Features

Features

Dance music should be wary of posthumous releases

The ethics of posthumous releases is a contentious subject

In the 2003 documentary Living with Michael Jackson, the King of Pop is fondly admiring a golden sarcophagus when presenter Martin Bashir asks him: “Would you like to be buried in something like this?”. MJ giggles uncomfortably, as if affronted by the question. “No, I don’t ever want to be buried,” he says, “I would like to live forever.”

Although his ambition for immortality is absurd, watching the clip back now, nine years on from Michael Jackson’s passing, is a macabre experience. In part because he possessed talent so rare and so deified that his fanbase could find themselves beguiled into thinking that perhaps this man would defy the foremost law of nature.

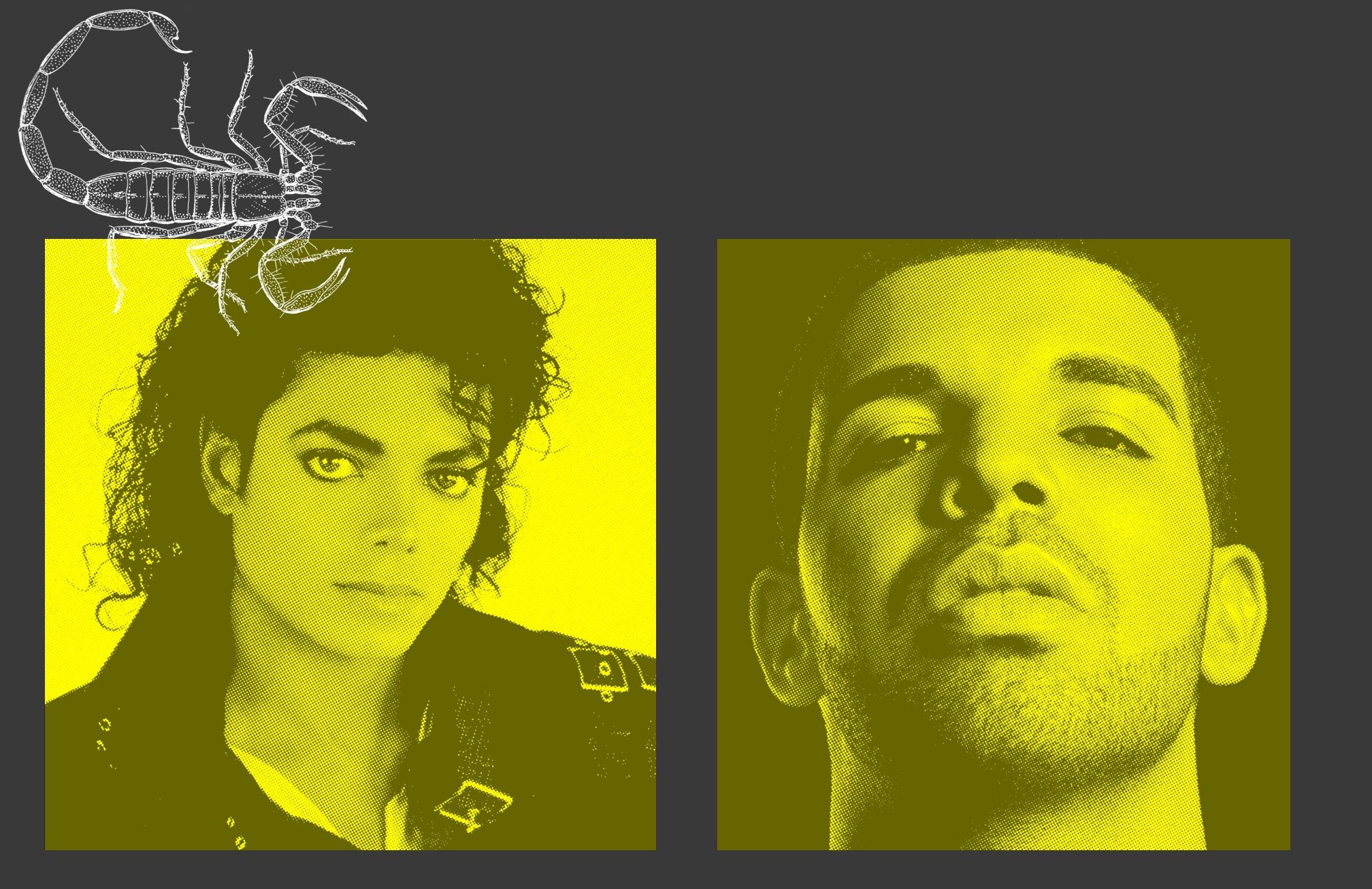

Of course, this talent has immortalised Michael Jackson in some sense, which he knew. Another of his famous quotes reads: “Music has been my outlet, my gift to all of the lovers in this world. Through it, my music, I know I will live forever.” Leaving a mark with the hope of being remembered when you’re gone is a recurring existential drive of humanity. It motivates people to carve their names into rock faces, or fasten padlocks with inscriptions to bridges. And the hundreds of millions of records MJ sold in his lifetime have laid down an unforgettable legacy. But it’s a drive nurtured by ego, as much art is. Concerned equally with one’s peace of mind while living as the intangible hope for post-mortem impression. It refers to life’s intentioned work prevailing after death. Which is why it felt uneasy hearing a canned MJ vocal from a 1983 session raided for inclusion on Drake’s recent ‘Scorpion’ album track ‘Don’t Matter To Me’.

Drake has been plagued with accusations of employing ghostwriters throughout his career, but his Ouija board summoning of MJ took this to a particularly unsavoury and literal level. When Jackson spoke of living immortally through music, it’s hard to imagine that a vocal he deemed unworthy of release being bodged onto a tepidly received album, by a rapper still stinging from a recent bodying at the hands of Pusha T, is what he had in mind.

Raiding the vaults for cutting room floor scraps that an artist didn't choose to release in their lifetime is one of the ethical dilemmas posited by posthumous releases. Artistry is held in such singular regard that diluting it can often feel disrespectful. The response from Kanye West fans who loved the lauded ‘The Life of Pablo’ but hated the panned ‘ye’ was along the lines of “Kanye really fell off”, not “Kanye’s double figure-strong team of writers, producers and studio engineers really fell off”. No matter who works on a track, the lead name/s stamped on the artwork or written in the streaming platform’s artist column is where the criticism is heaped, be that praise or flak. It can come across as unjust to release music bearing the name of someone who has not signed off on it.

