Features

Features

The 50 most influential dance music albums of all time

Electronic music wouldn't be the same without them

Dance music is great isn't it?

We've experienced not only a wealth of incredible electronic music over the last 40 years or so, we've seen it spur on cultural movements and define the lives of generations. From the Summer Of Love, where acid house and ecstasy reigned supreme, to the birth of techno in light of political and social oppression.

How can you forget UKG rearing it's mischievous, bumping head or even that behemoth they call EDM taking over the minds of millions around the world.

Whatever your preference, we've been truly spoiled and when it comes to albums, there have been some true cornerstones of relevance that have not only got us dancing, but inspired and influenced the next wave of artists to bring forth something, new, exciting and progressive.

Here we present the 50 most influential dance music albums of all time, no easy task to compile as you can imagine. We called upon our bursting pool of contributors from over the years and our trusted members of staff to give an accurate representation of electronic music's evolution over the last four decades.

Here we go...

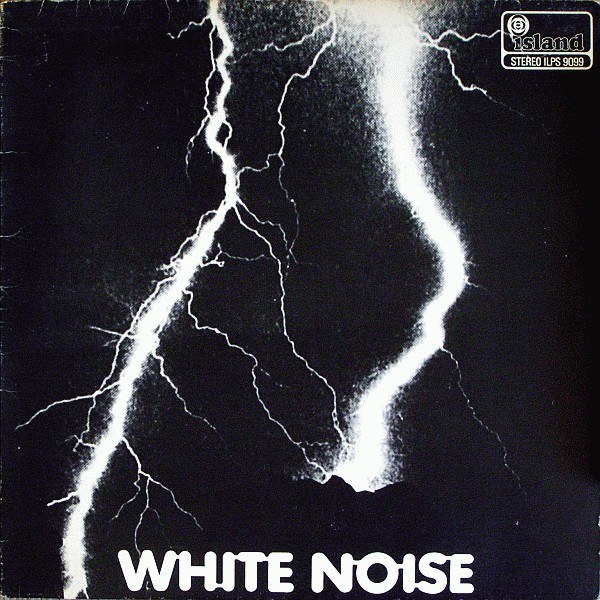

White Noise 'An Electric Storm' (1969)

There were plenty of awesome talents in the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, many of whom are still creating strange and wonderful electronic sound to this day. But the one who most captured other electronic artists' imaginations is the late Delia Derbyshire. Most famously with the original Dr Who theme, she brought avant-garde recording techniques and delirious sonic abstraction right into the heart of mainstream Britain's living rooms.

In her lifetime, she didn't get the appreciation in her own right that she deserved – but she did get a moment somewhere near the limelight when she and fellow Radiophonic Workshop toiler Brian Hodgson were recruited by American electronic engineer David Vorhaus to try and use their techniques to make a “pop oriented” record. 'An Electric Storm' is hardly pop: it's a brilliant and demented melange of easy listening, cosmic sex scenes, occult weirdness and synthesiser swooshes, in one sense pure Austin Powers 60s kitsch, in another utterly futuristic. Certainly you can hear its blips and shimmying all the way through Broadcast, Boards of Canada, Stereolab, and even Flying Lotus and Madlib – and its giddy dreams of the future are still highly playable in their own right. Joe Muggs

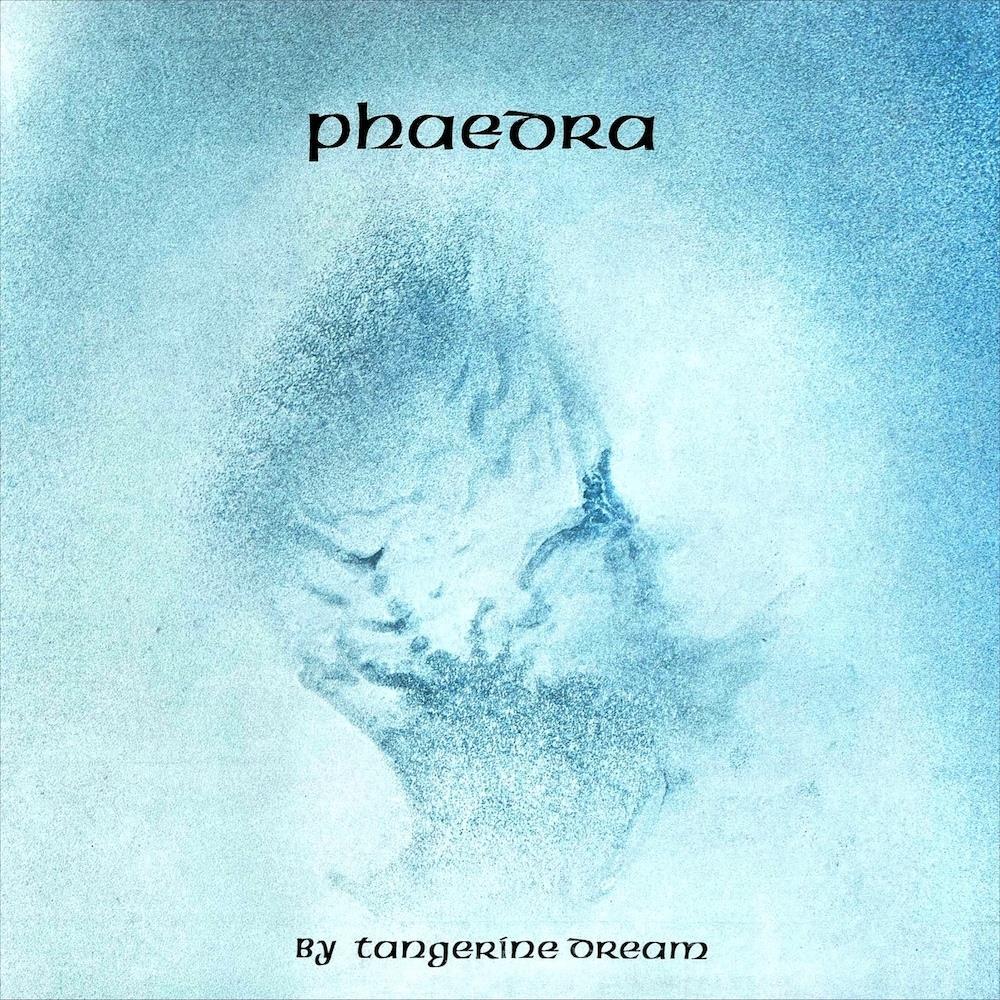

Tangerine Dream 'Phaedra' (1974)

Others from the Krautrock movement of the 1970s have had their influence on electronic/dance music for sure: Can's breakbeats and tape manipulation, Faust's sample abuse, Ash Ra Tempel spawning Klaus Schulze and ‘E2-E4’, and of course the world-bestriding robots, Kraftwerk. But Tangerine Dream deserve a special place in history for their discovery of how to switch off gravity in this 40-minute musical levitation. There were pure synthesiser records before this, from both academic composers and underground heads, but this was the one that perfectly captured that sense of music that takes you back to the womb.

