Cover stars

Cover stars

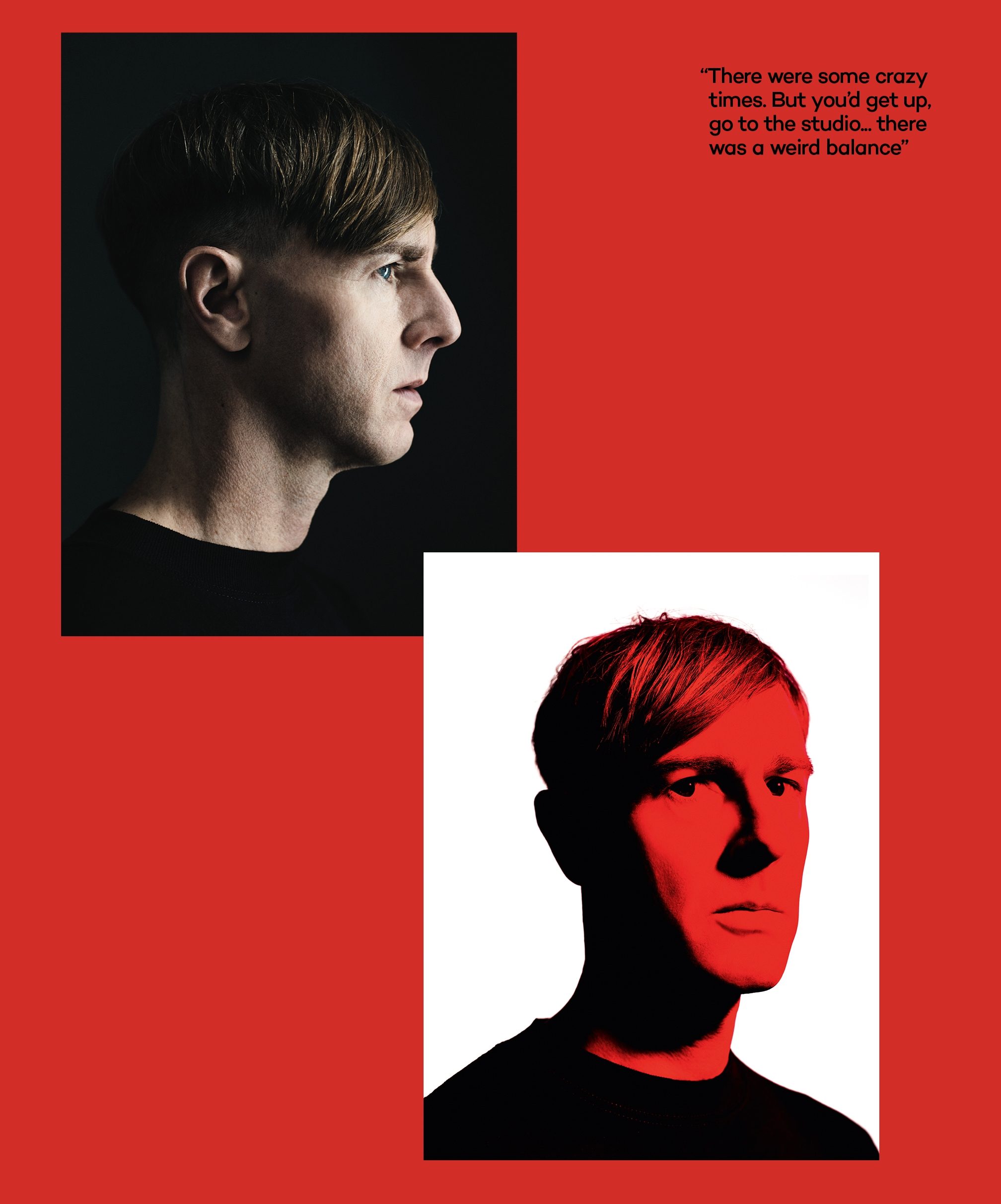

How Richie Hawtin transformed electronic music again and again and again

Richie Hawtin is always curious, always fearless, but always firmly connected to the dancefloor experience

Can you imagine Richie Hawtin as a Kiwi junglist? In a parallel universe he could easily have been, if a couple of things had gone differently. For one, before his parents emigrated from England to Canada, they were hoping to relocate to New Zealand. And second, there was a moment towards the end of the 90s where, sick of the direction techno was going, regularly partying at Metalheadz and making remixes for Mo’ Wax, he could quite easily have ended up moving to London and getting drawn into a very different scene.

