Features

Features

Dance 'Til The Police Come: How oppressive policing has eroded rave culture

Mike Smaczylo traces a potted history of how draconian legislation and policing has harmed communities and crippled the spirit of rave

Following a year in which vast protests in support of Black Lives Matter highlighted the continued racial inequality in the UK’s policing policies, the Tory government’s Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill passed a third reading in Parliament last month.

Only months ago, the London Met Police violently disrupted a peaceful vigil for Sarah Everard, after one of its officers, Wayne Couzens, was charged with kidnapping and murdering the 33-year-old woman, which he has since admitted responsibility for.

These events brought to light racist neglect and misconduct in police handling of cases such as Blessing Olusegun, Nicole Smallman and Bibaa Henry.

The government’s response has felt confusing and callous, using the fraught moment to try and push through its draconian policing bill that human rights groups oppose.

Though it makes no mention of sexual assault or women’s safety, the bill gives the police unprecedented powers to control protests and criminalise protestors; extends prison sentences (which already disproportionately affect people of colour) despite a lack of evidence to suggest longer sentences reduce crime or increase public safety; and makes trespassing a criminal, rather than civil, offence. That is a first for this country and effectively criminalises the culture and lifestyle of Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities.

Read this next: Undercover cops is not the answer: nightclubs need to do more to protect women

Bizarrely, in the face of widespread criticism against the bill’s authoritarian measures, and the government’s continued failure to attend to the problem of male violence against women, Boris Johnson also announced in March that the government’s solution would be to deploy plain clothes police officers in nightclubs in order to “identify predatory and suspicious offenders”.

It’s a strange move. One of the points raised endlessly in recent months is the ubiquity of misogyny and sexual violence, occuring in offices, in parks, or while walking home, making No 10’s particular focus on clubs appear somewhat out of the blue. But it says something about the way in which clubs and live music spaces have again and again been the sites of conflict around freedom of speech and expression, the right to protest, police violence, ownership of space, and issues around race and gender.

Stonehenge Free Festival 1985

On a hot day in June 1985, a community of New Age travellers known as the Peace Convoy were stopped by road blocks and diverted into a broad bean field, on the way to the Stonehenge Free Festival, an annual music festival that had been running since 1974 and had hosted the likes of Hawkwind, Benjamin Zephaniah, Jimmy Page, Sugar Minott and Ozric Tentacles.

What followed would come to be known as the Battle of the Beanfield, and it resulted in [what was at the time] the biggest mass arrest in the UK since the Second World War, with 537 of the 600 Travellers taken into police custody.

Read this next: 25 parties that changed dance music forever

At the time Wiltshire police claimed that the Travellers were armed with chainsaws, hammers, petrol bombs and firearms, and that violence began when some of the travellers drove their cars through the blockade – later reports revealed this to be false.

A BBC documentary made in the following year shows that in fact the Battle of the Beanfield was no real battle at all, but rather an assault by an ideologically motivated police force on a group of non-conforming, but peaceful people and families.

As 1300 officers smashed up the Peace Convoy’s vehicles and homes – throwing rocks indiscriminately through windows, bludgeoning pregnant women with truncheons – the Earl of Cardigan, who owned the land, was so troubled by what he saw that he refused access to the police the following day, when they were hoping to finish the job.

The Battle of the Beanfield was the culmination of 20 years of rising tensions over free party culture and an already well established ideological clash over access to the land, notions of private property and trespass, and commercial interests. When the National Jazz and Blues Festival, which had already been a target for controversy and moralising amongst local residents in Windsor, made a dramatic switch in tone in 1967 by booking the likes of Cream, Donovan and Ten Years After, the Edenic romanticism of Albion’s hippie generation found its ideal outlet.

