Scene reports

Scene reports

"Evil bastards!": Why a tabloid storm won't crush Glasgow's famous 'afters' scene

Fake news forced a secretive late-night club to shut - but Glasgow's longstanding after hours culture isn't going anywhere

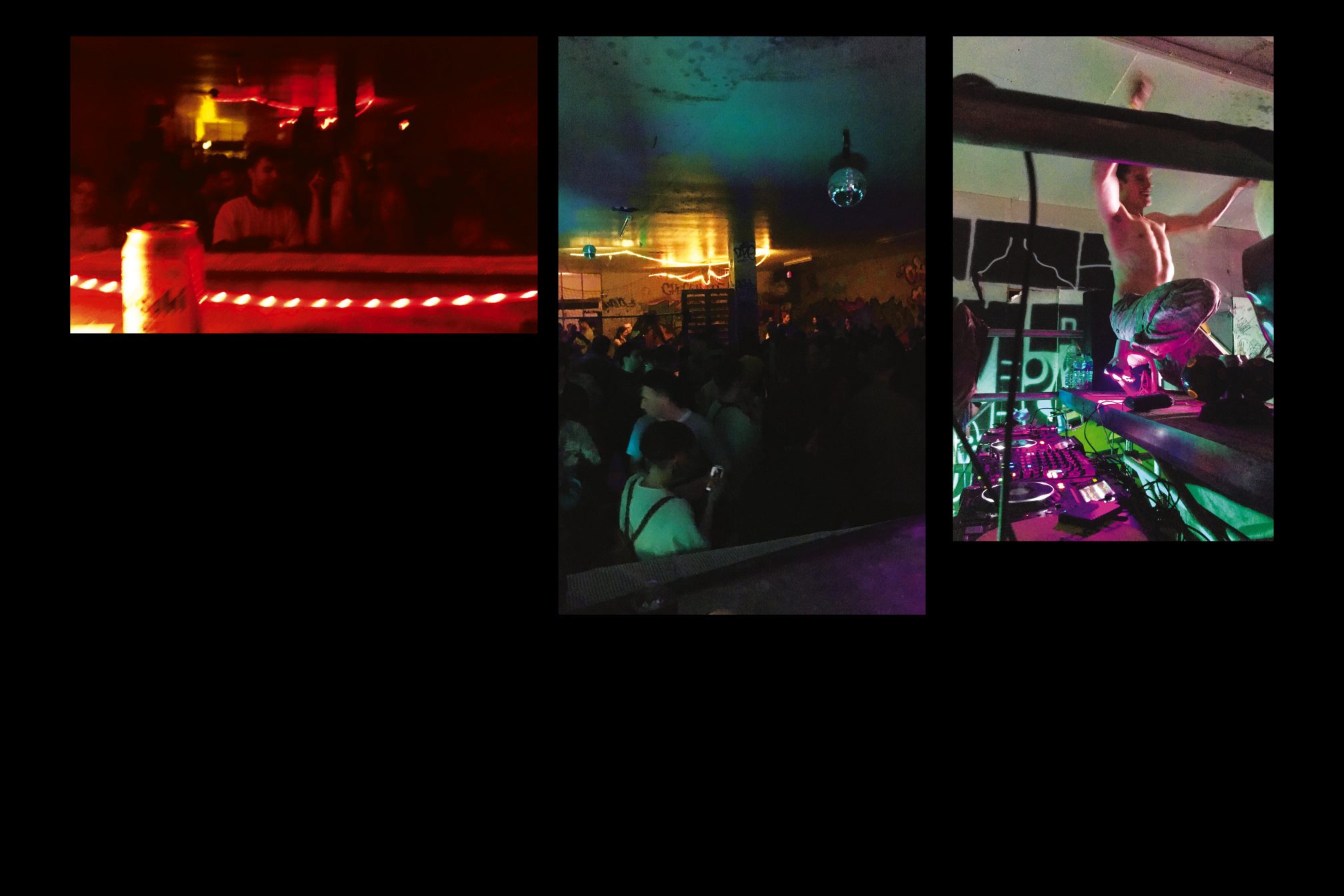

Picture a grubby red sandstone tower on the south side of Glasgow’s River Clyde, disused and dilapidated, surrounded by empty car parks, overgrown scrub and warehousing space. It’s just past 3:AM, and all the clubs in the city whose names you might know are closed.

