Cover stars

Cover stars

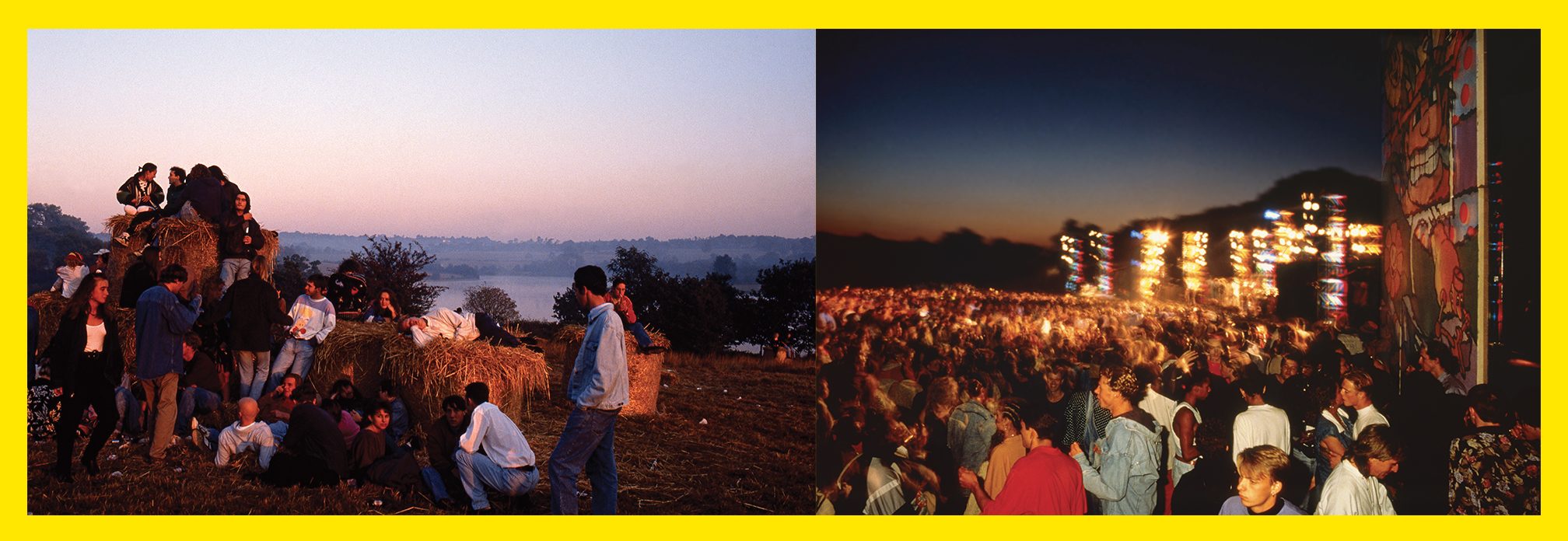

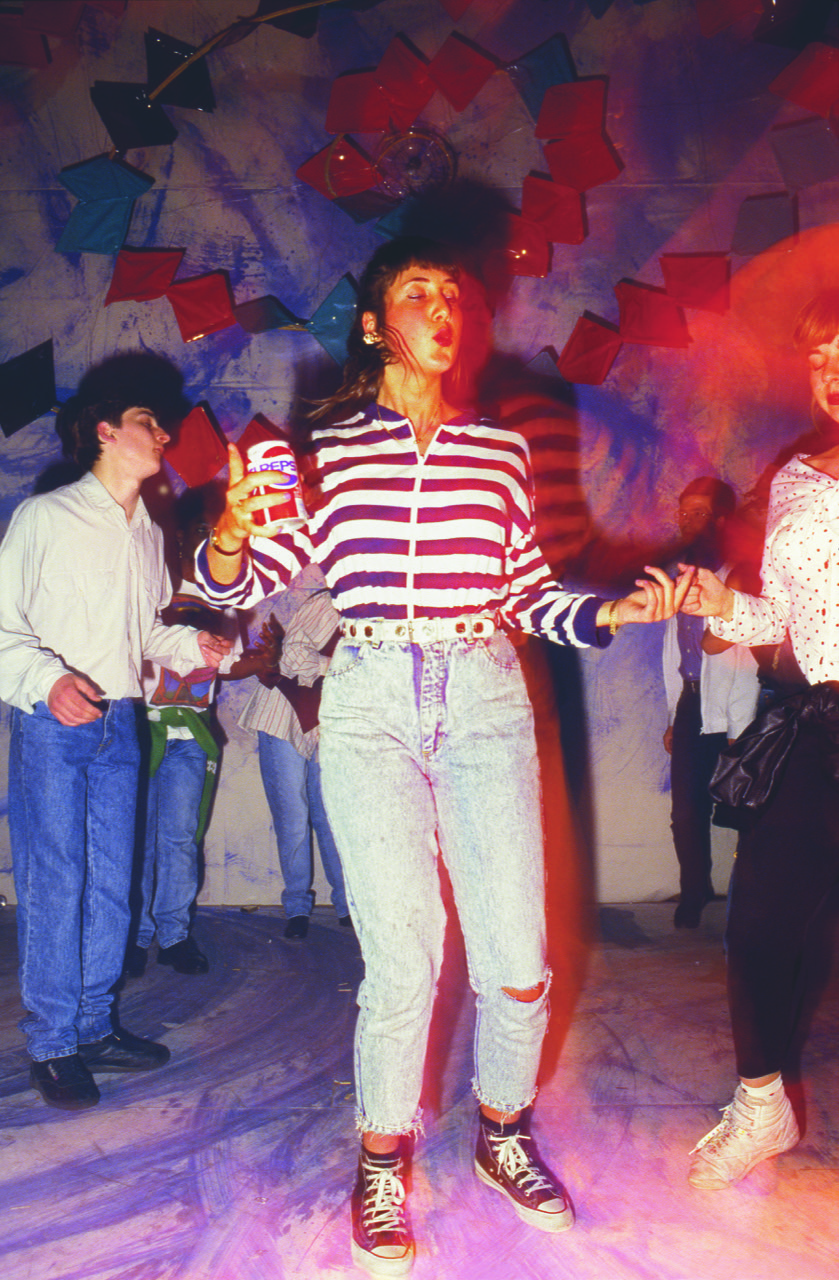

30 years on: The Summer Of Love continues to inspire us

A special celebration of one of the most important eras in dance music

In 1988 through 1989, the club culture that a few individuals had the previous year imported from the dancefloors of Ibiza spread like wildfire to the clubs, warehouses and fields of the UK and beyond, radiating outwards in an unstoppable supernova of love and creativity that changed fashion, design, clubbing, music and indeed the world, forever. This issue of Mixmag is a very special celebration of the 30-year anniversary of the second ‘Summer of Love’. Archive pictures and journalism from the era sit side-by-side with those clubs, festivals, artists and parties that carry that flame to this day, a specially commissioned fashion shoot features the brands and young designers who are most directly influenced by the starburst of freedom those years ignited, while Bill Brewster’s feature explores how the legacy of dance music’s Summer of Love continues to affect and inspire us, even now.

In 1988 a seismic change occurred in British society. It was caused not by a violent insurrection, demonstrations in Trafalgar Square or shadowy forces manipulating social media. The source of this bloodless revolution was a bunch of records from Chicago, Detroit and New York, a love drug called ecstasy and a load of potty youngsters doing the St Vitus Dance.

The hippie original may have been way back in ’67, but dance music’s Summer of Love was 30 years ago, an explosion whose shockwaves are still now rippling out across the world. It changed the fashion, the drugs, the clubs, the politics and the high times. The music of that period became known as acid house, but it’s a shorthand for wildly divergent sounds that range from funky pop records played by Alfredo in Amnesia to Detroit techno, Chicago house, New York garage and even hip hop. In 1988 this music combined with a powerful new narcotic to create arguably the most far-reaching and long lasting youth cult we’ve ever seen. It was the year that British youth discovered how to turn on, tune in and drop one.

Suddenly, all previous certainties melted away like a pill dissolving on the tongue. A new era was afoot. It was all about giving it a go and not giving a fuck. Gas fitters became DJs, aircraft personnel became record label owners, bank managers jacked it in to run clubs. Everyone was an impresario, everyone knew someone who’d made a tune. Qualifications? Fuck ’em. All you needed was the gift of the gab and a set of decks.

