Features

Features

The unsung Black women pioneers of house music

Jaguar talks to the Black women who laid the foundations for the house music scene as we know it today

Giving a voice to the marginalised is vital and representation is key in developing a more equal and just world. I try to push this in everything I do: with my BBC Radio 1 shows to the brands I work with and the music I play in my DJ sets.

I also understand the importance of role models. The individuals who inspire a new generation to follow in and transcend their footsteps. But when I look back at dance music history, I am struck by the blocked narratives of our uncredited pioneers, many of who are women of colour, and queer women. Their contributions were and are vital to creating the scene we have today, yet their praises go unsung.

Dance music’s foundations of inclusivity and solidarity resonate with the world now more than ever, but as an industry, it falls short. It’s no secret that the intimate world first built by LGBTQ+ communities and people of colour is now begrudgingly and overwhelmingly white, male and middle class, as are the inner workings of the music industry. As an advocate of DJs and producers who are underserved by our industry, I always do my best to bring my peers upwards and create opportunities for them. The shift in dialogue in 2020 feels optimistic, as we’re making space for everyone to come through the door and be praised for their talent, from rising star Anz, to the formidable SHERELLE, to Honey Dijon’s unknockable top-tier reign.

We know about electronic music’s forefathers and legends: Larry Levan, Frankie Knuckles, Marshall Jefferson, The Belleville Three, Paul Oakenfold, Danny Rampling, among others, because history (of dance music and beyond) is always told from a male perspective. But what about our foremothers? Who are they? What are their stories? And how do they fit into the narrative?

I spoke to dance music innovators Sharon White, Stacey ‘Hotwaxx’ Hale, DJ Paulette, Smokin Jo and Ultra Naté to find out their side of the story and switch up the narrative.

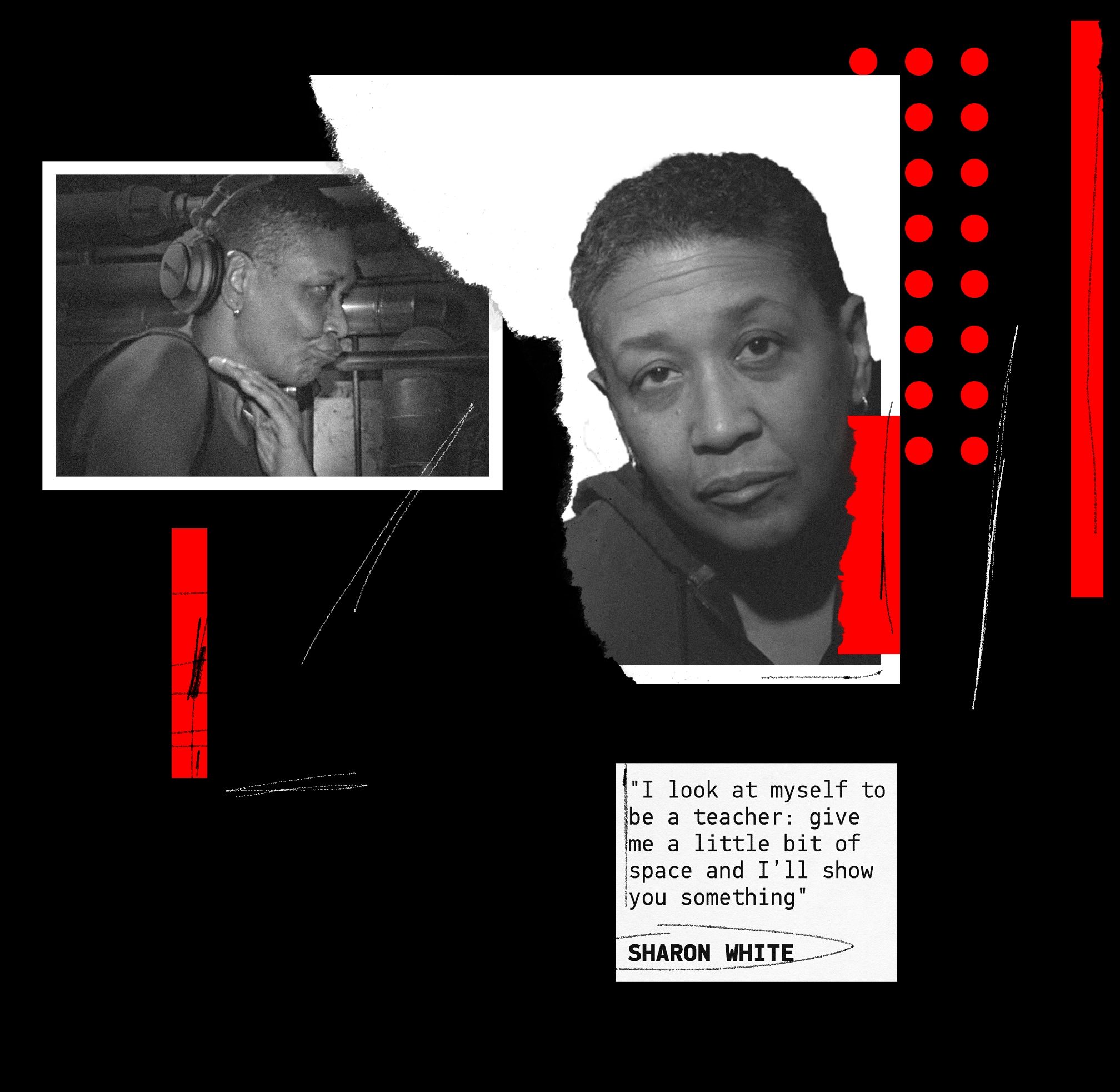

Sharon White is one of the architects of the house and disco scene. She cut her teeth in the 70s and 80s, playing around New York City’s Studio 54, Palladium, Sound Factory Bar, The Roxy, The Limelight, The Pavilion, and was the first woman to headline at The Saint and The Paradise Garage, as well as the first female Billboard reporter.

Name the women DJs who helped shape the early scene?

Let’s see: Michele Miruski, G Sky King (DJ Sky) – we all came up around the same time. I was a little earlier and I blazed a path. Also DJ Bexx, Donna Kornel, Patti Firrincili and Wendy Hunt.

What was it like DJing at The Saint and The Paradise Garage?

It was like going from a VW to a Maserati, you were like by the seat of your pants. That soundsystem was built like no other. To put it into perspective: the Giants’ football stadium had 20,000 watts, we had 28,000 watts. The DJ booth was all in the round, so in the monitors you heard what [the crowd] were hearing. It was just exquisite. At The Saint, a minimum night was 12 hours. I don’t know what we thought we were doing. The longest I played was 10pm until 7pm the next night – I was delirious! All I could do was lie on the floor and lock the door. It was like doing brain surgery. It’s just one person all the way through. It was insane!