“You walked in and there was a staircase, then up two floors was a little window where a suggested donation was made,” says John Markey, nursing a mid-week pint in a pub on the Southside. “A lot of graffiti artists were involved so it had an art space vibe. On your right as you went into the main room there was a chill-out area with cargo netting and lots of sofas. At the back was a DJ area with a huge screen behind the decks; rumour has it it went missing from a famous rapper’s tour of Glasgow. It was really impressive. There was a well-stocked bar that would do cocktails. They served Buckfast, obviously, and bottles of water too. The best thing about it was that there was an actual functioning bathroom. At one stage there was even a toilet attendant!”

“On the way up the stairs there were mannequins dressed in bowling shirts and beautiful bits of graffiti,” adds Oliver Melling, Markey’s friend and DJ partner, perched on a high stool as the football results come in behind him. “It wasn’t ramshackle, there was a respect between each piece – a bicycle wheel hanging down above you, traffic cones which had been graffed, strings of LEDs. You got the sense that this place hadn’t happened overnight. There were so many layers of expression because tiers of people were involved over a long period of time, passing it on to the next person, and the next person…”

Checkmate – the club to which they’re referring – came to an end in June 2019. The manner of its ending had fairly traumatic consequences for Markey and Melling, as it happened immediately after the pair, along with a friend, were exposed as the supposed ‘Men Behind the Mayhem’ in Scottish newspaper The Sunday Mail (no relation to The Daily Mail), amid an investigation into the city’s famous ‘afters’ scene.

Any clubber in the city whose focus is on quality music will be aware that the ‘Glasgow afters’ is a widely known culture of unlicensed warehouse afterparties which occur – as all those who we spoke to agreed – as a direct result of the city’s licensing laws only allowing clubs to stay open until 3:AM (a recent extension until 4:AM has been agreed for certain venues).

Read this next: Glasgow's Sub Club is one of the best rave experiences on the planet

While early closing may help drive the internationally renowned atmosphere in Glasgow’s clubs, with the narrow window between pub and club closing inspiring a particularly furious period of dancing, it also feeds the demand for a carry-on. And, as any resident of Berlin, London or Amsterdam will tell you, the world doesn’t cave in when you hand out all-night licenses.

Markey and Melling are smart, enthusiastic and articulate young guys; Markey a dryly humorous Irishman with long black hair, Melling a tall Scot with boundless enthusiasm. Together they are We Should Hang Out More, with DJ residencies in the city’s Sub Club and Berkeley Suite and a joint production career. Their last EP was named ‘Tradeston Knights’, a reference to Checkmate’s name and location, and it fused Chicago house to a disco groove in exciting fashion – much like their club sets. Widely regarded as being among the city’s finest young electronic talent, they believed the newspaper exposé had brought their professional lives to an end on the Monday after it happened. By the Tuesday, however, they’d been offered a deal by the booking agency which reps Late Nite Tuff Guy.

”We were playing at Checkmate the night the story broke,” says Markey. “We live near each other so we were sharing a taxi back and our phones started going mental at 7:AM as people got the news.”

The newspaper had sent an undercover reporter to a Checkmate party, and the story led with photos of Markey, Melling and their friend Daniel Cameron, all linked to the club via a Facebook group. “We should declare here: there was a private Facebook group,” explains Markey. “We got told who was playing and we said [to the group] who was playing. We didn’t organise it, we didn’t rent the building… we were the resident DJs and we played at the show. But you get the paper, you open it up, there are massive pictures of you and your friend, and you’re essentially painted as villains. It was horrible. Genuinely horrible. I’m blessed to have never really had any mental health problems in my life, but the two days that followed were the darkest of my life. We both work part-time jobs to help support our music and I was utterly convinced that my career was finished [Markey has a doctorate and works in adult education]. I was thinking of my family: this thing implied quite heavily that we were some sort of drug kingpins running an underground empire.”

