Features

Features

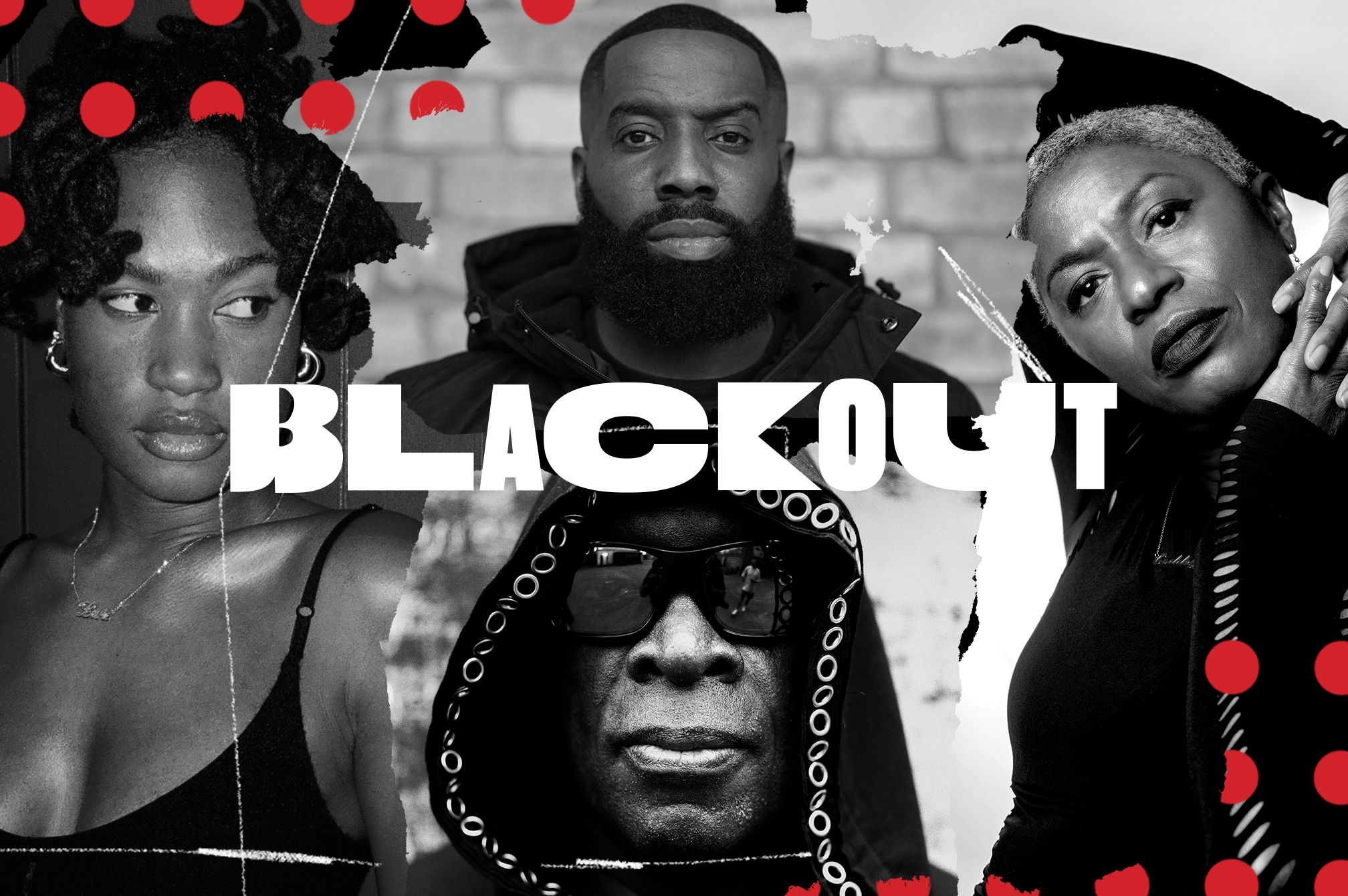

The Blackout Electronic Music Roundtable: Kevin Saunderson, DJ Paulette, Lovie & Kwame Safo in conversation

Kwame Safo hosts an expansive conversation with Kevin Saunderson, DJ Paulette and Lovie, reflecting on their journeys as Black electronic musicians, navigating the industry, and joining the dots between the past, present and future of dance music

Kwame Safo: Four individuals, three different time zones. I deeply appreciate that you're all here with us today. Kevin Saunderson, who is guest editor with me on this issue of Blackout Mixmag, DJ Paulette and Lovie. A space that we can be really candid about our journeys, some of the things that we've identified beyond the music.

I think I'll start by asking a pretty broad question, but I think it gives enough room for everyone to expand. I want to ask, how has your journey in electronic music been so far? Can I start with you, Kevin.

Kevin Saunderson: I've been at this for about 40 years, so my journey falls back into my early inspirations, moving from Brooklyn at the age of 10 to a suburb of Detroit, Inkster, Michigan. And then onto a city called Belleville, which was quite eye-opening. It was probably seven or eight Black families that lived in my subdivision, if that, then some from another area went to school with me. So I ran into some difficulties. First thing is, when I moved from New York to Inkster to Belleville, I never knew what racism was. I had to deal with that, as soon as I moved to Belleville; I had people calling me names that I didn't even understand what they meant at the time, because I was naïve and just didn't have that... everybody was the same to me; Black, white, it didn't make a difference. So I found that people didn't like the fact that the area I lived… it wasn't for Black people, we weren't worthy of living there. I lived in an up-mid class type of neighbourhood.