The following years saw an explosion in festival culture, with free party utopians and profiteering landowners jostling to supply the popular demand to ‘get back to the garden’. The bubble burst during the 1970 Isle of Wight festival, which had swelled in numbers from 10,000 in 1968 to an estimated 600,000 two years later. Situated on downland and surrounded by two layers of corrugated fence, the event dramatised the ideological clash that was brewing under the surface of the festival craze. Ticketless attendees looked on from the surrounding hillside while the festival played out within the metal confines, a scene which one attendee likened to a ‘psychedelic concentration camp’. The entrepreneurial promoters faced pressure from the police, the council and disgruntled locals on one side, and critics of enclosure and commodified access to the land on the other. Following the festival’s disastrous failure, Parliament passed an act banning unlicensed gatherings of more than 5000 on the Isle of Wight. But as Rob Young, the Electric Eden author, asks, “whose England, exactly, was this legislation intended to protect?”

During the Thatcher years – as privatisation, individualism, and the vilification of notions of community and society went into overdrive – free party people and other travelling communities based on utopian communitarian principles, along with gypsy and Romani people whose nomadic culture dates back to antiquity, were demonised and dehumanised by the state and media. A life without property became no life at all. To this day even overt prejudice towards GRT people goes unchallenged, and the same spirit of exclusion lurks behind the PCSC’s trespass law.

Babylon

Franco Rosso’s 1980 film, Babylon, stars Aswad’s Brinsley Forde as a young reggae DJ in South London, pursuing music in the face of racism from employers, neighbours, the National Front and the Metropolitan Police.

It’s soundtracked by UK dub mastermind and Linton Kwesi Johnson collaborator, Dennis Bovell. In fact the film is partly based on Bovell’s experience of being falsely imprisoned while involved with the reggae soundsystem, Sufferah’s HiFi.

In an interview with the Quietus, Bovell relates how he was working the Sufferah’s soundsystem one night in 1974, at the Carib club in Cricklewood Broadway, when a ‘fracas’ broke out with the police and Bovell was arrested and wrongfully accused of inciting violence against the police. An MC for one of the other soundsystems had apparently led anti-police chants and played the Junior Byles track, ‘Beat Down Babylon’.

Read this next: 28 photos of soundsystems through the ages

Bovell, however, was charged, tried twice at a cost of £500,000 to the taxpayer (the first trial ended with a hung jury), and jailed for six months as the apparent ringleader of the fray. It gives us a glimpse into the way the UK authorities have continually conflated civil unrest, political subversion, immorality, race and musical subcultures.

This conflation can be traced back to the 1910s, when Black American soldiers brought jazz to the UK, and Black music first met the particularly British brand of moral indignation that it has faced ever since. As Dave Haslam notes, in Life After Dark, the music was considered to be immoral and events were regularly shut down, a story that continues to find its parallels over 100 years later in the media hysteria and police suppression surrounding drill, and grime before it. This was also a period in which right-wing commentators began to connect Black immigrants with labour shortages, and employers used lower-paid Black labourers as leverage against unionised white workers, stoking tensions between the two groups.

In the ‘70s though, the particular scourge of Black communities in the London was Operation Swamp 81, a police initiative with the same unpleasant connotations of Donald Trump’s ‘drain the swamp’ catchphrase, in which plainclothes officers conducted stop-and-search operations in predominantly Black neighbourhoods. They were backed by the controversial ‘sus’ law, an archaic bit of legislation dredged up from the pre-Victorian Vagrancy Act of 1824, which allowed officers to arrest anyone appearing ‘suspicious'.

Up until the law was repealed following the Brixton uprising in 1981, it was used as a thinly veiled excuse to harass and wrongfully arrest young Black men in South London. A review led by Labour MP David Lammy in 2017 showed that while BAME people constitute 14% of the population of England and Wales, they make up 25% of the prison population. The review concluded that the justice system continues to discriminate against these groups, and needs reform. A justice overhaul announcement made in March, however, included new court orders making it ‘easier to stop and search those suspected of carrying a blade’.