Melling nods in support. “I’m similar to a lot of people right now in that I work a bunch of jobs,” he says. “With each of these, they had to have a meeting and come back to me; a sort of staggered resolution. Part of me was thinking, ‘should I bravado it, should I swagger it?’ And then I thought that might be attracting attention I didn’t want.”

“The support we got from the music scene in Glasgow was incredible, though,” says Markey, pointing to an array of DJs, labels, venue bosses, clubbers and international touring DJs and their agents who messaged or shared social media posts in support. “It’s worth mentioning the public reaction as well. The newspaper was clearly trying to drum up outrage among a certain demographic – forty or fifty-plus – but there were people of that age commenting, ‘I did this in the 80s!’ This is nothing new.”

“I did get absolutely trolled for calling myself a ‘groove mechanic’ on my Facebook page, though,” admits Melling, breaking the sombre mood. “Which is fair enough, really.”

“And the line in the article that says the journalist attended one of these events and ‘there was no sign of trouble or bad behaviour and the atmosphere was relaxed and carefree’?” chimes in Markey with a head-shaking laugh. “Well, fuckin’ lock the people who go to [these parties] up! Evil bastards!”

After making an IPSO complaint, Markey was offered a right of reply in which he addressed the main thrust of the piece. “To be clear, I am not involved in any way with illegal drugs,” he wrote. “Drugs are an endemic and long-standing global issue. If drugs cannot be kept out of prisons or the Houses of Parliament, it will clearly be difficult to keep them out of music venues.”

Possibly thanks to social media, Glasgow’s afters scene has exploded in the last couple of years; we were told up to seven parties operated in the city during any one month, although this sharply tailed off following the exposé. Markey isn’t joking about how long the afters have been going; in years past, clubs like Desert Storm and The Unit operated in derelict spaces around Glasgow, and have since passed into underground legend.

Read this next: Glasgow tourism bosses want the city to promote techno tours

“The first time I went to an afters was maybe 2003, and it had already been going for five, ten years before that,” says sometime promoter Simon [not his real name], who DJed at Checkmate before We Should Hang Out More began their residency in 2018. “At the peak, the most I’ve heard of in one month was about nine or ten parties. The venues are places large enough to house about 300 people, not near any houses, not on a busy main road, and walkable from the city centre clubs. Normally they’re cheap rents, somewhere that’s a bit run-down without many facilities; they vary from old warehouses to ex-factories to workshops. It’s exactly what you would think it would be.”

For its final two or three years, Ben [also not his real name] and a friend ‘inherited’ The Unit, a railway arch near Central Station. “Network Rail kicked us out. That used to be one of the only ones, and back then it was really hush. Turn the corner, make sure you’re in those gates as fast as possible, don’t get taxis to the door. Now, in comparison, people are desensitised to keeping it under wraps. These days it’s quite a common thing in Glasgow.” He’s now one of a team of four at another afterparty.

“[What’s been said about Glasgow’s afters] couldn’t be further from the truth,” he continues. “It’s just a nice place to hang out; for the whole six years we’ve been there we’ve never had an incident with anyone full of drugs or causing trouble. Whereas clubs in town – the commercial clubs that the majority of the population go to – probably have a lot more drugs and trouble and fighting.”

Throughout these interviews, the same points keep coming up: how security is hired at most venues, certainly at Checkmate; how the crowd is far more aware and self-policing at afters, particularly in terms of trouble and the safety of others; how these places are crucial in terms of allowing local DJs to grow and flourish with long sets, whereas regular clubs offer them space for just an hour’s warm-up before the inevitable international headliner appears (it’s not unknown for some big names to accept a spur-of-the-moment invite to play a party like Checkmate.) Ben is keen to point out that sets by young DJs at his party are recorded and made available on SoundCloud.

