Features

Features

J Dilla’s music will always sound like the future

On what would have been the late Detroit beatmaker’s 50th birthday, Thomas Hobbs writes about J Dilla’s unparalleled genius and how he inspired generation-after-generation of producers to move at their own pace

“If you hear a voice within you say you cannot paint,” wrote Vincent van Gogh, “then by all means paint and that voice will be silenced.”

Whether it was concerned doctors, heartbroken family members and friends, or simply his own exhausted inner conscience, the late producer J Dilla (who should have turned 50 today) heard plenty of dissenting voices warning him to put down his sampling machine and take a well-earned break, especially during the final few months of his life.

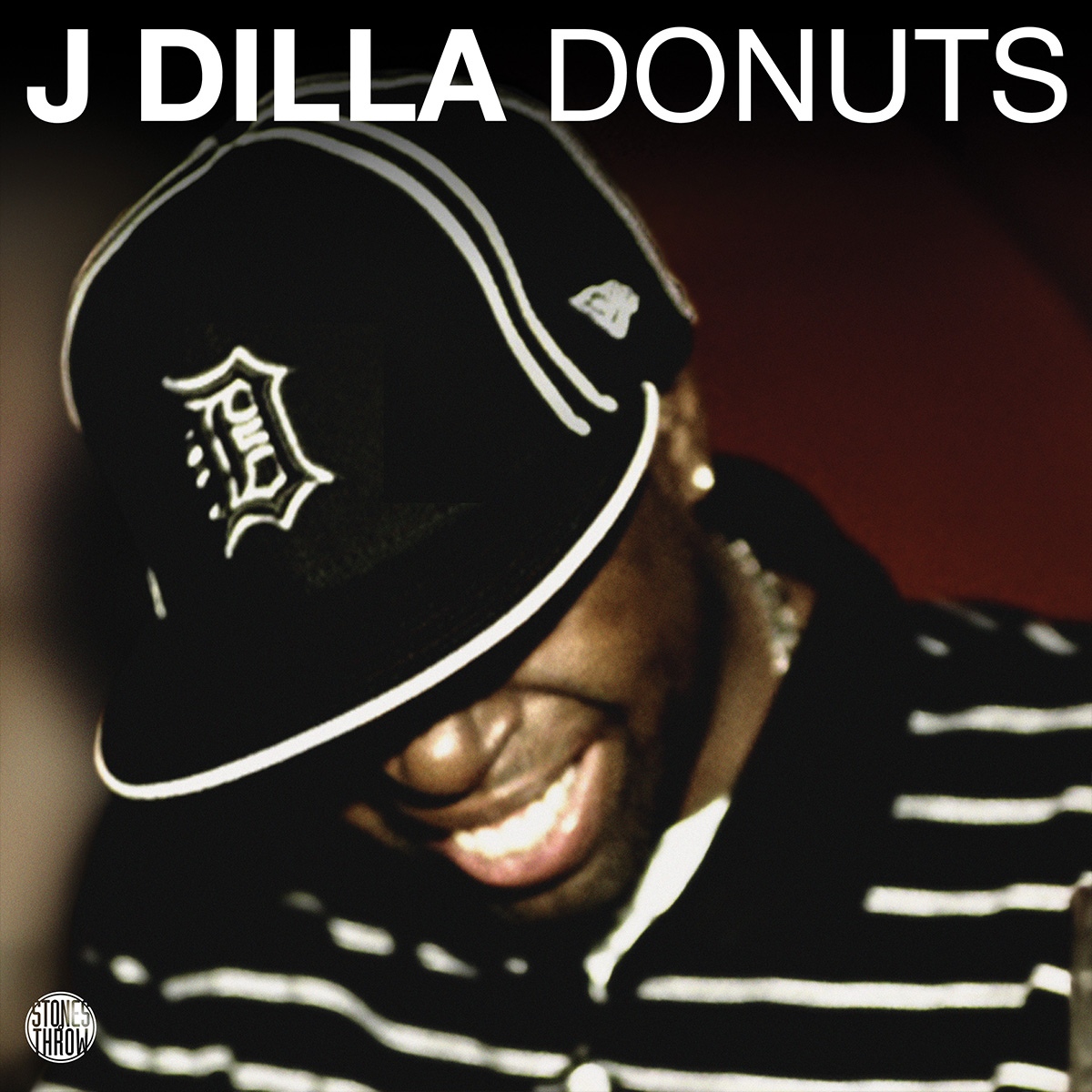

Suffering from thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) - a rare and incurable blood disease that causes clots to form throughout vessels in the body and subsequently results in organ failure – Dilla (real name James Dewitt Yancey) could barely move, let alone talk. Yet this didn’t stop him turning a “sterile white” hospital room at LA’s Cedars-Sinai (the same medical center where Biggie died) into a mini studio—complete with an SP-303, a turntable, well-worn headphones, and crates of records to sample. Any messages he was too “broken and blue” to share with his own voice, Dilla simply channeled into the music; most of it forming one final masterpiece, ‘Donuts’ (released on his birthday 18 years ago and only three days before he tragically passed away at the age of 32).

A perfectionist who’d experiment until samples had reached odd, new-fangled shapes and frequencies, this intense creative process meant a sick Dilla’s hands regularly swelled up like a hornet had just stung them. He would work through this pain until it finally became unbearable and - only then - he’d take a break on the pillow while his mother, Maureen, massaged his fingertips so that the bones stopped aching. Temporarily healed, Dilla got right back to work, warping synths and eagerly handing passing doctors his cans so they could preview some of the thunderous, wavy concoctions he was constructing.

Particularly with ‘Last Donut of the Night’ and ‘Time: Donut of the Heart’ (with its chopped up “there comes a time” vocal sample), these quick-fire nostalgic beats gave the impression their creator saw death more like a motherly caress than a cruel, blunt ending. ‘Donuts’ (artwork and all) is the sound of a man on a mission, looking into the abyss with a warm smile on his face.

To the J Dilla super fans, it can be frustrating to see the producer reduced to campfire tale anecdotes and urban legends (including the false story of the title of ‘Donuts’ being inspired by Dilla seeing a Randy’s Donuts shop sign from his hospital window). But whether you believe all the posthumous mythology around him has become too mawkish or not, the way J Dilla embraced new sounds, even when staring right down the barrel of death, remains a crucial way of understanding his artistry.

