Features

Features

What is Coachella?

Now the dust has settled... David McGraw reflects on weekend 1 of Coachella Valley Music & Arts Festival 2023: a commercial colossus that's become a pre-eminent institution of the music industry

On Sunday night of Coachella weekend 1, just like every other night that weekend, south-easterly winds swept from the Pacific ocean over the land. Colossal columns of wind pulled dust out of the ground and into the air, over crushed reusable aluminum water bottles, and the dismantled material remains of 2023’s festival––it is as if the Mojave perpetually tries to pull this land back into dust and sand, until it consumes the finely-tuned and well-irrigated oasis of Indio, California, one day becoming desert anew. Frank Ocean’s maligned Sunday night performance of Weekend 1 will live on on YouTube for a while though, until all the cellphone videos eventually get taken down, or maybe until the data centres that house them are swallowed up by the sun.

Coachella Valley Music & Arts Festival has been around for almost 25 years now, but has undergone substantial conceptual changes since its inception, marked by several pivotal performances: first, in 2006, with Daft Punk’s pyramid bringing about a shift towards spectacle in dance music, and again in the early 2010s, around the time of the infamous Tupac Shakur hologram performance, it became the face of a new, high production-value strain of festival culture that marked the rest of the decade. Beyoncé’s now-legendary, maximum-octane, intricately choreographed and pyrotechnic 2018 performance set a new standard for headlining acts, which, to some extent, recent Top 40 headliners have attempted to emulate in energy and extravagance. On nights 1 and 2, Bad Bunny and BLACKPINK this year delivered maximalist offerings on the mainstage, while Metro Boomin brought a similarly-maximalist cache of hip hop stars to the Sahara tent, accompanied by a legion of brass-instrumentalists and dancers, as well as, of course, a show of pyrotechnics and enormous LED visuals.

Through these moments of intense spectacle, Coachella has by now become an invincible institution of American and global music and fashion media, existing physically in the Coachella Valley in its annual two-weekend run, but more broadly as the archetype of American festival culture, and especially its total-commercialization and symbiosis with various corporations like Adidas and Heineken.

Read this next: How Instagram is changing the design of clubs and festivals

There is a Coachella audience in the Southern California desert during the actual festival, yes, but everyone witnessing smartphone video clips, YouTube streams, and reading think pieces, during the weekend and in the days after are as much of an audience for this festival as the punters who pay exorbitant amounts of money to split an Airbnb with their friends, or camp on-site. As are the myriad influencers and music industry faces that also haunt the grounds. With last decade’s social media arms race and the ubiquitous proliferation of cellphone cameras that feed directly into these networks, every inch of Coachella is a stage (even if it looks more like the ritziest American state fair in existence, with large interactive art pieces including an Instagram-famous rainbow-colored tower, encircled by music tents and a giant Ferris wheel), and arguably all of those attending, regardless of having a performance slot on the line-up or not, dress to perform for social media — it’s as if every moment spent on the grounds is live-streamed to social networks, everyone attending plays the role of an extra in someone else’s Coachella story.

The festival’s unlikely growth, from a marriage of punk and rave promotion on the grounds of Empire Polo Club in the late ‘90s, into the gargantuan media institution that it is today, has seen the festival move further and further away from the 20th century conception of what constitutes a music festival, instead becoming the predominant exemplar in the music industry of commercialization in the festival space, particularly evident in how deeply the festival has courted (and is now intrinsically associated with) the burgeoning influencer-marketing industry. That being said, after a full weekend within the all-encompassing endorphin funnel of Coachella, all synapses frayed and money spent, it’s remarkably clear that, underneath it all, the whole operation would collapse without Goldenvoice’s consistent, shrewd booking of dozens of artists at the peaks of their creative abilities and careers as performers, and the festival offering these artists a variety of unique stages with different personalities, where they’ve consistently delivered once-in-a-lifetime performances to whomever happens to witness them. Audiences, having spent extraordinary amounts of cash to come out to the festival, expect nothing less than perfection.