Through junior high school I met Derrick May, Juan Atkins, so from the age of 12. I played sports and I met Derrick, and he really connected me into a different world. Even though I lived in New York and I used to go back every summer, and my ear was very connected to disco, four-on-the-floor, stuff like that, Derrick was the main reason I got into making music. I met Juan through Derrick, and through that, our relationships over time led me into making music. Even back then, my inspirations was really a fusion, from disco to even some early electronic music that I heard, electronic bands, like Kraftwerk, Depeche Mode, New Order, but also Parliament, Funkadelic, Rick James, Prince, Earth, Wind & Fire, so I had this fusion of sound within me. I didn't try to make funk music, I knew I wanted to make four-on-the-floor dance music. I knew there was a void in music. So my history starts really from 1983, starting to become a DJ, that was kind of the beginning.

Read this next: Detroit to London connection: Kevin Saunderson and Fabio & Grooverider in conversation

Kwame Safo: I think this is really important as well, because people reading can begin to build a tapestry of your lived experiences, their lived experiences, seeing if there's any synergy, any similarities, and a connection can be built.

DJ Paulette, I've got your wonderful book here with me, Welcome To The Club: The Life And Lessons Of A Black Woman DJ. I think it's really powerful and again it's an honour to have you here, because being explicit regarding who the life and lessons are for, and the nuances of capturing it in that title is really important, rather than it sort of being muddied up together with the experiences of men in the scene. So, how has your journey been so far in electronic music as a Black woman DJ?

DJ Paulette: I am a Manc born and bred, from Manchester in the UK and my family are all into music. My brother was a DJ, my mum and dad, for a short time, were co-owners of a nightclub in Manchester called the Ebony club, and it was one of the first places, really, in Manchester where Black people and white people could party together.

Because what people don't know about the UK, for a very long time, there was indeed a colour bar [segregation]. So Black people partying in the UK, the clubs we went to were limited, the clubs we went to were generally on the periphery of the city centres, we weren't really welcomed in the city centres. Through the '70s, '80s and early '90s there was something called the 'sus laws'. So Black people, we found a way to party, and we had really cool parties, but it was always very much on the edge, and very much not included.

The really big Black music parties were generally run by white people, so you get people like Colin Curtis and Greg Wilson, and they were really famous for running these great jazz-funk, soul all-nighters, but you know, generally frequented by mixed crowds. But Black people couldn't get the licenses for parties. This is kind of what I've come through.

I'd never planned to be a DJ, but I had lots of records and by happy accident I met somebody who was putting on a party in Manchester who couldn't afford to pay a DJ, because she'd spent all her money on hiring the club and posters and advertising and all that. So I did my first gig at the Number 1 Club in Manchester, a really cool, underground, queer club in Manchester, and it went really well. I played all night, 9:PM til 2:AM for £30. It was a lot of money then! But I actually spent £150 on records. But that was the investment, and the investment's paid off 'cause 30-odd years later here I am still DJing.

I would say that, had I not started DJing on the gay scene, there would not have been a space for a female DJ like me to even happen. Because in all the time that I'd been clubbing in the UK — whether it was a jazz-funk party, or, I was also on the post-punk, indie-electronic scene — all the DJs that I followed were white, straight guys. And I never saw a woman behind the decks, ever, until I stood behind the decks myself. And I think if I hadn't started on the gay scene there would not have been that space for me. But the night that I started DJing at, Flesh at The Haçienda, they really encouraged and really, kind of, used women as part of the recipe for their beauty. The recipe for their success came from it being a queer, lesbian, and their friends, space. The women that were employed at that night got equal billing, equal sets to the guys that were also playing. So my name was on every flyer, it was on every poster, and that's how I started. How it kind of went on after those 30 years has been very different.

Read this next: How Black music record stores changed UK music forever

Kwame Safo: Thank you so much Paulette. And just to add to the context of how much you've achieved in your career, you're currently out DJing in Australia at the moment. You're not down the road in Manny! It's been an amazing journey.

Lovie, thank you for taking time out to be with us. I love your passion for radio. I would like to hear about your creativity, your generation, what's brought you into the electronic music space as well.

Lovie: I just want to start by saying, I'm just happy to be here. I'm honoured. It's occurring to me, as the two of you are speaking, that a lot of the ease and flow and abundance that I've seen in my trajectory as a DJ is because of the groundwork that both of you have laid, and because of a lot of the sacrifices, and because of having to be the first in your fields in so many ways.

Entering into the online radio space, has flowed incredibly well for me. I started my online radio show - summer school radio which is now weekly at The Lot Radio - during the pandemic, it was my pandemic project. I knew for a couple of years after stumbling across DJs at art school that DJing was what I wanted to do, but it took maybe four years from that first discovery to everything shutting down with the pandemic to even have the space and time to really dig my heels in and explore.

