Features

Features

Is the vinyl resurgence actually helping dance music?

Digging deeper doesn’t paint quite such a gleaming picture

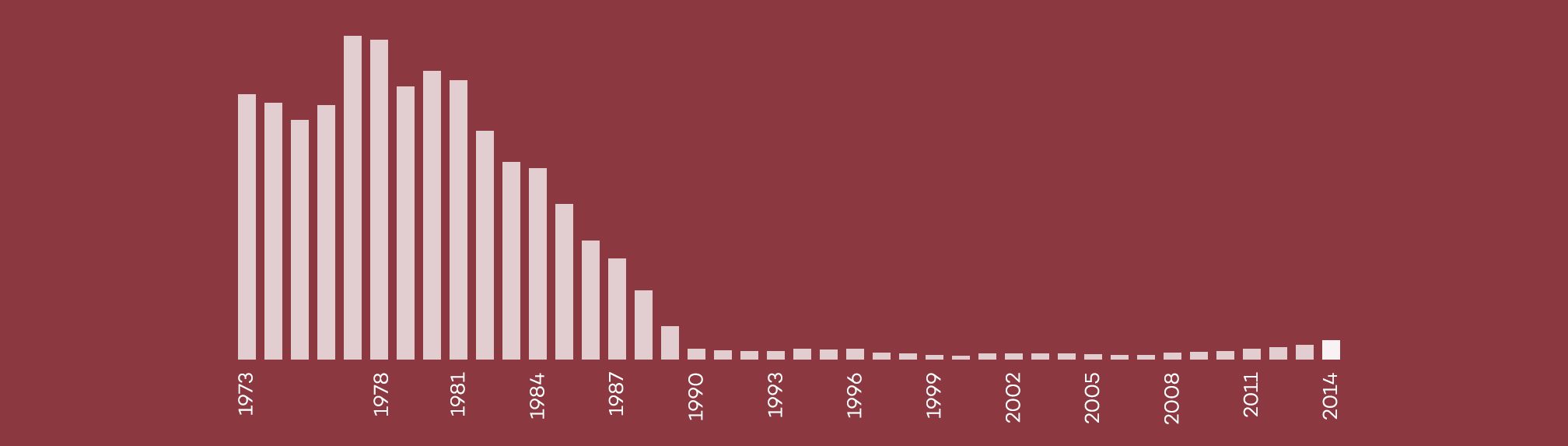

We’ve all seen the headlines, beaming proudly as they declare vinyl sales are soaring. UK transactions are at their highest point this side of the millenium; the US market has grown for twelve consecutive years, with 14.3 million wax LPs sold in 2017. There’s no denying it, vinyl is experiencing a resurgence - of sorts.

To this day, vinyl is a symbol intrinsically linked to dance music culture, and it’s tempting to got lost in the romanticism of vinyl’s unlikely comeback. On the surface, an increased interest in the format favoured for underground labels and DJs across the globe seems positive for dance music, but digging deeper doesn’t paint quite so gleaming a picture.

When a revived interest in vinyl first became apparent, the cogs of capitalism began turning, and now the significant rise in sales is the effect of major labels shipping huge quantities of Pink Floyd and The Beatles reissues, Ed Sheeran albums, and Blockbuster film soundtracks. High street shops have got in on the honeypot, with the likes of Urban Outfitters and Sainsbury’s stocking records. Last year Sony announced plans to start pressing records after a near-three decade hiatus, and Sainsbury’s decided to launch a record label after declaring itself as the UK’s biggest vinyl retailer. Independent shops and labels are not seeing an equivalent upturn in fortunes.

“It's not something to celebrate in my opinion,” says Kristina Records founder Jason Spinks of the sales spike driven by non-specialist retailers. “Trends and fads based on current fashion and lifestyle choices generally have a lot of detrimental effects that will outweigh the positives on the industry as a whole. Particularly where independent and underground music and culture are concerned.”

One example of the mainstream’s detrimental impact is the much-maligned Record Store Day. Started in 2007 to ostensibly "celebrate the culture of the independently owned record store", RSD is generally now viewed with contempt by independent dance music outlets as majors have stuck their claws in and co-opted the day to flog old hat reissues at jacked up prices. In 2018, Kristina Records will not be participating in the event for the third year running.

Peckham record shop Rye Wax also no longer gets involved in the day. Joe Howard, the Assistant Manager, told me: “While we definitely feel like there’s a need to celebrate the vinyl industry, and the independent shops that offer the grassroots support, RSD has recently been hijacked by the major label machine, who clog up the pressing plants for almost the entire year with often pretty unimaginative reissues. While this is also due to a lack of pressing plants, we felt that the lack of focus on the independent sector really undermines what the whole day should be about.”

Last year Rye Wax avoided the official celebrations and hosted its own version called The Run Out. The store enlisted a selection of its favourite labels such as Hyperdub, Príncipe Discos, Rhythm Section, Where To Now?, Phantasy and FTD to submit exclusive tunes which they cut to dubs, using local pressing business Peckham Cuts, and sold on the day. “The whole event went off and had real community vibes. This year we’re planning to ramp things up even further, so keep an eye out for that!” says Joe.