The desert winds peaked on Thursday evening before the festival commenced, funneling through the campsites and the festival grounds, tearing away anything loose, including the tents being hastily constructed by festival-goers setting up camp for the weekend ahead. In the distance, the upper section of the legendary Sahara tent, which might be mistaken for the Chernobyl containment dome, could be seen rising above the palm trees, with purple light reaching up to the clouds as production crews throughout the fest worked through the night to prepare.

With crowds filtering into the grounds the following morning, the massive fields of green grass seemed like an oasis within the complex of the festival itself. Because of the necessarily Byzantine security operation surrounding the actual venue—golf carts and uniforms and two-way radios are a commanding presence all over the festival––you could also be forgiven for mistaking Coachella, visually, for a massive military camp that happens to have Coachella in the middle. This degree of security creates headaches for all involved, but given the not-unfounded anxieties of gun violence in America and overcrowding at large music venues, after incidents like the still-recent atrocity at a Las Vegas festival in 2017, attack on Orlando’s Pulse nightclub the year prior, and crowd control issues leading to the Astroworld stampede in 2021, the heightened security very much feels necessary, adding to the reticence some still feel about attending festivals post-COVID. Several audience members agreed the extensive security presence allowed them to feel completely safe throughout the weekend; it gave them space to focus more on the music and experience of the festival, without fearing for their safety. As a side effect though, those who were able to finagle off-site housing for the weekend dealt with hours-long waits getting back onto the grounds, in addition to the extreme traffic congestion that this event brings to the surrounding area.

The Sonora tent, an intimate, air-conditioned space that’s a recent addition to the festival and located closest to the two main stages, hosted a scattered assemblage of younger acts earlier in their careers, including a few rising artists from the UK such as Lava La Rue, Bakar and Nia Archives.

Lava La Rue played their first ever American festival performance in the Sonora at 2:PM on Day 1. High stakes, but “it's really cool to be able to be booked for a festival like this, considering I don't feel like I've actually put out a proper body of music before,” they say, shortly after their performance, at a fold-out table next to some crowded artist trailers.

“All these bookings have been based off of two EPs, one that I wrote when I was 17, and I put out on mixtape and some SoundCloud stuff, but I've never put anything that for me feels hot.” Despite their modesty about their oeuvre, they have had a well-established musical and visual identity as an artist for a while now, as well as a powerful stage presence, and through streaming apps and social media, Lava has a fanbase that extends far outside their native West London.

“I think lyrically my songs are very London and queer, and my experience as a second generation Caribbean migrant living in Britain, my music touches on all those things, and society. However, the production has got a West Coast flare to it, and it's very inspired by a lot of West Coast psychedelia, I suppose. Half of my producers that I work with are based in LA, and so you do kind of get that flavour, but I'm from West London and I always say my music genre is West London meets West Coast.”

Rising star Nia Archives closed out the Sonora tent on Saturday. “It was super cool to be a UK underground artist to be playing one of the biggest festivals in America, bringing the UK sounds to an American audience. I get anxiety before every show and playing something with so much hype and pressure around it made it no different! Sonora was a vibe, I think it was the only AC’d tent on site… I was nervous as my set was at 10:PM clashing against some huge artists,” she says, referring to Eric Prydz’s HOLO just a stone’s throw away at the Outdoor stage, “but I was gassed to see a big crowd turn up for most of my set and people were skanking!”

The pressure of having a Coachella slot, let alone one that is earlier in the day, impacts those performing, but within each tent people do turn out. According to New York-based DJ Francis Mercier, who played the Yuma (Coachella’s hub for house and techno specifically, fashioned like an LA warehouse party at midnight, offering both a respite from the heat and an incredible selection of dance music regardless of the time of day) at 1:PM on Saturday, said that “at first, I was a little bit hesitant, the first 10 minutes were a little bit light. By 1:45, there were a good 400, 500 people. It was a great turnout. It picked up really fast, and we had a great crowd response.”

Mercier had to work harder to catch the vibe of the crowd, what they wanted, but then found them responsive. “I think personally the audience in California is much more challenging. The further East you go, the easier it is, for me and for most house and techno artists. Because I think in Europe people are more open-minded, they're more receptive to the Afro house, or just experimental music in general. The further east you go, the more it works. West Coast, I still feel like American tech-house is really big here. If you don't give the audience a lot of energy and you put on a show, I think they're kind of like…”

A bit lethargic?