The genius was to make every sound blurred, unfamiliar, so free from unconscious reference points the mind has no choice but to either reject the experience or go along with it completely. Scale becomes confused, you float off into the sound, and time ceases to exist. Brian Eno would codify ambient some years later, but this was it created from pure instinct: closer to what the teenage Aphex Twin would do at the start of the 90s than anything of its time. The world is full nowadays of drones, dreamscapes and beatless sound sculptures – but whatever they may present themselves as, chances are they've got a little of this in them. Joe Muggs

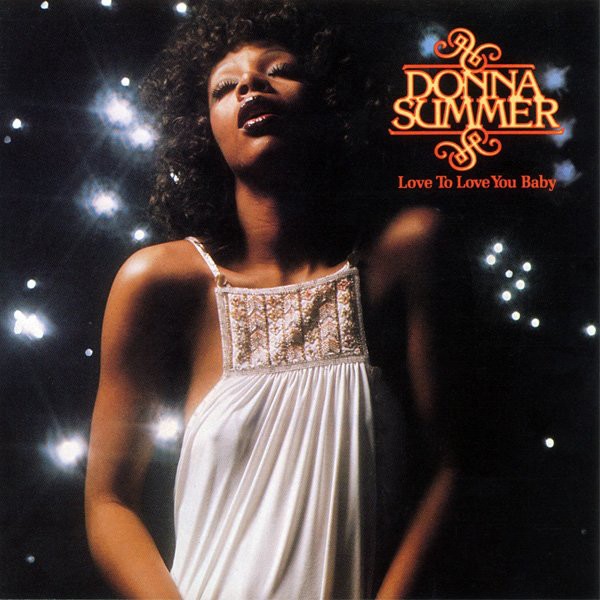

Donna Summer ‘Love To Love You Baby’ (1975)

The song from which a thousand dancefloor samples were launched, ‘Love To Love You Baby’ is undeniably the stand-out track from Donna Summer's 1975 album of the same name. Summer's second studio album’s title track was initially released with little fanfare as an abridged 3-minute track, before Italian disco legend Giorgio Moroder had an unexpected brainwave: Summer should simulate orgasm throughout its extended, near-17 minute long run time.

One of the greatest disco tracks of all time, Summer's orgasmic whelps inspired a generation of producers: you can hear her influence in the moans that pepper Lil Louis' ‘French Kiss’ over a decade later, helping to birth house music. But there's so much more to the album than this sinuous, sexy disco cut. The rest of the album is pretty killer — hold tight for ‘Need-a-man-Blues’, a jaunty Moroder-written Italo track that has a way of looping around in your brain way after the initial run time is over.

Summer's contribution to wider dance music history shouldn't be passed over. In particular, Summer helped pioneer the use of electronic sequencers and electronic drums in dance music. Prior to ‘I Feel Love’, dance music had been about funk: the idea that machines could make songs was relatively unheard of. Then along came this smooth, machine-like sound with Summer's shimmering vocals overlaid on top, and dance music was transformed. Without Summer (and other contemporaries, like Kraftwerk), making this sequencer-led machine-made music, we wouldn't have techno, or most other subsequent dance music. We owe Summer an enormous deal, even if her legacy is somewhat underrated. Sirin Kale

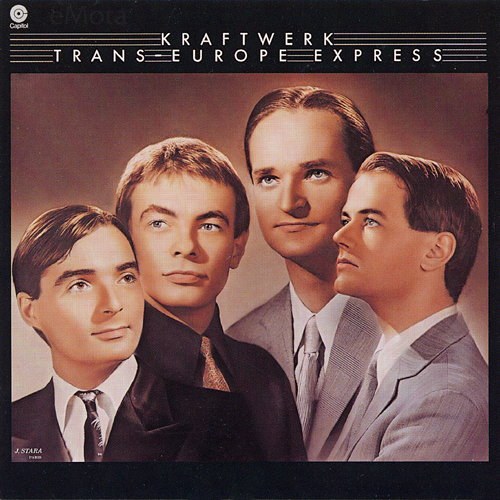

Kraftwerk ‘Trans-Europe Express’ (1977)

It’s difficult to know where to start with this one. It’s hardly an exaggeration to say Dusseldorf four-piece Kraftwerk laid down the blueprint for all that followed. They were the first to make popular music purely from machines. They invented electro-pop. And if minimalism – as in, repetition and simplicity - is one of the keys to house and techno, Kraftwerk first brought it in from the world of modern classical. On ‘Trans-Europe Express’, before anyone else, they defined what electronic music could be.

It consists of eight tracks that beautifully showcase a pared-back, sequenced economy of sound, the most famous song being the title track and ‘Showroom Dummies’, which revel in Kraftwerk’s deadpan, robot aesthetic. But there’s also the proto-techno of ‘Metal On Metal’ and the luscious ten minute beauty of ‘Europe Endless’. In America they were listening. Afrika Bambaataa’s ‘Planet Rock’, a founding stone of hip hop, was a rejig of ‘Trans-Europe Express’’s title track. In Detroit Juan Atkins’ seminal electro number ‘Clear’ directly referenced Kraftwerk’s ‘Hall of Mirrors’. In the UK a whole wave of ‘80s electronic pop stars, from OMD to The Human League, acknowledged a debt. From these early breakthrough artists the music Mixmag covers was mostly built. And there at the start of it all was ‘Trans-Europe’ Express’. Thomas H Green

Parliament 'Funkentelechy Vs. the Placebo Syndrome' (1977)

Perfection comes in many forms, but not many are as technicoloured and damn weird as Bernie Worrell's Moog notes in ‘Flash Light’, the track that closes off this album. The whole thing is all killer, no filler, even when tracks extend to ten and eleven minutes: this is essentially George Clinton's p-funk mob at the height of their powers – Bootsy Collins basslines swinging and swaggering through the 10-dimensional afrofuturist cartoon vision, every part of the band including massed vocalists and brass locked in with inhuman precision.

But Worrell takes it even further, subtly at first, then on ‘Flash Light’ with total abandon. In his swoops and blurts, blips and bloops, you can practically hear techno and electro being born. Never mind Derrick May's “techno is George Clinton stuck in an elevator with Kraftwerk”: it's Bernie, pure and simple. He's banging the future out of his keys. Obviously dozens of hip hop artists from Tupac and Snoop on down owe this record their lives, too – but so does anyone who's ever twiddled a keyboard modwheel, from Daft Punk to Dorian Concept, Terror Danjah to Flying Lotus. Innovation has never sounded so fun. Joe Muggs

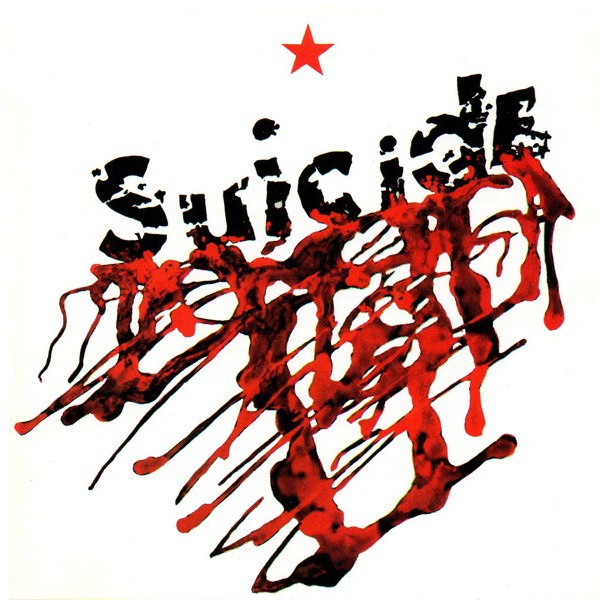

Suicide ‘Suicide’ (1977)

Suicide's eponymous 1977 album feels as fresh and red raw as a recently acquired hangover: it pounds in your brain from storming opening track ‘Ghost Rider’. Nothing about this album is straightforward, even if the production values aren't exactly sophisticated.