Rave-olution

The Thatcherite fear of dangers to society such as loud music, anti-authoritarianism and communitarian social forms reached a climax with the heady days of rave. Unsurprisingly, a decade of rising inequality and atomistic politics failed to wipe out the troubling immorality and economic uselessness of youth culture (as Thatcher's Government perceived it), and instead only seemed to strengthen it.

In 1988, Thatcher was into her third term, only a couple of years away from being ousted by her own party. Early in the same year, the alien sounds of house and techno started to filter from the Black communities of Chicago and Detroit into the UK’s musical underground, filtered through headsy Northern breakdance crews and London DJs like Danny Rampling and Paul Oakenfold, who came across these records listening to the Balearic DJ Alfredo while on holiday in Ibiza the previous year.

Read this next: 30 years on: The Summer Of Love continues to inspire us

By the summer, acid house was everywhere, with soundsystems and raves popping up on unsuspecting landowners’ fields all over the country. Along with a hysterical anxiety over private property, whispers started to reach the tabloids about an alarming new drug called ‘Ecstasy’, which seemed to follow the music everywhere and induced the profoundly anti-Thatcherite effect of making ravers feel a blissed-up sense of communal consciousness.

In his book Energy Flash, Simon Reynolds writes, “generally speaking, Ecstasy seems to promote tolerance. One of the delights of the rave scene at its height was the way it allowed for mingling across lines of class, race and sexual preference.”

As well as returning to work with debilitating comedowns that would eat up two or three days of the week, young people started talking about universal unity, togetherness and ego death, flying in the face of the Prime Minister who once claimed “there’s no such thing as society”. The sort of ideals held by fringe groups like the Peace Convoy earlier in the decade had gone mainstream. The Second Summer of Love was here.

[Image: featured in the Sun, November 1988]

While the tabloids churned out anti-rave propaganda at a fever pitch, the police waged an ever-escalating war against rave promoters and partygoers, monitoring pirate radio stations, tapping telephones, and tracking promoters with helicopters.

Read this next: Tabloid coverage of the Summer of Love was the original fake news

According to the law at the time, the police were supposed to observe but not intervene in gatherings of more than 100 people, a measure intended to minimise the possibility of violence. This led to a cat-and-mouse game in which rave promoters attempted to outwit the police, using secret rave hotlines and clandestine marketing tactics to elude them for long enough to get the party started. In a documentary by the BBC, one promoter describes an occasion on which his crew sent a lorry the wrong way round the M25, and while the Met gave chase, sent the soundsystem in the opposite direction, towards the intended site, ensuring the party was in full flow by the time the police arrived.

But legislation soon began to catch up. In 1990, Tory MP Graham Bright introduced the Entertainments (Increased Penalty) Bill, known colloquially as ‘the acid house party bill’, raising the penalty for throwing an unlicensed party from a £2000 fine to £20,000 and a possible six month jail sentence.

This was instrumental in bringing dance music into clubs, where the music could be commercialised, rents and alcohol duties could be collected, and subversive behaviours could be monitored. It also brought the rave scene back under the logic of traditional patriarchal nightlife culture, in which parties are for boozing and going ‘on the pull’.

Simon Reynolds notes that, “one of the most radically novel and arguably subversive aspects of rave culture is precisely that it’s the first youth subculture that’s not based on the notion that sex is transgressive. Rejecting all that tired sixties rhetoric of sexual liberation, and recoiling from our sex-saturated pop culture, rave locates bliss in prepubescent childhood.”

By 1992, the Met’s Territorial Support Group, a specialist paramilitary-esque unit set up to secure the capitol from terrorism and disorder (though more often found decked up in riot gear at political demonstrations), had become something like a dedicated anti-rave squad. On April 19, they surrounded a Spiral Tribe rave going strong in an abandoned warehouse on Acton Lane in West London. After some time causing confusion around who could come in and who could leave, they broke through a wall with a JCB digger, and proceeded to smash up the equipment and assault the partygoers.

One Spiral Tribe member, years later, told the Guardian, “everyone who was there remembers exactly what happened. Being forced down onto muddy floors, being battered. It was a horrible experience.”

