Features

Features

The lesser told story of broken beat, the enigmatic sound that is yet to ‘break’ the mainstream

As broken beat slowly returns to the collective consciousness following years in the shadows, Jamaal Johnson takes a look at the lesser-told story of the West London-born subculture, chatting with scene stalwart IG Culture and the up-and-coming Donsurf. They discuss the sound and why it has remained underground, as well as looking at the reasons for its resurgence, considering the changes we might see with the newest wave of broken beat

Broken beat, or bruk, is a term you might be long familiar with, or only have come across recently. The sound is best recognised as a dance music genre landing between 120 and 130 BPM, containing elements of Latin and African rhythms, as well as borrowing heavily from jungle, hip hop, and Caribbean soundsystem culture. Bruk first saw light towards the end of the ‘90s, and after a period of inactivity, the sound is slowly but surely regaining traction in the underground dance music scene, with a number of DJs and producers using the tag; It’s been name-dropped in our recent features with Musclecars, Errol and Rohan Rakhit. You might have found the term in track descriptions on Bandcamp or Mixcloud alongside a selection of other tags, reading something like “House, Garage, UK Funky, Bruk”.

Wherever you’ve seen it, broken beat is undoubtedly back. While still underground, the sound is becoming more widely played and produced. A Bandcamp search of ‘broken beat’ reveals 6000+ tracks claiming the tag, with over 700 of these tracks released in 2024 alone, with input from Berlin, Sydney, Baltimore, Madrid, and of course London, among a host of other places. Boosted by the internet, the sound's fluid identity and global influences have seen it go from strength to strength since the genre’s re-emergence in the late 2010s. So what actually is broken beat?

Depending on who you speak to, descriptions of the genre range from “chill future jazz” to “bass-bin rattlers”. For some, the sound constitutes an interesting niche of jazz-based dance music, distinguished by its atonal chords and expansive keys licks. Others might describe the genre to you as something far heavier and closer to UK garage, characterised by aggressive basslines, syncopated and splashy percussion, punchy irregular snares, and Patois vocals. Then there’s the term broken, through which a number of conflicting (and somewhat irrelevant) connotations spring to mind .. breakbeat, breakdance ….

The sound is best characterised by a snare hit that lands slightly before the fourth beat, creating this sense of perpetual motion and jerkiness. This is what makes the sound so addictive for many, but also divisive, with certain people struggling to lock into the groove. However aside from the snare (even that isn’t crucial), the sound can contain all sorts of Latin percussion, differing kick patterns, (which range from four-to-the-floor to more garagey configurations), and a range of composition styles, some including vocalists, some extremely dark and just involving bass and drums, and some which channel a whole array of live instrumentation.