Also, crucially, many afters are places where queer crowds can be themselves, away from the mainstream. Although the people we spoke to for this piece were all white and male, there are women and LGBTQ people involved in the scene; their choice not to speak to us, we’re told, is about protecting their community as much as their spaces. In terms of diversity, Markey also mentions the people from across the globe he has met at Checkmate.

Every afters has its own style, its own sound and its own community. “Some people have been a bit too blasé about unwanted attention,” says Ben. “There was a Vice documentary, and we were reluctant to be involved in that at the time – but I think now is the right time to talk. Afterparties have been getting some really negative press, and it shouldn’t be that way.”

The problem, of course, is the question of legality (or lack thereof) and the legitimate questions this raises about safety, security and policing – despite some vague arguments that an afters is essentially a private party (and Ben points out their venue has actually had fire safety checks). “None of these people are lawyers, and there’s no proper knowledge [as to] where the legalities lie,” says Simon, “but to me the thing is illegal because there’s a bar. That’s the boring side for me, though – there’s no point in trying to shave off responsibility. I’m more interested in the art of it; in what you can make out of those spaces that you can’t make elsewhere.”

Read this next: Tiny but fierce: How La Cheetah became a Glasgow clubbing institution

Another point all are in agreement on is this: if Glasgow wants to wipe out its afters, which is not a passing trend but a decades-long cultural phenomenon caused by the geography and licensing rules of the city – all it needs to do is extend its club licensing hours until at least 7:AM. After all, legitimate all-night parties mean more tax income for the city. Yet those involved would miss them as they are now.

“The musical education I got didn’t come between the hours of 10:PM and 3:AM,” says Simon. “It came at those afters, those flat parties; it came via sitting with somebody who knows a certain niche of music and is itching to tell you, and you can talk because you’re not in a club. The afters is a weird half-space between a club and a rave and somebody’s gaff. A club’s not actually a great place to talk about anything; the afters opens up those opportunities.”

There’s an uncomfortable irony in events like these being stigmatised, without any attempt to understand the overwhelming cultural reasons for them happening, when the artist Jeremy Deller is making BBC documentaries about the free party scene of the early 1990s and the film Beats is being acclaimed for its presentation of the same era in Scotland. Kieran Hurley, the Glasgow-based writer of both the play and the film version of Beats, has a young family and no involvement in the afters scene, but he worked ripping club tickets at Glasgow’s Arches (where Beats was rehearsed and first staged) and campaigned to keep the venue open.

Read this next: Raveheart: How house music exploded in Scotland

His thoughts on the free party scene of the 90s feel like they can be applied to the afters scene of today: “For me, rave was a generation responding to a human need for collectivity and communal experience at a moment in history when that was being denied in favour of a top-down culture of rampant individualism. We’ve had nearly forty years of fairly unreconstituted Thatcherism in Britain, and those little tremors, those cultural pushes against stuff matter. The need for young people to experience a communal claiming of space through celebration of life on a dancefloor never really goes away.”