Read this next: Children of the original travelling soundsystem DJs are upholding their parents' legacy

After the historic rave at Castlemorton, attended by 20-40,000 people, 13 members of Spiral Tribe were arrested and charged with public order offences. Their trial became one of the longest and most expensive in UK history at that time, costing the taxpayer £4million. Despite best efforts by the police, all 13 were acquitted.

However, police pressure continued to mount on the free party scene at the same time as movements were made to extend legal licensing hours in clubs, with superclubs like Cream and Ministry of Sound able to thrive while underground DIY parties became all but extinct.

Section 63

The final nail itself was the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act of 1994, also known as Section 63, which gave the police powers to remove anyone from ‘a gathering on land in the open air of 100 or more persons (whether or not trespassers) at which amplified music is played during the night’.

The impact of this bill on UK music and culture reverberates through to today and speculations about how these might have developed had raves not been criminalised could fill books. It’s more pertinent to note here, though, the direct link between this law and the greater police powers over protest passed in the new bill. Raves and political demonstrations have been linked from the start, and perhaps most emphatically in the eyes of our neoliberal governments. The other key point is that the biggest impact has been felt by women and people of colour.

Read this next: Nightclubs aren't utopia for every Black raver

As we’ve already seen, it also forced nightlife inside commercial clubs. While these clubs often tend to reproduce the misogynistic, heteronormative culture of the outside world, raves and DIY events have often been a safe haven for queer and trans communities, and for women hoping to escape harassment and unwelcome male attention. But with the culture being squeezed into licensed venues to profit landlords and breweries, these sorts of spaces tend to be fleeting and are increasingly hard to find. The raver’s sense of community hangs on, frayed and dislodged, but just about intact.

Jesse Bernard notes in Esquire that racist door policies and dress codes at white-owned clubs, and the fear of harassment inside such venues, has created a long-standing link between ethnic minorities in Britain and unlicensed parties. The rave act opened the door to further police harassment and intrusion into private garden parties and street parties in majority-Black neighbourhoods, and license to xenophobic neighbours, itching to pick up the phone and shut down the fun.

Form 696

In fact, majority-Black events aren’t safe even in licensed venues. Grime and drill are big-money ventures these days, with the backing of major labels. But police interference keeps Black artists in a precarious zone.

Form 696, a controversial risk-assessment form for club venues was finally scrapped in 2017, after mounting pressure and years of criticism from high-profile rap and grime artists like Giggs, JME and P Money.

Red this next: Timberland and Giggs team up to celebrate the review of the 696 Form

The form specified that it applied to events that ‘predominantly feature DJs or MCs performing to a recorded backing track’, a specification that distinguishes grime, hip hop and drill artists from live bands. In 2009, the Met Police removed two questions pertaining to the ethnic make-up of the audience and the genre of music played at the event. By 2017 it was found that other forces, such as Leicestershire Police, had continued to include the scrapped questions about ethnicity, while a number of Black artists in London continued to insist that the contents of these forms were being used discriminatingly to cancel their shows.

P Money told the BBC: “It's been happening for so many years that now we kind of know, it's just our scene. They [the police] target grime a lot, they just blame a lot of things on grime… Why is it different? There's fights everywhere, there's situations everywhere at all types of shows, all types of things, whether it's punk, rock, hip hop, pop, whatever.”

While Form 696 has now been scrapped, the younger, more angry post-recession genre, UK drill, has seen a resurgence in media hysteria and that moral indignation jazz was met with a hundred years ago.

As other genres have before, drill trades in a picture of authenticity, mythologising the violence of inner city neighbourhoods. With its masked aesthetic, clandestine symbolism, and references to real-life gang clashes, drill has been quick to draw the attention of the police. Many MCs have reported having shows shut down because of police threats to revoke venues’ licenses, or had music videos removed from YouTube. Others, such as Rick Racks, have been banned from using words like ‘bando’ ‘connect’ and ‘trapping’: an astoundingly granular level of censorship. Lyrics and music videos have increasingly been used as evidence in court cases.