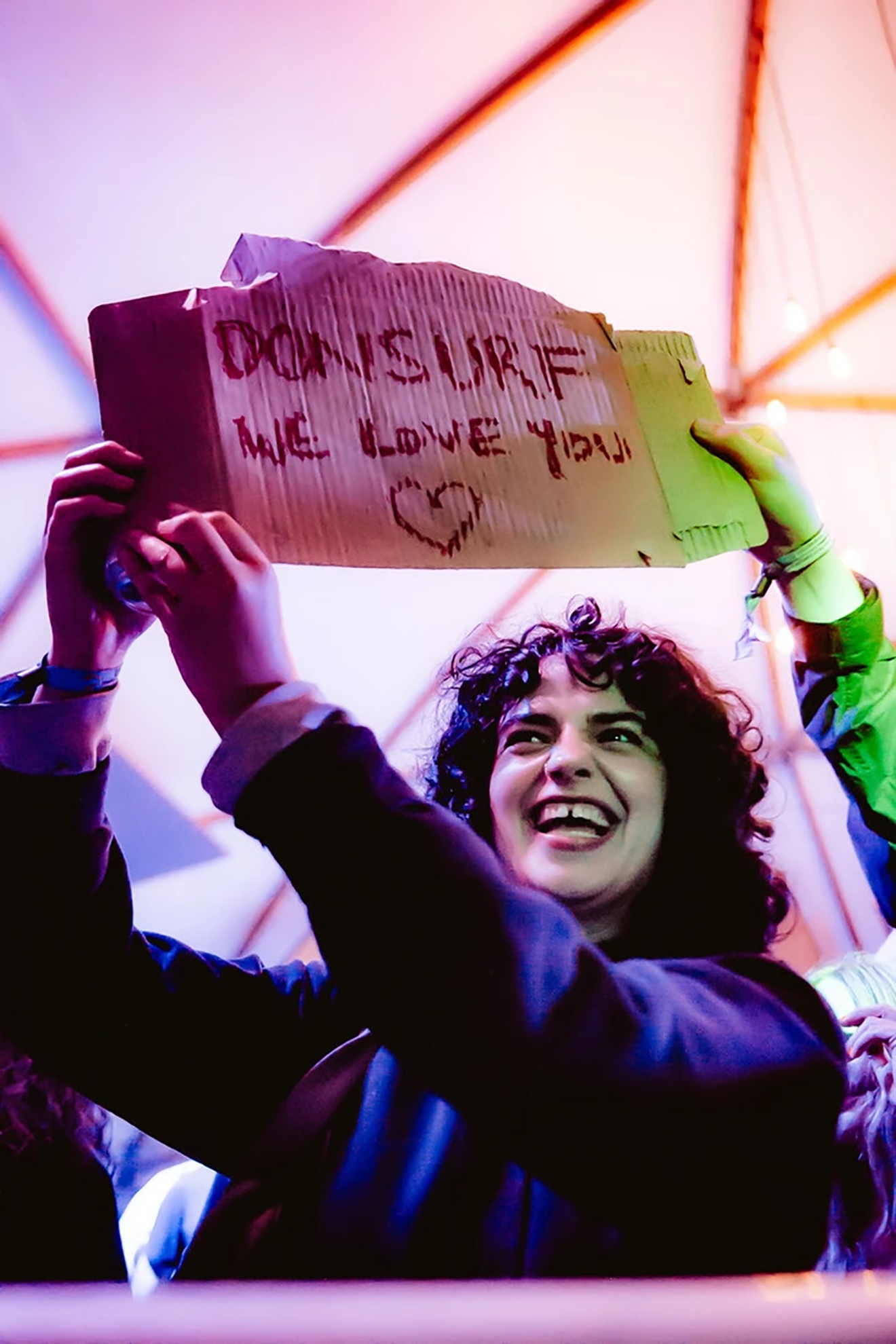

A good person to ask about the sound is Donsurf, the man with a whole host of recent broken beat releases on labels such as Dance Regular, EC2A and Kultura Collective, as well as a number of independent releases. He’s described by broken beat stalwart IG Culture as a “new bruk soldier”. When asked what it is about bruk that sounds so good, he tells me, “Whenever I’m in the club, it’s that ‘pop’ of the snares, the polyrhythms going on that sort of gains my interest. It’s a lot more interesting to listen to than 4/4. There’s also a big multicultural influence on the sound, like Afro-Latin, Afro-Cuban influences. A lot of samba rhythms in there too, like the clave matches up with snare patterns in broken beat a lot of the time. It’s the same with Afro grooves as well - I mean if you listen to an old Fela Kuti or a Tony Allen drum beat, those patterns are often exactly the same as a broken beat groove.”

Read this next: RIP Tony Allen: The self-taught drummer who became the best in the world

IG Culture highlights this versatility within bruk’s sound, saying, “Take for example [Sheffield-based artist] Xtra Brux - he goes all the way to the dark side. But then you've got artists like myself, who can do something dutty but then you might hear a soulful element in there, or a jazzy element. But there's also grime elements to other tracks - to capture the whole thing, it goes from the jazz to the dirt.”