“A bit slow, yeah.”

Still, it was early, and, by the end of his set at 2:PM, the audience was kicking.

Mercier’s slot on the Coachella bill this year holds a certain power and meaning for him: “It's really big for me because Coachella has hosted some of the biggest names in the industry, from the likes of Tiësto to Gorillaz, Frank Ocean, Blink 182, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Calvin Harris, you name it. Everybody you can think of. So to be able to be in this kind of line-up, get this visibility in the US and across the world, coming from a small country like Haiti, it really means a lot for me. I think I'm amongst one of very few artists, or probably one of the first Haitian artists to perform at Coachella.”

Read this next: "It's ecstatic": DJ Koze, Lakou Mizik & Joseph Ray on the power of Haitian Voudou Music

In the Yuma, where house- and techno-heads attending the fest would spend most of their time, the booking is alternately global and fed in from the local dance music scene in Los Angeles. About how much of an “LA” versus global dance music industry presence Coachella has, LA-based SOHMI (who played both at the Yuma and Do LaB during weekend 1), says: “I think [LA and Coachella] feed into each other a bit. For one, the main thing that makes me feel like they feed into each other is the people, the scene. There's so many familiar faces out at Coachella, who I see in the LA club scene. So it kind of feels like we're all just out here together in the desert, just in a bigger open field with less pollution.”

Tucked away in a corner of the grounds, next to a flower-covered Adidas building and thankfully located some distance from the garishly-branded Heineken House (which featured a wild line-up of its own but was also located unfortunately close to a large bank of outhouses), a smaller tent housing James Murphy and 2manydjs’ Despacio installation offered a gentler analog to the Yuma. Too dark to photograph inside, revelers all but abandoned their phone cameras and let loose to the impressive soundsystem, comprised of six speaker nodes each outfitted with McIntosh amplifiers, arranged circularly around the checkerboard dancefloor with a disco ball overhead. With experiments such as phone-neutering Yondr pouches having now fallen out of fashion, abandoning the concept of lighting altogether seems to be an effective, less invasive strategy towards the same end––in the near-total darkness, people finally loosened up enough to lose themselves to whatever weird, wonderful records James Murphy and 2manydjs had excavated for the weekend.

Coachella’s rise in American public awareness was concurrent with the country’s early 2010’s drug-panic, surrounding the use of adulterated MDMA at electronic music festivals, but there was little outward evidence of this drug’s use at Coachella weekend 1 this year. Broadly, the drug of choice was $18 mixed drinks, rather than ecstasy. You could arguably feel the absence of psychedelic drugs in the absence of interaction people had with each other, which seems also to be a function of technological conditioning and the pervasive attitude of passive consumption; walking the grounds, there were some smiles, but also a lot of exhausted and stone-faced people, overwhelmed by it all.

Read this next: After the pandemic, LA's rave underground bounces back stronger than ever

Dance music works at Coachella, but in general does not work exceptionally well here in comparison to other festivals, because Coachella is hedonistic in terms of consumption and spectacle, rather than social pleasure. At the end of the day people come here to ingest rather than connect; they ingest music, expensive food, $18 drinks, Instagram traps. And to slather the desert in thousands of pounds of sunscreen and mire themselves in streetwear partnerships. In other words, any semantic connection this festival’s name has with counterculture is vestigial at this point.

The Faustian bargain you make attending the festival is that, despite the inherent effort and cost of attending, by doing so you will miss many incredible performances, more than you could possibly see even if you ran circles around the vast grounds at full speed, and definitely more than you’d miss by just flipping through the official live-stream channels on YouTube. There are seven official stages, not even counting the Do LaB, and Despacio, and the Heineken House, all with music playing essentially throughout the entire three day weekend. Thankfully though, if you’re committed, you can flip back and forth through replays of what you missed the following morning on YouTube from your tent before the festival starts again––all of which are high enough in production value that they adequately communicate the experience of actually seeing these artists in person. But that raises another issue related to the future of the fest (and possibly live music in general in this age of infinite DJ clips and live-streamed performances): if you can see more of the festival from home on your phone, and garner a more complete experience of its music that way, then what is the point of even attending? The value of Coachella is that performers rise to the occasion, and that you’ll encounter transcendent performances unexpectedly, often in transit.