Digga D, who was sentenced to a year in prison in 2018, for conspiracy to commit violent disorder, returned to making music with a draconian set of parole obligations, including supplying police with lyrics within 24 hours of releasing new music, a ban on descriptions of gang violence, and limitations on public statements about his past.

Read this next: The sound of UK drill will turn a rave into a mosh pit

Beyond the bravado, drill speaks to some of the grimmest and most serious issues of post-austerity Britain, not only lifting the lid on the poverty and violence plaguing communities ravaged by welfare cuts, but in its own way providing a possible route out of the cycle of poverty and gang violence, for a lucky few artists that ‘make it’.

The hostile and heavy-handed response of the police shows again the incapacity of an institution built on enforcement to deal with the complex issues of today, as well as a worrying keenness to silence depictions of the continued effects of austerity and welfare cuts.

Club Closures and Gentrification

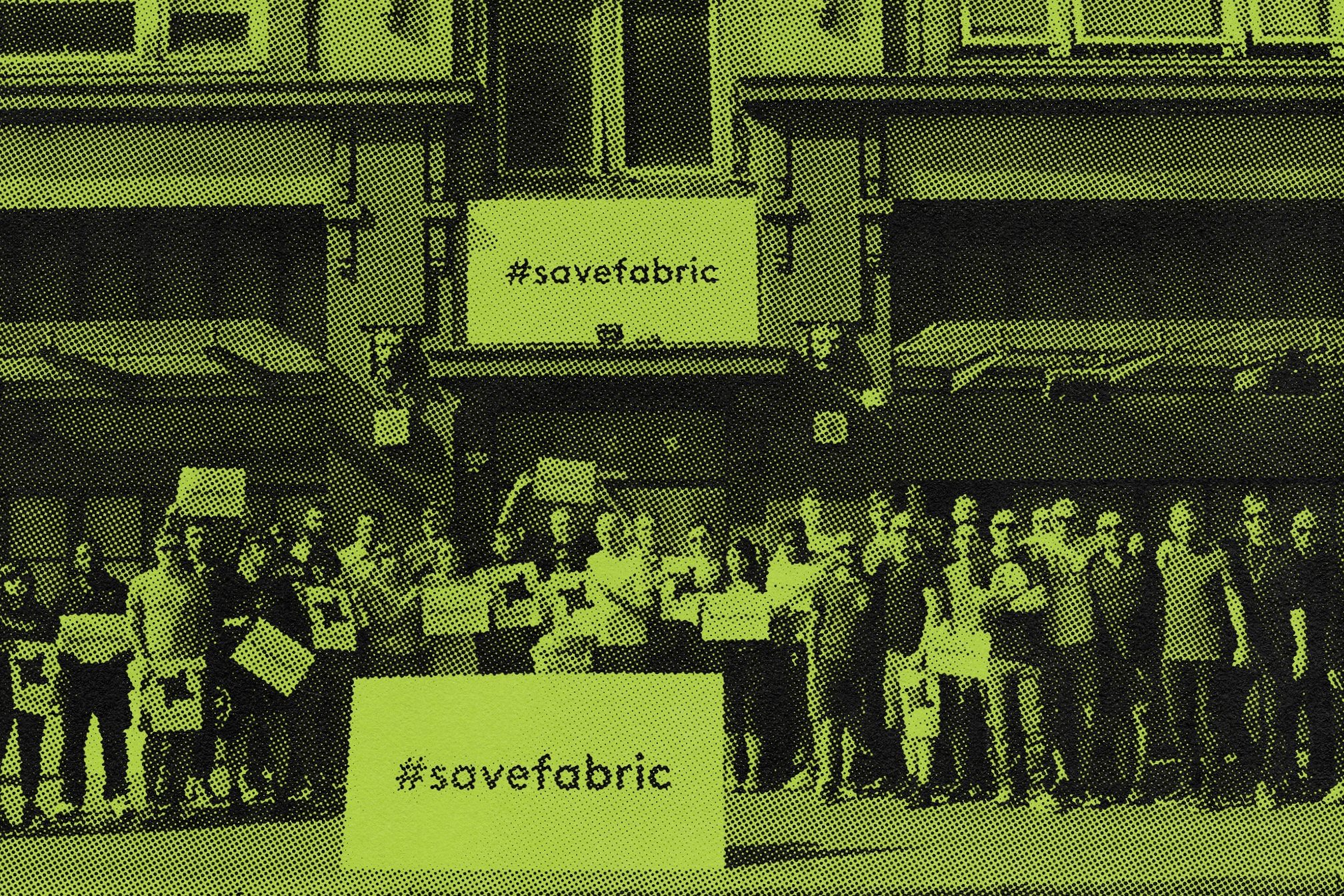

When fabric closed following the drug-related deaths of two party-goers in 2016, it took nothing short of a mass movement with a 150,000 signature petition, the backing of numerous high profile DJs, and the Mayor of London to reopen it.

The decision to close the club was made by Islington Council with the backing of the Met Police, after eight years in which more than half of London’s clubs had closed their doors for good.

The Trainspotting author, Irvine Welsh, called it “the beginning of the end of our cities as cultural centres, and indeed as entertainment centres in the traditional sense.”

According to Welsh, echoing widespread concerns among dance music fans and artists, “it’s all about property development. In the epoch of neoliberalism and corporate elites, entertainment is being privatised, and will increasingly take place within gated communities, owned and rented out by largely foreign investors.” The Scottish novelist may have had The Arches in mind, a Glasgow venue forced to close not long before, and swiftly replaced with a food market.

Read this next: The Arches in Glasgow is turning into a coffee shop and we're not happy about it

The closure came in spite of recommendations from drug safety groups, who argued that closure of venues like fabric, which are well-equipped and trained to deal with drug-related accidents, would take drug use out of the club and into streets and homes, where people can less easily get help. The closure of the Arches was followed by a spike of drug-related deaths in Glasgow.