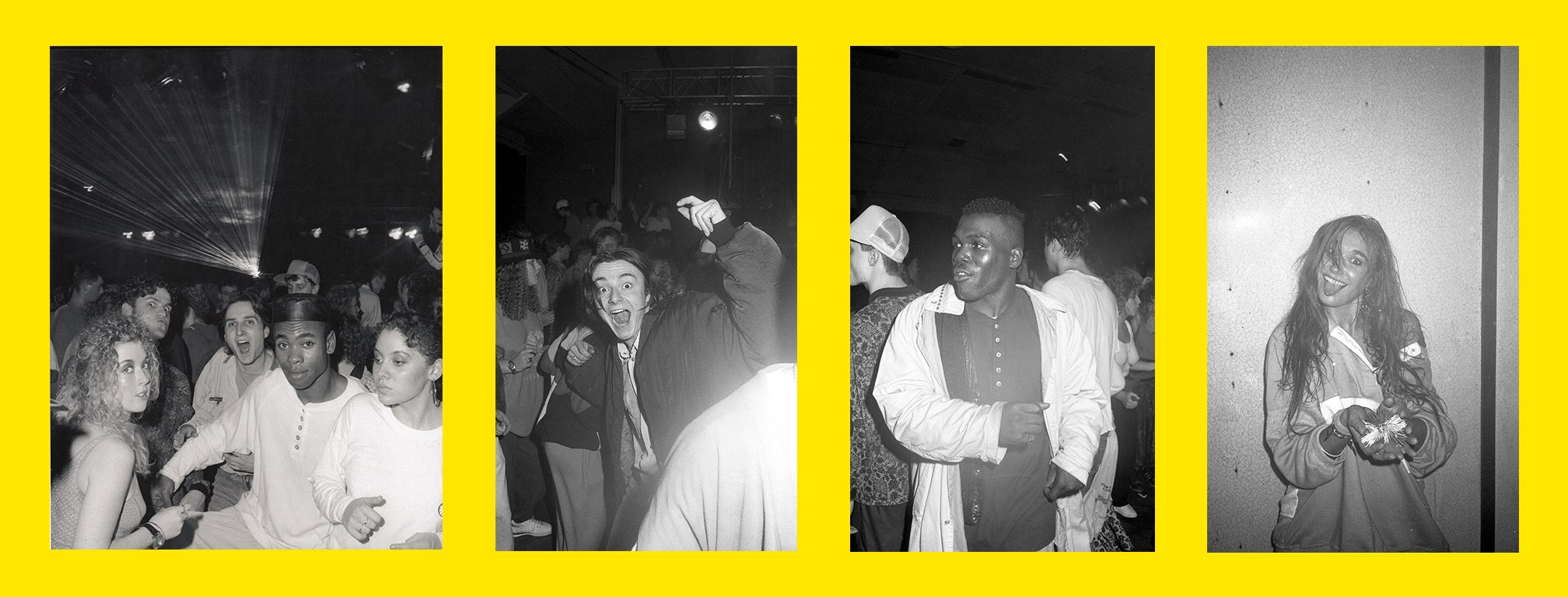

The Summer of Love not only changed how we danced and where, it altered our relationships, our interactions, and the way we saw the world. Peering through its foggy prism, suddenly we were no longer alone, but one giant collective of smiling, happy people. For a short time it was a national secret that only teenagers seemed to know about, while the police looked on puzzled, politicians observed fearfully and breweries met it with mounting panic. Eventually they colluded to bring in laws to try and contain it. But how do you contain a revolution?

THE CHANGE

In 1986, Nancy Turner (later DJ Nancy Noise) spent the whole summer in Ibiza. Sometime in June she discovered Amnesia and became obsessed with the music its resident DJs, Alfredo and Leo Mas, were playing. “They played the same music all the way through the summer,” she remembers. “It was like Balearic brainwashing! We left after the summer and literally all we spoke about was Amnesia. We were like lunatics.” The following year, Turner saved enough money to go again for the whole season, and went to Amnesia every night. During those languid summer months she bumped into friend Paul Oakenfold and his buddies Nicky Holloway, Johnny Walker and Danny Rampling, all equally blown away by the club and a new drug, ecstasy, that they’d sampled. When Oakenfold got back, having noted Nancy’s collection of Alfredo classics in her flat, he asked her to come and play at his new night, The Future. Opening in January 1988, it was the first time Turner had ever DJed.