Suicide's trademark use of minimalist electronic instrumentation not only helped birth post-punk, but electronic music also. It's not all angry, disaffected post-punk though: the tinkly, delicate synth on ‘Cheree’, paired with a steadily increasing drum track, gives the tune a lullaby-like quality, like a 50s love song made sinister by distortion and repetition.

And we can't underestimate the album’s impact on subsequent dance music. You hear traces of 80s new wave in the opening bars of ‘Keep Your Dreams’, an earlier incarnation of ‘Dream Baby Dream’, the maudlin, moving track recently sampled by Adam Curtis to great popular acclaim in documentary Hypernormalisation.

‘Suicide’ is often antagonistic, barely contained sound—probably seen to its most disturbing effect in Alan Vega's bloodcurdling screams at the end of murder anthem "Frankie Teardrop"—is fun to analyse and pore over. Here's traces of no wave; here, techno. But Suicide is a great album because it marries difference: it has the polish of a studio album, but the energy of a live performance; it marries expressionistic vocals with scanty, thudding electronic instrumentation. Best of all? It's deeply weird. Sirin Kale

Brian Eno ‘Ambient 1: Music For Airports’ (1978)

There’s a case for a number of Brian Eno-graced records to feature on this list; the space-age synths of David Bowie’s ‘Low’ and polyrhythmic funk of Talking Heads’ ‘Remain In Light’ spring to mind first. But for Brian Eno’s biggest contribution to electronic music look no further than the time he invented ambient music, a style that has since sunk its teeth into all aspects of the scene. The self-described ‘non-musician’ had toyed with sparse, quiet and calming sounds on albums like ‘Discreet Music’ and ‘Another Green World’ before. But it was here, on ‘Ambient 1: Music For Airports’, he helped define the genre as we know it today – it was also the first usage of the word “ambient” in a musical context.

Dripping in scarce, wandering synths and soft, digitised choral voices, ‘Ambient 1’ lulls the listener into aimless relaxation over four solemn soundpieces. The album has soundtracked many of my morning-after meanderings and scrambled article writings. But its influence goes beyond soothing a sore head. Eno’s fingerprints can be found in the chill-out music that came to define backrooms during the 90s, the records of IDM’s golden boys Aphex Twin, Oval and Autechre, and what would a RØDHÅD record – or countless other modern techno records – sound like with all their dark ambience removed? Eno’s influence on electronic music is irrefutable and, on this record, helped set the tone for a softer side of dance music for generations to come. Charlie Case

Patrick Cowley ‘Menergy - The Fusion Album’ (1981)

‘Menergy’ drove dance music forward on an exultant wave of intangibles and precision, capturing the spiritual essence of the birth of clubbing culture in a set of meticulously-crafted tracks. In the 70s, Moroder and Summer’s ‘I Feel Love’ sparked the beginnings of hedonistic rave, and as the decade turned, Patrick Cowley’s Hi-NRG masterpiece signalled disco morphing into the ‘dance music’ phenomenon that has endured ever since. Making lyrical references to same-sex attraction and bathroom hook-ups above glistening production, it’s an unabashed celebration of the gay scene that forged the culture, crackling with the vibrancy of the dancefloors housed within nightspots’ X-rated walls.

Cowley devised numerous technical innovations to achieve this dazzling sound. John Hedges, who for a time ran the Megatone Records label Cowley founded alongside Marty Blecman, described Cowley’s apartment as a “mess of wires” that “didn’t look very safe”, commenting on the intricate and ingenious patching experiments Cowley undertook to achieve his range of synth sounds, long before you could just turn a dial on Ableton to add delay. The LP’s title-track also contains a production trick wherein the bass drum is momentarily cut out before returning in full force for some added kick - a technique later popularised as “the drop” and repackaged in sterile, commercial releases that are a million miles from the revolutionary vitality of ‘Menergy’.

Cowley tragically died in the year after the release of the record, an early victim of the AIDs epidemic that decimated the original creators and appreciators of dance music. His later album ‘Mind Warp’, written in his death throes amid a rapidly deteriorating condition, was slower and darker, containing track titles like ‘Mutant Man’. But ‘Menergy’ arrived before Cowley’s diagnosis, and provides a dynamic snapshot into the freewheeling, unabashed energy that partying and then house music were built on. It continues to stoke creative fires and artistic intrigue today, with the likes of Pet Shop Boys and New Order citing Cowley as a significant influence, and labels such as Dark Entries and Macro contributing to a spate of posthumous reissues and unearthed releases. Patrick Hinton

ESG ‘Come Away With ESG’ (1983)

Not many bands can boast that they got picked up by Tony Wilson for Factory Records, played the closing night of Paradise Garage and have been sampled by the likes of Biggie, Dilla and TLC. But then, most other bands didn’t come up in New York in the early 80s, when no wave, disco and hip hop were the heartbeat of the city.

ESG – made up of sisters Renee, Deborah, Marie and Valerie – embody this coalescence of sound. Their approach is resolutely minimal, stripping things back to the essentials (fat basslines, taught percussion, angular melody and repetitive vocal chants) to create a highly-charged sound that’s way more than the sum of its parts.

‘Come Away With ESG’ is their debut album, a wonderful primer to their raw, sultry style, which would go on to set the blueprint for the New York punk-funk scene some 20 years later. For without the Scroggins sisters, there would be no LCD Soundsystem, Rapture or Le Tigre. And similarly, later in the 00s and over in Europe, no nu rave explosion (see: Klaxons, Shit Disco or any of the bands released via Kitsuné). They, alongside peers Liquid Liquid and Bush Tetras, were the first to take up instruments to create a new interpretation of “dance music” for which all indie-disco kids, past and present, must give thanks. Seb Wheeler

Arthur Russell ‘World Of Echo’ (1986)

Like an earlier entrant on this list, Patrick Cowley, Arthur Russell was a world-changing genius taken too early by the scourge of AIDs. Passing a full decade on from Cowley in 1992, Russell’s death is symbolic of the Reagan presidency’s homophobia-fuelled policy of near-total inaction through the 80s (audio tapes emerged in 2015 of the administration laughing and making homophobic jokes during briefings on the crisis). Despite the oppression they faced on an institutional level, the queer community persevered as a vital source of creative inspiration. Russell was a true trailblazer, so far ahead of his time that music is still catching up to his developments. Like many innovators, he was sadly underappreciated in his time, dying in relative anonymity and poverty. But posthumous focus his work and the archives he left behind has been extensive, establishing Russell as an all-time great. His legacy can be found all over, from the label Audika Records set-up solely to release his catalogue of experiments to the spate of club nights and music projects named after his output (such as Lucky Cloud, Kiss Me Again, Wild Combination, Let's Go Swimming and Jame Blakes’s 1-800-Dinosaur outfit) to an endless list of artists sampling his music, including Kanye West for ‘The Life Of Pablo’ cut ‘30 Hours’.