The pressing plant issue that Howard notes has put a strain on the speed at which labels can operate. The limited number of pressing plants still in operation are now working beyond capacity, and the time it takes to press a batch of records has jumped in the last decade from around four weeks to nearer three months. Delays on top of that can also occur.

Furthermore, vinyl is becoming a more expensive business to partake in, for both labels and shops. Pressing and stock purchasing rates are rising, especially in the UK. Many plants and distributors are based in Europe, and the weakening of the pound since the 2016 Brexit vote has squeezed already tight margins and inflated the market. Kristina Records and Rye Wax have each had to increase their sale prices in light of import costs rising by upwards of 20 per cent. But while Urban Outfitters can get away with selling a Katy Perry record for £38 a pop to a millions-strong fanbase of an artist who puts out one full release every three to four years, there is less customer potential in the nicher market underground dance music buyers, who are already spoilt for choice with vinyl options and more likely to be tighter with their pursestrings.

“[The cost of] pressing records has gone up at least 20 per cent since I started,” says Elijah, who co-founded the Butterz label in 2010, “and the prices haven't really gone up in the whole time I've been buying records, which is since 2005. I look at stickers for 12"s with £7.99 from then, and now, some people wouldn't spend £10 on a 12".”

Elijah doesn’t think dance outlets should play the victim, though, noting that it’s only natural that a plant run as a business would find it easier to press a run of 10,000 Spice Girls records than deal with 20 separate batches of 500 from various smaller operations. Elijah thinks the onus is on independent labels to be more proactive in pushing their music in creative ways: “We need to do better at getting new music to people, to make our records a more valuable purchase to those kind of people that are buying these things.”

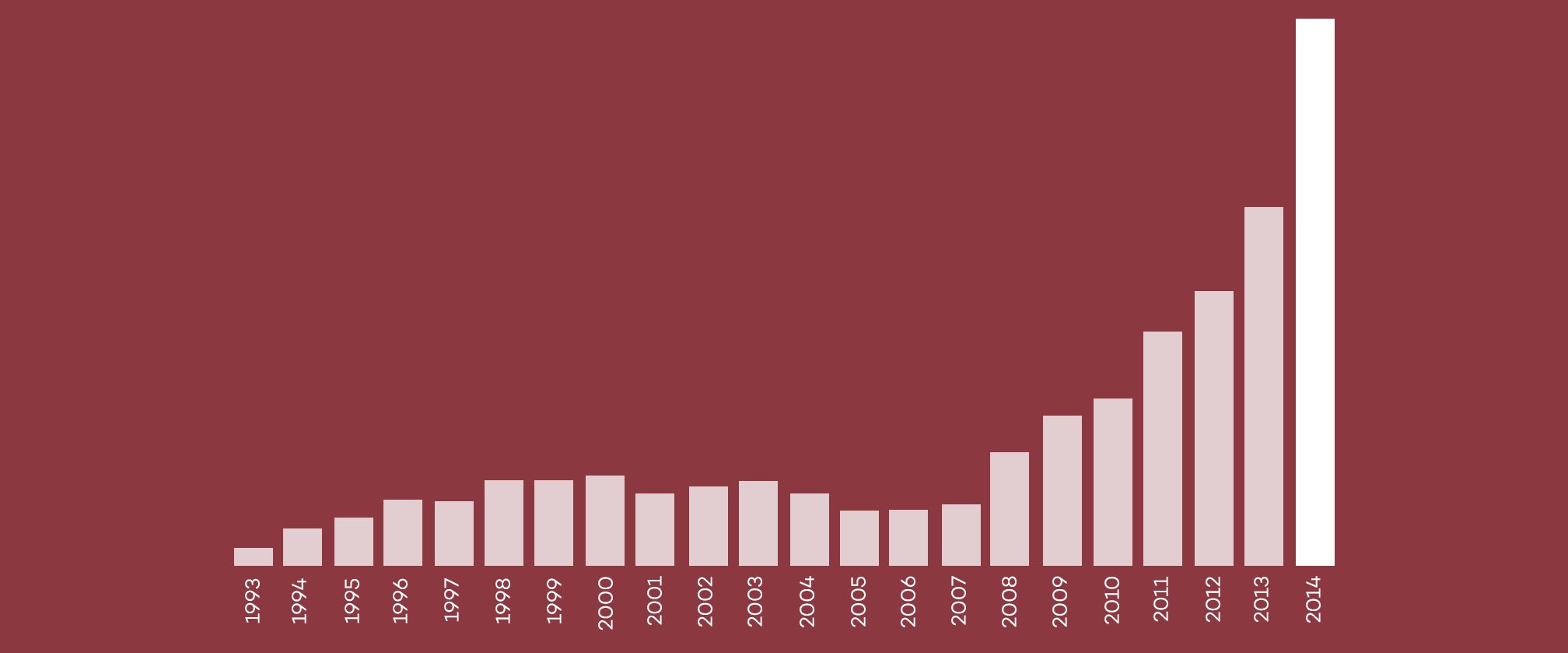

The costs involved certainly isn’t stopping new labels with a focus on vinyl springing up with pneumatic regularity. Since Rye Wax opened in 2014, Howard notes: “We have seen a massive increase in the amount of local vinyl-focused labels, which is predominantly what the shop has been set up to support, and as those labels grow, the demand has grown. We see a lot of people making trips from abroad to come to Peckham and pick up the latest tunes.