I saw gaps as a Black American woman who wanted to play Black American soulful music. I was not finding many DJs who were based in the US who were doing that, not many Black women who were doing that. That was a void that I saw and that was a space that I wanted to fill. Since 2020, it's become a space where I have been able to deeply explore all of the expansiveness of what Black diasporic music has looked like, really from the '60s on. And a very diverse community has really surrounded me; Black women especially, but beyond that, a diverse community has really surrounded me with my radio show and with everything that's come from that. Especially with it now being every week on The Lot Radio, it's just been a joy. But I really am in so much gratitude to the foundations that both of have laid for me.

DJ Paulette: I think it works both ways, by the way. That kind of inspiration comes both ways, so thank you for what you're doing.

Kevin Saunderson: That's true, inspiration comes both ways, because then when you see somebody you've inspired, sometimes you get re-inspired from what they're doing.

Kwame Safo: I can definitely feel an energetic circle happening even in the beginnings of this conversation. I think a lot of that will be because, what I'm also trying to demonstrate through the Blackout Mixmag is how much we are connected through our experiences, even through this music genre, and we pick it up at different eras with different technologies, under different political administrations. And yet there's still some sort of consistency happening which all unites us. That, if you put us in a nightclub, different ages, different genders, sexualities, and so on and so forth, there's gonna be this common narrative which connects us. Blackout is trying to build that tapestry, that union, so that we can all collectively find some way to solve this and make a better tomorrow.

DJ Paulette: I think what Black people are really good at doing is taking the very bare elements of what we've got, whether that's basic technology, or whether that's, 'Oh, there's nobody doing what I'm doing'... you know, a lot of people might go, 'Well, there's nobody here, so I can't do it', but I think really what Black people do is, 'There's nobody here so there's a gap, and I can go for it'. I can do what I want to do and see if other people will join me in the journey. And we are great at bringing other people along on that journey as well, and making something really beautiful out of, you know, whatever the ingredients are that you have in your fridge. If you have a few carrots and an onion you'll make a nice soup. And I think that's what Black people do.

Kwame Safo: I agree. There's definitely a je ne sais quoi in the way that we are very resourceful during hard times.

I'd like to ask Kevin, I don't want to use any sort of broad strokes, but, if you were to talk about anti-Blackness, that first time you're experiencing racism as you've touched on in Belleville, and when you pour into the mix socio-economic challenges and so on and so forth, how have those challenges been in amplifying the work that you and your friends were doing at the time?

Read this next: How Kevin Saunderson’s Reese bassline transformed UK dance music

Kevin Saunderson: If I go back to those times, leading up to now, I think what we've done — myself, Juan, Derrick, Eddie Fowlkes, Santonio, Blake Baxter, the guys who were first making this music, all of us — we had something so unique and so special that it couldn't be ignored. And we were all resourceful, even if we only had one keyboard here, and another guy [there], we brought our shit together so one person could use it. So, that helped us.

At the time, when I was creating this music, even though you had racism around you and segregation, the radio played this and this radio station played that, I just really ignored all that shit. My vision was always, 'This music is for the world', no matter what we had to go up against.

The UK played an important role, because they embraced us. If we had to rely on the US it would be a different story. I feel like the people in the UK didn't listen for colour, they listened to the music. It wasn't as segregated. At least from what I felt. I didn't live there, so I don't know for sure, but that's what it seemed like. People were just amazed, they just wanted to grab a hold of.... Something of what we have done was doing something amazing to people. Us, along with the house music scene in Chicago.

I had success with Inner City, several underground records, Reese bass, you name it. As time went on, what I found is, there was a lot of capitalism, and especially in America, a racism... it was only us few, so I felt like our music kind of got kidnapped. And, in a way, of course people were inspired to make music, but we didn't really have the same opportunities as some of the other known DJs that became really famous. And nothing against these DJs, they were doing what they did. At the time, I remember people like Sasha & Digweed, Paul Oakenfold, they all was taking off in the UK, which makes sense. But then they came back to America and they getting booked over there, but we couldn't get booked. So I found that to be a battle. I found people like MTV didn't really support our music, especially the Black side of things. I feel like the magazines, the publications, the promoters, all of that was like, 'This is ours. Thank you, but this is ours', you know? That's what it felt like. It's always been an uphill battle.

When we first started this music, the only people that would dance to it was the gay clubs and Black audience. And when I say Black audience, I mean like, we had a show here, I don't know if you heard of it, called The Scene, and then they changed it to The New Dance Show. 100, 200 Black people dancing to electronic music, techno, house. It was amazing. When you go back and look at the clips, then you think like, well R&B was kind of slow, and you had hip hop, but this, all this shit was fast. At one point I was thinking, 'Well OK, we make music, it's a little too fast for Black people’, but it couldn't be because I'm Black, you know?

So all that got lost through this whole inspirational music going to Europe, coming back to America, and then Black people who did hear music which they thought was house or techno, they wasn't feeling the same, or they wasn't feeling it enough to attach to it. Then there was no real support behind it to help even new artists, that maybe were a little bit inspired, who had started, but they kind of just gave up trying to knock down those doors and barriers. Sometimes it was tough times for me too, you know, even after I had success with Inner City.