This versatility is both the genre’s biggest strength, and perhaps in the eyes of the industry its biggest weakness — with a sound so broadly defined, the casual listener has often struggled to pick up on what they’re listening to, unlike let’s say garage (with its distinctive swung hi-hats) or jungle (everybody knows the Amen break), which have such clearly defined signatures. To some it just sounds too intricate, there’s too much going on, and they prefer the safety and comfort represented by 4/4 and its more limited rhythmic capabilities … I have to recount here a story of playing some bruk out in New York, and a slightly overzealous punter coming to tell me it was ‘out of sync’, despite only one track playing.

Anyway, for a number of reasons, bruk has always remained part of the underground. It never really had a seminal project or artist which became a household name and cemented the genre into the collective psyche, failing to enter far into the charts or the public eye, contrasting with the commercial success of some of the other dance music sounds that emerged at the time. As IG Culture tells me, “We never had our ‘Are You Gonna Bang Doe?’”, referring to the UK funky hit which took the nation by storm in late 2010 (although it brought a short-lived mainstream lens to the genre which, retrospectively, might have done more harm than good.)

The track that came closest was probably the transcendental Bugz In The Attic remix of the Amy Winehouse hit ‘In My Bed’, with IG saying, “It kind of crossed genres, where if you was into garage or house, or funky, you could get into that.” Donsurf backs this up, saying, “The first broken tune I heard was ‘In My Bed’ Bugz In The Attic, banging it out when I was in college without knowing what it was.” Despite that track and a couple of other Bugz In The Attic hits garnering a lot of traction in the clubs, the genre never seemed to stray too far from its spiritual home of West London and Plastic People. This is despite CoOp (the seminal bruk night) being continuously name-dropped as one of the most influential nights on UK dance music, with countless DJs and producers (Apple, Errol, Alexander Nut, Femi Adeyemi, EVM128, Shy One, T. Williams, the list goes on) recalling the effect that attending those events had on them and their music. It seems almost unfathomable that something so revered by so many almost slipped away from the public eye completely.

To try and begin to explain this, IG tells me, “It was real. It was underground in the truest sense of the word.”

THE BEGINNING

The ’90s had seen a number of genres crop up in the UK, following on from the underground then commercial success of jungle and drum ’n' bass. Broken beat emerged later, as one of the lesser known dance music genres, stylistically very different but borrowing many elements from the aforementioned sounds. It stemmed from producers trying their hands at new rhythms, inspired by the likes of Masters at Work (particularly ‘The Nervous Track’), jazz fusion, soul and Afro-Latin rhythms, and Caribbean soundsystem culture. This newfound syncopated sound began to pave the route away from four-to-the-floor dance music, rising out of West London and weaving a new chapter in the area’s rich musical tapestry, adding to the legacies created by seminal musicians such as 4hero and Jamiroquai, as well as the legendary Notting Hill Carnival. Like all great discoveries, it emerged through risk-taking and innovation, from a producer and a label willing to break the mould and try something new.

The origins of the genre are often contested, and due to its transcendental nature it’s difficult to pinpoint a definitive start, but 1997’s ‘Groove Now/New Goya’ 12” by New Sector Movements (one of IG Culture’s many aliases) is generally credited as the first track that can be given the broken beat tag. Coming from a hip hop background, having spent years performing and producing with Dodge City Productions, IG had been clear to the label, People, on one thing: “I don't really do house, I don't want to do house. And he [Mike Slocombe, label manager] said, ‘Well try and do something in between.’” This led IG to experiment with this sort of ‘broken’ sound, driven by snares and an off-kilter beat, inspired by motifs and rhythms from across the globe, as well as the jazz fusion era of Herbie Hancock and George Duke. It wasn’t an explicitly new genre immediately, with IG saying himself and singer Bembe Segue “never really narrowed it down to ‘Oh, we're making a new genre’,”. However “we both used to say the groove is changing, the groove is changing. That was just like a mantra we had between us - we didn't say, right, we're gonna make a new genre.”