On the other side of that coin, The Paradise Garage was built like the antithesis of The Saint. The Garage was all highs and mids, and The Saint was bottom and hard. So it was great to play both soundsystems and crowds. I maintained a lot of anonymity in The Garage, and if Larry wasn’t there, I used to get the call because I lived closest to it, and it was like, “Sha, what’re you doing tonight? Do you think you can open the room because Larry is nowhere to be found?” That was a common occurrence for Larry and I would play there Wednesday to Saturday in a row and I’d be called with half an hour’s notice. I’d go down and start the room up and then at 8 o’clock in the morning he’d come sliding in, fresh from wherever, with a smile on his face, and I’d say “Call your mom, and where the fuck have you been?!” He’d always come with gifts because he’d know attitudes would fly. Then the night would start all over again. You wouldn’t leave when Larry arrived, because that was when the party really started. So I’d be holding the room for 7 hours waiting, but that’s what we did, it was all love! It wasn’t competitive, everybody had something to offer, it was almost like a collective energy. And so many of those guys are not with us anymore. If those guys had got 10 more years, I don’t know what would have happened with music today.

The Saint was a predominately gay male, white club right? How was that experience for you, as a Black queer woman?

I came from the dancefloor, so [at first] a lot of people didn’t realise I was a DJ. I was one of the first people they offered the gig to. Then they changed management and the owner said “There’s no way I’m gunna have a woman at the helm at this club”. So I was hired then fired before I even walked into the booth! The resident Jim Burgess was leaving DJing to be an apprentice with Pavarotiti – this was a big event! The dude just decided he was going to leave at 8am in the morning. You can’t do that! The crowd were expecting the moon and the stars, and he just walked out. One of the managers Mark told me to go into the booth and play and I said “No, I’m not going to do that!’ Bearing in mind it was January, the coat check stopped, no one could get their coats, they were trapped and the music stopped.

I sent the guys back to my apartment to collect my records in different coloured bags. The track I started my set with was ‘Dance And Leave It All Behind You’. I played everything from A-Z and stopped at 1:45pm in the afternoon. People then said: “Who was that?’ and then I got booked again for the end of March because I saved the night.

You were a resident at lesbian club The Sahara. Tell us about that.

Sahara was one of a kind. I was a resident there for four years. The first floor was a bar, and a cabaret and a gallery, the second floor was a club with another bar. It was uptown, East Side New York. I would come in jeans and T-shirt, but people would dress up and very well-to-do people would go there, lesbians with money, and then also your regular crew. It was a mix of Black, white, Latina – everything. It was really the only game in town that was like a real club for women. After Sahara closed, people would rent a space and throw parties, but it really was one of a kind. It was all about dancing!

Did you find there were differences between playing in a female-only spaces like The Sahara compared to male clubs like The Saint?

[Playing for women] was really rough. Out of all the audiences, that audience was the hardest to please. They wanted to hear what they wanted to hear and nothing else. And I said, “Well, I’m not a jukebox”, they were very radio-orientated and they’d have so much attitude. I look at myself to be a teacher: give me a little bit of space and I’ll show you something, simple as that. There’s a reason why I’m standing here with two turntables and tonnes of records and they just would not loosen up. Trying to break them [free] of what they knew and what they wanted to hear and all the things that I was exposed to and wanted to hear... It was almost like the music was secondary and I wanted it to be primary. It was push and pull. The men wanted to hear things that were new and progressive, and the women wanted to hear what they were used to. There was nothing wrong with that at all, but I craved something other than that. It really was frustrating. I think this was because women’s comfort zone was radio and they worked in offices, where they listened to the hits, like the Hot 97 and so what they were comfortable with was what they knew, and they were uncomfortable with new material. I did my best, that’s all I can say!

Did The Saint ever try and run female-only nights?

No. It was like an unbroken rule. I think there were like 15 women in the beginning and I sponsored all of them to have memberships. The first person I sponsored was Wendy Hunt who was an amazing DJ from Boston. We were friends for over forty years, and she was [also] playing in the boys clubs.

What challenges, if any, did you face in your career for being gay, Black and female?

I didn’t really have any problems with [my sexuality], I was out in high school. It was just me. I didn’t really think about putting a label on my sexuality. The underground scene was very welcoming to everyone, and then the more commercial gay bars that were trendy, they wanted this, they didn’t want that. All that nonsense that they did at the door, like they did at Studio 54, which I was so opposed to, because a lot of people of colour got sectioned out.

When I was working at The Limelight, they really gave people of colour a hard way to go. One night Natalie Cole was coming to see me and she came in a limo and [the doormen] were like “No”. So I went down and took her and her friends up to the VIP lounge and went to the owner and I said: “This is Natalie Cole and your doorman wouldn’t let them in because he’s got an issue with their colour. You need to get him straight. And everything that they want, put it on my tab, thank you.”

Then going back to Studio 54, if you wanna get in, carry a record! Say it’s for the DJ and it always works! I would say to my friends, “Honey, grab a record and they’ll let you in” [Laughs].

That’s utterly ridiculous. What’s your advice to people of colour who might face these acts of racism?

It doesn’t make sense and it’s unfair. You have to call people on it. Some people don’t realise how wrong until they get called on it, and how prejudice [it is]. If you let them get away with it, they’re just gonna keep doing it. We’re still making baby steps after all these years, trying to get recognised just for being. I think people are starting to hear us now. All the [Black Lives Matter] demonstrations going on over the last few months all over the world...

What’s your take on it?

Well, I can’t believe that we’re still having the same conversations since I was a child. Is it 1959 again? I’m biracial and so your world is your microcosm when you’re a child, you don’t think “My mom’s this, my dad’s that”, so I couldn’t understand what that nonsense was all about. It was normal for me to embrace all different cultures. I couldn’t understand why people would call me names, and I would ask my Daddy what the N word meant? And he said “It’s your job to either educate them or let them bask in their stupidity. And don’t let anyone tell you that you’re not good enough”.

People of colour are being shot in the street. How many Black trans women have been killed? I’ve got a friend who has been missing for 3 weeks. We don’t know what to do. But it happens all the time and no one says anything because people say, “Who cares about Black trans women” and I say, “I do. So should you, it’s a human being”. It frustrates me. It’s all so simple. Treat people the way you want to be treated and it’ll be okay. Would you want to be shot or have someone put their knee across their neck? No. I hope something comes of [the movement] and it doesn’t just fade away.