Russell was a perfectionist who struggled to consider works finished, relentlessly tinkering with tracks and making numerous versions. When he did, though, the results were exquisite, and his 1986 album ‘World Of Echo’ is an unquestionable masterpiece. Recorded using just a cello and his voice, which he manipulated with a whole host of electronic effects, its impressively diverse tracklist can be pointed to as the prototype for many styles of electronic music that followed. Rhythms take centre stage through ‘World Of Echo’, simple strums and complex, interlocking arrangements propel the record forward with a percussive-like energy that it achieves without any drums. The forefronting of strings in an LP of peculiar electronic-pop hybrids is a precursor to Dev Hynes, Dean Blunt, Owen Pallett and Sufjan Stevens. Tonally, the mood is impossible to pin down, rooted in a reverb-soaked melancholy but endlessly exploratory and playful, hitting at a kind of gloomy-euphoria that the likes of New Order, Frank Ocean and more recently Yaeji have achieved considerable success with. ‘Lucky Cloud’ underpinned weird, high-pitched squeaks with bold, driving bass notes long before minimal rose to prominence; ‘Hiding Your Present From You’ throbs with experimental club flair, as stunted outer textures cut through from off-kilter swells. Even his constant revising of analogue compositions seemed to predict the age of production software tweaks and folders of Ableton files titled ‘Version 87 final (V3 edit)’. Fearlessly innovative, Arthur Russell laid the groundwork for genre boundaries and simultaneously broke them before they existed. Patrick Hinton

Mr Fingers 'Amnesia' (1988)

It's 1988 and the name on the street is Jack. House music is bubbling fervently in the Chicago underground while being systematically ignored by the mainstream, and the first sounds are slowly drifting their way over to the UK. But a young Larry Heard wasn't feeling 'Jack'. In fact, on the sleeve notes for 'Another Side', he told Simon Witter: "Jack means nothing to me. Our songs are about experiences and belief." By staying true to his vision, and armed with just a Yamaha DX7, Roland Jupiter 6 and Tr707 drum machine, Larry Heard gave birth to an entirely new subgenre: deep house. To be honest we could stop right there. That fact alone tells you how hugely influential Heard has been on dance music.

Where his peers borrowed from disco, the southside Chicagoan borrowed from jazz and in the process created timeless tunes that still absolutely bang in the club. His debut album 'Amnesia' sums this up best. The record kicks off with 'Can You Feel It' for fuck's sake, the tune that not only made 7th chords the go-to but also contains a bass sound patched into practically every soft synth ever made. Then there's the acidic funk of 'Washing Machine', the drum machine workout that is 'Slam Dance', 'Bye Bye' with it's lounging jazz piano copied by countless Italian producers in the early 90s and of course 'Mystery Of Love'. In 2016 the track was sampled by rap megastar and fellow Chicagoan Kanye West, proving the album's influence on not only every deep house track ever made but also one of contemporary music's biggest stars. Louis Anderson-Rich

The Orb ‘The Orb's Adventures Beyond The Ultraworld’ (1991)

Dance music is about hitting ecstatic headspaces in the feverish pits of dancefloors, certainly, but it’s also about what comes after. Blankets, sinking into sofas as the sun rises, zoning out to ambient mixes. We owe many of the blissed-out soundtracks that have soothed comedowns across the years to The Orb’s ambient house masterpiece ‘The Orb's Adventures Beyond The Ultraworld’. Alex Paterson and co built upon the blueprints set out by Brian Eno and pushed ambient into a more dance-indebted framework, imbuing the sounds with druggy, sci-fi narratives, house and techno beats, and reggae influence, forming a visionary new type of intergalactic dub on tracks like ‘Perpetual Dawn’. The scope of the record is magnificent. Recorded with help from 20 musicians across a string of studios and sessions, it unfolds as one continuous piece of music across its two sides and 1 hour 49 minutes run-time, dragging listeners on the metaphysical ‘journey’ that has come to dominate the way people talk about and attempt to craft dance music and DJ sets.

Shifting from bedroom comedowns to bedroom producers, perhaps the album’s most significant impact is the use of sampling. Paterson would listen to hours upon hours of music, as well as setting up devices to make TV, radio and field recordings, and painstakingly select his favourite sounds to incorporate. The Orb’s WhoSampled.com entry is an absolute treasure trove of intriguing references, from Russian radio hosts discussing fish on ‘Spanish Castles In Space’ to the more easily picked out Minnie Riperton vocals in ‘A Huge Ever Growing Pulsating Brain That Rules From The Centre of the Ultraworld’ – a track which became the most requested Peel Session ever following The Orb’s 1989 performance. Paterson took a fiendish delight in the obscurity of some samples, teasing that fans would “die” if they ever found out the origin of certain track elements. His methods shifted the way many viewed sampling, establishing it as a practice with artistic merit that has since become a hallmark of electronic music. Patrick Hinton

LFO ‘Frequencies’ (1991)

In 1990 a fledgling Sheffield-based label named Warp Records released a debut EP from a pair of Leeds Uni students called Mark Bell and Gez Varley, working together under the moniker LFO. The eponymous single ‘LFO’ peaked at number 12 in the UK singles chart, earning each respective party fast fame. In the previous week’s chart twelfth place was held by a F.A.B.’s nostalgic reimagining of 1960s TV theme ‘Thunderbirds Are Go,’ but LFO and Warp injected something fresh and exciting into the public eye. ‘LFO’ was a bass bin-wrecker of a rave anthem, fuelled by a weighty bassline, laser sharp synths, and an anthemic spoken word vocal refrain. To this day it’s still on regular rotation from DJs spanning Skream and Eats Everything to Ellen Allien and Ricardo Villalobos, always spiritually transporting any party back to a raucous 90s warehouse bathed in head-spinning strobes with its unfailing dancefloor potential.

A year later the success of the single was followed up with a full-length album titled ‘Frequencies’. Opening with the distorted monologue asking “House, what is house?”, listing pioneers such as Phuture, Kraftwerk and Mr. Fingers, then presciently declaring “we hope our music will bring everyone a little closer together”, the record barrels into ‘LFO’ (Leeds Warehouse Mix) and doesn’t let up from there. Across its 14 tracks ‘Frequencies’ distilled the motley spread of styles bubbling up from the acid house movement into a searing hybrid of mutant rave potency. But not just a collection of unevenly stitched together bangers, it’s a proper headphone-rewarding and coherent long player, exhibiting technical prowess that led to Björk and Depeche Mode recruiting Mark Bell to work on ‘Homogenic’ and ‘Exciter’ respectively. And arriving soon after the Second Summer of Love, in a time where dance music was still viewed with an air of contempt by Serious Music Fans dismissing it as craze without staying power, ‘Frequencies’ vindicated dance music as an album compatible art form, laying the groundwork for Warp’s rise to legendary status and the game-changing experiments from the likes of Aphex Twin, Autechre and Boards of Canada that followed. Patrick Hinton

Massive Attack ‘Blue Lines’ (1991)

As the 80s turned into the 90s, sample culture meant taking the music of the past to craft something entirely new became one of the dominant forms of modern music. And perhaps no one did this more elegantly than Massive Attack. On ‘Blue Lines’, the collective which formed out of the ashes of Bristol’s Wild Bunch soundsystem plowed formative influences like soul, dub reggae, the film scores of Enio Morricone and punk rock spirit to create a heady brew that acted as an intrinsically British (and more specifically Bristolian) counterpoint to US hip hop. Although the term was not commonly used until a few years later, the album almost singlehandedly invented the genre of trip hop and at a time when the early euphoria of acid house was turning into the frantic sugar rush of rave, showed that dance music could exist at a much slower and more meditative pace.