Read this next: How your favourite genre got its name

This late ‘90s period saw a variety of producers try their hand at this new approach, with the likes of Dego, Domu and Mark Force adding their own flavour to the fledgling sound, coming from drum ’n’ bass and jungle backgrounds. Then you had the influential Afronaut and the late Phil Asher who came from house music sensibilities, and sound engineer and record collector Daz-I-Kue who was dealing in disco, hip hop and boogie. Piano player Kaidi Tatham began to introduce the expansive keyboard licks and jazz fusion sounds that have become synonymous with bruk, and for the early years there was a non-stop flow of music, community and experimentation, creating a sound that was hard to classify; it was high-energy, underground, yet building momentum.

This community was key to the formation of the sound, born out of West London and centred around record distributor Goya Music, which provided the platform, finances and strategic home of the genre, based in the same building as IG, and Dego’s 2000Black. This saw a number of individuals come together, with seminal broken beat supergroup Bugz In The Attic emerging.

As well as a huge roster of producers, which included the likes of Seiji and Mark Force, the group gained recognition through working with a number of influential soul and R&B singers, including: jazz-funk royalty Vanessa Freeman, percussionist composer and singer Bembe Segue, Philadelphian house vocalist Lady Alma, and MC and spoken word vocalist LyricL to create a specific sound unique to the bruk scene, described by writer Emma Warren as, “fusing razor-creased electronics with caramel-smooth soul.”

This was the group that arguably best captured the bruk spirit, making vocal-focussed and adaptable hits that were the closest that bruk came to capturing a more mainstream audience, with ‘Booty La La’ peaking at Number 44 in the UK singles charts. Describing Bugz in the CoOp documentary, Afronaut said, “We were like a football team.”

THE PEAK

The sound began to spread not only past the borders of West London but even outside of England, with Berlin’s Jazzanova joining the scene as well as the likes of Japan’s Kyoto Jazz Massive who added their own jazz fusion spin on things, and legendary house and soul vocalist Vikter Duplaix from Philadelphia. All these groups came together to form a kind of global underground community that was constantly nurturing, inspiring, and collaborating with each other, with each new addition to the bruk wave further embellishing the sound and adding their own twist.

This eclecticism was broken’s defining feature, with the genre as much of a sound as it was an attitude towards music, steeped in experimentation, culture, and breaking the rules. Although the producers weren’t necessarily trying to categorise or pigeon-hole what they were making, the sound came to be known as broken beat, or as IG preferred, ‘Bruk’. “With Mike [Slocombe], there was always an argument between me and him because I would say ‘Mike it’s called bruk’. And he’d say ‘Nah nah nah, it’s called brok, it’s spelled B, R, O, K, okay, short for broken.’ And I said ‘nah nah nah, it’s bruk. Because it's a yard thing. Because when we say things are broken, we say ‘tings bruk up’ init.’ Yeah, he didn't really understand that.”

Following the success of the early bruk productions, IG Culture teamed up with Afronaut, Dego, Demus, and Phil Asher to create CoOp in early 2000, the visionary club night that became the spiritual home of broken beat, a space for experimentation and innovation. Although the eclecticism of the genre never left, the introduction of a regular club setting further established its foundations in dance music, focusing on slightly quicker productions, closer to house and garage than hip hop. Originally at Soho’s Velvet Rooms, the night moved to the legendary Plastic People in 2003, and from here the genre really took off, with regular nights on one of the world’s best soundsystems helping to push broken beat to new audiences.

The club had a cult following, recognisable from its dimly lit room which enabled uninhibited dancing and an impeccable sound quality, regularly graced by the likes of Theo Parrish, Floating Points, François K, Alexander Nut, Four Tet and others. Recollections of the venue talk about the core of dancers that emerged, energised by the sense of unity and liberation felt there and how the darkness represented a kind of freedom. “It had a massive effect on what was happening in London,” IG tells me. “It was the past, meeting the present, creating the future. You had the freshest tunes that had literally just come out of the studio. A man could make a tune and play it out in the same night!”

Read this next: 10 venues where genres were invented

Numerous different leftfield collectives came and experimented with their new sounds, demos and dubplates, hosted by an owner (Ade Fakile) who was willing to experiment, and who cared about the music and the vibe far more than alcohol or ticket sales. “We were capturing two audiences - we were capturing an older audience who were struggling to find somewhere to rave - and then some people were just walking into the club and falling in love with it by chance … One guy, who ended up being a part of the movement, he just walked in and couldn’t believe what he was seeing and hearing. I hate the term ahead of its time, but it was!” says IG.