Read this next: The New Dance Show: Detroit's delightfully lo-fi house and techno time capsule

DJ Paulette: You're right. The thing is, in the UK, first of all, yes, embrace the music, import the music, import the DJs, import the producers, this is what we did. I bought Inner City, Reese Project records, I bought all of them. When I started DJing, that was what I was playing. But also, like you said, the people that danced to it to start with were Black and Hispanic and queer. For me, playing house music, one of my first challenges was I was playing what was kind of known as queer music, so it kind of set me aside, even though it's music for everybody. There was an attitude to the music where I knew that I was the odd one out in my family because I was into house. My family were into soul, funk, disco, rare groove, Northern soul, everything, but house wasn't on their radar fully.

The second thing was, again, Kevin you're right, the gatekeepers. And how certain DJs seemed to get a lot more opportunities playing the music that they had been inspired by, or had been made by other DJs. So you get [Paul] Oakenfold and [Danny] Rampling and the 'Ibiza four', Sasha, getting these careers that absolutely exploded. But at the same time, their American counterparts... they were getting the love, but they weren't getting the same amount of love. And like you say, when they went to the States, they were way bigger than their Black counterparts. Which is just like, hey, hold on a minute, what's happening here?

And what we can see around that time, I was working as a publicist for Talkin' Loud. I found it very difficult to get Black artists in the magazines, in NME, Melody Maker — name your magazine, it was a battle getting Black house music DJs, producers into the magazines. But if you had Sasha he went on the cover.

Kwame Safo: In your book you spoke about 'the invisible women that keep the beat going'. There's obviously a huge and problematic energy around misogyny in music, and how the opportunities for women, and Black women, aren't anywhere near where they should be. If you were to articulate what you mean by the term 'invisible', from a branding and opportunity perspective, how has that been for you?

DJ Paulette: It happens in lots of different ways. I think, first of all, nobody likes to be like, 'Oh, crying, squish squish, it's a Black thing'. It's not always a Black thing. But it does kind of put you at a little bit of a disadvantage against other DJs who have either got less experience than you, or have the same experience than you, but just, to them, look better on the cover of a magazine, to them look better on a flyer.

Another one of the challenges is also not looking like all the other female DJs. There was a point, I think around 2000, 2001, where house music, dance music, electronic music started to be really heavily marketed to the white, straight, male gaze. So you got real sort of glamour model DJs who DJ'ed with their boobs out and wearing very little. And of a sudden it was just, like, we're selling Page 3 here, we're not really selling music anymore. So actually, [it was a challenge] managing to sustain a career through that period where it was really a 'sex sells' market for whether you got the gig or not, and the music took a backseat. So there are very, many ways that I as a woman have felt invisible. And have had to overcome those moments and be patient, and, you have to take the rough with the smooth. If you believe in what you're doing then you've got to just keep on going until... you know, 'cause nothing lasts, everything has cycles, and there will be a moment where someone takes their foot off and you can breathe again. And we can all kind of start being creative on the same sort of level playing field again.

I think it's kind of come round again with your TikTok DJs. Some of them are really super talented, don't get me wrong, but there is an element of the superficial, the look being more important than the talent or the capability or what you can do. And having to ride that out, and always having to feel like. 'I've got to prove myself' all the time, you know, you're always proving yourself. I think the moment when I decided to prove myself to myself was a great relief, and I didn't have to prove myself to anybody else apart from me, and then life just become a lot easier.

Read this next: DJ Paulette has always been one step ahead

Kwame Safo: I think there's a common thread happening regarding the burnout and exhaustion a lot of Black DJs, Black musicians feel, because there's this constant justification, you always have to justify yourself.

DJ Paulette: Relentless!

Kwame Safo: You've got the awards, you've got the accolades, you've got the videos on MTV, and yet you still have to justify yourself.

Then there comes a point where the music transforms, like Kevin was mentioning, the capitalist element is injected into it, and now it's selling a lifestyle. But we aren't reflected in that lifestyle. The lifestyle isn't Black faces, Black families, Black joy, Black dancing, Black dance moves. It's something that we can't even see ourselves in. So there is this very slow and incremental erasure of where it started and where it is now.

I was at a talk last week and I said, if you was to ask the average person where the home of house and techno is, they would probably say Ibiza and Germany. They wouldn't say Detroit and Chicago, and that's because there's been such a long period of time of this constant imagery being projected that we have to do so much work with these sort of conversations, sort of reposition things.

Lovie, how are you finding in your journey since the pandemic, as you've starting DJing, you said the catalyst which sort of brought you into that space was not seeing enough Black female DJs like yourself. So how has it been for you?

Read this next: The unsung Black women pioneers of house music

Lovie: To add additional historical US context, it was amazing for me to learn just how many systemic infrastructural changes were put in place to keep Black dance and electronic and house music from succeeding in the United States. I think that, as much as press and coverage and visibility and the image of dancing music globally is shaped by journalism, is shaped by these documentations, these archives that we have, it's also, as Kevin was speaking to, dance music having to go to the UK because the US didn't invest in it here, they didn't create safe dancefloors, spaces, for electronic music to take shape here and to thrive and to turn into an industry the way that they invest in it in these European countries. And then this is where you see this flight of DJs from the US to Europe, to the UK, still. In my generation, if we want to take that next step and expand our career, it looks like travelling to Europe and to the UK in the summertimes to play festivals. Not so much really investing and creating an established career in the United States, it's almost seen as a sort of limitation.