‘Blue Lines’ influence can be seen scattered all over the 90s from records by the likes of Portishead and Björk that it helped pave the way for, to much of Madonna’s late 90s output. But what strikes you listening back today, nearly 30 years on from its release, is just how fresh it still sounds. ‘Safe From Harm’ could easily be a cut from the new Kelela record while the Issac Hayes sample brilliantly employed on ‘One Love’ would make a great centerpiece for a brand new TNGHT track. Then you have to remember how inventive the make-up of the group would have felt in 1991. Albums made by bands with revolving line-ups and guest stars from all corners of music are de jour these days (Gorillaz, Major Lazer and Everything Is Recorded spring to mind), but three lads from Bristol with interchangeable roles and guests like Horace Andy would have felt pretty radical in 1991. And in ‘Unfinished Sympathy’ the group created a record so close to perfect that it almost always features in the upper echelons of best song ever lists. Need I say more? Sean Griffiths

Jeff Mills 'Waveform Transmission Vol. 1' (1992)

Techno as a genre and movement didn’t officially get its title until the release of seminal 1988 compilation ‘Techno! The New Dance Sound Of Detroit’. Previously, Derrick May had been opposed to the tag ‘techno’ - saying “To me techno was the stuff coming from Miami. I thought it was ugly, some ghetto bullshit” - and had wanted to label the music style he, Juan Atkins and Kevin Saunderson pioneered as ‘hi-tech soul’. When listening to the airy bliss of May’s ‘It Is What It Is’ or anthemic euphoria and bouncy beats of Saunderson’s ‘Big Fun’, it’s clear that the sounds featured on that groundbreaking comp are more soulful than the unrelenting darkness of techno you might hear in, say, a Berlin club today.

Jeff Mills’ debut album 'Waveform Transmission Vol. 1' was instrumental in pushing techno towards the raw, hard-edged direction it has taken. From the opening beat the album introduces a tirade of punishing hi-hats and brutal, machine-made noise that continue apace throughout - the true archetype of untz untz untz. Mills showed an intense focus in his pursuit of stripped-back techno trips. He first came up alongside Mike Banks as a founding member of militant techno outfit Underground Resistance, but left in 1992 to pursue his own solo vision. Signing a contact with Tresor Records, 'Waveform Transmission Vol. 1’ landed as one of the Berlin-based imprint’s early releases, setting a ferocious pace for techno that many, especially in Europe, would follow. Patrick Hinton

Aphex Twin 'Selected Ambient Works 85-92' (1992)

The euphoric synth trills and angelic whispered vocals – sampled from an 80s atmospheric vocal compilation – that open ‘Selected Ambient Works 85-92’ have come to be one of the most influential ambient tracks ever. ‘Xtal’ has the floating celestial power that many of Richard D James’ tracks do but it has stuck in hearts and minds the most. If there was a ranking of electronic albums that had soundtracked the most comedowns, ‘Selected Ambient Works’ would be near the top.

Not only did this solidify him as one of the most unique ambient composers around, it also showed his idiosyncratic touch with IDM and acid. ‘Delphium’ was a reflection of the melodic and emotional ambient acid house sound that was very present during the early 90s and informed future records that were to come. It’s somewhat comical that one of the most influential albums for ambient music and acid was recorded on a cassette that was damaged by a cat, therefore giving the original pretty poor sound quality. This was the very beginning of his influence and went on to inspire Squarepusher and Plastikman who have manouvered the 303 in similarly beautiful and manic ways. While Richard D James’ sound here is pretty singular, you can hear traces of it through acid and ambient’s recent past. Aurora Mitchell

Plastikman ‘Sheet One’ (1993)

In 1993 Richie Hawtin was not a one man brand worth millions, with tentacles reaching from high fashion to saki production. In 1993 he was not the Teutonic, flick-haired Ibiza-storming giant of today. In 1993 Richie Hawtin was a nerdy, shaven-headed, bespectacled DJ at the start of his career. However, with ‘Sheet One’ he proved techno could go long form, move away from pure dancefloor, while retaining a stark clubland authenticity. It paved the way for everyone from ‘90s trance artists and acid technoheads to contemporary DJ-producers such as Daniel Avery, Helena Hauff and Umfang.

Created in 48 hours in his Windsor, Ontario, studio on analogue equipment, ‘Sheet One’ emulates an LSD trip, never glued to basic dancefloor drums but always propelling forward on warped, head-frying, fluid grooves that still sound sturdily unhinged today. Hawtin had observed Detroit’s founding fathers of techno at work, their line primarily being 12” singles to move crowds. He was able to strip what he learnt back to its essence on cuts such as ‘Helikopter and ‘Glob’, but was just as at happy pushing off into the stratosphere on zonked tracks such as the delicious ’Koma’ and stunning ‘Gak’. Plastikman would go on to other creative heights but ‘Sheet One’ remains Hawtin’s opening shot and his meisterwerk. Thomas H Green

Björk ‘Debut’ (1993)

“There's more to life than this...” sings Björk part-way through her debut solo record, from the toilets of Nicky Holloway’s Milk Bar nightclub. As hedonistic cheers and Balearic beats occupy the space behind her hushed vocals, it’s a rare moment of self-reflection in the dance music community. It’s easy to interpret ‘Debut’ as a simple love-letter to club culture – following the break-up of her Reykjavík rock band, The Sugarcubes, Björk moved to London in 1992 where she became enamoured with the scene happening in the city at that time. And by enlisting the likes of 808 State’s Graham Massey and Soul II Soul producer Nellee Hooper, she tackled the likes of trip hop (‘Human Behaviour’), house (‘Violently Happy’) and techno (‘Big Time Sensuality’).

But, in true Björk-style, she also drew influence from folk, jazz and pop music, and makes something that sounds like the lost collaboration between Aphex Twin and Kate Bush. Adding sensitivity and a myriad of influences to a party atmosphere, Björk helped redefine what dance music could be and, by taking the record to No.3 in the UK charts, helped legitimise its worth in mainstream eyes. Its influence can be traced to all those who have attempted to push the boundaries of dance music, filtering into the work of Fever Ray, MIA, Gorillaz, and even the electronic-influenced rock of Alt-J and These New Puritans. With ‘Debut’, Björk made an album that not only celebrated house music but also asked artists to demand ‘more to life than this’. Charlie Case

Masters At Work 'The Album' (1993)

As house began to flourish during the early 90s, with many producers focusing on jacking rhythms that took over clubland, the NYC duo Masters At Work were able to stand out by showcasing a distinct contrast of musicality. They took the rhythmic motifs and made them their own with both a deeply soulful and lively essence in their material. That’s not to say other artists at the time didn’t have a similar focus, but one listen to MAW’s debut album aptly titled ‘The Album’ and it’s clear Louie Vega and Kenny Dope wanted to explore it all.

Their vast knowledge was channeled into this diverse range of tracks, which included their own take on hip hop, reggae and of course a core foundation of house. Tracks like ‘I Can't Get No Sleep’ and ‘The Buff Dance’ delivered infectious rhythms filled with energy while their overall sound profile still leaned on the deeper side. Plus ‘When You Touch Me’ and ‘All That’ offer the shimmering nature of the 90s vocal house while various gems like ‘Get Up’, ‘Give It To Me’ and ‘Too Smooth’ offered hard as nails hip hop beats. In its entirety ‘The Album’ embodies the scope and influence of 90s music and is an accurate example of just how prolific Master At Work would become. Harrison Williams

The Prodigy 'Music for the Jilted Generation' (1994)

As the 1990s initially revved up The Prodigy were a much-loved rave act, responsible for whistle posse monsters such as ‘Charly’, ‘Out Of Space’, ‘Your Love’, etc, all gathered on their debut album ‘Experience’. Their live show was a PA wherein producer Liam Howlett’s mates Keith, Leeroy and Maxim leapt about in primary coloured, pyjama-style costumes that made them look faintly like children’s TV characters.

