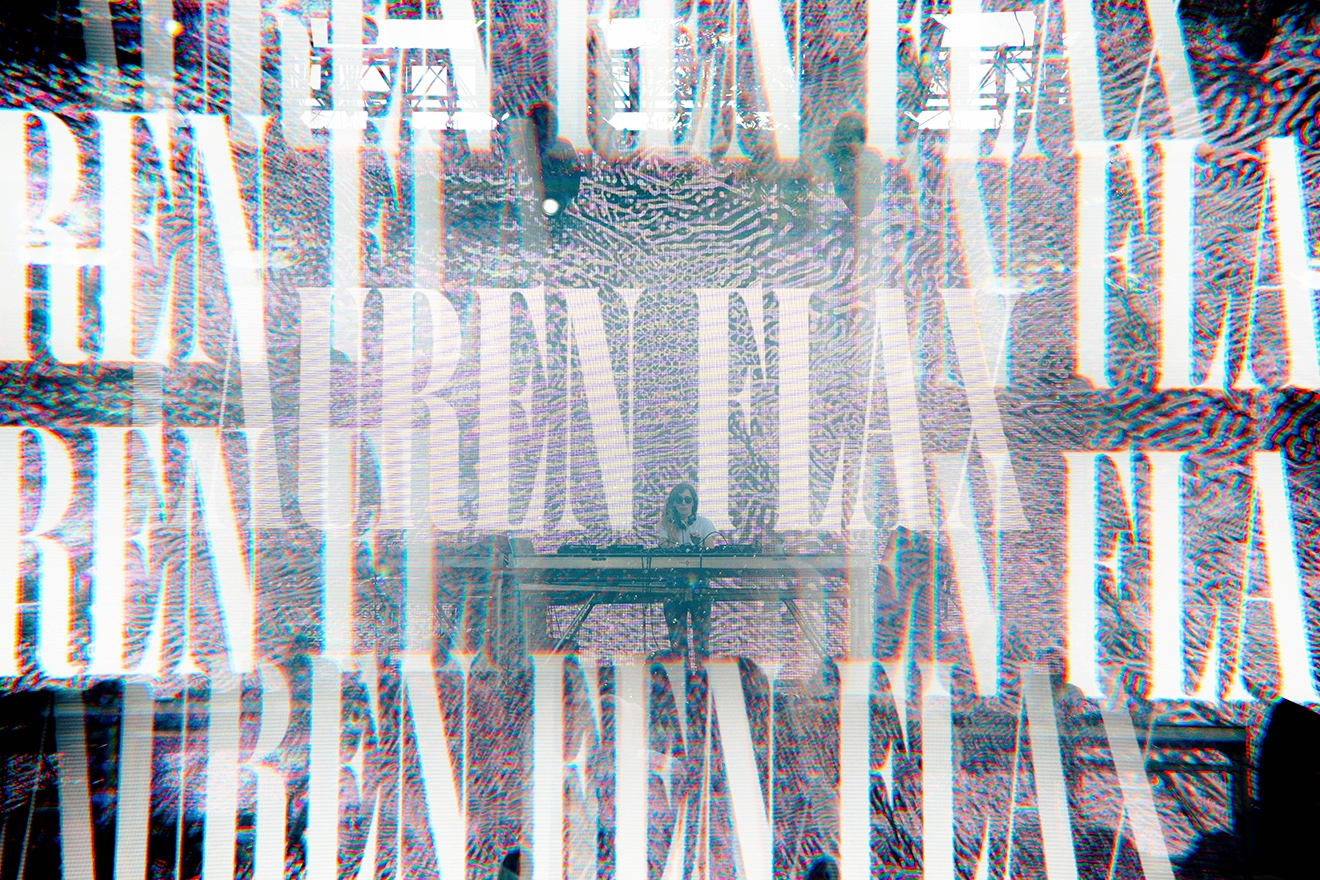

Those who stuck around after Hood’s set (a large, transfixed crowd) would’ve seen Belgian superstar Charlotte de Witte become the first woman to headline the main stage at Movement. Some, including myself, might’ve deemed Detroit royalty DJ Minx a more fitting recipient of the honour. But such is the nature of Movement’s juggling act, trying to attract young fans with the likes of international juggernauts de Witte, Fisher, John Summit b2b Dom Dolla and Skrillex while treating the Detroit techno veterans with the reverence they deserve (on Saturday, Minx hosted her own stage for the second time this year with a blockbuster line-up including TSHA and Derrick Carter playing b2b with Mark Farina, and a primetime set by Minx herself). For the most part, Movement promoters Paxahau manage this delicate balance well. And if scheduling de Witte directly after Hood might introduce young attendees to the Detroit legend via the tail end of his set, it’s not a bad outcome.