As I was learning about electronic music and dance music, in summer of 2021. my really good friend and fellow DJ Honey Bun, we were reading, we were watching documentaries, we were seeing, or rather, not seeing Black women represented in this history, and we were asking, where were they? It really was this realisation that if we wanted to shift the narrative we would have to start right away. It's already too late; we have to start it, we have to shift it.

It's been a huge, immersive learning experience for us. Taking that question of, 'Where are these faces and how can we make them?', to then starting the party that we throw here in New York called Soul Connection where we only book Black women. Paulette was saying ‘I only saw a woman behind the booth when I saw myself’. Now when people come to our party they only see women, and they only see Black women, behind the booth. That was born of understanding what the narrative is and wanting to reclaim it, and wanting to start, or at least contribute, to the shifting trajectory of house music, dance music, being born in the US of Black genus, and of Black creativity, and of Black innovation.

Lovie: It's been a very slow and steady shift. The dancefloor that we have at Soul Connection is incredibly diverse. So many Black women come to our parties, but I do think, one of the ripples effects that I see of that repackaging of dance and electronic music is the narrative that it's not ours. That it's not our sound, that it doesn't belong to us — and that's not for us to enjoy. So now what I see are Black people, who, just as Paulette was saying, they come across this music on TikTok, on social media, and they're asking, 'Where are the clubs where this is playing?'. But the clubs where this is playing are still segregated. They're still not hosting nights where mostly Black DJs and Black people are coming into the space. I'll have people reach out to me and they'll say, 'Hey, I really wanna come to your party, but I know that as a white club, so are there gonna be Black people there or no?'. You know what I mean? That's something that is still moving, pushing slowly along, that I definitely see as my responsibility with Soul Connection and with Honey Bun to shift. And really got curious and really get risky about how it is that we change that trajectory. So that they know that the space belongs to them.

DJ Paulette: It's interesting you said that about belonging in that space, because one of the things that I see really regularly, and this is in 2025, I'm behind the decks and I can be looking at a space of 200 people, 300 people, 10,000 people, and I don't really see very many Black people.

One of the things that I think is a huge challenge: are security even letting Black people and people of colour in? Because the crowds are not even. Or is it that the ticket price is so high that, you know, this demographic will not spend that amount of money on a ticket for a house music party. They might spend it for a festival, but they might not spend it for an evening out. Do we have a problem there maybe? Just simply the affordability of the party and the spaces. And also the fees of the DJs. I'm part of that discussion myself. There's a lot that comes into that 'belonging' to the space, and 'do we belong' in that space, and whether a space presents itself as a white space that Black people and people of colour and queer people will not go to.

Lovie: It's a bit of a cycle that I feel like we have to figure out how to break our way out of. Because the first question that Black people are asking is, 'Who all is gonna be there?'. They don't wanna be where other Black people are not gonna be. So it's hard sometimes to get them to make that risk. But the only way that we're going to fill up these spaces is if we make the choice to definitively go regardless. But I've definitely been able to see really beautiful Black community start to take up small but growing space, starting to take space up on the dancefloor for sure.

Read this next: Kevin Saunderson: “Techno is more than just music; it’s culture, history, and a movement that deserves recognition”

Kevin Saunderson: It's interesting here because I've played in New York, last few years I've been playing at Paragon pretty consistently, two or three times a year. I played in January, right after the New Year's, and I was like, ‘Oh, this gonna be interesting to see what it turns out like, because it's right after the New Year. So anyway I go play the gig. It's lines around the block! Right? And I'm like, it's always been good, but this was something different, you know. I was so impressed.

There was a couple of things I was impressed with. The amount of Black people, women, guys, the diversity in the crowd, I never seen it in New York, ever. Not since I've been playing in New York. So, I was really impressed with that. And maybe part of what you're doing already is taking effect. Because I didn't know you was out in New York.

I have a nephew also, he DJs, his name is Kweku, same last name, and he makes music. He had a friend who got murdered and my nephew went into a real depression. This is before he started making music. And he came here to stay with me for, let's say, a couple of years, he travelled with me, I took him around, that's how he started making music. And then, he was just amazed that we could travel all these places in the world and there was no violence, people come together. Obviously he heard me play, and other Black artists play, and thought, like, 'Oh man, this music is great'. So he started this brand called The Hood Needs House. He's out in New York. I don't know if you know of that?

Lovie: I do. I heard of it very recently actually. That's amazing.

Kevin Saunderson: That was at the Paragon, he played downstairs, and Black kids, young, vibrant, and they were chanting "The Hood Needs House". I was so proud. So, keep doing what you're doing, you know.

Lovie: Thank you.

Kwame Safo: I love that. Beautiful moments I hoped would transpire when I devised this platform, that you don't really get stuck in that trauma bond, that trauma dumping of just being pummelled of all the negative aspects of what we've been through. And then, just as you got to developing the conversation towards the horizon, the solution, the better days, that's where these articles get wrapped up or these videos get ended. I'm a positive individual; not toxic positivity, there's a lot of serious things going on. But I feel that the energy could be better spent trying to devise ways to tackle those things. And some of those great ideas don't reside in myself, they reside through having open discussion and seeing what has worked, and what is likely to work.

Lovie, you spoke about just some of the mechanisms which are starting to be put in place to make more Black people feel safer to come out, to congregate, to make young Black audiences more aware of their relationship to house music, their relationship to techno. It's something that we built, we've got one of the pioneers with us.