With ‘Jilted Generation’ everything changed. Howlett gave the band an abrasive rock ’n’ roll edge that would immediately flavour what outfits such as the Chemical Brothers were doing but also cast a much longer shadow, providing a template for multiple 21st century acts, including Chase & Status, Skrillex, Pendulum and Noisia. ‘Jilted Generation’ simply spat attitude, from its anti-Criminal Justice Bill cover art to the venom of the lyric “Fuck ‘em, and their law”. Influenced by hip hop and Rage Against The Machine, Howlett combined industrially enhanced breakbeats with occasional bursts of caustic guitar, as on the single ‘Voodoo People’, with the closing ‘The Narcotic Suite’ even including a prog rock-ish flute solo. ‘Music for the Jilted Generation’ was still rave at heart, but it had gained a snarling punk edge. It was a statement album and plenty listened and learned. Thomas H Green

Jam & Spoon 'Tripomatic Fairytales 2001' (1994)

It sounds implausible now, but for the first few years of the 90s, trance was a niche genre, mainly for the real space cadets. And you can hear that here: loved up German hooligans Rolf Ellmer (Jam El Mar) and Markus Löffel (Mark Spoon) fill large sections of this record, especially its opening, with gurgles and burbles straight out of the chillout rooms of rave-hippy clubs like Megadog and Megatripolis. But they were also masters of an instant hook: the blissful ‘Stella’ (included here) had broken out across all scenes, and hinted at huge commercial potential.

Then came this album: as the tracks go on, the tempo speeds up (literally, on the accelerating ‘Neurotrance Adventure’ which follows ‘Stella’, and you can practically hear commercial trance being born, beat by beat – until finally the album's centrepiece ‘Right In The Night’ with Spanish guitar and Plavka's unstoppable pop vocal crashes in, and world domination is assured. After this would come Robert Miles, the conquering of Ibiza, megastar DJs, helicopters and egos, but right here is the point of ignition, the moment the explosion began. And you know what? It still sounds great. Joe Muggs

4 Hero 'Parallel Universe' (1994)

Dego and Marc Mac were there for every development in rave. In 1990 their 'Mr Kirk's Nightmare' marked the shift from summers of love into hardcore, and month by month 4 Hero, Dego's Tek 9 and Mac's Manix pseudonym, and their Reinforced label expressed the extremes of darkness and euphoria as the breaks sped up and things got ever gnarlier. Then, in 1994, just as jungle was fully coalescing from the madness, they dropped 'Parallel Universe', which combined every influence, every emotional mode of rave, and more into a glorious, chaotic, cosmic exploration.

Soul, Detroit techno, electronica, spiritual jazz, and sampling technology pushed way beyond its capabilities all orbited their singular vision creating something that – though moments can sound very much of their time thanks to that sampler abuse – still stands up as one of the most ambitious dance records ever made. Its influence shines not just through drum 'n' bass releases like Goldie's ‘Timeless’ (which Dego had a hand in), but every record since that's dared to put together deep soul with roughneck bass, from the duo's own Detroit heroes through the broken beat scene and on to modern jazz musicians. Joe Muggs

Basic Channel 'BCD' (1994)

Mention German techno in the early 1990s, and you likely thought of furious Cologne acid, the metallic pound of Tresor, and general “Schnell! Schnell!” madness all fuelled by the Communist-era amphetamine factories of the East. But Moritz Von Oswald and Mark Ernestus knew different. They knew that techno was as much about subtlety as rowdy impact and, fuelled by an obsession with the most far-out ad hoc techniques of Jamaica's dub originators, they set about remaking the machine beats as an immersive bath of sound.

Layer upon layer of echo and tape hiss, microscopic surface details made dramatic, and vast waves of bass: it sounded both completely alien and like it had always been there. And it changed everything. Obviously the entire boom-click “mnml” generation of the 2000s took them as a starting point, but perhaps even more so, everything in Burial's misty city dreamscapes – and all the legions of emotional headphone voyagers that have followed in his wake – is an extension of Basic Channel's world of gigantic shapes moving through the fog. In fact, so ubiquitous is their sound pallet now that if you heard this for the first time it could be hard to believe it's a quarter century old. Joe Muggs

Robert Hood 'Internal Empire' (1994)

Techno around the early 90s was in its most fertile, formative and revolutionary phase. It was a sound that acted as a militant rebellion in a heated Detroit, one that was brimming with racial tension and social injustice. Jeff Mills and the Underground Resistance stable lead the charge and brought forth a turbulent sound that’s now one of the most popular in electronic music. You can’t talk about techno pre-1995 without talking about (at length) Robert Hood. Another, albeit later, member of Underground Resistance, Hood soon became the master of stripped back, minimal techno. His debut album ‘Internal Empire’ has a sense of urgency and panic while at the same time feeling carefully considered and formulaic.

As far as debut albums go, Hood’s is one of the best and nearly 25 years later, the tracks still leave their mark on a dancefloor. ‘Minus’ is the anxiety-drenched highlight while cuts like ‘Multiple Silence’ and ‘Home’ showcase alien gurgles alongside clinical progression. The second track is called ‘Master Builder’ and whether Hood knew that this track would come to sum up his musical legacy is unknown. Techno feels like it’s come full circle in 2018. The political climate at the moment is the most fragile it’s been for decades and techno as a form of escapism is more prevalent than ever. In fact, it’s a big middle finger to establishment. We like to think Robert Hood got the ball rolling in 1994 and ‘Internal Empire’ will always be a stepping stone for today’s techno. Funster

Autechre 'Tri Repetae' (1995)

The sound of printers malfunctioning and computers melting might be a nightmare in real life situations but IDM producers such as Autechre turn the stuttering sound of a machine glitching into abstract musical beauty. Their third album ‘Tri Repetae’ quickly became an important cog in the lineage of Warp’s incredible run during the 90s. Its distinctly metallic sound palette was eerie, robotic and weirdly melodic.

No doubt it was ahead of its time when it was released, with the crunching abstract percussion and flashing lasers being a more pervasive influence on experimental music now through labels like UIQ. It has very often been described as a “cold” and “mechanical” album by listeners but there are hints of warmth in the stretches of analogue synths that unfold under the icy surface. This darker, more menacing side of IDM and electro had a different appeal to some of the more emotionally driven records at the time. It has undoubtedly come to inform a lot of the colder and crunchier sides of club music, abstract grime and techno that has been released in the past few years. The record had quicker lasting appeal and impact too, with two tracks, ‘Rotar’ and ‘C/Pach’ manifesting as samples in jungle pioneer Photek’s music. Aurora Mitchell

Shy FX 'Just an Example' (1995)

Jungle – proper full-bore, thousand-break-edits-a-minute, police-sirens-and-barking-pitbulls, murderous-ragga-sampling jungle – was never destined to be an album artform. It just moved too fast in every sense. Forged properly in 1993, by the end of 1995 it was all but dissipated as a dozen new drum 'n' bass forms took over. Mostly it exists now via endless brilliantly shonky compilations, and MC-slathered mixtapes capturing the madness of radio and raves. “Album artists” always tended to the more slick, glossy or ecstatic: see Goldie and Omni Trio, etc.

