Comment

Comment

Ecstasy island: How MDMA reached the UK in 1988

What a time to be alive - Mike Power, author of Drugs 2.0 and regular Mixmag contributor, has traced MDMA's roots and drawn them up for Mixmag

It’s like a question from a pub quiz in a K-hole: what links a hippy chemist, Margaret Thatcher, a free love cult in Oregon, European football, and the Happy Mondays? The answer is Ecstasy.

Here’s how. In the UK in early 1987, most city’s nightclubs were violent dens of sexual harassment and terrible music. A time where Hofmeister made a business selling vile cans of 3% lager. A desperate time by any metric.

Fast forward a year or two, and tens of thousands of previously uptight Brits – even heterosexual footy hooligans – were ecstatically embracing each other, dancing til dawn to house music in fields, quarries, warehouses, nightclubs, and basements.

So what changed?

The answer, of course, was the influx of a new drug: Ecstasy, or MDMA, and a new subculture, acid house. But where did MDMA come from? What strange coincidences took it from the laboratories of a German pharmaceutical firm in 1912, where it was first synthesised as a blood-clotting agent, to the darker corners of Manchester’s Haçienda in 1988, or Danny Rampling’s infamous Shoom night at a gym near London Bridge the same year?

It all depends how far you want to go back, but a salad bar in Wasco County, Oregon, in about 1984 is about as good a place as any. Cult leader Osho, – Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, who is the subject of new Netflix documentary Wild Wild Country, was the leader of a sect of free-love devotees named the Sanyassin who dressed in orange robes, and lived on a ranch in the hills. Free love, chanting, crazed dancing and delusional beliefs were standard.

MDMA had been used by progressive psychiatrists for couples counselling in the US in the 70s and 80s, after the drug was resynthesised by pioneering psychedelic chemist Alexander Shulgin in the late 1960s. It escaped the shrink’s sofas to the dancefloors of the Starck nightclub in Dallas, where the drug was sold, legally, over the bar in 1984. The drug filtered from the Starck to the Osho commune after MDMA was outlawed in the US in 1984, and then moved to Ibiza with the Sanyassin, say informed insiders.

The cult members fled their commune following a 1984 bioterror attack, in which they laced salad bars in the state with salmonella in a bid to lower turnout in local elections and win more votes for their own candidates.

In a beautiful coincidence in the mid-1980s, many young men and women, especially those from deprived urban centres of Manchester and Liverpool in the gruseome Thatcher era, would travel to Europe looking to make money, watch European cup matches, and generally escape the gloom.

“Back then you could get an emergency ‘loan’ off the dole office for a cooker or a bed or some shoes or a suit for an interview,” recalls one former giro-fuelled European wanderer. “We just cashed the cheques and did one to Ibiza,” he laughs.

Back then, Ibiza still offered the opportunity of cheap drinks, cheap rent and an easy hustle for lads more used to selling hash round Whalley Range or Toxteth.

“I was at Amnesia watching Alfredo play, off my tits on MDMA in 1988,” one former raver told me. “All I wanted to do was get everyone I’d ever met on it. I have to admit that I went a bit weird for a bit. I thought it was going to change the world. Make things fairer. Bring us all together a bit.”