When I say the words 'Black music infrastructure', what more could be done beyond the journalism aspect, and the promoters, and so on and so forth, is there anything else that you feel is missing?

Read this next: Black ownership and infrastructure is needed to equalise the music industry

Lovie: From a nightlife standpoint, from an organising standpoint, I think about how inaccessible these spaces can be for DJs. And again, speaking to Black people wanting to go to spaces where this music is being played but not wanting to go to them if they're going to be the odd ones out. And so, I wonder what it looks like for us to, first of all, destigmatise DJs not knowing how to use CDJs yet. CDJs are expensive and not all DJs have access to CDJs when they're first starting out. If there are young Black DJs who are talented, who bring in their laptop because that's what they have access to using, sometimes I found that in these electronic music spaces, in these clubs, that's really frowned upon. If we're kind of fostering new talent, I think simple things like that can really destigmatise and allow more space for new talent to grow.

I also think about how segregated these nightlife spaces are. The programming can be very strict, it can be very strictly electronic music and house music. But there are so many swathes of nightlife, whether it's dancehall, whether it's amapiano, whether it's hip hop and R&B, where Black DJs are creating beautiful, safe spaces for Black people to come in and enjoy nightlife. I don't see why those [DJs and] spaces can't have a couple nights a month at these spaces where we predominantly house and techno music to be happening, I wonder if that would shift some of these places that people are messaging me and they're like, 'I heard that this this is a white club', and now they're falling in on a random night, and now they're a little bit more open.

But ultimately, when I think of infrastructure as it's been designed, especially in the United States, I think of how capitalist it is. And capitalism in the US is so inherently anti-Black. I wonder what it looks like for these spaces to be liberatory, for them to be Black-forward and centered, for them to be progressive and for them to be anti-capitalist and people first, and what ripple effects we would see from there.

Kwame Safo: Thank you Lovie. Paulette, in a similar vein, what would have been necessary to keep you more in Manchester, more in the vicinity, rather than via necessity, you had to…

DJ Paulette: Having to move! Every time I've hit the ceiling I've had to move. So I've moved from Manchester to London, I've moved from London to Paris, I've moved from Paris to Spain, I've moved from Spain back to the UK. It's really interesting to me, and also quite frightening to me, realising that I've done pretty much most of this journey on my own without backup. I've had an agent, but I've not had any sort of team behind me that can push me. In terms of the rosters of these DJ agencies, if you just look at them and see how many people of colour… you know, I'm not asking for this magic equality, diversity, all of that, but if most of the agencies have only white people on them, you know that your event space is going to look exactly like that.

I don't think we have had those same opportunities to play those enormous gigs, because the agents that book those enormous gigs haven't got any Black people on their rosters. So they're never going to suggest those artists, unless you break so big that they can't deny that they need to have you, or a few of those names, on the line-ups. You don't want to feel like you're the token, but there are the times when you realise that you're the only one on the line-up, whether it's female or person of colour. Sometimes you realise you’re the minority tick box for X amount of years, and that nobody else is getting through. New talent just isn't percolating through, and I think there has to be a quicker and better way for that to happen.

Kwame Safo: Kevin, the development of your own platform — with your family, your passing on the recipes as it were — would you say one of the reasons was the fact that you don't want to have to fight as hard and justify yourself in other spaces? When you've got your own car, you put your own petrol in, you can go wherever you want to go, so you don't really have to worry about having to be considerate or having to compromise elements of yourself if you've built your own platform. Could you tell me about your platform and your event in Detroit and what the vision is?

Read this next: A rare interview with Peven Everett

Kevin Saunderson: Even from the beginning, I built my platform through my record company KMS, because I didn't want anyone to tell me I couldn't release a record, what I had to do with it, any of that stuff. So, of ctouse, it felt like I could just do what I wanted to do.

Obviously you run into different obstacles; 'Big Fun', Inner City, was on KMS at first, but it got too big for me, let's put it that way, there's only so far I can take it. But I still kept control of my label. I have a lot of people like MK, Chez Damier, Ron Trent, I open my doors to them, mentored MK to a certain extent, but he was talented already.

Through time I still believe in being able to put out your own music and do events. I do a stage at Movement, which is like the past, present and the future, that's my concept. Two of my boys got into it, especially Dantiez heavily, and he's been in it like eight or nine years, and he's still paving his way. I got them involved with running the label, Dantiez, he runs the label, signs acts. We do these events, in Detroit mainly but we got one coming up in LA, a KMS showcase, so we try to promote new artists from Detroit.

We have an event coming up and it's based off of Kweku, The Hood Needs House. It's at a place called TV Lounge. I'm playing, Eddie Fowlkes is playing, so we got some history there. My boys are playing, JMT, and some other Detroit locals. The goal here is to keep pushing the origins of the music, keep bringing communities together.

I go to a lot of the Black schools in Detroit and speak on their career days and talk about music and making music and the opportunities that's out there, and I give them history about Detroit and techno and house, as well, because I think that's important. They might not be able to visualise it all, but they need to start somewhere. I've been in it, you know, probably the longest, close to the longest. I want to make sure I can give back, inspire youth, and also my goal is to do workshops. I've done some, but I want to do more. Of course when you travelling you can only do so much. When my career slows down, I'm gonna dip into other areas to try to springboard stuff like that. Even trying to policy advocate to try to get funding to do something like that for the youths in schools. Because, you know, we have to find a way to reach them at a younger age and educate at the same time, to be able to help them develop musically if that's the path they want.