The mid-sized Gobi stage, positioned on the opposite side of the grounds from the Yuma, is maybe the perfect tent for these kinds of unexpected experiences. Overmono played an early, sparsely attended (but energetic) set on Friday, but those arriving early to see SG Lewis at the Outdoor Stage, or Kaytranada’s hit-laced set which followed, would have caught some Overmono as well on the way––you could see passers-by’s interests being piqued, some of whom were compelled to stick around.

Read this next: Overmono are growing into a top-tier live electronic act

Friday’s line-up for the Gobi tent was a work of art in itself, with machine-drum-tinged Californian grunge absurdists The Garden following an absolutely ethereal Yves Tumor performance, which was itself preceded by a high-energy delivery from Tobe Nwigwe. But after The Garden (and their surprise guest Mac Demarco) departed the Gobi stage, a large steel cage was rolled out that would imminently house Whyte Fang (AKA Alison Wonderland).

Alison is a legendary figure at Coachella, having rocked the festival numerous times, including a monumental set in 2019 headlining the Sahara. Earlier in the day, in the artist section behind the mainstage during Pusha T’s set, she sat at a picnic table with the prodigious Erick the Architect, where she described how they met and later kept in contact during the pandemic, and what led them both here.

“I don't remember the name of [that festival], but they put me in a separate trailer away from all the artists, and it was actually quite a threatening security situation. And I was very, very, very scared and alone and freaking out. So outside I hear this amazing piano getting played, right outside this little box they'd put me in. And I didn't know Erick at the time. He was just playing piano, and I walked out and I’d been crying. I said, ‘hey, having a really hard day. Do you mind if I just sit next to you while you play piano for me?’ And he said, ‘no problem,’ and just let me sit there. Honestly, it cured me and I felt a lot better. He plays incredible, just improvising on the piano, and it was beautiful, and that's how we became friends.”

“And then throughout the pandemic we’d text here and there and then we'd send memes of the guy with the dick during COVID. You know the one,” she says.

“If you saw it, you would know which one it is,” says Erick.

“We’ll send it to you.”

The friendship eventually evolved into a musical partnership as well, for Alison’s most recent venture, the Whyte Fang album ‘GENESIS’, which leans into harsher warehouse-inspired territory and is influenced by witch house as well, littered with sharp, punchy kicks, stabs and loops––all of which has come together during a surge in creative energy over the course of her pregnancy, culminating with this Coachella performance under the Whyte Fang moniker on Friday, the day of the album’s release. And to top it all off: “Next week I'm eight months!” she says, as she leaves to prepare for the performance.

When the time comes for Whyte Fang to take the stage, the Gobi is packed to the gills. Engrossing time-coded visuals are projected onto the metal grates, the crowd thrashes, and Erick emerges to a rapturous audience halfway through, to perform their collaboration ‘SCREAM’, which merges the spacious, synthy atmosphere he championed in Flatbush Zombies in the early 2010s with Whyte Fang’s driving, festival-fuel production style.

“I wanted this to be a whole adventure visually, lighting wise, not really about me,” she says. Performing as Whyte Fang “was really weird, because I'm so encapsulated in this box. And my vision, because of all the grating, I can only see so far. To me, the whole show was more about the show than myself anyway.”

This somewhat belies the true ethos of Whyte Fang and Alison’s approach to music in general; in the short moments the audience sees her through the steel grating, it’s clear how physically taxing this performance is on her, how much she is giving to it. Despite the cage and visuals obscuring her appearance, Whyte Fang is, for Alison, another way of facilitating a more profound connection between her and her audience through spectacle.

Before the show, Erick expressed the extreme lengths to which headliners and their production crews go at Coachella, in terms of both expense and artistic exertion, in order to deliver these transcendent experiences for those who show up for them. “I love festival culture, but it starts to become about, ‘hey, I'm at the festival.’ As opposed to: these people are up here, losing money, to make you guys smile and dance and have a good time. I think people try to look at us and it's like ‘they're doing this for money’ or ‘they all must be so rich.’ And sometimes I think because of the presentation and how serious we take our craft, they might forget that. I never want people to forget that.