From Detroit’s finest underground rap producer, inspired by the likes of Pete Rock and Diamond D, to perforating the mainstream with his mind-blowing production for artists including Busta Rhymes, Janet Jackson, Erykah Badu, A Tribe Called Quest, Common, and D’Angelo, J Dilla’s music remains futuristic despite nearly 20 years since his passing. And, this is largely down to its structure.

Read this next: 20 of the best Detroit rap tracks

Most of the drums from his rap production contemporaries were quantized and adhered to the steady 4/4 time signature, but conversely, Dilla trawled out kick drums and dragged hi-hats so each arrived when you were least expecting them. He told bassists to play their notes slightly behind the music to build tension, this “back phrasing” technique (also used by Miles Davis) resulting in rap beats that staggered forward like a drunk walking through a swamp in logger boots. Just like an insolent school pupil, keeping time was a foreign concept to J Dilla.

All these sonic delays, paired with the abruptness of snares that always arrived a second or so too early, meant J Dilla’s hissing, lo-fi beats replicated the feeling of listening to music at the height of an acid trip: a confusing yet transcendent experience, where you temporarily become convinced that music is somehow capable of both slowing down and speeding up simultaneously. Without the need for an illicit substance, J Dilla let us hear rap production from a brand new, psychedelic vantage point — confounding our expectations like it was his life’s purpose. The fact he was also such a colloquial emcee, who could make rapping over such complex beats seem so effortless, is testament to his artistic versatility.

Beyond all this technical innovation, it’s the teaching that means J Dilla’s legacy remains so timeless. On Slum Village’s ‘Raise It Up’, he samples the topsy-turvy, malfunctioning Gameboy Color synths of Daft Punk member Thomas Bangalter’s ‘Extra Dry’, making them sound less high pitched and more like a husky Doug E. Fresh beatboxing. On Busta Rhymes’ ‘Show Me What You Got’ he takes an eerie, grumbling bassline and soul-stirring guitar chime from a Stereolab song, flipping these layers so they’re the central tenet of an “immaculate raw” boom bap beat. And, on Pharcyde’s ‘Runnin’, Dilla’s reference to Stan Getz and Luiz Bonfá's ‘Saudade Vem Correndo’ is pure bliss, using the original’s popping drums and cascading samba guitar notes to replicate elegantly flailing bellies caught up in the middle of a euphoric umbigada dance. It was one of the first prominent Brazillian bossa nova samples on a mainstream American rap record, and concrete proof of Dilla’s infinite harmonic range.