“We would play Sun Ra, or Madlib, or Dilla or something like that. One time I played a track by Quasimoto, and after I played it, people just started to clap,” he continues. “These are the same people that came to the club to hear that formula bruk stuff - they came for that, but they came as well to hear everything else. It was good days.”

The venue became a melting pot for the freshest sounds in London’s dance scenes, with collaboration and inspiration a key aspect of the club’s legacy. IG tells me about how Apple, the producer who claims to have made the first ever UK funky tune, was inspired by the sounds he heard at a CoOp night: “We had people like Apple coming into the club, hearing what we do, and going away and creating new sounds … after hearing what we were doing at CoOp, he says he went straight home and did that tune [‘Dutty Dance’, 2005], which became like, the first funky tune.”

THE DECLINE

However, all of a sudden, things began to change. Despite this widespread influence and respect, by 2007, just 10 years after the genre’s inception, CoOp had begun to fizzle out, leaving behind a throng of half-developed storylines and unfinished ideas. At this point dubstep and the newly emerging UK funky were hot in the clubs, grime was just beginning to take hold, and broken beat shrunk back to the shadows.

One of the key reasons for this was the changes in technology that occurred throughout the 2000s. The rise of the internet and the CDJ meant that record sales began to give way to MP3s, with other genres perhaps better suited to the shift than bruk. Forged on community and collusion, the scene suffered along with its key distributors Goya Music, which were caught cold by the change in trends. IG says, “Crash and burn, we was just going non-stop, rinsing out tunes, pushing the sound. We got to a plateau where things changed, the internet came in, it caught Goya off guard, they were like ‘You guys ain’t playing the records no more, you’re just playing MP3s’.”

He also cites the influence of (or lack thereof) major labels, which seemed to largely overlook the broken beat scene, reflecting that himself and others could have done more with the rare opportunities they were given, saying, “By the time majors [labels] came in, we probably didn’t understand that on a major you should use that platform to boost what you do to the best of your ability, rather than expect them to boost you. How do I rinse it, you know what I’m saying? Maybe I wasn’t trying to do a big enough commercial tune. I was like ‘Okay I’m just going to use the budget and do something that I can be proud of’, rather than just do something that the label can get away [sell quickly].’”

Wistfully, he tells me “Nowadays there isn’t underground - you can do an underground sounding tune and blow. Back then it was underground, we were just doing our thing, it was a subculture.” A subculture in the truest sense of the word, bruk never benefited from the rise of the internet and didn’t gain the perks of social media that other subcultures enjoyed, faring worse than some of the newer, sexier genres of the time which found internet fame and viral success. The scene perhaps found itself timed out in a sense, as the excitement and togetherness of the early years was gradually lost. Talking on that time period, IG notes, “there was maybe beef between the people involved, as you get in London scenes …”. He concludes, “It was a time of change.”

Read this next: The History of the UK House Dance Scene

Although the genre never died necessarily, it also never blew up, lacking a release that really captured the essence of broken beat and took it to a mass audience. Perhaps this is due to the expansive sound of bruk, which is difficult to encapsulate in a single track - or maybe due to the nature of its purveyors, who didn’t necessarily wish for fame, or the dilution and commodification of the sound that would come with it.

There were a handful of DJs who remained committed to the scene, continuing to push the sound as part of their explorations into UK jazz dance, soulful house and beyond, with names like Gilles Peterson, Benji B, Shy One, Marcia Carr (Girlz B Like), and Alexander Nut maintaining the faith where others didn’t, as well as high-energy, community-focused collectives such as Cyndi Handson’s Handson Family, and the only all-female bruk crew Ladybugz which was formed in 2008.

However, for better or worse, the following years mostly saw broken beat confined ever further to the underground; a genre spoken about by the heads, by the record collectors and jazz dancers, far away from the promoters.