Somehow, though, Andre Williams aka Shy FX, though still not even legally allowed into clubs as he slipped in under the wire in September of '95, managed the impossible and condensed all that junglist energy into a full-length album. He'd already created scene defining anthems with 'Gangsta Kid' and 'Original Nuttah' (both included here), but showing a furious focus, he managed to build an album that not only maintained the momentum but held together in its own right. All of bass music since – from the crazed breakcore cut-ups of Venetian Snares and co through the bassweight of DMZ to new generationz of London teenagers – owes Shy FX a debt of gratitude, but more than that, he's still applying the same focus to the scene to this day. Joe Muggs

DJ Shadow 'Endtroducing…..' (1996)

DJ Shadow’s ‘Endtroducing.....’ is more than simply an album, it’s a journey through sonic experimentation and musical creativity. Sampling had been popularised by house and hip hop producers in years past, but DJ Shadow’s take on the artform took sampling to a new realm of brilliance and this collection was a groundbreaking moment in electronic music production. Sampling likely wasn’t even regarded as an artform in itself before this time, as it was simply a tool in the production process, but this complete release opened the doors for many to chop up anything they could find.

Most of what the listener hears in ‘Endtroducing.....’ are sounds ripped from various vinyl releases and while the initial reaction may be to categorize this as hip hop, the styles presented range from jazz, funk, soul, drum ‘n’ bass, electronica, trip hop and other forms of downbeat music. Released on Mo’ Wax in 1996, DJ Shadow’s debut full-length is clearly one of the most influential releases to ever grace our ears, breaking through to all listeners with its diverse and imaginative sound profile. Harrison Williams

Moodymann ‘Silent Introduction’ (1997)

For every action there is a reaction, and in the mid-to-late 90s house scene it was Moodymann. As mainstream club music got glossier and glossier, EQd and compressed digitally to within an inch of its life, Detroit’s Kenny Dixon Jr did what he did best: went home and fucked his motherfuckin’ MPC all night long. In 1997, that analog rawness spawned ‘Silent Introduction, a collection of tracks handpicked by Carl Craig for his Planet E imprint and blended together in signature Moodymann style. Diatribes on Detroit imposters and applauding crowds weave through an amorphous being that gave us our first full-length look into the producer’s weird and wonderful world.

While Larry Heard was the stately father figure of deep house, Moodymann announced himself as its twisted uncle who would let you smoke a joint in his lounge before handpicking records for you to listen to. The album’s influence can be seen in the similarly sample-happy stylings of the early French touch scene right through to a breed of European artists that include Detroit Swindle, Max Graef, Fouk, Pablo Valentino – hell, not only does Motor City Drum Ensemble’s ‘Send A Prayer Pt.2’ sound have every single element of a Moodymann track, but his reference is a tribute to the city that KDJ fiercely represents in his music. Only an enigma like Moodymann could have that impact on entire generations of musicians. Louis Anderson-Rich

Daft Punk 'Homework' (1997)

Before the Grammys. Before The Pyramid. Before the robot masks. Thomas and Guy-Man (then only 21 and 22) created The Album That Changed The World. Off the back of two tracks, 'The New Wave' (which would later evolve in 'Alive') and 'Da Funk', the pair were signed to Virgin, through which they released 'Homework' (named because it was recorded in Thomas' bedroom). On the face of it, it was a nod to the dance music world that had come before them but it would go on to write dance music's future. It's become the most referenced album ever in Mixmag to the point where "I was into X until I heard Homework" has become a banned DJ interview cliché.

Producers at the time were convinced it had to have been created using some newfangled recording software, only to discover it was spliced together using an old Roland TR-909 and snippets of Elton John and Barry Manilow records. Tunes like 'Around The World' and 'Da Funk' went on to become global dance anthems while 'Rollin & Scratchin'' and 'Alive' to this day can still send the most hardened techno fans into a jibbering, red-faced mess. On its release Daft Punk told Mixmag that "there is nothing French about our music" despite redefining what was considered French music so well that ‘Homework’ sounds more gallic than an accordion being played on the Champs-Élysées. Younger fans may prefer the more polished and accessible sound of 2000's Discovery. But in terms of being historically influential to human kind, ‘Homework’ is up there with the meteorite that wiped out the dinosaurs. Nick Stevenson

The Chemical Brothers 'Dig Your Own Hole' (1997)

When it comes to assessing The Chemical Brothers’ sizeable influence on electronic music, their biggest impact might be as a live act. And their second album was the one that set them on the path to becoming a globe-conquering festival behemoth. ‘Dig Your Own Hole’ is a heady and maximalist cocktail of chunky beats, funk, acid house, psychedelia and hip hop that spawned two number one singles (The Noel Gallagher featuring ‘Setting Sun’ and ‘Block Rockin’ Beats’) and placed them alongside some of the biggest acts in the world.

By calling in vocalists like Noel Gallagher, and playing concert venues like Brixton Academy to support the album as opposed to DJing in clubs, The Chems were able to appeal to an audience more used to gig-going and guitar music as much as they were able to appeal to the dance music faithful. Some might accuse them of pandering to traditionalists by positioning themselves in the rock world as much as the dance music world, but every act that makes the switch from club DJing to being a touring live act (Bicep and Dusky are two recent examples) owe a debt to The Chems and this album. 1999’s ‘Surrender’ might stand up as the better and less dated album today (the development of production techniques in electronic music moved fast in the 90s), but this album laid the foundation for a thousand dance music festival headline sets. Sean Griffiths

Photek 'Modus Operandi' (1997)

If a pub quiz threw up a question about a game-changing drum 'n' bass or jungle album in the '90s, chances are it'd be Goldie's 'Timeless' scrawled on the result papers, rather than Photek's debut album. 'Modus Operandi' (translated as 'mode of operation') might not be a record those with a casual interest in music are familiar with, but it did signal a significant change for jungle by coming out on Science, the dance-orientated sub-label of Virgin Records. It came three years into Photek's career, in which he'd carved a reputation for producing apocalyptic tracks like 'The Seven Samurai' or hyper-percussive classics like 'Consciousness'.

While jungle sounded like a combination of rigorous basslines and a smattering of percussion sent from the future when it arrived in the early '90s, Photek took the idea of futurism hundreds of years further on 'Modus Operandi'. 'Aleph 1' could be the cosmic soundtrack to whizzing through an unknown world, while the devastating 'Fifth Column' could well signify a tumble down a black hole. Yet in between this there's the serene '124' and suave, Pink Panther-esque title track proving jungle artists aren't only inclined to make tunes for a grotty dance. The album did so well it opened the door for fellow junglists Source Direct to release an album on Science in '99. Dave Turner

Boards Of Canada 'Music Has The Right To Children' (1998)

When two brothers from rural Scotland released an album that twirls through mystic ambient, robotic vocal samples and lightly bobbing IDM in 1998, it changed dance music forever. ‘Music Has The Right To Children’ had incredible crossover appeal. It sat comfortably beside IDM such as Aphex Twin and Autechre but it also conveyed the nostalgic and emotional role that voices have played in bands the duo have been influenced by – such as Beach Boys and My Bloody Valentine.