As it is – of course – we know him as a Canada-raised, Detroit-connected techno overlord, one who is practically synonymous with the sound. He took hard and experimental electronic music international in the 1990s, led a spacier movement through the parties of Berlin and Ibiza through the 2000s, and has been an ambassador for techno’s further global expansion in the 2010s. His profile is up there with EDM and trance gigastars: perhaps only Carl Cox matches him in the techno world. At every turn, he’s pioneered new ways of playing, from early experiments with digital DJing to arena visuals to his new interactive audiovisual live album ‘CLOSE Combined’: perhaps the first true smartphone album, released as an app and allowing the user to view in detail what he’s doing, and to deconstruct his set in real time, isolating channels and instruments.

But three decades into the scene he dived into in his teens, he clearly hasn’t lost his grasp of the basics. In the club space set up for Mixmag’s BUDX event in Paris, packed with an audience of party people mostly under half his age, there’s no high-tech presentation, but Hawtin looks right at home in the booth. He walks up holding a sake and watches, smiling appreciatively, as Kevin Saunderson finishes his set – the slender Hawtin looking even more elfin than usual next to the hulking former American footballer as they embrace during Kevin’s final tune, before Richie sets about his digital DJ controller. It’s hardly trad: he doesn’t use any vinyl-style mixing or pitch control, instead concentrating on piecing ready-synced tracks and DJ tools together on the six channels of his own MODEL 1 mixer. But although the cutting, fading, EQing, reversing and layering of loops are done with non-standard tools, it’s recognisably DJing in the old-fashioned sense: organic, authentic, the crowd and the DJ feeding off each other. And it’s a reminder that despite all the tech, at heart Richie’s performance is about bringing joy to the dancefloor.

The next day we meet at his hotel. He’s staying at a five-star 1920s gaff just yards from the Arc de Triomphe, a place so old-school you could imagine Grace Kelly or David Niven stepping out of the lifts. It’s gloriously incongruous for someone whose image is so futurist – though Richie hastens to point out it was booked as a surprise treat for his wife. Slightly hungover, with dark circles under his eyes, he’s dressed in a classic all-black-everything techno outfit with frayed jeans and battered boots, and giggling at how discombobulating the grand surroundings are. But as soon as we get into talking about the gig and his life in general, he’s back to full energy levels, his conversation as full of quick shifts and gradually developing themes as his DJing. His rhetorical style is something to behold – though he has that classic Canadian soft, inquisitive tone, and is never bombastic, there’s a torrent of words without stumbling or hesitation: sometimes driving home a message on favourite themes, like a politician or CEO delivering an address, but just as often exploring an idea or question in fine detail as he goes, as if thinking about it for the first time.

This combination of inquisitiveness and confidence was instilled in him at an early age. He grew up with his parents and brother Matthew in north Oxfordshire until he was nine. The Hawtin family were – and still are – very close. He describes his parents as “really beautifully normal. They’re not like hippyish or bohemian, they’re just open-minded... my dad was always an introvert who felt really connected to electronics and music – maybe that also spurred my mum and dad to go off [abroad]: the curiosity of what’s beyond the UK, this island and that mentality with things like Thatcherism coming.” It was with this sense of curiosity and adventure that his dad sought technology jobs elsewhere in the world, and in 1979, just as Margaret Thatcher was elected, they headed to Canada. It was a leap of faith. “They had [originally] agreed to go to New Zealand,” says Richie, “and at the last minute, they got cold feet because it was too far away from family – then immediately they regretted that and they said, ‘OK, wherever we get the chance to go next, we’re going’, and that happened to be Windsor, Ontario.”

Once in Canada they felt overwhelmed. “Big cars, big streets, all the wires overhead, Detroit looming on the horizon, it was in the winter so everything was freezing, we all got sick... Matthew and I felt like aliens, walking, talking differently. But it was really the beginning of a whole new adventure.” Again and again he returns to the theme of the family as a unit, encouraging each other in their quirky obsessions. Matthew pursued visual art from a very early age, but Richie, like their dad, “loved to tinker with technology,” initially trying to emulate his creative first love: zombie films and special FX. Trying to make animations “led me into programming, sitting by myself, learning to take control of this kind of virtual space, making games, communicating with people on early bulletin board systems.”