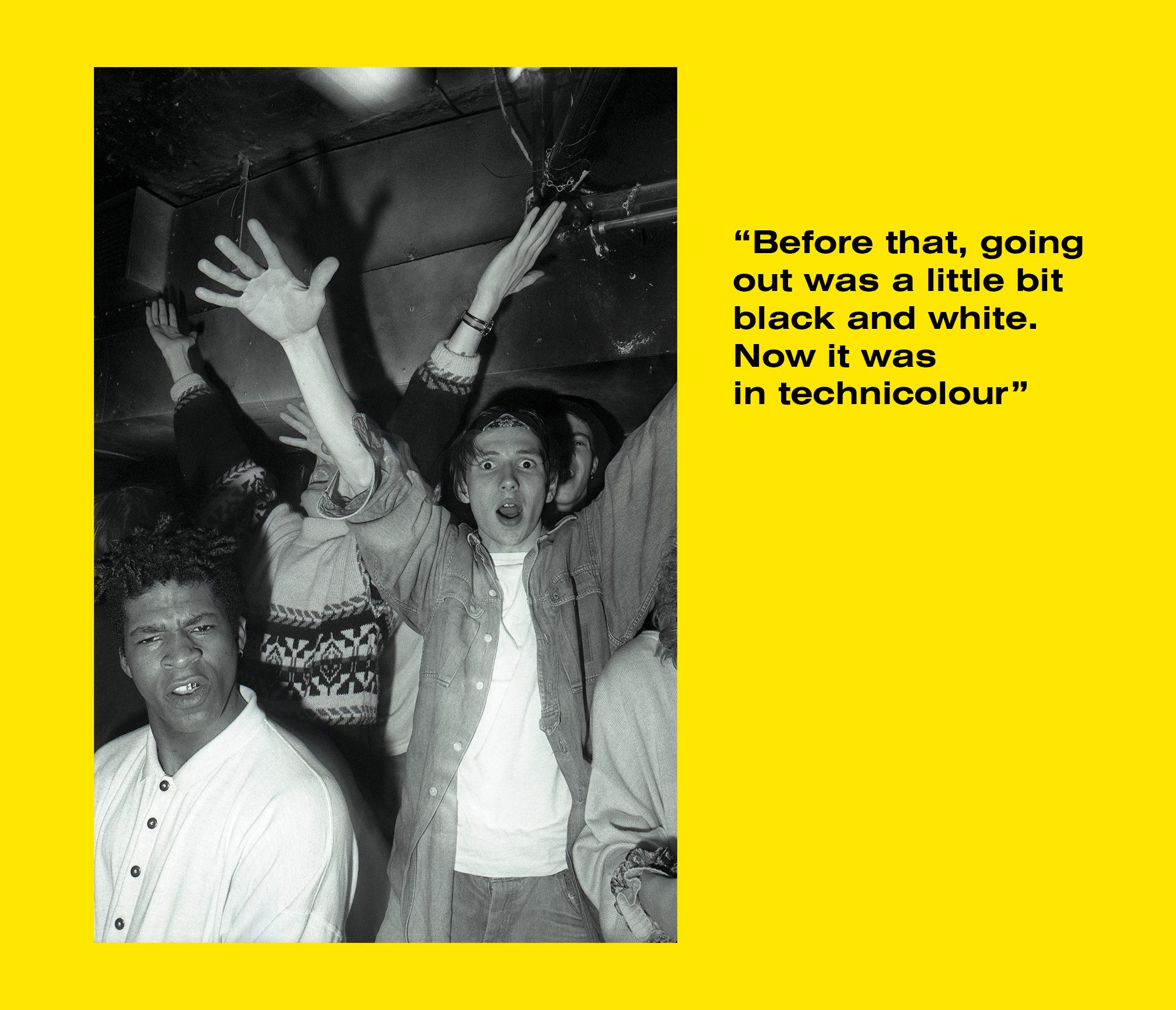

No A-Levels or degrees were needed in this new era of openness. All you needed was enthusiasm, a bit of chutzpah, and a bag of records. “For the first time in my life, I thought ‘this is what I want to do, this is what I need to do’,” says Optimo’s JD Twitch, who was living in Glasgow at the time. “Suddenly it was like someone had turned on the colour. Before that it felt like going out was a little bit black and white, and now it was in bright technicolour. It’s actually really hard to express how genuinely exciting that was.”

The same pattern, city to city, repeatedly. Small pockets of DJs committed to the cause and growing numbers of clubbers discovering house. In Liverpool, Andy Carroll and Mike Knowler; Graeme Park and DJ Jonathan in Nottingham; Nightmares On Wax in Leeds; Parrot and Winston in Sheffield and Slam and Harri in Scotland, while London had Colin Faver, Kid Batchelor, Jazzy M, Eddie Richards, the Watson brothers, Mark Moore and clubs like Asylum, Shoom, Spectrum, Clink Street and The Dungeons.

Jane Bussmann was a British writer working in LA when she received a package from her boyfriend in early 1988. “I got sent a cassette; it was called something like ‘The London Acid Scene’. It was very bleepy, brilliant acid house music. The letter said: ‘You’ve got to come back to London: I’m dancing like a tree.’”

Hedonism, which began in February 1988, only lasted four parties but was crucial in gathering the tribes of London together. “I was a house music evangelist,” says Nicky Harwood, aka Nicky Trax. “Hedonism was a free party in a warehouse and it was just great. At that point the soundsystems weren’t any good in any of the clubs, and it was the first time I’d heard house the way I felt it should be heard: in a warehouse space, with banners hanging, banging speakers, laser and smoke machines. House music all night long.” Danny and Jenni Rampling, whose Shoom parties had initially inspired Hedonism, were married on the same day as the first party, and celebrated their wedding that night in a warehouse in Alperton.