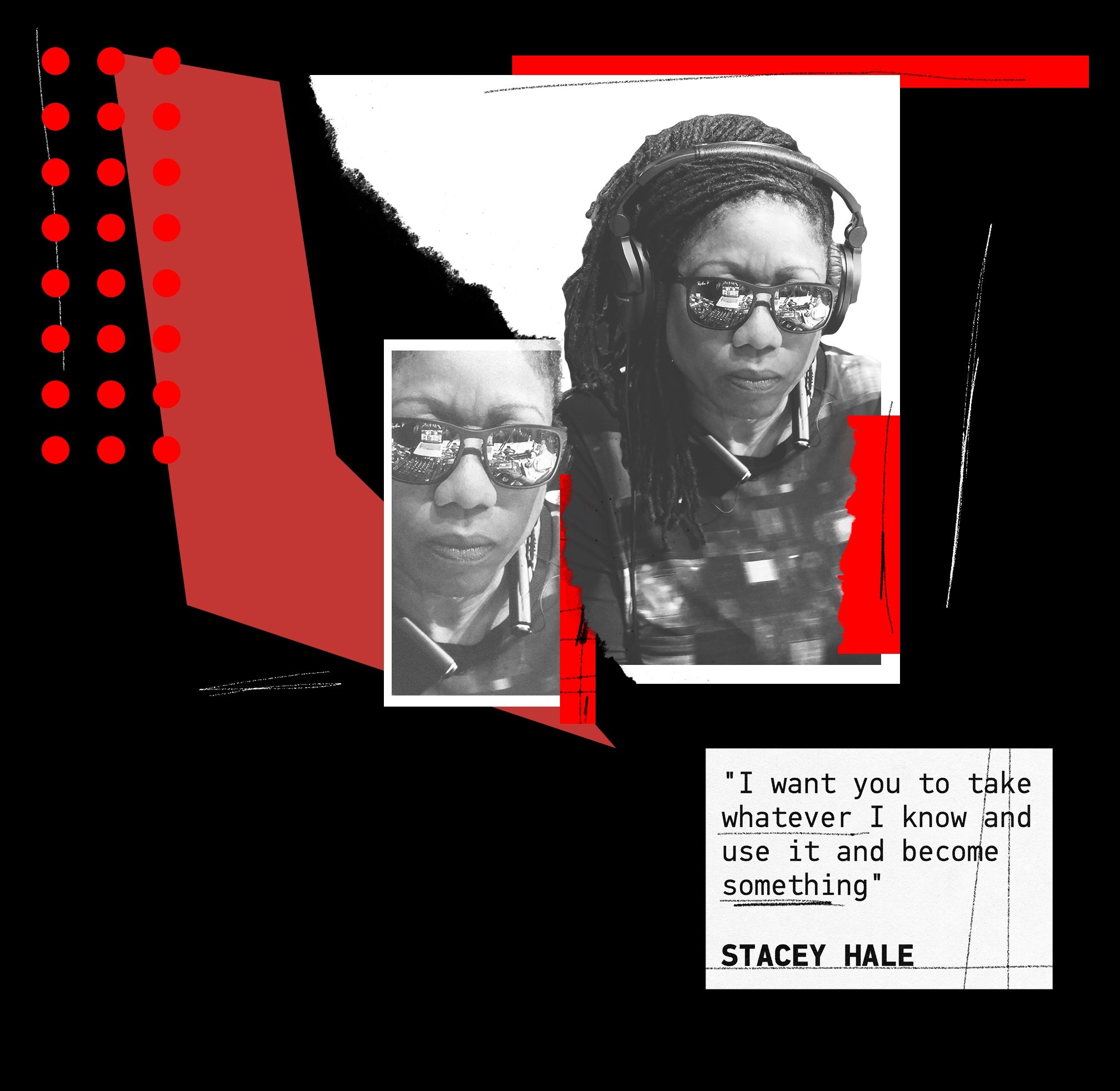

In the 80s, Detroit’s Stacey Hotwaxx Hale was a force driving forward the underground dance music scene, known as the Godmother of House. She played at Apollo, The Warehouse and Studio 54, pushing forward the ‘progressive’ sounds of the Motor City, leading to the birth of techno. Hale also mentors young people getting into music and founded the Lesbians of Color Support Network.

Tell us about those early days behind the decks?

I ran around with the guy DJs around here, and I asked Ken Collier if there was a woman that had stature like him, he said no and I told him I was gonna be that girl.

I was fortunate to be able to play at an all-female club, with approximately 800 women on a Saturday night, called

Club Hollywood and later Club Exclusive, in the early 80s. It was very exciting, however I was just coming out as a DJ, so I was scared to death. I would lock myself in the booth and was scared for people to talk to me. It was crazy! I wasn’t afraid of the people, I was just unsure of myself, and playing the music, you know, my confidence wasn’t up. I was doing well, but I didn’t know! I had plenty of records and was playing on early belt-drive turntables. That was how I got discovered by the city, and how they recruited me to play with Duncan Sound (a collective of DJs and promoters headed up by Ed Duncan). I had to audition, I remember being so scared that I wasn’t gonna get the job. When I did a mix, it was all guys, and one came running up to me like “Man, that’s what I’m talking about!” I got the job and then played for Duncan Sound, I was playing all around the city, then the next big job was a residence at The Lady. That was me and Jeff Mills aka The Wizard and myself Fridays. I would do the after work slot 4pm-8pm and he would come in and do 8pm-2am. We had to climb up the ladder in the closet to get to the DJ booth, and Derrick May lived across the street.

I would go to the male clubs to study, listen and watch. I’d go to Todds on Wednesdays and Club Heaven Saturdays after hours 2am-6am. I would go on my day off on Wednesdays. I’d go to Todds, and Club Heaven – I was always learning. I always wanted to play for the boys because the energy was through the room. I finally got my opportunity to play for the boys at Timesquare on a Sunday. The only reason I only got the gig was because Ken was too hungover. The promoter had plenty of men to choose from, but he knew that I could bring the heat, and he hired me. I introduced the kids to techno but I didn’t even know that’s what I was doing! I was playing stuff like Elevator ‘Up And Down’. That was techno, but I didn’t know it! I thought it was a hard house record, I don’t know. They would dance so much, the walls would sweat...

What challenges, did you face for being gay, Black and female in your life and career?

All of the above, getting paid, I’m sure the queer part has affected me to some degree, but it may be unknown to me. Being a woman, I was told that “If you don’t take off a record, you’ll be fired”. I don’t think they’d do that to a man. The record was Aretha ‘Jump To It’ and it was because they had not heard it before. I would get music before it comes out and so I would play it, if it’s good, I would be like “Oh my god this is great!’ That just blew my mind.

There were some incredible key players who are featured in this article alongside yourself who are queer women of colour who contributed massively to the scene but are never given the credit they deserve. Why do you think women are written out of it?

I have the answer! It’s a sad truth what’s happening – women have always been considered to be the weaker of the sex – so much to the point where in some countries today, they’re considered second citizens. In America it’s been just over a century that women have had the vote. So it’s popping the females in that category, and humanity is brainwashed to a degree that we are secondary when it comes to anything indicating power. Even women acknowledge the man first; that is conditioning.

I don’t like to be referenced as a female who did that, other than just a person. I’m not real fond of [the term] ‘female DJ’. There’s no need, just put them on there, you don’t have to call out what their gender is. I’m real strict on that. The music is universal and has nothing to do with gender. But yes, being female, queer, and Black we have to fight harder and be stronger.

What are you doing to stay active in the scene?

I want to make people better who have passion. I want you to take whatever I know and use it and become something, because that’s the best thing I can do with my career. So I teach and show and pave a way. The next generation like yourself, you’re the ones coming up and doing stories and covering us.