Music began to take over, though. Electronic sound was there all along thanks to his parents’ collection of Kraftwerk, Tomita and other early synth records. But from the first time Richie went out in his teens, he came to love the 80s mix of goth, new romantic, industrial, disco and funk in Windsor’s clubs – and just as much, the fact the crowd was “black, white, gay, straight – you know, everyone – with make-up and androgynous looks and resale clothing. There was a lot of experimentation in that.” In 1986, when the 16-year-old Richie started going out in Detroit, this was redoubled. Seeing Juan Atkins and Derrick May mash together early house and techno with a range of other sounds, he felt like he was “in the presence of mad scientists”, and he religiously followed DJs like Blake Baxter, Ken Collier and Scott Gordon – who would become his mentor at The Shelter – and listened to Jeff Mills (then The Wizard) on the radio each night.

He bought records, he DJed, he revelled in the energy of a scene that, bar a little weed being smoked in corners, generally wasn’t drug fuelled (he was flabbergasted when someone offered him coke at The Shelter, and told his mum when he got home), yet would keep powering through to six or eight in the morning. As in Windsor, it felt like “a freak scene... people who didn’t fit in anywhere else, all finding themselves together in this black room with a strobe.”

Then, in 1989 he met John Acquaviva and Daniel Bell, who were already accumulating recording kit: “909, 303, 808, 101, Pro 1s, you know, sync in a sequencer, one, two, three notes, play, and suddenly techno was coming out of the speakers in front of you!”. Within a year the trio had made ‘Technarchy’ as Cybersonik, a still-huge fusion of Detroit funk and pure industrial fury, which was picked up worldwide, even by proto hardcore DJs like Fabio and Grooverider in the UK. At the same time, Richie was making deeper, bleepy techno under his F.U.S.E. alias. They dreamed of releasing on Derrick May’s Transmat or Juan Atkins’s Metroplex, but unable to get the attention of their idols, they founded Plus 8 instead.

Another year on and the “tinkering” had turned serious: Richie was playing internationally, and Plus 8 was a real business. The European connections came thick and fast: “The UK first, then Italy and Rotterdam and Amsterdam and Hamburg and Berlin and Frankfurt – that was Sven [Väth] of course, we’d met at a New Music Seminar in 1990...” This was part ambition, part grand curiosity about the wider musical world: “We’d always loved Mute Records, Nitzer Ebb, Front 242, and people like Speedy J were sending us music from Netherlands... so I don’t know if we were globally focused in the sense of ambition, or just globally fascinated.” It was hectic, though. Richie was running the label with John all week, completely DIY-style, taking orders, sending out records, crossing the US/Canada border multiple times a week as the pressing plants and warehouses were in Detroit, then heading to Europe to play ever bigger and wilder raves every weekend. He connected with WARP, which placed the F.U.S.E. album (with artwork by Matthew and recently re-released on Vinyl Factory) in a wider context as part of their Artificial Intelligence series of “listening techno”, putting him in on the ground floor of what would become the IDM movement, and with Novamute, who would release his Plastikman guise.

The 90s went on like this, John and Richie having no clue whether techno would last, “never knowing if it’d go more than another year!” Obviously it didn’t die, but frustration set in. Techno itself got harder, more rigid and more macho: “So many records, so many of them mediocre”. The work was hard, too, and Richie became unable to go to Detroit after being temporarily banned from the US in 1996 – it was a Catch-22 situation because he’d been DJing with a work permit, even though at the time work permits weren’t even issued for DJs. He’d never been a natural at DJing to thousands, anyway – the first time he played to 5,000 at Berlin’s Mayday, “I was horrified!” Eventually, though, “it lost its lustre, it had become like any other business and it just wasn’t really fun any more”, so he and John closed Plus 8 in 1998. It was at this point he considered moving to London, and there was a very real possibility that he could’ve left techno behind. But instead, he founded M-nus, the name symbolic of a stripping away of everything unnecessary from music, and from life.