There was another magical ingredient that had turned house music from a fad to a phenomenon: ecstasy. “Ecstasy was the accelerator,” says writer Matthew Collin. “Ecstasy was the drug that bound people together. It didn’t create the music, but it did help to create a community around it. And it gave it

that passionate intensity. Of course, there would have been an electronic dance music culture without it, but it definitely wouldn’t have happened in the same way.” Once they’d been thrown together, it seemed as blindingly obvious as two parts hydrogen and one part oxygen.

The change was dramatic. Noel Watson, along with his brother Maurice, had been playing house since its first arrival in import stores in the mid-80s. The initial reaction at their London night Delirium was so negative they had to install a cage around the DJ booth to protect themselves from flying bottles – but ecstasy changed everything. “Suddenly everybody who was anti-house music loved it,” recalls Watson. “They were hugging each other. It was amazing. I’d play ‘Strings Of Life’ and people would go mad.”

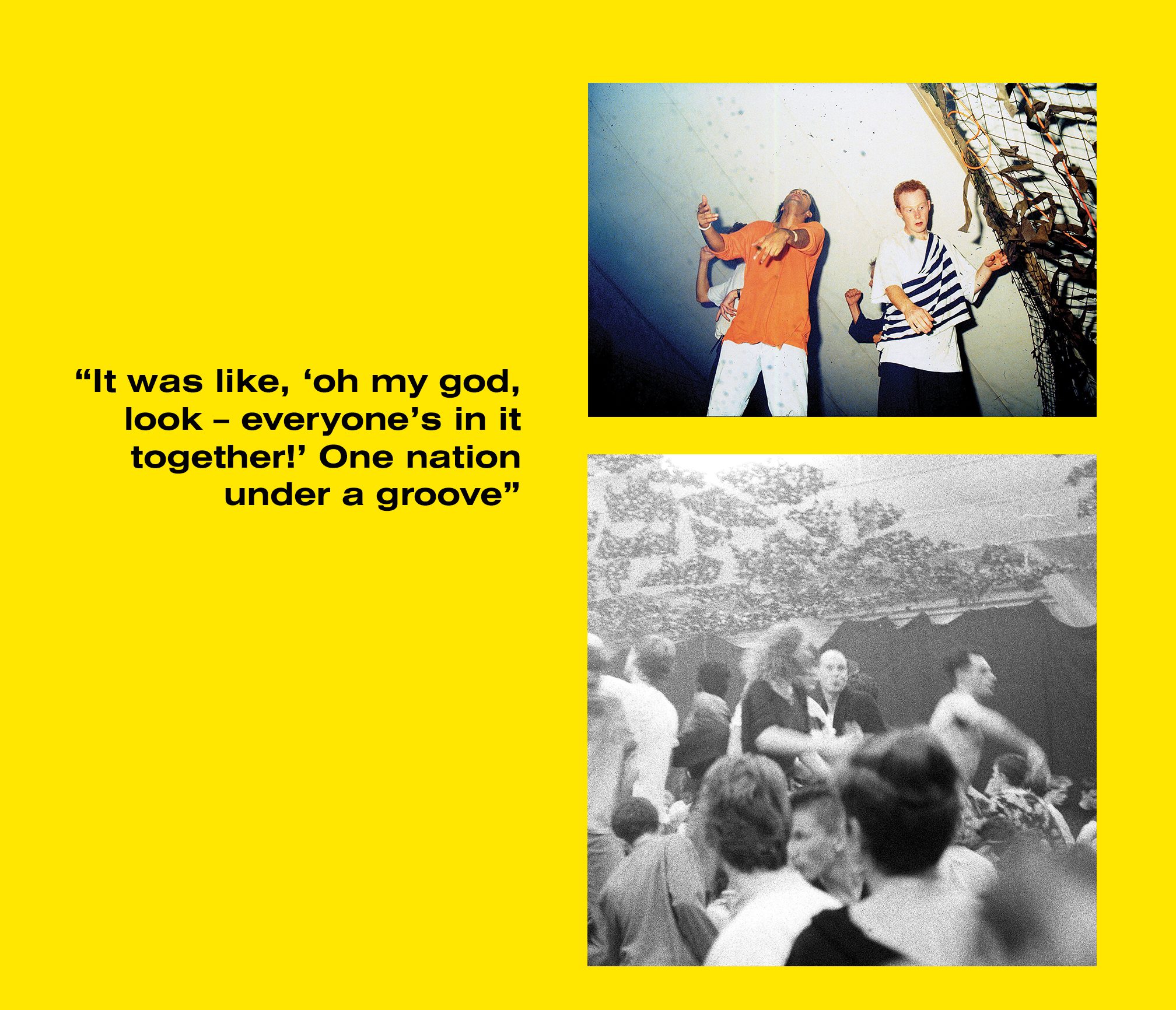

In Manchester the resident DJ at The Haçienda’s Friday night, Mike Pickering, had been playing house since the first releases on Trax in 1985. By 1988 he had built the night into one of the strongest in the city. Then ecstasy arrived. “We were going to The Haçienda before it all kicked off,” recalls clubber Catherine Obi. “And then we walked in one weekend in our normal club outfits – black tights, DMs, MA1 bomber jackets – but people were all in T-shirts, sweating. I was like, ‘What the fuck is going on?’ Within a month we’d had our first pill and we were just loving it. It was very, very strange how quickly it switched. It was like mass hysteria. But that was what was so good about it. All of a sudden it was like, ‘oh my god, look – everyone’s in it together! One nation under a groove’.”

Drum ’n’ bass don Fabio discovered Paul Oakenfold and Ian St John’s London night Spectrum after a friend recommended it. “Me and a couple of lads from Brixton walked in and they were like, ‘What the hell is going on here?!’ It was a Monday night, everyone with smiley T-shirts, big eyes, chewing their teeth, just walking around in another world. They said, ‘It’s like we’ve walked into hell. We’re going back to Brixton.’ They fucked off and left me in there. I just remember looking up seeing Paul and this smoke and him being like a fucking deity up there. I thought, ‘My God, this is absolutely fucking amazing.’”