Fabric was able to re-open due to vast public support and the backing of high-profile figures, and then only with stringent surveillance measures put into place. So too, Ministry of Sound before it, avoiding closure in 2013, following a four-year battle against a huge housing development that was intended to be built yards away. Both good-news stories for club culture, but also signs of a worrying division: on the one hand, a group of powerful clubs with political clout (another example being The Warehouse Project, owned by Manchester’s night mayor Sacha Lord, appointed by Mayor of Greater Manchester Andy Burnham in May 2017), and on the other, the vast majority of independent clubs and DIY party spaces that are far more susceptible to the encroaching tide of privatisation.

It was the sustained attack by the police and lawmakers on rave culture that pushed dance music into commercial clubs. We’ve already seen how this stifled alternative spaces in which the usual divisions and inequalities of British society were, at least in some cases, suspended. The commercial clubs, centred around alcohol sales, expensive ticketing and the logic of landlordism, tend to replicate heteronormativity, misogyny, and divisions along racial and class lines. Clubs have a big and serious problem with misogyny and sexual violence – that’s a fact, and it’s generally magnified by booze and the widespread emotional repression that still tends to characterise relationships in this country.

But to be clear: this is a reflection of the world outside. Having forced rave culture to move inside clubs, the Government’s new solution makes those clubs a scapegoat for a problem it refuses to accept as a societal one. Their proposal to send plainclothes police into clubs feels less like a consideration for women and more like one more attempt to tighten the grip on a culture that barely has a flicker of radicalism left in it.

Our culture has to change to make women in this country safe: this change has to start with legislation and with education. But the police have shown during the recent Kill The Bill protests, and time and time again before that as documented by organisations such as Netpol, that public safety isn’t their primary concern.

Mike Smaczylo is a writer, music supervisor, and DJ, follow him on Instagram