The musical shift wasn’t instant, but it was major. Listen to 1999’s ‘Decks, EFX & 909’ mix album – still hard and pummelling – then the slower, funkier, moodier grooves of 2001’s ‘DE9’ and you can hear the mature Hawtin sound forming in front of you. ‘DE9’ represents the sounds of smaller clubs and back rooms, particularly in Berlin, a scene that was a little more out-there and a lot less male-dominated, where Richie was connecting with glitchy musical misfits like Ricardo Villalobos. Mixed live with digital controllers from tiny sections of over 100 tracks, DE9 also marks his transition fully into the digital realm –

he and John Acquaviva were involved at the time with the Final Scratch controller – and they correctly predicted the rise of this kind of digital track manipulation.

In 2005 he moved to Berlin full time, just as ‘MNML’ was kicking off across Europe. The M-nus collective he remembers as “a great gang of people experimenting, playing and just hanging out; it was a real hotbed of creativity and it was very adventurous musically and socially”. Ibiza parties and spots like Bar25 and Der Visionaere in Berlin were notoriously decadent – “a different time to the naive days of Detroit in the late eighties!” – and DJ sessions would go on for two, three days at a time. Yet at the same time it was run with the same discipline as Plus 8 was. “The stories are true,” he laughs; “there were some really, really crazy times. But between that, during the week, you’d get up, go the gym in the morning, go to the studio, go for a swim or something, and I’d always take a month, two, maybe three off at the start of the year, and there was some kind of weird balance in that.”