Acid house opened up a whole index of possibilities. Weekends would start around Thursday teatime and sometimes not end until Monday morning. All the old certainties (and clothes) were thrown out, replaced by new friends, new music, new everything. “1988 and 1989 were special times, but in different ways,” says Haçienda resident Mike Pickering. “It changed our lives, both personally and professionally. Everyone I know from that period dumped girlfriends or boyfriends, and met the loves of our lives.”

“You’d find yourself on the roof of a tower block in Elephant and Castle eating croissants with some television repairman wearing a boiler suit called Harvey, who puts his hand in his pocket and pulls out a puppet of himself: ‘This is Harvey too!’” says Jane Bussmann. “It was all fine. Then you’d go downstairs and jack to Fast Eddie. Absolutely brilliant.”

It took some time for the authorities to work out exactly what was going on. Confusion reigned. The word ‘acid’ puzzled many as to the drug of choice

(in actual fact many people were taking acid, since it was significantly cheaper than E). Then the press scares started. While parents saw ecstasy as a step down from heroin, kids saw it as a step up from beer. In the autumn of 1988, The Sun ran a special offer for their “groovy and cool” acid house T-shirt, featuring two models who looked like they’d been dressed by your mum. Three weeks later, the tenor changed: ‘SHOOT THESE EVIL ACID BARONS’. But the newspaper headlines merely served as recruiting sergeants for every teenager in the UK. “The massive free advertising campaign by The Sun was very generous of them,” laughs former Mixmag editor, Dom Phillips. “Once the tabloids had written that 5,000 kids were dancing all night on drugs and having sex, 500,000 kids were asking, ‘Where’s the party?’. It was just so obvious.”

Margaret Thatcher’s helpfully repressive government provided the perfect conditions for acid house to gestate. Yet politically, the scene was a contradictory mixture of the entrepreneurial and anti-authoritarian. After experiencing a revelation at Shoom, outdoor rave promoter Tony Colston-Hayter best summed up the pioneering spirit of money-making with his Sunrise parties that also, in fairness, helped turn acid house from an urban cult into a national craze. In an era of mass social unrest and workers’ strikes, it’s unsurprising that some felt the scene was a reaction to Thatcherism. The Clink Street parties, for instance, were formally named RIP: Revolution In Progress, while many in Scotland immediately saw links between the poll tax and raving. “Thatcher particularly hated Scotland and was always enacting policies here, like the poll tax,” explains JD Twitch. “If there hadn’t have been a Conservative government in power, who knows whether it would have taken off in the same way?”