Such releases are nothing new in the music world. There are some heralded as classics: Joy Division’s ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’ arrived a month on from Ian Curtis’ suicide; ‘Buffalo Soldier’ came out two years after Bob Marley succumbed to skin cancer; Aaliyah didn’t live to see her single ‘More Than a Woman’ debut at the top of the UK singles chart to critical acclaim. Others were not received so warmly. Universal Music CEO David Joseph destroying Amy Winehouse’s third album demos in a noble bid to prevent an unfinished version seeing the light of day didn’t stop her collaborators cobbling together the inessential ‘Lioness: Hidden Treasures’; a new George Michael single last year felt cheap and half-baked; and barrel scraping has come to dominate the discographies of Tupac and Biggie, who have been more prolific in death than they ever were in life.

Many of these artists were hugely popular in their time, driving the clamour for new material thereafter. Now in 2018, as EDM stands among the planet’s most popular styles, the sad death of Tim Bergling aka Avicii looks set to be a prelude to electronic music’s first posthumously exploited superstar.

Avicii’s A&R started talking up the Swedish artist’s final work in progress material as “his best music in years” and mulling over its potential release mere days after the 28-year-old took his own life. This is grim. The raft of health problems Avicii suffered in life that contributed to his demise have been attributed to the intensity with which he was pushed into money-making activities by people in the industry who were meant to look out for him. His step-father Tommy Körberg blamed mismanagement for pushing Bergling towards suicide. “You do not book 900 gigs in eight years for a young man,” he said. ““If [Avicii] had a professional artist company, he would be alive today.” The signs were explicit, and 2017 documentary Avicii: True Stories makes for morbid viewing. “I have said, like, I'm going to die,” states Bergling bleakly on camera while airing frustrations about his manager’s refusal to scale back his touring schedule. Then not even a week after his tragically inevitable death, an industry figure is promoting his prospective new album. Capitalism drove Avicii to end his life, and before his body had been laid to rest the cogs for wringing more profits from the remnants of his talent were already turning.

Even if you argue that fans will want to hear this music, the timing of these comments was insensitive in a period that should have been reserved for mourning, not hyping. And the industry knew it. A month later reports of a posthumous album built from a bank of nearly 200 finished songs were swiftly denied, but now signs of an incoming project are trickling through. In August regular collaborator Carl Falk unveiled a cleaned up and finished version of Avicii’s previously unreleased demo ‘Heaven’ and wrote in a since-deleted Instagram post that he felt “strange and emotional” finishing these “songs” - plural. I’m not certain where the money from a new Avicii LP would go, but the possibility that people in the industry who bear responsibility for Tim Bergling’s death could continue to have their pockets lined by his music is deeply sinister. Nicky Romero, upon revealing he is in possession of multiple folders of unreleased and unfinished Avicii material, said: "I don’t know if it morally feels right to me to work on songs that the original composer has not approved. I know that Avicii was really a perfectionist, and I kind of feel bad if I put something out not knowing if he wants to put it out.” If a new Avicii album arrives, fans will have to make a similar moral judgement on whether to support it.