These three examples show how J Dilla’s crate digging borrowed from all kinds of genres (electronic, jazz, alternative), which meant listening to his beats always ensured your horizons were going to be widened. After playing Dilla’s beats, looking up the samples is such a big part of the ritual, and I’m sure the producer got a big kick out of all the journeys he inspired fans (including Aphex Twin) to go on. Speaking from a personal perspective, I’d know next to nothing about classical music if it wasn’t for Dilla putting teenage me onto Passereau, Mussorgsky, Debussy, Mozart, and Bach through his samples. Jay Dee forced me to explore classical music, which I had previously ignorantly associated with my old-fashioned grandparents, and made it suddenly seem like the coolest thing in the world. He was a conduit for musical discovery.

Such an obsessive nature meant Dilla often found textures burrowed into music that other producers overlooked or simply didn’t spot, with his sample of ‘Rhapsody of Blue’ by Gershon Kinglsey and Leonid Hambro the perfect example of this. He samples a crawling and sporadic piano melody that doesn’t appear until the 11.04 minute mark of the original song, making this off-kilter sample the essence of his criminally underrated and dusty ‘Hambro’ beat. In Dan Charnas’ brilliant Dilla Time book, he writes of how J Dilla didn’t just “skip through the records, needle dropping for interesting parts” to sample, but rather “listened and listened to entire songs.” Patiently unearthing diamonds in the rough was so crucial to his approach.

Collaborators also talk about how J Dilla wasn’t the most talkative in the studio, laser focused on creating magic and sometimes operating not far off a non-verbal level. He really came to life when the music stopped and there was a chance to take artists to the club to celebrate and pop bottles. This lack of dialogue only adds to his mystique, but if you want to get a real sense of the life experiences that made him who he was, it’s all there in the Madlib collaboration ‘Survival Test’.

"There's a whole lotta filth out there / Y'all can't be for real out there / Fake gangstas better chill out there / Y'all know the deal out here / It's real out here, meals out there / And n----s got bills out here / Everybody tryin' to live out here / Everybody hustlin' out here / And you don't want your biz out there / Hoes be on some bullshit out here / You don't wanna be without here / N----s ain't giving a fuck, they will pull it out here.” Here, on this Jaylib heater, Dilla raps about the Motor City like it’s the desolate set of a bloodthirsty Western movie, and he gives us a powerful sense of the violent lifestyle he had to overcome to shine so brightly in the music business.

Read this next: Uncovering Moodymann's Detroit hip hop origins

My personal favourite J Dilla beat is one of the most obscure. Dilla’s remix of Cincinnati rap group Mood’s ‘Secrets of the Sand’ has a way of playing my heartstrings like they’re his own personal fiddle, with the producer taking a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it guitar cry from a live rendition of Lenny Breau’s ‘That’s All’ (it appears at the 4.24 mark) and muddying its sound so it’s as if it is emanating from the bottom of the Atlantic ocean. This is a strangely emotional experience, the music sounding like beauty emerging from the hidden depths of solitude. Like all the best J Dilla beats, it inspires career-best philosophy from the rappers it features, with Mood’s Donte pledging to “Open the doors to death with the keys to life”—a mantra that Dilla also seemed to live out through his art.

Much like the previously quoted post-impressionist painter, J Dilla had a compulsion to create vibrant art that superseded any kind of inner storm; the “process” resulting in a salvation and glory that made all the pain and strife feel worth it, somehow. To Van Gogh and J Dilla the only voices worth listening to were the ones that said: “Go paint!”. And however much longer humanity lasts in the face of existential struggles, they’ll still be saying that J Dilla’s beats sound like the future.

Thomas Hobbs is a freelance writer, follow him on Twitter