I think we have to find a way to do that to even have a chance to get enough Black people that want to go out to clubs and experience this music, because you need awareness. We have museums, we have a lot of historical stuff in Detroit, in the city itself, they just did a techno exhibit in East Lansing, so all that stuff helps. That's kind of my angle. Just stay engaged and don't forget about the youths. I try to keep my door open to help as much as I can, of course. My kids, they're involved as well, they got their ears to the ground, probably more than me.

Read this next: Movement Festival is a celebration of techno's past, present and future

DJ Paulette: I think you said it maybe two or three times, 'the past, the present and future'. This real learning from the elders, knowing where we are, and really feeling for what the future holds and bringing that all together is really the best way that we can consolidate all of our experiences and move forward. The community, the collaboration, is really key here. And like you say, it's not an exclusive community, it's not just a Black line-up, but there is the awareness of where it came from, who we need to give the flowers, who do we need people to hear, you know, if they've not heard that name for a while bring them out. And if there's a new talent that's kind of bubbling under that is fire, bring them too. You can put those two people on the same line-up! It doesn't have to be one or the other, you can actually bring the old and the new together on the same line-up and make something really, really fresh.

Kevin Saunderson: Definitely. I play with a lot of the young, talented DJs in Detroit and, you know, I'm the oldest cat in the room but I still embrace it all, enjoy, and I see the fire in they eye, you know.

DJ Paulette: It's even when they're doing the b2bs, or the b2b2b2bs. Put an old one with a new one. Just don't go the obvious route of which two people you're gonna put together. One of the b2bs I played in the last year, there was me and Stacey [“Hotwaxx” Hale] together, and then I played with Jaguar, and there's like 20-odd years between me and Jaguar — it was a great b2b! It was so much fun. I think that's what people have to do, is just really be creative with this, and not close their minds to, ‘Oh well, if we're going OGs, it's always got to be the classics, the foundations of house, and we can't have anything new.’ It's like, we can mix this up, you know? It's OK.

Kevin Saunderson: That is considered being innovative and you don't know what can come out of that, you just don't know.

DJ Paulette: Exactly. One more thought. The way we talk about music, and the way we talk about electronic dance music culture, where we'll say the guy is a head honcho, or he's an OG, or however you wanna say it… If we have some female equivalents, and if we see who the female equivalents to those people are. So you've got Kevin, and you've got Stacey [“Hotwaxx” Hale], and if you've got me, and whoever my equivalent is, and you've got Lovie, and you see those equivalents, but all in the same place, which is why this discussion is so important. It doesn't cut everybody's roots off at their feet. It means that they all exist together, everything's happening in parallel. Can we have more Godmothers as well.

Kevin Saunderson: Stacey [“Hotwaxx” Hale] was DJing before I even started DJing, you know.

DJ Paulette: There we go, you see. We need to have this. It needs to be open. Join all the dots, not just some of them, join all the dots. Everybody's experience is relevant.

Kwame Safo: There's definitely a lot of avenues to push this thing that we've built over the course of what 40, 50 years plus to the next generation, and give it to them in a really good space. I feel as though, as we hand it over, we want to hand them over something which is really thriving, and not something that is on life support. So we have to have enough energy and all that stuff in it so that the next generation can take it to the next level.

Kevin Saunderson: One thing I think would have helped, especially in our city in Detroit, and it started out this way... you had this great festival, Movement, right, it was called DEMF [Detroit Electronic Music Festival] before. The city supported, they embraced it, right, and they put up the money for it. So guess what happened? It was free. And guess what happened? All communities came, you see more people of colour come, youths. It didn't make a difference, people had the headphones on with the babies in the strollers and all that. It was actually the most magic. So of course now, it's very expensive for people because of, you know, who's gotta be paid, and it's artists coming from all over the world. Which, I don't have a problem with that, but, if they would have just stayed on point and not deviated from it, what would have happened over time? The city's getting an influx of money, millions of dollars, because of the festival already. When I say the city, I mean the hotels, local businesses, all that. So if they woulda stayed on point with that, that also would have played a pivotal role in helping.., I know more Black artists woulda came out of this city, at least in Detroit, it definitely would have played a role.

DJ Paulette: There's exactly the same argument for Gay Pride, same kind of attitude. At first it was free, it was supported, everybody came. And then there's a point where it becomes ticketed and then it becomes this price, and certain groups of people stop coming, and it becomes more commercial, because to get the tickets to sell you have to put a bigger headliner, or a more pop headliner, and you're kind of losing the roots of it to make the money from it.

I think there's just really a need to find this sweetspot between it being a business and it being a creative industry and it being a community hub for people, for communities, to get together and enjoy the music together.

Read this next: Queer the dancefloor: How electronic music evolved by re-embracing its radical roots

Kwame Safo: I think what you and Kevin have just touched on is the value, the economic value, the creative economy, which comes from electronic music, which comes from house music. The jobs it creates, jobs which stand the test of time, because everyone here's still working really well, and working in different geographical territories that you wouldn't get with probably any other industry. With most industries you'd have to leave and chop and change and do a few different things to have that level of trajectory.