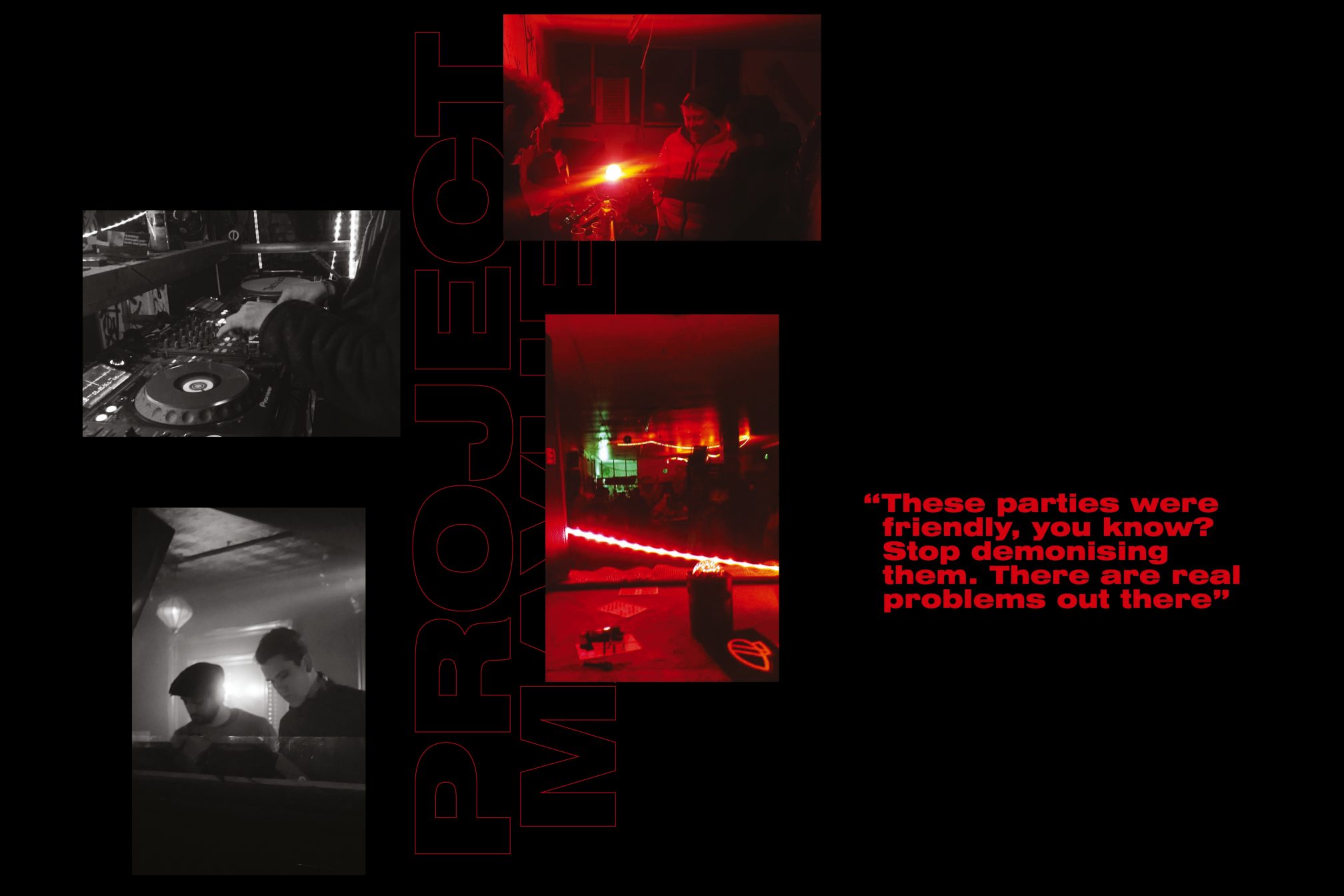

“People aren’t doing this for money,” says Markey, drawing our conversation to a close. The pair want to leave this episode behind, but only once they’ve said their piece. “These people are doing it because they love throwing parties, it’s a huge part of their lives. And just like Glasgow, these parties were fuckin’ friendly, you know? Stop demonising them, there’s real problems out there. The planet is dying, people don’t have enough money to eat, they’re literally starving in their homes. Those are the issues. But people drinking and having fun in a building…?

“Checkmate’s shut, it won’t reopen,” he concludes. “We have incredibly fond memories, it was a wonderful place. But don’t worry, there’ll be another vault opening somewhere – and maybe we’ll play in it, because we really like DJing at parties. That’s just what we do.”

Their story mirrors all those who have given Glasgow its mighty international reputation as a place to play and hear electronic music. In an effort to reclaim it, Markey tells us, We Should Hang Out More’s next EP will be named ‘Behind The Mayhem’.

David Pollock is a freelance writer, follow him on Twitter

Read this next: Get the best of Mixmag direct to your Facebook DMs