“I also want to say on the record that I've never met a woman that works as hard as Alison,” says Erick. “She's fucking pregnant, bro. I tell her only a woman could do that. And I really respect her for that. 10 out of 10. I've never met anybody that could do something like that. She's performing tonight, pregnant. Have you done that?”

“I’ve paid him fifty dollars to say that,” says Alison.

On Saturday night, the second night, the second largest tent at Coachella, the Mojave, failed miserably to contain a gigantic mass of people, packed together like penguins during an ice storm in the desert heat of Southern California, spilling out far beyond the physical bounds of the tent. Inside, the humidity was insane. They were all there for Jai Paul, in the flesh, for the first time ever.

Jai Paul that night not only felt the pressure of giving his first live performance ever to a crowd, of a size far beyond what most could possibly imagine receiving in their entire careers as musicians, but also the pressure of putting a public face to his music after more than 10 years of obscurity, with his humanity up against his audience’s expectations: as every single fan of his has created their own, flawed version of him in their heads. A whole generation in music has come and gone since his early releases and leaks, and his tracks have bookmarked all kinds of beautiful and painful memories for listeners dispersed across the globe, all with their own associations and interpretations of his intent, all in the absence of the man himself. In the press, he’s been compared to Prince. That set of preconditions seem to have all catalyzed in this moment of his debut performance: a true moment of transition between artist as the ultimate anonymous music industry underdog of the 2010s, and a future in the public eye.

Read this next: Review: Jai Paul's London live debut was a delirious, heart-warming homecoming

After some delays, an ensemble featuring his brother A.K. Paul and others took the stage, arranged around boulders and in front of CGI cave-diving visuals. Jai floats out onto the stage, in dark sunglasses and long hair, hands up, guarded, close to the microphone. For all his visible anxiety, his voice was perfect, running through ‘He’, and then the originally-leaked tracks ‘Crush’, ‘100,000’, and ‘Chix’. On the pre-chorus of ‘Do You Love Her Now’, Fabiana Palladino gave voice to the disembodied female vocal on the track that had been kicking around in the audience’s heads since its release in 2019. The crowd took a second to register that this was the woman behind the vocal, but then erupted in cheers as she hit the mic.

Perhaps the most unexpected delivery in his setlist was ‘All Night’, a cut that, while beautiful, hasn’t stood out quite like the others from Paul in the years since it leaked. At Coachella that night, though, you could feel thousands and thousands of hearts drop at once when those chords came in. Maybe Jai felt something then too; halfway through the song, he sat center stage and cracked a warm smile in the spotlight, seeming to let his guard down for the first time in this most strange and incomprehensible situation he found himself in. However, the emotional power of this one paled in comparison to ‘Jasmine’, where it seemed like a sea of people experienced some kind of indescribable, otherworldly catharsis. Tears were shed. ‘BTSTU’, which followed, was a victory lap, with the entire crowd singing the chorus, “I know I’ve been gone a long time/I’m back and I want what is mine,” a line which has resonated for years at this point for different reasons, but feels like a prophecy that has come true now for Jai’s own life and career. Hailing from London, it seems almost strange too that Coachella of all places would be the venue to house this debut moment for him; money talks, of course, but also, given the particular power Coachella held over the global music consciousness at the beginning of last decade especially, on some level, this performance was not only a re-enactment of what could have been had history unfolded differently, but it felt clear this was also the beginning of a long-deserved second act for Jai.

It’s likely that anyone reading this has a fully-formed opinion already on what happened the following night. There have been countless first-person accounts on TikTok and Instagram, podcast interviews with fired ice skaters, takedowns by prominent media outlets and other artists.

Frank is said to have had an ankle injury the week before the performance, according to his team. To what extent this injury was involved in the eventual decision to take down the original ice rink stage (which would have been the central feature of the performance) and modify the act for Sunday of weekend 1 is unclear, though it was the reason given by Frank’s team for his dropping out of the festival for weekend 2.

According to skaters hired for the performance, Frank seems to have been in talks with the festival with regard to some form of hesitation, disappointment, or disapproval he had with the festival and/or festival production ahead of Sunday.