THE REVIVAL

In recent years however, the sound has had something of a renaissance, with labels like Eglo Records, Dance Regular, CoOp Presents, Brighter Days Family, Kultura Collective, Roska Kicks and Snares, Shall I Bruk It, CoOpr8, First Word Records, Rhythm Section International, Touching Bass, Utopia Presents and Future Bounce all contributing to a revival of the genre’s catalogue.

Things started to pick up again back in 2015, and following a chat with a friend, IG decided to hit up Boiler Room and organise a reunion show. “I said to Boiler Room - let’s work together and do something, I don’t want to do it how they run some of the other shows, with people standing behind the DJ and looking cool. I just wanted to run it how we’d run it in the club, with the dancers, the crew.” He tells me that in his opinion “that would’ve been when bruk started to rear its head again.”

The years of inactivity had created room for some new heads on the scene, with producer EVM128 spearheading a revival of the sound, taking it to places it had never been. His genre-crossing hit ‘Gamma Riddim’ was released on the CoOp Presents label in 2017 and took the scene by storm, reviving the dancer culture associated with the original bruk movement, with IG telling me, “‘Gamma Riddim’ became a massive tune on the worldwide dance movement - you would hear it at the dance battles they would do around the world. The bruk thing is definitely something that the youts are relating to from that scene.”

Aside from EVM128, IG names some more new producers who are inspiring him. “You’ve got Oliver Night, Bakey, Donsurf is definitely a new bruk soldier - EVM introduced me to him last year and since then he’s just gone from strength to strength as a producer. Risa T is an amazing producer, she was a student of Alex Phountzi (CoOp Presents co-founder) - she brought a whole new technical angle to it. There’s also a lot of the Australian bruk artists. Allysha Joy is a phenomenal talent and producer. There are a lot of people who are inspired by bruk but weren’t old enough to go to the clubs who are now coming through. Then you’ve got older school people who are just coming into the sound like Dubchild, and Noodles who’s been calling it ‘brokenstep’.” Many of these producers have been guests on IG and Alex Phountzi’s CoOp Presents’ 'hour of power', which showcases these new bruk sounds every Tuesday evening on Rinse FM.

Although the CoOp Boiler Room was definitely a catalyst, the subsequent explosion of the sound was by no means a foregone conclusion. In many ways it feels like a counterpoint to theUK garage revival, which has had a particular focus on speed garage and bassline sounds which seem darker and heavier than their ‘90s inspirations, reflecting another example of the ever-increasing appetite for dark, fast and hard dance music. In direct contrast to this, the revival of broken beat has come hand in hand with a lot of DJs playing soulful house, as well as experimenting with new versions of UK funky and the jazzier iterations of UK garage being pushed by the likes of Brighter Days Family, and even by bands such as Porij and Ezra Collective. This return to jazzier, global-influenced and soulful club sounds feels like a welcome push back from those that like dance music, but don’t find the same joy within the darkness; from those who wish that dance music was, well, more musical. It seems to reflect a growing desire from a younger generation to hear soul and live instrumentation return to club-focussed music.

Donsurf comments on this, telling me, “I feel like there’s definitely a space emerging for not just broken beat, but soulful house as well. I feel like we had our resurgence of darker club music with [speed] garage coming back, maybe people are easing back - we need brighter music right now, we need those spaces where we can escape - I don’t wanna hear dark music any more.” We laugh, and he continues, “Even looking at Rinse FM now, there’s a lot more people on the roster right now playing soulful music compared to a few years ago.”

Read this next: The Mix 006: Errol

Despite this, within the sound of bruk, certain sonics do seem to have changed, with some of the early eclecticism of the genre being replaced by heavier productions, albeit in a seemingly natural progression given the passing of time, and things like new club soundsystems and a more bass-thirsty generation. Some of Donsurf’s own productions reflect this heaviness, and he considers how the sound might have developed. “At that time [the ‘90s] I reckon [bruk] felt more like a concept - with the new sounds coming through, for me there’s a distinction between ‘bruk’ and broken beat, where bruk is more high energy, heavy ragga influence, big basslines and that kind of stuff, whereas broken is more loungey, very jazzy.”