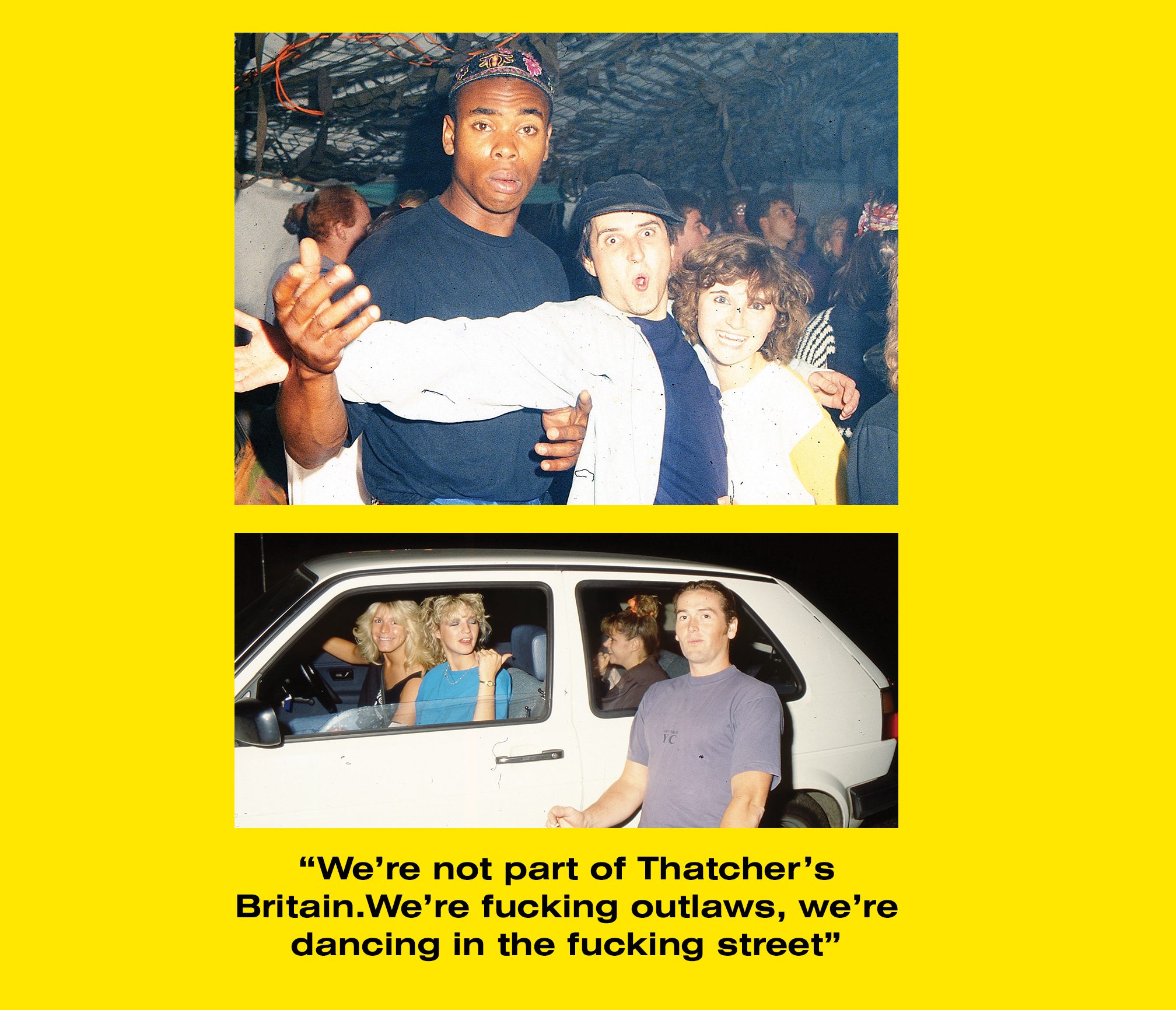

“Coming home at noon with a tie-dyed top on, dripping with sweat, or walking into a petrol station in bare feet, you really did feel like an outsider,” recounts Fabio. “We felt glad to not be part of Thatcher’s Britain. ‘We’re nothing to do with you. We don’t do nine to fives, man. We’re fucking outlaws, we’re going around with bandanas on our heads, dancing in the fucking street’. You had an allegiance with anyone with a smiley badge. It was like a code. You’d see it and you’d be like, ‘Yeah, shhhhh’. It was a secret fucking society. It was Thatcher’s Britain at the time, and we were like, ‘Fuck Thatcher! Fuck the Tories!’”

The ripples from this youth eruption crossed the North Sea, the Channel and the Atlantic. Many of the early raves in the US were directly inspired by the events in the UK. DJ Randy Moore, having spent time with Oakenfold and Mark Moore earlier in the year, threw the first acid house party, Sextasy, in LA in 1988, alongside fellow promoter Mr Kool-Aid (Steve Enis). Forty people turned up and danced to strobed-out house. Recent Manchester emigré Michael Cook, realising he’d moved at precisely the wrong time, hooked up with the pair. “I was trying to be part of something that I was hearing about back home, to see if we could make something similar happen here,” says Cook, who became one of LA’s leading DJs. In New York, DJ dB, a London ex-pat, started throwing raves that eventually turned into the hugely influential NASA.