On Sunday, the decision was made (or was carried out) to disassemble the ice rink stage that had been constructed that day. The extra time it took to disassemble (or possibly even melt) this ice rink and then reconstruct the mainstage caused delays to the show, between 45 minutes and an hour after the 10:PM start time. Earlier, in the afternoon, skaters who were to play a role in the show were alerted of their firing, or were requested to walk the show in their custom Prada uniforms in lieu of the skating performance they’d been training for. All of these changes happened unbeknownst to audience members, many of whom had been standing in the densely packed front-of-stage for over 10 hours to see Frank.

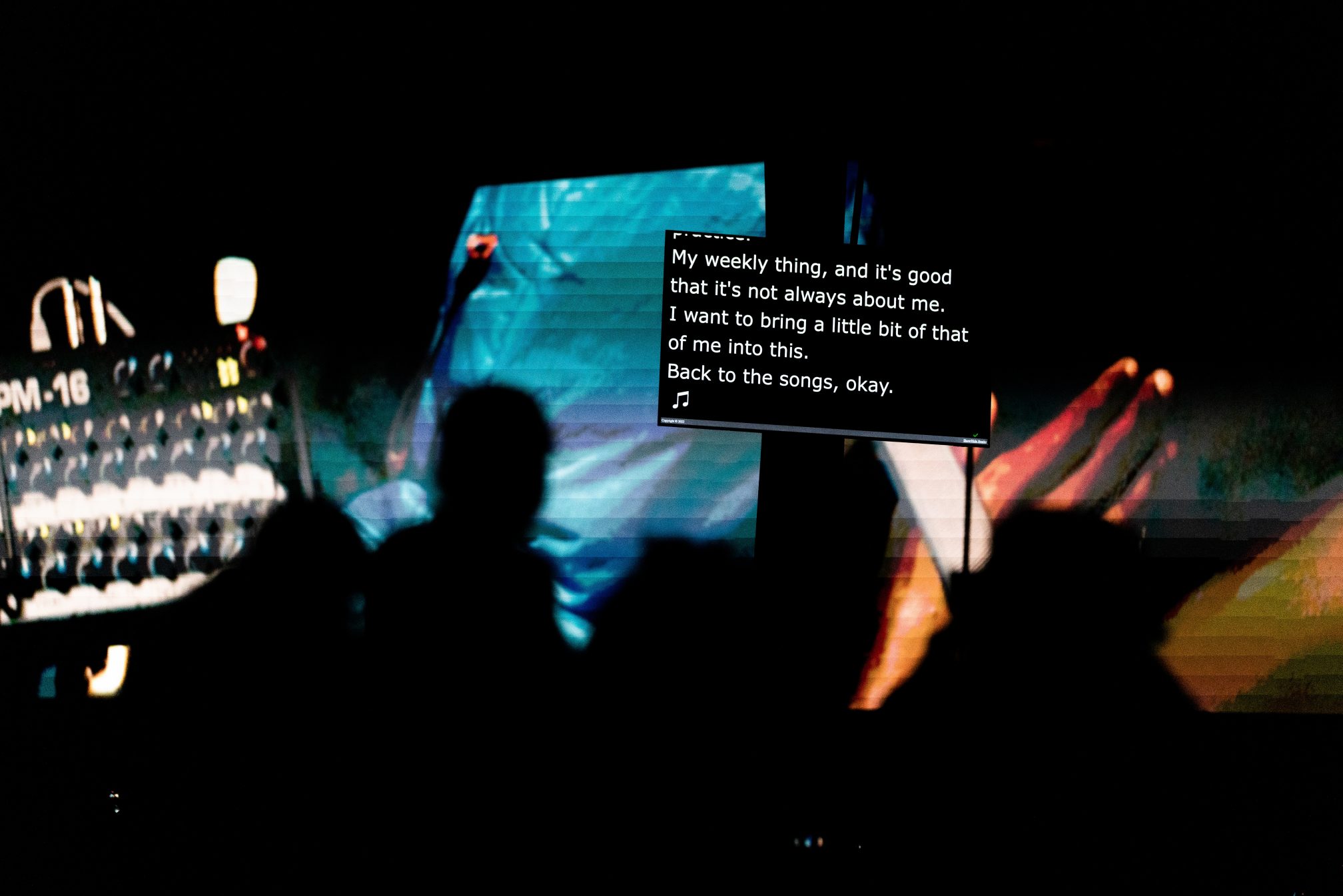

The show then began, and for a while, all that was visible was a massive video feed of the skaters walking in concentric circles in opposite directions, situated on the section of the stage closest to the crowd. Eventually, the cameras start to catch an extensive studio production setup in the background behind the skaters, containing drums, keys, an array of analog synths, mics, and studio equipment, and then brief glimpses of Frank himself, in a blue Mammut puffer jacket.