It took Turtle Bugg from Resident Advisor to tell the story that I created the first Detroit Regional Music Conference here. There was no internet and pictures. I constantly have to kick and scream and that is how this came about. John 'Jammin' Collins created an art display of the history of music and what was done in Detroit. Why did he leave my stuff out and I had to make him put it in? I knew him very well and he had a picture of one of the magazines that we produced without telling the whole story of what was going on. He just left out that part of history. And because he was my friend, I can cuss him out to get it right. I made him change some of the stuff up there, but I had to make him do that, and make him put me in the hall of fame in the techno museum because it was all men. He’s not anti-women or anything, [but] it’s that mentality. I looked him dead in the eye and said: “Mother fucker I deserve to be in that, how can you even not?” It’s not even a question. I don’t have to say anything. So I had to fight to get my picture and story in the museum, [alongside] Derrick May etc, I had to fight to do that. But either I fight or let it disappear.

People of colour are hugely important in dance music’s history, but in 2020, it seems to be very white washed and a lot of younger people don’t even realise the scene’s Black roots. What will it take for people of colour to be able to reclaim the genres and get the recognition they deserve?

You’re doing it, by telling the stories from the people that know, instead of [just] what you read. I beg people to take advantage of me, I’m here to tell the stories! There are not many people here that have lived these things and are still in the business. To get the stories from the originals who still exist and are part of the creation, and you're getting the message from Sharon, whatever she tells you, it's true, because she was there. I was listening and watching.

I saw Larry Levan, I went to the Paradise Garage, I never had a chance to meet him but I can tell stories because I was there. I can talk about T Scott, because I was there. He taught me how to sample. It’s important for people who are queer to be able to say it. To know it and it’s the truth. Mojo has encouraged me to write a book, I still have yet to do it, but it’s kinda important that I do that, to tell that story, but it’s up to me. We’ve got to give them the history, because there was no Facebook, all that is so important. So I’m happy to be a part of this article and talk to you.

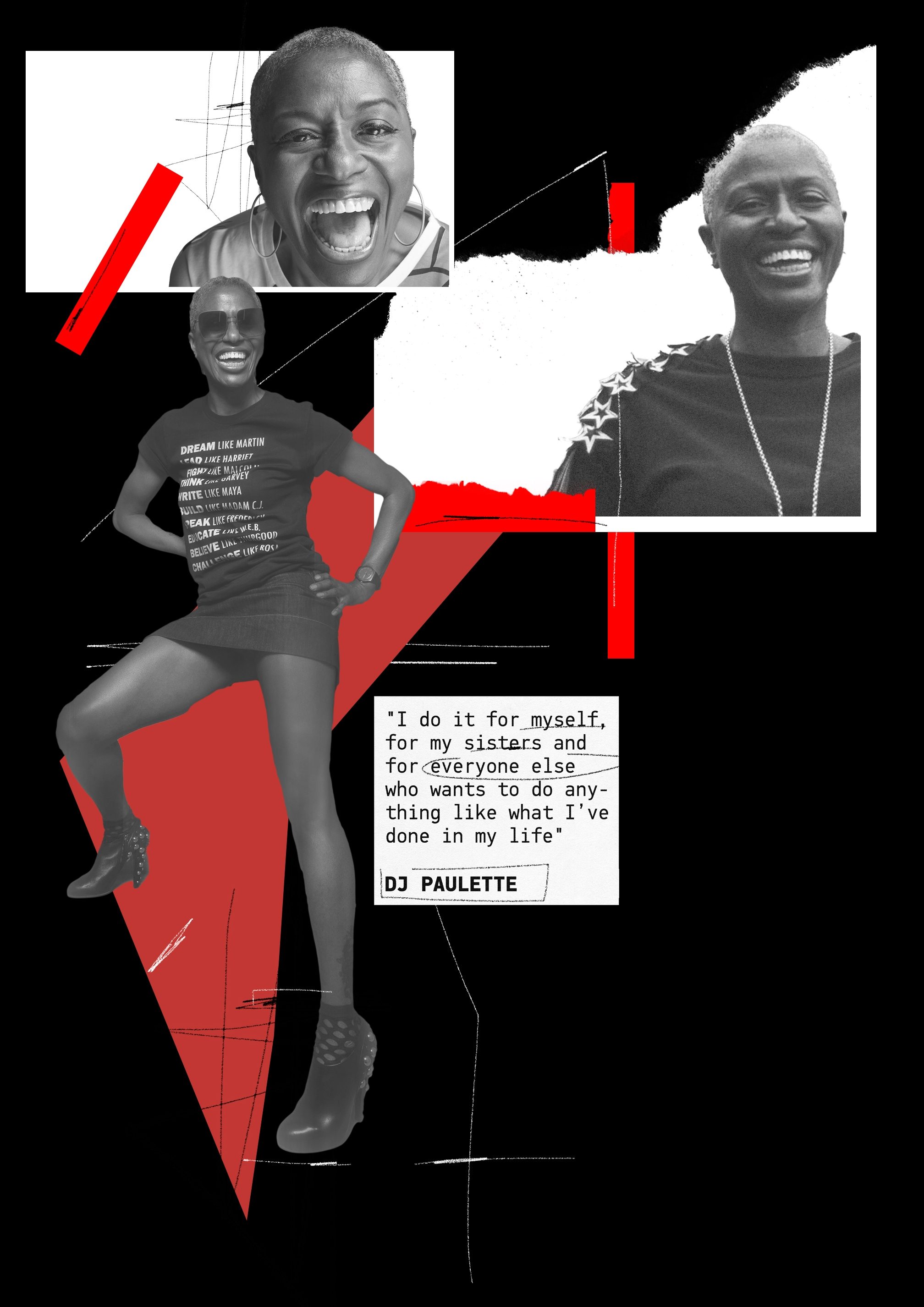

Over in the UK, during the 90s explosion of house music, Manchester was vital in cementing our ties with these new sounds coming from the US. The fame of The Haçienda which opened in 1982 until 1997 is widely known, along with its male residents, such as Jon Da Silva and Mike Pickering. Yet, unsurprisingly, the female pioneers are not documented in our history. DJ Paulette was a long-standing resident at Flesh at The Haçienda, and it wasn’t until recently where she has felt comfortable to use her voice and be unapologetically political about what was happening in her career, which you can hear in her track Sheroes.

In ‘Sheroes’ you shout out loads of women who helped build the scene, what’s the story behind this track?

I am very aware that women are being sidelined all the time. This shouldn’t be happening. I shouldn’t even have to write this track and say ‘we women are here’. The original version is 9 minutes long and it hurt to have to cut so many names out. It could have been half an hour long. I’ve become a lot more vocal and political the longer I’ve been in this career. I did an interview a couple of years ago and was asked “Why now?” Well, I’m 53, I’ve been DJing since 1992. I suppose when I started DJing, there still weren’t that many female DJs on the circuit, so I wasn’t comfortable to articulate these problems. I think with age, comes a sense of having nothing to lose. I’m not doing this for me anymore, I’m doing this for the people behind me. You’ve got to rip the plaster off otherwise this shit is never gonna heal and it’ll never be fixed.