Despite being a predominantly techno festival, there was something for every kind of electronic music fan on the bill this year, and a spoil of talent meant you sometimes wanted to be at all six stages at once. On day one, Basement Jaxx’s DJ set clashed with sets from Memphis hip hop icons Three 6 Mafia, Carl Craig ft. Jon Dixon live, Surgeon, Masters at Work, and AUX88 live. And while Robert Hood was holding Sunday service on the main stage, Ela Minus, KiNK (live), DJ Nobu, Ricardo Villalobos and Scan 7 (live), were playing on other stages.

The depth and breadth of acts over the weekend — from Caribou to Uniiqu3 to LSDXOXO to Sinistarr to Kaskade — also ensured there was almost always a sizable crowd for every artist (over 115 acts in total). The main stage is naturally home to the biggest draws/most significant artists, the Pyramid and Stargate stages are mostly house-leaning, the Waterfront stage, with a gorgeous view of the Detroit River, mainly hosts artists that don’t slot in easily elsewhere, while the Underground stage is a proper techno bunker and the perfect spot for the hardest acts on the bill.

Read this next: Grandma Techno: "I love the energy. Techno feels like the hippy movement in the 1960s"

More than 30,000 people attended each day of Movement this year, and while you certainly felt the crowds during the festival’s busiest moments, this had nothing on the first couple of years in 2000 and 2001, when it was known as Detroit Electronic Music Festival, was free, and reportedly attracted 1-1.5 million people. Stacey “Hotwaxx” Hale, godmother of house music and one of the first women DJs to mix continuously, recalls the inaugural edition.

“The first was more family-oriented, there were families dancing, it was very organic.” 22 years on, the festival is more “mechanical”, she says. “It’s doing its best to be more organic and it is somewhat, but we’re doing very adult things here. I mean, look at the sponsors,” she says, gesturing at the stand for JARS, a cannabis dispensary giving out free joints. “But they’re running a business, you have to do the things to generate dollars to pay for this.”

Like many of the Detroit OGs, Hale is playing a bunch of shows in the days before, after and during Movement. “It’s DJ Christmas in Detroit,” she says of the last week in May. “There’s so much work for a DJ and it’s so embraced, there’s not another time like that ever.”

Eddie “Flashin” Fowlkes, one of the progenitors of Detroit techno and the godfather of techno soul, played a sexy, bumping house set on the main stage on Saturday afternoon. He also recalls the first DEMF fondly, an event where he DJed alongside a keyboardist, drummer and the same hype man used by George Clinton. It’s a very different festival now, he says.

“Some of these cats come into town, they don’t really know the Detroit sound, they’re getting paid $15-20k, they’re playing Detroit today, New York tomorrow, Montreal…I know plenty of dudes come in that have never experienced Detroit, no Motown museum, they just take the money and run.”

“When I go to Berlin there are certain things I won’t play, they’ve got a certain type of music that I respect. When I go to London, same thing. You’ve got these people coming to Detroit but they don’t know Detroit music.”

Read this next: The Beneficiaries: "We are resistance artists, techno is resistance music"

Of course, many out-of-towners do understand and appreciate the significance of playing Movement in the birthplace of techno, but there are definitely others who don’t appear to. Fowlkes also takes issue with the whitewashing of techno more broadly, and the derivative, more commercial forms of the music he helped create, music that was born from oppressive conditions.

“It’s a disrespect to our culture,” he says of the indiscriminate application of the word techno today. “You weren’t dodging bullets and robbing motherfuckers just to get a 909.”

Many of Detroit’s finest producers were also employed in the automotive industry, which, as well as partly explaining techno’s industrial crunch and clatter, might have encouraged some artists’ prolific output and ability to create under pressure. Octave One, active since 1989, consider themselves in the latter camp. The duo of siblings Lenny and Lawrence Burden (other brothers Lorne, Lynell and Lance sometimes contribute to productions) would only start working on albums two days before they were booked to be mastered.

Octave One were part of the second wave of Detroit techno artists, and their live set on Saturday night showcased both the range of their sound and their decades of experience. Hammering, hard-as-nails techno, much of it adapted from their new album 'Never On Sunday', was seamlessly arranged alongside more melodic cuts including their best-known track, the 2000 lilting club anthem 'Blackwater'. There was soul even in the set’s toughest moments, however, something the brothers credit to the soul music their parents would play to them as children. “The fact that we could make a whole song ourselves with a drum machine and synthesisers, we were doing electronic versions of soul music, that’s always been a part of us,” says Lenny. Their shows are live in the truest sense; completely improvised (yet stunningly fluid and cohesive). “We don’t have a set list, we know what the intro is gonna be, but we make it up right there,” says Lenny. “One of the tracks 'Contemplate', that was the first time we played it live tonight,” adds Lawrence, who waits for Lenny’s cues then produces on the fly. “I like to be on the edge, I don’t want to be counting 1, 2, 3, 4,” he grins.