He opens with ‘Novacane’, arguably his breakout hit, off debut mixtape ‘nostalgia, ULTRA’. A now-removed video of the entire performance showed a mass of people in the front, bouncing, and calling out the lyrics, and the same is true for Frank’s delivery of ‘Crack Rock’. Both tracks pointed to the show’s intent: the lyric “met her at Coachella” generated a powerful response on ‘Novacane’ for obvious reasons, but, much more importantly, on ‘Crack Rock’, for the verse “fuckin' pig get shot/Three-hundred men will search for me/My brother get popped/And don't no one hear the sound,” Frank purposefully omitted the third line, allowing the crowd to sing for him.

Music was bookmarked by long stretches of silence, as those on stage prepared for what came next, forcing those in the crowd to be present in the moment, whether that meant listening to your thoughts––“what track is next” or “those dudes next to me won’t stop fucking talking.” In those long stretches of silence, people had no choice but to hear the chatter of those around them, their knees buckling after 12 hours trudging around the fest. Silence might have, in theory, also forced people to be receptive to what experimentation was being offered up to them but clearly that didn’t happen for most: out at the edges of the sea of audience-members, the atmosphere was verging on hostile.

Frank performed a heavily-reworked iteration of ‘Blonde’’s ‘White Ferrari’, singing beautifully over rezzy synth arpeggios, far removed from the studio version. At one point, he left the mics, danced and mouthed the lyrics to a Hi-Fi mix of ‘Chanel’, which then devolved into an unreleased Sango remix of the track, mixed by DJ Crystallmess. He also addressed the crowd directly, commenting on his presence being an attempt to honor the memory of his brother who recently passed away in a car accident, offering an anecdote of a happy memory they shared at Coachella seeing Rae Sremmurd years ago.

With regard to why this set garnered so much ire, it’s clear that the issue doesn’t lie within the formal elements that are the most frequent target of complaints — i.e. Frank dancing and not singing to ‘Chanel’, his Jersey club interlude with Crystallmess on the decks and New Orleans Bounce artist Ha Sizzle as a twerking security guard — as other artists at Coachella incorporated these types of elements into their performances. It’s common practice for rappers to perform over the original vocal of their tracks, and other minimalist stage setups at this year’s iteration were well-received. For example, starting about an hour before Jai Paul in the Mojave on Saturday, Yaeji had a large crowd in the palm of her hand at the Gobi. Her live set eschewed any kind of DJ equipment or instruments, with the artist herself singing over her tracks, accompanied by dancers: a big rave with no decks (and another classic case of unfortunate simultaneous Coachella booking, against Jai Paul).

Rather, it’s the interpretation of apathy from Frank around these disorganized elements of his performance that is the root of this controversy. Whatever elements crystallized into the performance Sunday, they caused it to resemble more of a conceptual art installation than what we expect a typical Coachella headline show to be, which, these days, would be something on-par in spectacle to a Superbowl half-time performance. Any degree of apathy towards an audience, whether or not there was indeed apathy on Frank’s part, is almost worse than open disdain for a crowd, because it leaves no room for them. The role of an artist at this festival is to use performance to mediate connection, or even just hold attention, between themselves and the audience. The stage-change additionally seems to have been particularly brutal on the production crews and frustrating for corollary performers who weren’t able to deliver the performance they’d been training for. Still, there was a compelling, if unfinished or incomplete, performance there, and one which did offer moments of transcendence, for those who were able to see beyond their expectations.