There is no absolutist rule on what makes a posthumous releases acceptable or not. Considered judgement is key in the difference between a record that feels celebratory and one that feels distasteful. The Marcus Intalex Music Foundation was founded by the drum ‘n’ bass legend’s friends and family, aiming to inspire new generations of musicians with community projects and experts providing education. Proceeds from his posthumous releases are being directed to the cause. Peers of Marcus praised his willingness to share knowledge and help budding artists in life, so this is a positive way to preserve his legacy and helping to fund it through his music makes sense. The Teklife crew owned banks and banks of unreleased DJ Rashad dubs that were regularly played in their club sets, and many of the releases he did put out were collaborative. This material being worked on and released by the peers he called family for the 2016 ‘Afterlife’ LP doesn’t feel disingenuous to his vision in the same way as Drake plucking the discarded vocal of a man he never knew.

Problems seems to be most prevalent when there's big money to be made. Even when artists have full creative control on a posthumous release, the sales spike that often greets their death (sales of Prince’s ‘The Very Best of Prince’ rose by a colossal 70,000 per cent in the week after he died) can be troubling, such as in the case of XXXTentacion. A court deposition from his ex-girlfriend Geneva Ayala recounted horrific details of torturous abuse the rapper subjected her to, including beatings, daily death threats and vowing to cut out her tongue for humming the verse of a featured rapper on one of his tracks. Before XXXTentaction was gunned down in June of this year in what police described as a violent robbery, he had finalised the release rollout for a new single ‘SAD!, including writing and creative directing the video. News of the Floridian rapper’s abusive behaviour helped him build a fucked-up following during his life, including in alt-right circles and multiple co-signs from Milo Yiannopoulos, with his popularity booming after he was sent to jail. In death this surged again: in the same month he was murdered ‘SAD!’ became the first posthumous Billboard Hot 100 chart-topper since Biggie in 1997 and his latest album ‘?’ saw a 41,306 per cent spike in digital sales. There’s another disturbing element and dangerous precedent to profit being reaped from an abusive artist, and then furthermore the artist’s violent murder. News of an upcoming collaboration with the also deceased rapper Lil Peep indicates X’s brutal gravy train is moving full steam ahead

At the point where two rappers who recently died untimely deaths in their early twenties are collaborating on new material, the whole situation is so shocking and grisly that it's clear something has gone seriously wrong in the music industry.

Lil Peep is another troubling case. He died from a drug overdose last November shortly after posting video clips on social media in which he dropped numerous Xanax pills into his mouth. A video for his second posthumous single ‘4 GOLD CHAINS’ was released in May, in which he is also shown taking Xanax. Even if this maintains an authenticity to Lil Peep’s artistic image, it oversteps the mark into ghoulishness, and it feels irresponsible to continue to depict the self-destructive behaviours of an artist when such actions led to their death. Especially an artist with a largely young and impressionable fanbase such as Lil Peep.

Another of dance music’s EDM superstars, Marshmello, was criticised for releasing the posthumous ‘Spotlight’ collaboration with Lil Peep. He defended his decision, saying Lil Peep’s mother Liza Womack wanted the track to come out. She shared an excerpt from one of Peep’s school essays alongside the track, reading: “In my life I find [cultural resistance] very important and vital to me growing as a person, because my art will always grow with me. If someone were to limit the growth of my art and ideas, I wouldn’t be able to express who I am the way I want to.” The explicit mentions of his life and wishing to maintain agency on his artistic growth in the essay strike me as reasons to not release posthumous material. The catalogue of an artist like Lil Peep, whose sound is so cutting-edge and contemporary, also runs the risk of quickly sounding dated as trends progress.

And that raises another point. Dance music prides itself on its futurism and strive for innovation. Earlier this summer Donna Summer topped the Billboard Dance Club Songs chart for the 16th time, six years on from her passing, thanks to Ralphi Rosario and Erick Ibiza releasing an updated version of her 1979 hit ‘Hot Stuff’. David Bowie swept the best British male and best British album gongs at the 2017 BRIT Awards for his ‘Blackstar’ album, released two days before his death, in categories featuring Skepta who spearheaded grime’s thrilling charge to the mainstream. It can be sad to let go of favourites of the past, but if classics keep getting rehashed dance music risks becoming dominated by unoriginal and dated ideas.

There is a time and a place for posthumous releases, but we should ensure we don’t exploit those no longer with us in our hunger for unheard material, and not let them distract from the working pioneers that deserve championing today. We should focus on letting the dead rest, and the living live.

Patrick Hinton is Mixmag's Digital Staff Writer, follow him on Twitter