Who inspired you when you were coming up in the 90s?

I can name the number of female and female queer DJs on two hands. Princess Julia gave me my first lesson in beat matching! And Mrs Wood – when I was playing at Heaven – she played the main floor. No other female DJ had that position because the main floor of Heaven was [someone] like John Digweed, and she used to pack it out! You had Mrs Wood on the main floor and then The Garage at Heaven on the second floor, where I used to guest, with Steven Sharp, Princess Julia and Rachel Auburn, who I think is a yoga teacher now. At that time I didn’t know any other female DJs and certainly on the LGBTQ+ scene, who were openly gay, the only one I knew who was a lesbian DJ was Kath McDermott. There’s also Philippa Jarman, Abs Ward, Paula and Tabs, from Manchester. Then in London Smokin Jo and Jo Mills, Angel From Venus in Nottingham, Clara Da Costa AKA Miss Bisto, Lisa Loud, Nancy Noise, Sarah HB on the soulful side, Marcia Carr, DJ Lottie, who was massive at the end of the 90s into the 2000s, Jill Thompson and Sonia who DJ’ed as Girls On Top who had a night called Damned Fine in Liverpool, and the big one - Sonique!

The sisterhood was strong but it’s a lot stronger now, it’s interesting to see how everyone really pulls together now, and all the different collectives. In the 90s, there weren’t many female collectives doing parties for themselves. But in terms of the big superclubs, women-only events were not happening. They just didn’t really do women-only parties, and when they were suggested it was just like the usual stereotypical comments from guys: “Are they all gonna be on their periods at the same time?” That was the attitude you got. Or you would be able to have a tiny little room but you wouldn’t be doing the big one. Whereas in 2020, Honey Dijon does four parties at big venues, I did the Penetrate one at Corsica Studios. The Blessed Madonna has her brand ‘We Still Believe’. You’ve got Nadine Artois’ and Pxssy Palace, and BBZ and Flesh In Tension in Leeds - I can name the female parties and collectives now!

How did the gay scene help and support you?

Gay culture is the foundation stone of everything I’ve done. Even now, I’ve always been looked after and nurtured, and helped, and promoted and supported by the gay scene. Quite a lot of the female DJs came through because they were working on the gay scene. I started at the Number 1 club in Manchester, it was a gay club. I did a few parties at The State and Oscars with Michael Barnes-Wynters and then I started to do Flesh in 92, then I went to the Zap in Brighton, Garage at Heaven and then the first big straight club was Ministry Of Sound. Flesh at The Haçienda made a point of saying this is a safe space for queers. It was very different in the the early 90s, everything was very heterosexual and aggy against queer culture. It wasn’t as accepted to be gay as it is now, [you couldn’t] walk down the street kissing your girlfriend, holding their hand, you were running a great risk of being properly accosted in the street if you did that. It was very separate when I started: you either played on the gay circuit or the straight scene. The two didn’t really mix.

Did you feel accepted in the LGBTQ+ scene as a bisexual woman? You have mentioned before about having imposter syndrome – did you feel you had something to prove by being bi?

I don’t think I’ll ever stop feeling like I’m an imposter! Christopher Biggins made a comment about bisexuals saying that we’re all frauds and should make a decision – that didn’t help. And in Black gay terms, it’s difficult being out and Black anyway, which ever way you swing. It’s still a taboo subject. I don’t really talk about it with my family - it’s so much easier with some members of my family than others. I have always found that being bisexual puts me on the intersection of everything. So I’m too gay to be straight, and too straight to be gay. I’m kind of on the outside of everything, but it’s just that feeling like, “She’s not really one of us”. I’ve never ever felt 100 per cent accepted in one camp or the other.

When I started playing at Flesh, I worked with a friend of mine, Adele, she was an out lesbian and it almost felt like we’d got it off the back of Adele being a lesbian. We hosted the Pussy Parlour together for the first few months but Adele never actually DJ’ed. We got caught and we nearly got fired. They said, ‘Well, we don’t know if you can continue with us because you’re not even gay,” and I said, “But I am, I’m bi” and they said: “Well that doesn’t count”. I really had to argue the toss. They gave me a chance and I was there for four years. It was that single event which has made me always feel like I don’t fit in, because they actually physically said to me that being bisxual didn’t count. In 1992, it really didn’t. So that set the tone for how out I was personally. I’ve been through a lot of therapy, and I’ve said, “I’m bisexual” and I’ve had at least had three therapists tell me i’m not… which also doesn’t help!

Then fast forward to 2001, I did an interview with Time Out for Patrick Lilley’s night at Turnmills, called One Nation Under A Groove. This was the first time I had a proper, steady girlfriend, and it came up in the interview, but I said “this is off the record, because my family don’t even know” and it ended up as the headline of the article: ‘DJ Paulette comes out’. I was just like, “fucking hell”. It was such a shock to my friends and it just caused a bit of an issue for me with work for at least six months. It really rocked the boat. It caused such a problem for me and that just sent me back into the closet for years. The relationship I was having would have lasted a lot longer if that hadn’t happened.

You’ve been vocal about changing the narrative of dance music. How do you feel your narrative has been erased?

Look at Peter Hook’s book, The Haçienda: How To Not Run A Club. I love Peter, he’s a really nice guy but in his book, when he made a point of detailing all the parties that ran through The Haçienda, and he was meticulous in doing it, and every time he mentioned Flesh he mentioned somebody that did not play in my room but did not mention me. I have four years of flyers and my name’s on every single one of them. I hosted that room. And to see that history accepted and repeated as fact, from such a revered book and a bible, really stings; this is how it happens! They just don’t tell the whole story. Somewhere along the line, between writing a book, and publishing a book, all that information comes out or it’s just not included. I’m not saying it was malicious, but it’s never been corrected. And people do refer back to that book for their stories and their research. Similarly, in Javi Senz’s Manchester Keeps On Dancing the film about The Haçienda released in 2017, they interviewed Laurent Garnier and Krysko, yet for the female part of the story they interviewed two DJs who weren’t even born when it was open and who never even played there. There was myself and Kath McDemott, we were the only two women who had a regular residency and our names were on all the flyers for Flesh, so either they just don’t want to tell the gay story or the female gay story, or even just the female story… Possibly with the Peter Hook story, he just didn’t want to tell that side of it.

Surely that’s just bad journalism?

That’s correct! A lot of the history of clubs is that they forget to talk about the women, or the gays. Or if they’re telling the gay side of it, they forget to talk about the lesbians. Of course you have to have a central point about your book, but you have to be accurate! You have to tell the truth and say who was there. You can’t just rub people’s names out.