Read this next: Frank Ocean hints at new album and debuts reworked at Coachella

“I think conceptually, I really enjoyed the show,” said Caché, a fan from Chicago who attended Coachella to see Frank perform. “I also enjoyed it, period. And I could see his process and that is a very crucial part for me. I love seeing an artist in their process, and that's what I feel like I got to see on Sunday. I feel like I got to see Frank Ocean doing his process. And these little interludes and things, these were moments that, in his mind, this is how... If he were to do a performance, just because he was doing it and not because of a contract or something, I'm sure it would look something like this. Just him in a space, singing and playing beats and doing cool shit like that. So I really enjoyed that performance. I loved the ‘White Ferrari’ remix. And I was like, period. That's what you're supposed to do. I love when an artist remixes their old songs for a performance. I think when people come to festival performances especially, and they're expecting a carbon copy of the album, you're going to be disappointed. The album and a live performance are two different things, and then a concert and a festival performance are two different things. That's just not the reality. So if people came to this performance thinking they were going to get Frank Ocean from six years ago and his album, that's just not what it is. He's grown as a person and things have changed.”

With both Coachella and Frank’s team having no choice but to attempt to save face following the media backlash, it’s easy to assume some level of greed or ill intent on all fronts, but this entire debacle seems to have resulted from a series of incongruences or miscalculations: Coachella, initially, booking Frank for a headline slot, knowing the introspective qualities of his oeuvre and previous festival performances, without some kind of contingency plan in place, and some kind of production error or miscalculation (or apathy) on Frank’s part along the way as well. Coachella did not refund tickets, and were able to book a replacement act: Fred again.., Skrillex, and Four Tet, for the following week, which went down well, even if it didn’t placate Frank fans.

The reality though, for many others in the crowd, renders all this discussion moot. Many of them spent outrageous amounts of money to attend the entire fest in the hopes of seeing their one favorite artist, who, outside of a string of nightclub events in NYC in the winter of 2019/20, has not performed in quite a while. Whether heading out to the desert and attending all of Coachella just to see Frank was a prudent decision or not for most, it speaks to the almost religious power artists, and Frank in particular, hold over their audiences, and to what extent they must manage audience expectations, and are responsible for delivering in accordance with them. Frank’s audience remains well within their rights to be disappointed by the performance.

Far behind the health and well-being of the audience, there’s another issue at play: what Frank’s performance might have meant for dance music specifically. Giving the incredibly talented Paris-based DJ Crystallmess an opportunity to rip Jersey club and Sango remixes of his songs on a divinely-appointed set of CDJs, designed by the late Virgil Abloh, on the biggest stage at the most name-recognizable music festival in America, should have been seen as somewhat of a monumental accomplishment for the artist, subgenre, and dance music in general, if not for everything else that surrounded it. The PrEP+ and Homer Radio ventures, which influenced this performance, are both steeped in the queer history of dance music, and the Crystallmess interlude at Coachella fits well within this vein. It was meaningful in this respect, but was far overshadowed by the broader public discourse surrounding the performance in its entirety.

Coachella’s choice to release the entire recording of Frank’s replacement act from week 2, a b2b2b between Fred again.., Skrillex and Four Tet on YouTube, seems as much a mea culpa by Goldenvoice as it is an honest endorsement of this particular set: publishing the set seems a convenient way to distract the headlines from the lingering controversy surrounding the still-enigmatic Frank Ocean performance. OMG TBA delivered a significant set, sure, but the saviorism attached to the whole thing by fans in the comments and press feels strange. It’s DJs closing Coachella’s main stage, but it’s not an underdog story, it’s the biggest festival in the country hastily booking a safe bet with much lower production costs. The festival-sized remixes of pop songs that dominated the 90 minutes reflected its status as an exemplar of dance music commodification, not culture.

Coachella seems to be in the midst of a certain identity crisis as it truly becomes one of the pre-eminent institutions in the music industry. The booking is absolutely top-tier, but something about it is clumsy in its excessive, gargantuan scale. It’s all an unnatural struggle, in this massive complex built up and torn down over and over, every year, at the drought-ridden edge of the desert in Southern California. It’s just not an environment that’s naturally conducive to human life. In the end, the desert is going to win, but in the meantime, at Coachella, the house always wins.

David McGraw is a freelance writer and photographer, follow him on Instagram