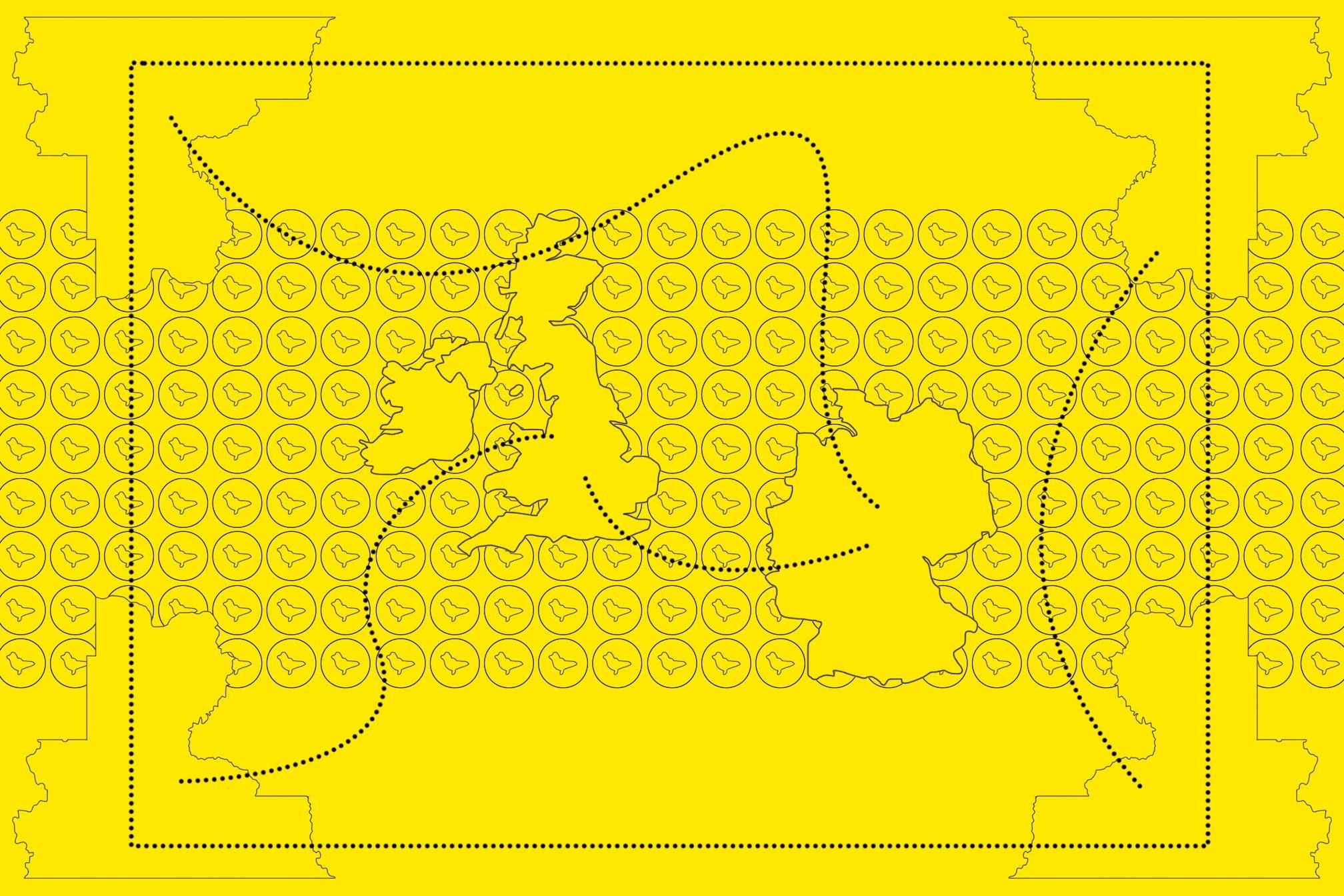

The sanyassin quickly created distribution networks from chemists in Holland into Ibiza, London, Liverpool, and Manchester.

Here’s where the trail must be left deliberately vague, not only because it involves crime, but also because at least three different groups of people claim the credit for bringing Ecstasy to the UK for the first time.

In September 1987, four London club and pirate-radio DJs – Nicky Holloway, Paul Oakenfold, Danny Rampling and Johnny Walker were having their own first experiences of Ecstasy in Ibiza and returned to London to promote nights first at Shoom and later at Heaven (though these promoters and DJs were not involved in dealing MDMA in any way).

Drugs were sold fairly openly at both clubs by a few teams who say they scored the pills from Dutch criminals and travelled to the UK by ferry, in those far-off, pre-CCTV days.

“We just used to drive on with 10,000 pills at Calais in bottles of vitamins. No one really knew about Ecstasy. The police were clueless. We didn’t care anyway,” one dealer told me. “Once the massive orbital raves started, though we had to stop as old-school London gangsters took over.”

A shipment of over 15,000 pills were smuggled in to the UK from Amsterdam by people close to the Happy Mondays in late 1987, and these fuelled the rise of acid house in the north of the UK, according to someone familiar with the band and the deal. These friends of the Mondays began to sell it in an alcove near the speakers in the Hacienda known as “E corner”.

A third group of user-dealers from Manchester told me they bought 200 pills in from the US in 1987, which they say were handed out like a sacrament at Stuffed Olives, a gay club in Manchester.

Everyone wants to claim the Ecstasy crown, but it’s perhaps more romantic to leave the central origin myth of rave culture a little mysterious.

In the clubs, meanwhile, short hairstyles fell out of favour to flowing hippy locks, with baggy clothes, fezes, or silk pyjamas reported in the weirder corners of Mancunian nightlife. The soundtrack was just as weird and radical: acid house.

“There was so much amazing new stuff arriving from Chicago and Detroit on a weekly basis,” says DJ Graeme Park who DJed at the Hacienda that summer with Mike Pickering.

“We’d put something on not knowing what it effect it would have. It might be a drumroll, or an acid riff and it would just spread across the club. It was explosive. Then we’d we look at each other go: “What the fuck are we part of? We knew something incredible was happening. It was the start of something new. We felt part of the audience. We were part of them,” says Park.

Today, Ecstasy is sold on darknet markets to customers using cryptocurrency and wi-fi connections and encryption. None of these things existed in Thatcher’s Britain in 1987.

But just as technology and music and culture may change, the drug that lies behind it is changing too: Ecstasy is stronger, cheaper and more popular than at any time in its bizarre 30-year history on this rainy, hedonistic, still extraordinarily unequal, and never-more-divided nation.

Mike Power is the author of Drugs 2.0 and a regular contributor to Mixmag. Follow him on Twitter