When you speak about that price point, the cynic in me sort of sees that a lot of those organisations know that they need those early doors people in it to give it the authenticity it needs to grow, but then they're prepared to lose them afterwards by hiking up the price to a place that they can't afford. And it is sad, because a lot of the life force is in that working class community. If you are gonna scale up there should always be a mechanism with companies that deal with those communities to take them along on their journey, even if it's ring-fencing a certain amount of tickets for those specific kind of people.

DJ Paulette: One thing I would like to see: just stop putting the Black women and the women on first, before anybody's through the door. And also, don't put all the women playing at the same time across every tent, so you can only see one woman at this event because you've put all the women on at 6 o'clock. Don't do that, it's shit.

Kwame Safo: Agreed. There's definitely an issue with the tokenistic way programming is done. Like, book the women, don't make any fanfare, just book the dope women and be done.

DJ Paulette: And give them a good slot! And don't have them playing for nothing. Fair and just is what I'm asking for.

Read this next: The music industry is not a meritocracy, and it's harshest on Black women

Kwame Safo: We've had a beautiful discussion about some of the things we would like to see. When I say to you the word 'future', what does that mean to you, Lovie? The future of Black music via the ethnicity, and Black music via the industry as well.

Lovie: In the future, I see Black music being owned and reclaimed by Black people, and I see non-Black people passing back that ownership to the people that it rightfully belongs to.

This is maybe less in the electronic music space, but it's been amazing to me the genres of music that I play, the soul, the rare groove, the spiritual jazz, how inaccessible it is. You know these private press records that then get picked up from right-owned repress and reissue labels that are mostly owned and operated in the UK and throughout Europe. This is music that I'm born of, that I'm descended from, that I don't own, that we don't own here in the US.

I think translating that across all genres of music, I would love to see a sense of ownership internally from Black people around this music, knowing that it's ours, claiming that it's ours, and taking up the space that it being rightfully ours deserves. And that being supported in an infrastructural and systemic and monetary way.

Kwame Safo: Thank you Lovie. Paulette?

DJ Paulette: Mine is very similar to that actually. First of all, I would say it's really important to own the story and to make sure that your story is known, because one of the problems is, Kevin addressed it earlier and it persists, there are gatekeepers who prevent those stories being known. We know where it came from, but there is a block of getting this story commissioned, written, into print, in a magazine, having the names actually solidified. You know, having those names crystalised as being the creators of this scene. So, own the story first of all.

The past is really important, but we don't have to live in it, so enjoy taking up the space that we've got, and be loud about the space that we're taking up, promote the spaces that we're taking up. Don't be shy! Because for Black people specifically, blowing our own trumpet is considered rude or we're not allowed to do that. Historically, through segregation, colour bar in the UK, you're not really allowed to big up yourself. But we need to do that, and we need to do that in the present.

The future is just really to keep minds open and join everything together. Join all the dots, as many dots of it as you can join. And just make this really beautiful tapestry of what Black electronic music actually is. Because it's not specifically house and techno. There are many shades on the spectrum in between that. And we are still only knowing very small portions of that story.

Kwame Safo: Brilliant. Finally, Kevin, what does the future look like for you?

Kevin Saunderson: Probably some of the same stuff that I already said. I have a mentoring programme that will help the future. Collaborative projects; if I have somebody play on my stage we usually try to have them do a collaborative project.

The future should be where we have some Black agents or agencies, either or, or both. But you still need enough Black artists and talent that's pushing the boundaries of music to get into that door, to have them to put out there to the public. So I think that's important. I don't know how many Black artists, even in Detroit, there are still a very small [amount].. so there's a lot of work to be done to get there. But I think we gotta have these type of things in mind to open those doors. And educate, preserve our history.

Read this next: Tyler Blint-Welsh is on a mission to document dance music’s Black pioneers

DJ Paulette: Archive. Really important.

Kevin Saunderson: Definitely. Because otherwise, if it's not done, it's like being erased.

DJ Paulette: Exactly. If we don't do it, no one else is going to.

Kwame Safo: Thank you so much. This has been a really emotional roundtable. My brain is just whirring about where we go from here and all the next steps. But I think it's actually quite empowering, energetically, feeding off of the positivity that we've built for ourselves, from real tough circumstances.

DJ Paulette: I think more than anything we want people to win! I want everybody to win, I want everybody to have their little piece of the pie, I want everyone to have their moment of success, their 'a-ha!' moment, their creativity flow moment. I want everybody to share in this industry. It's not just for one type of person, it's for everybody. And I think what we do, educating, encouraging, and inspiring, is that people know that there's people like Lovie, there's an older woman like me, there's a real OG, cornerstone of the music itself, like Kevin, who are all still pushing this thing. Pushing this culture. And saying, you know what, it is so dope, and it is firing. And get involved, engage, do your thing, and bring as many people as you can along with you.

Kevin Saunderson: That's right.

Blackout Mixmag is an editorial series dedicated to Black artists, issues and stories, first launched in 2020. Our 2025 features are co-guest edited by Kevin Saunderson and Kwame Safo (AKA Funk Butcher). Read all of the previously published pieces here