When I ask IG about this, he hesitantly agrees, saying, “I guess it's the same as jungle moving into drum ’n' bass. Very similar, but different. And then drum ‘n’ bass moving into liquid drum ’n’ bass. Or if you go even further back, disco, turning into boogie. So I will say that the elements of bruk can definitely be more hard-hitting and in your face. Maybe some of the old audience will listen to bruk and think it bears no resemblance to what they used to listen to.”

THE FUTURE

As with all changes in sound, the evolution has come with positives and negatives. While the focus on heavier productions has definitely taken the sound to new corners of the world and pushed it back into the public eye, it feels like perhaps some of the early jazz elements and genre-fluidity were somewhat lost as the sound re-emerged. As the focus shifts yet again to returning to these older values, Donsurf says, “One thing I’d like to see is more collaborations with vocalists and musicians, going down the route of making palatable songs for people to enjoy, rather than always making these heavier dance tunes - I’d like to make more accessible music, with more collaborations.”

IG also talks about how the sound is changing, saying, “I think as long as the root of the sound is there, then it can go into all different areas - like with house music it goes from jacking house, to future house, to tech-house, there’s so many different versions - jazzy house, minimal - the root of it is house, but there’s so many areas it reaches that bear no resemblance to the root of it. People are allowed to put their own twist on bruk and express themselves in the way they hear bruk.”

He compares what is happening now with bruk to what previously happened with jungle and garage, saying, “I mean, if you go back to jungle, there were a lot of breaks used, but the main one that broke through was the Amen break. I reckon that one of those youts will catch hold of a specific sound from broken beat and that sound will become what everyone relates to as bruk. That happened in garage, you know?. But with all these things, there was an original sound, which was you know, the underground, with the Black people. And then it blew up.”

Broken is still yet to blow up. However the first tendrils are there; rather than being played out in a sweaty dark basement on Sunday nights, it now finds itself on BBC Radio 1xtra, at huge festival headliners, on Mixmag’s ‘The Mix’, in new, trendy, hi-fi bars in Peckham, at student nights in Manchester, Leeds and Bristol…. the list goes on. It seems to be following in the footsteps laid by its older musical brothers of garage and jungle, where the elusive mystique of its low-key predecessors is being replaced by a burgeoning momentum, which brings with it positives such as increased exposure and a growing catalogue of experimentation and subgenres, driven by easy access to production tools and the internet. However this also can lead to a host of negatives, with IG mentioning a potential whitening of the sound as it strays further from the originators of the genre and into the mainstream, a comment that hints at the possibility of the cultural destruction that came about with the commercial growth of sounds like dubstep.

Read this next: The gentrification of jungle

However with broken it feels different. It’s still forged on a strong sense of community, with many of the older heads supporting and nurturing the newest wave of the sound. It’s still deeply rooted in the jazz scene, with Gilles Peterson providing a platform for bruk artists at his We Out Here festival, as well as championing releases like IG’s recent jazz-based project ‘The Remedy’ under his LCSM alias. This release particularly is an example of how the focus is slowly shifting back to experimentation and eclecticism, marking a full circle moment for the sound after its years away from the limelight.

Despite halting the progress of the sound, the post-2007 period of dormancy for broken beat provided a degree of protection against the dilution and commercialisation which was faced by other underground dance music genres of the era. As IG tells me, “Maybe at the time it was a change for the worse, but it definitely kept the sound in incubation, where I suppose that era remains classic, and the new generation draws from that classic sound.” In this sense broken beat has retained its authenticity, with the new producers still heavily influenced by those late ‘90s and early 2000s sounds. After a tentative re-emergence, the genre is now better placed than ever before to capture the hearts and minds of a new generation, as dance music begins to rediscover its soul.

Jamaal Johnson is a freelance writer, follow him on Instagram

Update 26/09: This feature was updated to reflect additional information on important DJs, vocalists and collectives associated with the broken beat scene