I started to write a book and my trusted reader (an ex-Editor of a famous style magazine and features writer for broadsheets) told me that my life wasn’t that interesting really. He is white, heterosexual, upper middle classed and Oxford educated. He was reading my life from his level of entitlement and privilege so maybe it’s not to him. I am a Black, female, bisexual, who was born in North Manchester in 1966, and I have gone through various decades of history which are fucking flashpoints for Black British history. Just being Black before I’m anything at all, makes my story way different to his. So maybe now I could have more of a point of telling that story because there aren’t really that many Black, queer DJs. And there was no precedent.

What advice would you give to up-and-coming queer women of colour who are trying break through, and find where they fit in into this scene?

I read a phrase yesterday which said: “Believe in something even if it means sacrificing everything.” When I came back from Ibiza, I knew I’d have to stand up for myself. I’ve gone so many years waiting for people to correct things, listen to me and give me more than a crumb off the table. And then I thought, you know what? Fuck this. No one is gonna do that, I have got nothing to lose. I have to do it, and I do it for myself, for my sisters and for everyone else who wants to do anything like what I’ve done in my life. My hope is that if a tiny little word that I’ve said sows a seed in somebody important’s head that makes them change it, that makes it easier for people, then thank you fucking Jesus. It’s been worth it. I haven’t done this job for 30 odd years to not help people and to not make it easier for other people to come through. If you want success - get representation, and have someone beating your drum in your corner, network and get to know people. There’s a lot more of a sense of a community and collective spirit then there ever was, and that is what keeps me going.

There are loads of LGBTQ+ women who are smashing it now: the Meat Free collective in Manchester are flying the techno flag high. Bonzai Bonner and the Shoot Your Shot and Weirdo Warehouse parties in Glasgow and around Scotland. She is an awesome DJ (one of the most listened to guest mixes I have broadcast), she is a fierce lesbian and a fervent LGBTQ+ advocate.

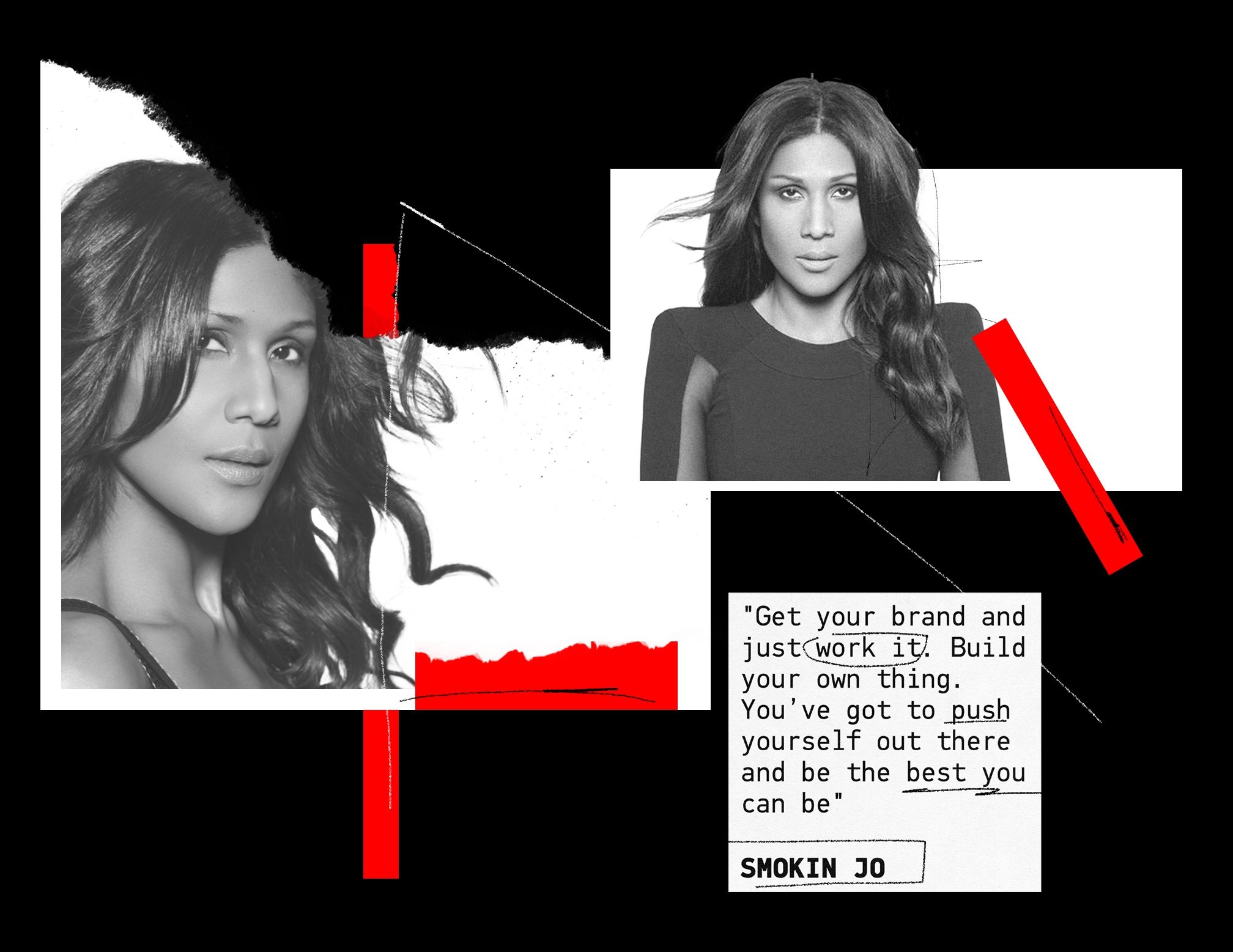

Another UK DJ who changed the face of electronic music with her cutting edge was Smokin Jo. She was one of the most prolific DJs coming through in the 90s and 00s, as a resident at LGBTQ+ club night Trade at Turnmills, Space in Ibiza and to this day still is the only woman to be crowned DJ Mag’s DJ of the year, in 1992...

Which women were coming through around the same time as you?

When I first started I didn’t know of any. I was out at every club and that’s what made me want to do it, and I thought, “Actually, I’m not seeing any women up here”, and once I started I heard about Nancy Noise, Lisa Loud and DJ Rap. That’s all I knew about. I don’t even know how many Black women are behind the decks. I don’t know many at all. [It could be that] we’re not just getting the press or we’re just not doing it because we don’t feel included.

So you were around loads of guys and you didn’t have any women to connect to and look up to in that way?

Not at all. It was really nerve-wracking. When I started, it was horrible. Men would just come round the decks and just look at you and they wanted you to be shit or make a mistake. So you’d find there would be like 30 guys looking at you and not dancing, and you had to be really good, so I knew I had to get my shit together. I had a shaved head at that point, and because of my name as well, some people didn’t know I was female, and that helped me in a way because they didn’t pre-judge. But once they found out they were like, “Oh she’s alright for a bird”. It was a funny old time, but I was determined to just do it, ya know?

Did you feel you had to smash every single gig because you were a girl?