As well as the healthy amount of Detroit artists who performed on the main stage and across the festival this year, there was also a dedicated Detroit stage celebrating local (and often legendary) talent — a spread of young and veteran artists playing everything from vinyl house sets to footwork to EDM/bass. The stage was perhaps strategically located near the festival entrance/exit where acts might attract passers-by as well as their fans. Here I saw vinyl maven Whodat (Terri McQueen) play sunny, upbeat house records, Rebecca Goldberg lay down a squelchy set as 313 Acid Queen, and Sillygirlcarmen, a protégé of Delano Smith, charm the crowd with funky house bops and sparkly energy.

The amount of women and non-binary talent on display across the festival, both local and international, was cheering to see. Other impressive Detroit acts included Lauren Flax, playing a jacking acid set on the Waterfront stage, Loren serving house heaters on the main stage, Ladymonixx rocking the Pyramid stage (always yes to Armand van Helden classics) and Beige treating the Stargate stage to a two-hour set, kicking off with spacey electro. “There has been some really noticeable effort put into booking more musically and demographically diverse local acts for the festival,” says Beige, who played Movement for the second time in a row this year. “It’s really exciting to see local favourites and up-and-comers from all different corners getting their flowers, and I think it’s been a motivating factor for the “underground” here to actually attend the festival, and not just afterparties.”

(The afterparties, by the way, are some of the best in the world. I was only able to attend a handful, including the raucous Club Toilet, joyful D-Life at Motor City Wine, Yes! at Marble Bar, and The Bunker at the Tangent Gallery, as part of Interdimensional Transmissions’ essential weekend-long Return to the Source party, albeit sadly not in time for Beige’s B2B with Octo Octa. All were fabulous).

Beige’s observation is apt though — the increasingly interesting programming at Movement does feel like it’s attracting more diverse crowds, including those who might deem the festival “too commercial” compared to the offsite, more niche parties. (Personally, I think it’s kinda refreshing to not be surrounded by uniformly “cool” people at the event — at Movement the EDC ravers, break dancers, daggy Dads, goths, business techno bros and local elders coexist in a fun, unpretentious melting pot).

But whether they were commercial or underground, big or small, all artists I spoke to deemed Movement their most nerve-wracking gig of the week. It’s an honour to be given such a large platform at the fulcrum of the weekend’s activities, and the chance to introduce their music to fresh ears.

Anecdotally, I heard from quite a few Uber drivers and local hospitality staff that the city seemed much less busy this year than last year, which surprised me as it didn’t feel that way either at the festival or at the after parties. And Paxahau say they had the same number of people through the Movement gates as in 2022. All tickets were $30 more expensive this year, however, something Paxahau say was necessary to offset production costs, which increased by 25%. At US$279, a final-tier general admission three-day ticket is comparable with or more reasonable than many other festivals, although it’s prohibitive for locals who once enjoyed Movement at greatly reduced prices. Today, 41% of Detroit residents live at or below the federal poverty line.

Read this next: How The Cost Of Living Crisis Is Impacting Festivals

Those who could afford tickets were likely impressed by the festival logistics. Free water could be found at the Underground Stage. It felt like there were more food options than last year (more drink options might’ve been nice though) and shorter queues for both food/drink and the toilets. There’s a great strip of market stalls between the main plaza and the Detroit stage selling everything from deodorant to Moodymann merch to official festival swag. Somehow, even with 30,000 other people attending, I didn’t have to wait to get in or out of the festival at any point. The sound was mostly excellent throughout the weekend, and especially during Underworld, who closed the festival’s huge main stage on Monday night.

It was the British duo’s first time playing in Detroit since 2002 and their 90-minute set was a masterclass: a flawlessly programmed run of 10 beloved tracks given plenty of room to build and breathe. ('Two Months Off' into 'Dark and Long (Dark Train)” live might’ve been the ecstatic pinnacle of all my years of gig-going). Grooving and jolting all over the stage like a flailing tube man, 66-year-old Karl Hyde could’ve been mistaken for a teenager. And the smiles and embraces he shared with synth-master Rick Smith throughout gave the impression the show was just as special for them as it was for the enthralled crowd.

The festival couldn’t have ended on a higher note. It’s a hell of an operation to pull off, but Paxahau refine their process year on year and that effort was really felt this year. They honour Detroit’s roots while attracting the biggest names in electronic music to produce an event that is profitable and sustainable. It’s deceptively tricky to do, but the festival is a model for how other cities might respectfully celebrate both local and international acts in a meaningful way.

Movement is a pilgrimage every die-hard electronic music fan should make at least once, as much for the music as to absorb the resilience and pride Detroiters rightfully exude. After their city was ravaged in the ‘60s by deindustrialisation, depopulation and racist housing and employment policies, the pioneers of the ‘80s built techno — today an industry worth billions — from nothing. Movement is preserving that history.

Annabel Ross is a freelance writer, follow her on Twitter