It infected everyone it touched, everywhere it went. Frenchman Laurent Garnier had moved to Manchester to work in his sister’s restaurant, but soon found himself DJing at The Haçienda. “You could reach out and almost touch the energy,” Garnier wrote in his autobiography Electro Choc. “It was almost religious, like a ritualistic mass. I swear at that point was experiencing pleasure close to an orgasmic high.” He moved back to Paris to start acid house nights at The Palace (the very first acid house night there, Jungle, was another British production, featuring Colin Faver). Danish DJ and producer Kenneth Bager not only danced to house in London, but played at places like Spectrum, too: “The energy was amazing and the air was full of love; a special togetherness I have not seen since.” Inspired by it (and by Ibiza), he started the Coma Club in Copenhagen. It still runs today.

Britain’s Summer of Love did not end in 1988. It didn’t even end in 1989. It was a rolling, rollicking adventure that only hit the buffers at the end of 1990. The party seemed to go on and on, building momentum. 1988 may have been the Summer of Love, but 1989 was the year that acid house went mass market, into warehouses all over the country, like the infamous Blackburn raves, the London Orbital outdoor parties and, in Yorkshire, the greatest mass arrest in British history, when 836 ravers were arrested at Love Decade in July 1990 (Rob Tissera, the DJ that night, was jailed for his role in it).

THE LEGACY

Apart from learning to dance like a tree, what was the Summer of Love’s real legacy? Back then, for a time, it felt like the world was going to tip on its axis, that society was going to shift and alter dramatically. But here we are 30 years on with a Conservative government making swingeing cuts while planning to maroon us on a swiftly shrinking iceberg floating away from Europe.

But the Summer of Love was in no way a failure. It changed our views on sexuality, race and class. As Genesis promoter Wayne Anthony says: “It would have taken decades and decades of awareness campaigns to bring us all together. MDMA did more for multiculturalism than anything the government has ever done.” Acid house influenced advertising, film-making and art. It worried governments so much they introduced legislation to control it. It terrified breweries to the point where they introduced hilariously lurid alcopops to tempt kids back to booze. It transformed city centres and ushered in a new era of late-night licensing. It changed the way pop music was consumed. It changed pop itself.

“I remember thinking at the time, ‘We are changing society, everything is going to change’,” says JD Twitch. “And in some ways I think it did. People who worked in dead-end jobs and hated their lives, it opened them up: ‘I don’t have to live my life this way’. People who wanted to do something creative but didn’t know anyone that did that, it opened up a space for them to do something different. In that sense, it changed a lot of lives.”

“It brought what were previously the pleasures of the bohemian elite to the whole of society,” says Matthew Collin. “In practical terms, it brought about changes in licensing laws, it changed city centres through fuelling a night time economy and, of course, it normalised drug-taking. Its do-it-yourself ethos also enabled the democratisation of creativity which has produced today’s huge and wonderful body of amazing music.”

What happened yesterday is what has allowed us to make today better, and the future bright. The values of the Summer of Love continue to influence a generation of young clubbers who are actively engaged in club politics, from the rights of transgender dancers to safe spaces for women, and whose activism has also been instrumental in the mushrooming of female DJs on our scene – nowadays some festivals have a 50/50 gender booking policy. Unthinkable in 1988.

JD Twitch is equally enthusiastic about the here and now. “We have better sound now than we ever have had. We’ve got better DJs than ever have had. The art of DJing has come on so much, and the technology has allowed it.” To assist and support that, we now have a body of literature that existed only in people’s memories in the 1980s. There are university courses studying our history, and sound engineering modules that specialise in electronic music. Our world has changed, and it’s for the better.

The idea of a Siberian woman DJing at a festival in Brazil would have been as fanciful as travelling to raves with jetpacks in 1988, yet today this is where we are. Upon the shoulders of the early pioneers, we have created a scene that is global and, thanks to the internet, seemingly within the reach of anyone. We have amazing festivals from Holland and Croatia, from Singapore to San Francisco, from Australiato South America (take Creamfields Santiago, a Latin-American festival which originally started in a small dive in Liverpool). We have parties today that, while perhaps not as revolutionary, are the equal of anything we had in 1988. The Summer of Love continues to this day, the map of clubs and festivals painting a huge swathe across the globe. And if you squint a bit, it looks like… is that a giant smiley face?