Yeah, you could not in any way shape or form be shit because they were gonna rip you to shreds and they already assumed you’d be crap anyway. It’s fine for me, I like pressure. I was saying to another female DJ friend of mine that it’s generally women who are strong, bolshy and pushy characters [who DJ]. If you’re very femme and a bit shy it’s gonna be hard for you to get on as you’ve got to compete with these guys whose egos are huge.

How did the gay scene support and shape you as a DJ?

I did a few straight gigs which were cool and then once I started on the gay scene it went to a different level, because obviously with the gay scene they don’t give a toss whether you’re male, female, or whatever you are. They put me on this pedestal, I was one of their favourite DJs, I got so many gigs and was given so much attention that it was brought to the straight community. And the straight promoters, DJs and journalists used to come to the club. Trade was the only legal after-hours club in the whole of the country, so it was a big thing to go down there. That was a big platform for me. I’d only been working there then it was like wow, I’m getting gigs all over the country and being voted best DJ. Couldn’t have done it without the gay scene, 100 per cent.

What was it like behind the booth at Trade?

Mayhem! It was a moment in time that was just special. Everyone was there to get high and listen to good music (maybe shag as well) and it was about the music, so you had to bring the best tunes every week. I would spend a fortune on music every week. All the other DJs were amazing and I learnt a lot from them. At that time people didn’t come in the booth, now it’s the fashion to be behind the decks, with the DJ and dancing – it wasn’t then. Everyone was on that dancefloor, so you could really concentrate. It was electric, the whole club and the vibe, the energy – I don’t think I’ll ever have that again, that moment. I definitely cut my teeth in that club.

Because Trade went for so long, a lot of people only remember the hard house, but at the beginning it was me, Malcom Duffy, Trevor Rockcliffe, Daz Saund and that was the line-up. I think the fact that we were a real mix of heritages the music played was more soulful but it was still techno.

In 2020 we have lots of female and queer parties and collectives for women like Pussy Palace, Meat Free, BBZ, Femme Fraiche, Sistren, No Shade collective… What was your experience of the female scene back then, was there one?

At that point no, I mean there probably was, but you just didn’t hear of them. The one I remember was Kitty Lips, and that was run by DJs Queen Maxinne and Vicky Red, that was the only thing to be honest. It was decent music and females having a great time. Now, you’re so spoilt. When I played Femme Fraiche, I was like, “WOW, I wish we had this when I was around!” It was wicked.

I think the lesbian scene back in the day was very tame. Actually that’s a lie, you had the massive things like Venus Rising which were more sex/fun-lead, it wasn’t about the music, and it was just a different time where women weren’t really out and dressed up, and it was a different energy. I think now you’ve got so many role models, you’ve got different vibes, now it’s acceptable to be a DJ, it’s easier to get into it, so you’ve got these little communities popping up at different clubs. I think it’s amazing! I think it was probably quite daunting and it was like, “How do we even start this” and getting women down. I actually did a gay night for a bit and it was really hard to get women out the door. Women seemed to like to stay in more back then.

Were there any challenges you faced in your career?

Yeah, definitely, it was difficult, most of the time I was travelling alone. It was only when I started DJing with other DJs on these tours that I realised: “Wow, it’s so different for them”. I mean, the treatment they would get and the energy around them [was different]. It was mainly male promoters, and men that run the clubs so you’re completely surrounded by men the whole time, and as a Black woman especially going to Eastern Europe and Russia, it was pretty hideous to be honest. I’d get to the airport, all my bags were being searched, the attitude was stinky, I would never see another Black face. You felt very uncomfortable walking around the streets and I’d phone my friends and they’d be like, “Oh just go for a walk” and I’m like, “I ain’t going for a walk”. You don't realise but you can go for a walk anywhere in the world as a white male, but for me it was often very scary, I am not going out on the streets. I did once in Russia and I came back within about five minutes, because the looks I was getting were horrendous. Once I was in the club it was fine. But you’re definitely this kind of exotic thing. They don’t know how to relate to you and treat you. You have to be thick skinned, just get on with it, because you’re travelling to different countries, you’re on your own, sometimes there’s no one there to pick you up, they’ve forgotten to get you, and you’re in this airport and it’s really nerve-wracking. I keep saying to myself, “why didn’t I get someone to go with me?” Now, all these DJs have got tour managers and mates with them… I was on my own! So yeah, that was hard, and I know full well that I didn’t get paid as much and probably not offered as much. You know, when I was at my peak, I was a successful DJ and I know I wasn’t getting paid anywhere near what the male DJs were getting, and I'm sure it's the same now.

How have things changed for you in your journey as a DJ since then?

There’s so many more women which is great, and I really like it when women say, “You were my inspiration and I got into because of you,” and that is something I’m really proud and happy about. It’s not seen as a fad anymore and a lot of women are put really high up [on the line-up]. But I was booked for a festival last year and I counted all the DJs – 90 DJs – and there were seven women on that line-up. Again, it’s because men run these things and they book who they wanna book. It’s the way the world is.

You won DJ Of The Year in 1992 over Judge Jules and Carl Cox. Nearly two decades later you are still the only woman to win which is insane. What will it take for women to get the recognition they deserve?

I know, and I was so lucky to get that award. The same DJs were winning every year, and I had come into this realm and I had got so many votes and I think it was pretty close and they just thought you know what, we’ll put you forward. And that’s what it takes, it takes allies. But unfortunately, there doesn’t seem to be many Black, female or gay people working behind the scenes, which is very straight male, so they’re just going to keep on reporting the same things. We’ve got to place these people in these positions and we’ve got to put on more parties of our own and be part of the scene. Look at Glastonbury, which has done so well at bringing the whole gay community with Block9 to the festival where there was nothing before. Someone has got to open the door a little bit, as well as us pushing it down.

To be honest, it’s now about who’s got the best PR team behind them, isn’t it? I don’t know half of the DJs on the [DJ poll] line-ups now. It doesn’t make sense, but also the people who win play the big EDM stuff or big room techno or trance, that is always going to win. The gay or Black DJs are playing much more niche music, and it’s not played by everyone. I think they should change that poll to ‘best PR DJ’. But it’s not the best DJ is it...

With the Black Lives Matter movement, the world seems to be undergoing a long overdue global shift. How has this time been for you? As a successful Black woman in dance music, what changes do you want to see in our scene? How do you feel about everything happening and the changes we’re seeing?

I was really, really happy and surprised at seeing how many more white people on those marches, and that was something new and we hadn’t seen that. But also on the flip side, I don’t want it to be a fashion. Online I was horrified and I had to block so many people because then all this racism comes out, and you’re trying to educate people, but I got called a bitch and this kind of shit because I was trying to explain stuff. It’s that white fragility thing, isn’t it? I love that book by Robin DiAngelo, because you’ve got to try and keep the conversation going but people shut down. It got going for a few weeks, and I feel a little bit now that people get bored. We need, somehow, to keep the momentum going and I think people’s eyes have been opened.

What are your hopes and advice for future artists coming through?