“The dramatic rise in small, DIY labels in the area has been really encouraging in the years we’ve been open. There’s now a thriving scene of indie labels in South East London,” he adds, nodding to the likes of On The Corner, Brokntoys, Rhythm Section and the shop’s in-house imprints West Friends and Cotch International.

As vinyl continues to grow in popularity, more options for pressing records are being established, which should help accommodate the rise in independent labels. A plant opened in Dublin last month and a new Australian factory is set to follow soon. Last year saw Jamaica’s Tuff Gong International return to pressing records, as well as plants opening in Brazil, South Korea, Berlin and more. There’s also been investment in new technologies, including more efficient pressing machinery, and services such as Qrates and Vinylize.it which are ideal for independent start-ups looking to keep costs down as they enter the vinyl fray, offering limited runs of just 100 copies. This is especially viable when coupled with online direct selling platforms such as Bandcamp, which paid out $270 million to a user base of predominantly independent labels and artists in 2017 while recording a 54 per cent growth in vinyl sales.

“I think the more options there are to press vinyl the better, as long as the quality is kept high,” says Perc Trax founder Perc. “If lower minimum production runs help labels get started with vinyl and allows them to steadily build up a vinyl buying audience then that is great.”

The quality of the music on records being produced in this independent production spike has been seen as a problem in some corners. Commenting on the rise in small-scale labels and distributors, Jason Spinks says there are “too many! A lot come and go, a lot you wouldn't know they were there before they're gone.”

He thinks talk of a vinyl resurgence is leading to some people entering the physical label realm with a naive outlook on the potential for risk as well as reward. “It's very tough and lots of labels are jostling for position,” he says. “It's healthy to a degree, but i think some people get into it thinking that the records will just sell as there's a vinyl boom, but get a sharp shock when things don't turn out as they thought.”

Tom Lea, founder of Local Action, thinks the idea that releases need to be on vinyl is unfair on artists, and can cause both the producer’s and label’s progress to stagnate if sales disappoint. “I don’t sign anything because I think it’ll sell, I sign it because I love the music, but pressing vinyl with an artist who probably doesn’t have the fanbase to sell it puts an unfair pressure on a release,” he says. “Chances are with a digital album, the most you’re going to lose is a few hundred quid if it doesn’t sell well. With a vinyl release you could be looking at an £800-£1000 loss, which is demotivating to the artist and label when those figures come in.” Perc offers the advice: “Remember that the format does not change the quality of the music. Releasing vinyl is not essential to your label being taken seriously and it will not instantly win your music more DJ support or help it reach a wider audience.”

Spinks supports this view, adding that an initial buzz around the rising levels of new labels in operation since Kristina Records opened in 2011 started reversing in 2015. Buyers are now becoming more picky, and are increasingly turning to second-hand wax in the hunt for obscurities, which the shop has begun to stock more of. “Part of this I think is because the market started to become really saturated with a lot of mediocre stuff,” says Spinks.

Spinks adds that although digging for rarities has always been a part of dance music culture over the years, it has “seemed to gain more traction through certain DJs, artists and labels, and the media fetishising over people’s record collections and their ‘setups’, which has become a bit tiresome and out of hand.” Last year, Ben UFO tweeted: “if ur hovering over the purchase button on a fancy £££ record on discogs consider buying the last ten records you [downloaded from file-sharing network Soulseek] instead”.

A rising interest in older records is reflected in second-hand online music marketplace Discogs recording an 18.8 per cent vinyl sales growth last year, with a total of 7.95 million units sold, of which 3.45 million were categorised as electronic. Similarly, various music publication postings covering expensive sales on Discogs, and one user compiling regular monthly reports, demonstrates sizable interest around the rarest records being sold.

My Mixmag colleague Sean Griffiths hit back at the overt fetishisation of vinyl in 2015 with a comment piece headlined Stop Worshipping Wax. And Perc agrees that obsession with the format can cause problems if people place more importance on it than the actual music, which can transcend into clubland. “I've seen people shout online for weeks about their upcoming all vinyl set and then when they get behind the decks they would struggle to mix two copies of the same record,” he says. In 2016 London party Tropical Waste poked fun at the purists, advertising a night with the header: “No vinyl all night long”.

In the short term, the impact of vinyl breaking back into the mainstream is clearly causing some problems for the underground. But it’s still early days and teething problems as the industries intersect is perhaps inevitable. The investment in new technological production developments coupled with a growing audience of independent thinkers with an appreciation for the form could be more beneficial down the line. We hope the tables turn.

Patrick Hinton is Mixmag's Digital Staff Writer, follow him on Twitter