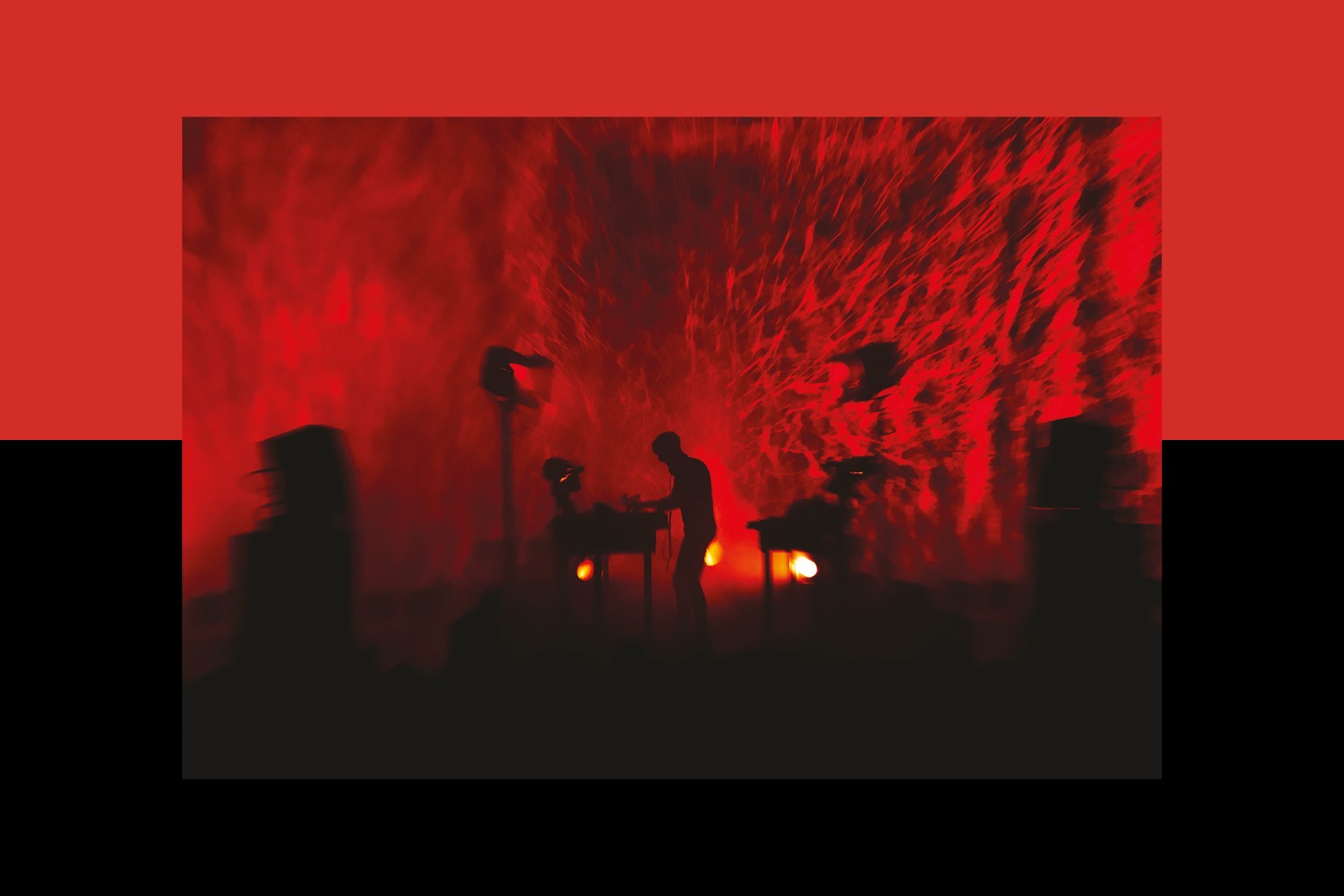

And M-nus really was a well-oiled machine, pumping out global club anthems, creating ever bigger, high-tech spectacles, culminating in the Contakt event series where he, Magda, Troy Pierce, Marc Houle, Gaiser and Heartthrob would perform live using a mysterious glowing cube, all framed in wonderfully preposterous sci-fi language and imagery. It was the peak, but also essentially the end of the collective. All the participants were on their own trajectories, and Richie was feeling once again that he needed to move on. He revived the Plastikman alias for full live shows in the early 2010s, but it’s really been DJing, and the technical and aesthetic themes he began with ‘Decks, EFX & 909’, ‘DE’9 and 2005’s ‘DE9 Transitions’, that have been his primary concern since. Which brings us to ‘CLOSE Combined’: live instruments and multi-channel digital DJing for big arenas, with the process opened up for the fans to see in exacting detail.

The motives behind it are multiple. Obviously there’s his love of technology and “tinkering” – and he’s still dreaming big, for example of an AI that could “suggest motifs by other musicians that might fit into what I’m playing in real time, and put me in direct contact with the musician that made it in, say, Buenos Aries, as I’m playing it for us to interact.” But it’s also partly a shield. Though of course he’s used to big crowds now, the shy nerd who felt alien and exposed is still there. So whether its his actual family (he still works with Matthew, and their parents will still come to his shows), the creative and business teams he builds, his consistently smart graphic branding, the intricate tech set-ups on stage, or even his spontaneous manifestos as he’s talking, he’s always building structures to protect himself. He’s driven to reach bigger and bigger audiences by a natural adventurous spirit, but personally he’s most comfortable in small clubs like those he started in and keeps returning to. It’s as if technological innovation works to protect him as an individual from the spotlight’s glare.

These kind of tensions, though, seem to keep him going. On the one hand, Richie accepts that “techno is a business now,” and he’s acutely aware of the risk of the global scene repeating what happened in Europe in the late 90s: “bigger venues, shorter sets, not enough variety... DJs out to milk it for all it’s worth, make their money and get out.” But on the other, as well as being palpably excited by technological progress, he means it when he says “this is a lifestyle, a culture, you don’t just plug in and check in and do some sets for a couple years and check out. This is something more.” Faced with Trump, authoritarianism and the “tragedy” of Brexit – and also by the homogenisation of techno crowds – he says, “It’s time we need to speak out more about what we believe. This culture, techno culture, came out of places that were for diverse, strange, experimentally minded people who didn’t fit in elsewhere.”

“We were the nerds,” he concludes; “the goths, the guys in make-up, black, white, gay, straight, brought together by music and parties, and we need to remember that and let people know that. And we need to take responsibility for what we do, too. We know that this DJ lifestyle is wasteful, so me and my team carbon offset all our flights. When we announced it in 2007 nobody seemed interested – but maybe it’s time now to start talking about it more. Maybe people are ready to listen now. I hope so.” As ever, it’s when he talks about change, or progression, or evolution, that he’s at his most fired up. It’s impossible not to wonder where Richie Hawtin might take electronic music next.

Joe Muggs is a freelance music journalist and regular contributor to Mixmag. Follow him on Twitter

Read this next!

Cover Star Selects: Richie Hawtin

Playing differently: Richie Hawtin and his DJ super-team

Watch: RIiche Hawtin Mixmag Live @ Output NYC