The big mistake I did was that I didn’t take myself seriously enough. I just felt like I’ll kinda coast along. But it is a business, which is why you’ve got those guys doing so well at the top, because they’ve got their brand, their managers, their T-shirts and tracks. So, get your brand and just work it, build your own thing, maybe do a night, make your tracks and you’ve got to push yourself out there, rather than wait for someone to try and find you, and be the best you can be.

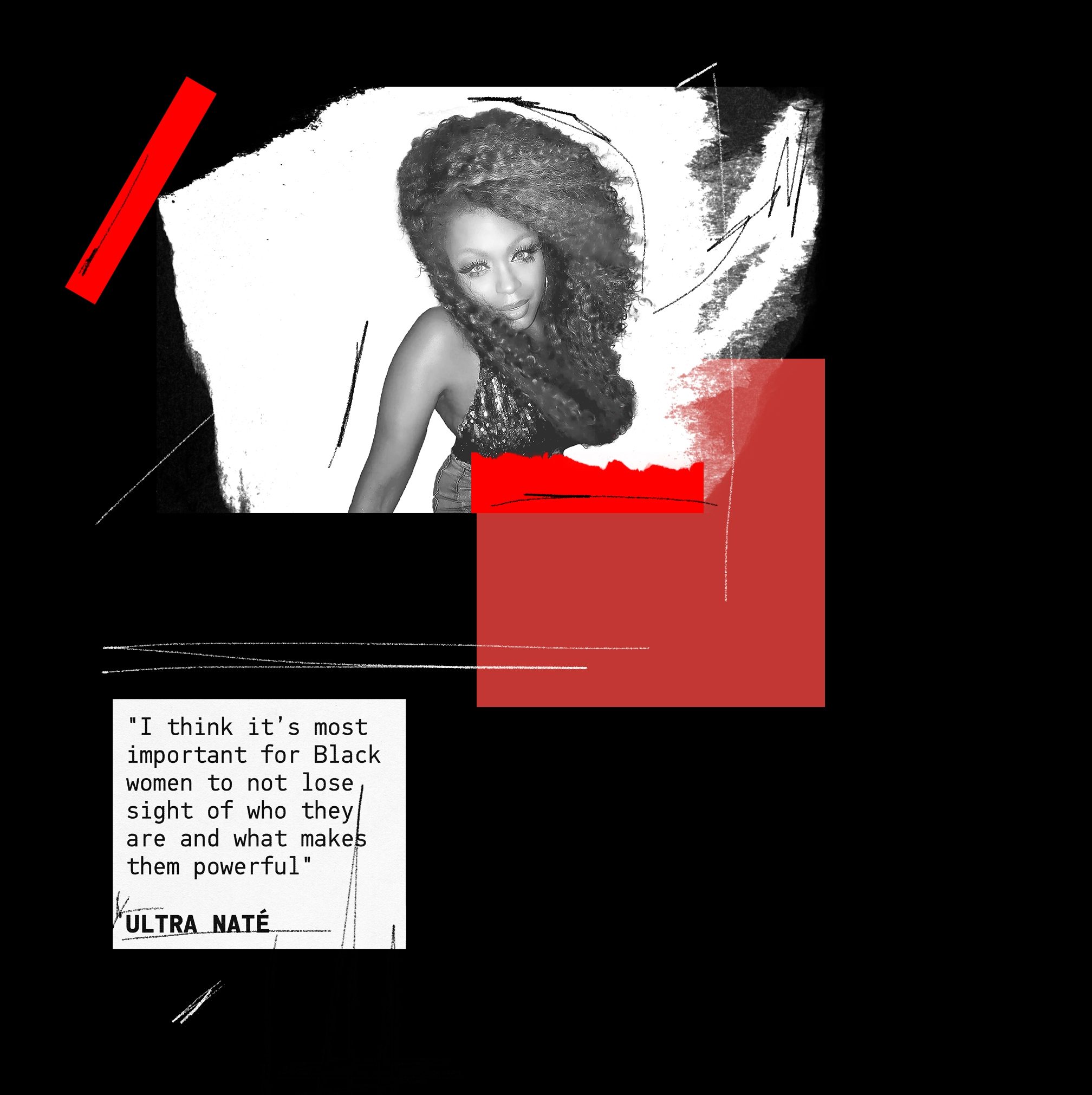

Musician Ultra Naté has been a stalwart in the house scene since she burst into the scene in 1989 and is behind classics such as ‘It’s Over Now’, ‘If You Could Read My Mind’ and the ultimate Pride anthem ‘Free’. Now, Naté is celebrating her 30th year in the industry as a singer, songwriter, record producer and DJ.

You are considered a queer icon! Tell us about your relationship with the LGBTQ+ scene...

My career started in the underground scene here in Baltimore with The Basement Boys. Sunday night was Basement Boys night at the club everyone frequented called Fantasy and it was understood as a gay night for the most part although it was supported by everyone. It was also the testing ground for a lot of The Boys’ new productions and the first time I ever performed live on stage. It was my friends in the queer community that really prepared me both visually and artistically for that performance which laid the groundwork for the next 30 years. From the groundbreaking Wigstock events every summer in NYC to endless Pride celebrations around the world through the years, the relationship has been one of mutual respect, love and appreciation.

Black artists are too often not credited for featuring on tracks, especially in dance music. I read about when Martha Wash was replaced in music videos for C&C Music Factory & Black Box by a different woman for 'marketing' reasons. How do you think people of colour, especially Black women are portrayed in dance music?

Black women have oftentimes been nameless, faceless and interchangeable additions to dance tracks over the years. As the genre became commercially viable, the music evolved away from the vocalist as the artist and became DJ/producer focused. However, there was still the desire for that element of soul to anchor a song to the dance floor coupled with less and less genuine artist development by labels. The opportunities for a lot of Black female artists was and still is relegated to “work for hire.”

What will it take for these vocalists to be credited?

The burden is on the artist to know what’s fair and to organize their business upfront. Unfortunately very few on the other side of the table will look out for you. It’s a business and everyone has to protect their own interests. The fortunate part is with technology information is now more readily available than ever before. You should at least know the basics. If people you want to work with are not willing to offer a fair deal then that tells you the real story.

What challenges did you face in your career for being a DJ who is a woman of colour? Did you feel you had to work harder/have more to prove?

I did and I still do feel the challenges. There were those who made judgments based on the fact that I was already a long time singer/songwriter before I started spinning. Some assumed it was contrived and that I didn’t play for real without actually ever hearing or seeing me play. And then there’s the issue of the really big festivals and events that are completely devoid of Black women DJs.

Any advice for Black, female artists making their way in the scene?

I think it’s most important for Black women to not lose sight of who they are and what makes them powerful. There is soul and confidence that comes through when they sing or when they play. It’s important to not dim your light or change your lane to appease others. It’s about observing and learning how to play the game while maintaining your integrity and authenticity.

Jaguar is a DJ, broadcaster and journalist and a regular contributor to Mixmag. Follow her on Twitter