The duo’s work had been picking up steam with ‘Twoism’ and ‘Hi Scores’ but ‘Music Has The Right To Children’ really opened a new vortex. Through analogue synths and drum programming that was lengthily laboured over, Boards Of Canada created an incredibly emotional sound. This was dance music to make you feel and nearly 20 years on, those memorable technicolour synths on ‘Roygbiv’ are still the gateway to new listeners being introduced to the world of these two Scottish producers. It’s a sound that has been replicated overtly by artists such as Com Truise and Tycho, became one of many basis’ of influence for internet subgenre vaporwave and has inspired many an ambient producer working today. Aurora Mitchell

Air 'Moon Safari' (1998)

While the individual tracks of Air's debut album are intricately crafted gems (the string sections alone were recorded in Abby Road), it's what the album pioneered that places it on this list. In 1998 a tidal wave of Dutch laser-kissed trance, pre-donk hoover-bassed hard house and the Champagne-breathed swagger of late-90s speed garage were washing through clubs, bars, airwaves and holiday resorts. It was an overwhelming period of extremes and excess; vodka Red Bull was outselling lager, DJs were becoming mega-rich superstars and Mitsubishi pills were making clubland intensely emotional. Cutting through the haze of debauchery and waiting for you at the end of the weekend, like a soft duvet and mug of hot chocolate, was Air's ‘Moon Safari’.

The album defined the calm after the strobe-storm; 'Chill' – or 'Chill Out' as it had somewhat cringingly been tagged – became the adopted after-genre by clubbers of the day. ‘Moon Safari’ set the template for this electronically soothing sound of Sundays that would pave the way for Groove Armada, Royksopp, Lemon Jelly, Silicone Soul, Zero 7 and Sia. Revisited today ‘Moon Safari’ is still the perfect album; 'All I Need' is the sonic equivalent of a shoulder massage in a warm bath of White Russian, 'La femme 'D'argent' and ‘Talisman' float through you like old memories filled with intrigue and whimsy, while the more upbeat tracks (by which we're only talking sub 118 BPM) like 'Sexy Boy', ' Kelly Watch The Stars' or The Beach Boy's sampling 'Remember' give the album enough uplift without demanding you jump all the way back into your rave-sodden trainers. Well, not until next weekend any way. Nick Stevenson

Drexciya 'Neptune’s Lair' (1999)

It’s quite hard to fully summarise the impact that Drexciya have had on electronic music without writing a gushing love letter to Detroit’s finest duo. Electro is electro because of the vast works of staggered, frenetic art that James Stinson and Gerald Donald created. After years and years of sub-zero EPs and club-astonishing tracks, ‘Neptune’s Lair’ arrived via Tresor in 1999 and acted as an amalgamation of the sounds that they’d been creating and tinkering with since the late 80s. It’s a rich, expansive body of work: take the sprawling, hypnotic and almost 8-bit ‘Organic Hydropoly Spores’ for instance.

It’s basically a down-tempo love ballad for robots that soothes and subdues, but think of it also as a slow jam that’s preparing you for the pummelling, pounding ‘Devil Ray Cove’. This little ripper comes in at 2.51 but packs more venom that 90 per cent of the “hard” dance music released today. That’s the point though: Drexciya set the bar so high with their output and this album especially that all other imitations just never hit the spot. Stinson’s untimely passing in 2002 is still hard pill to swallow, especially when electro’s sound and also recent surge in popularity is largely down to his work. Electro is electro because of Drexciya and ‘Neptune’s Lair’ proves it. Funster

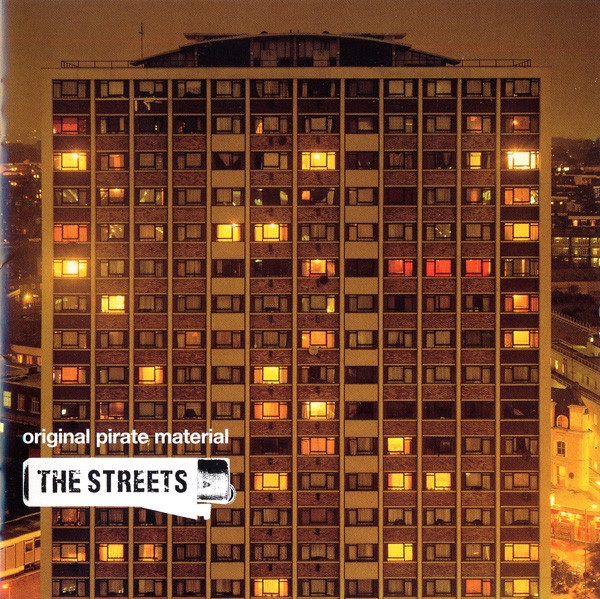

The Streets ‘Original Pirate Material’ (2002)

By the time the unmistakable piano loop of ‘Has it Comes to This’ started picking up daytime play on Radio 1 in 2002, dance music wasn’t in a great place. UK garage – which Skinner ploughed so furtively for much of his debut – had reached its commercial zenith the previous year and the super club bubble of the late 90s had well and truly burst. To a new generation of teens, the sounds of stripped-back garage rock emanating out of New York started to seem more appealing than the latest house or garage record. But with his tales of first time Es, kebab shop fights and neglected loves, Mike Skinner managed to build a bridge between two generations of British ravers. For those coming to the end of their party years after the celebratory 90s, it was a nostalgia-tinged, yet unflinching look back on all they’d been through.

For those in their early teens, it was a road map for all that was to come. Skinner’s genius on ‘Original Pirate Material’ was to use things we were already familiar with to create something brand new. UK garage, ska and hip hop were all put through the blender alongside stories of characters we had all met and nights out we had all had… or were certainly going to have. Its influence was almost immediate with a slew of poor sound-a-likes including Just Jack and Hard-Fi retreading Skinner’s everyman tales, while Skinner himself was instrumental in bringing through UK talent like Kano and Professor Green. But 16 years on, the true size of its influence keeps growing, with everyone from Kojey Radical to Jamie xx singling it out as one of the most important British albums of a generation. Sean Griffiths

Dizzee Rascal 'Boy In Da Corner' (2003)

Before Dizzee Rascal introduced himself looking menacing in that bright yellow corner, the word 'grime' to the mainstream consciousness would have just been something seen on bottles of kitchen cleaning products. Even after he won the 2003 Mercury Prize there was no name-check for the genre in the Guardian's article announcing his accolade. But anyone who'd grown up listening to pirate radio in the time UK garage was transitioning into a darker sound would've known exactly what Dizzee's coming together of chaotic kicks, harrowing melodies and tales of LDN life was. "My name is Raskit, listen to my slang," Dizzee directs us on 'Cut 'Em Off'. He knew his Urban Dictionary-friendly colloquialisms would be alien to many listening and that's what made it so exciting. Nothing like this had been heard before on a widespread scale, from the grim lyrical clattering of 'I Luv U' to the slap-to-the-face beats of 'Stop Dat'.

He was flying the flag for the UK's underprivileged, showing kids just like him what could be achieved even with pot-shot lyrics like "I'm a problem for Anthony Blair" ('Hold Ya Mouf') and "we chuck grenades at Scotland Yard" ('Seems 2 Be').Of course artists like Wiley and 'Pulse X' producer Youngstar deserve credit for grime's earliest productions, but without 'Boy In Da Corner' the genre might not have tasted the success it has in the last few years. "I've influenced a whole sound," Dizzee told Red Bull in 2016. He ain't wrong. Stormzy's 2015 hit 'Know Me From' samples 'I Luv U' and Skepta's 'Man (Gang)' pinches the 'Cut Em Off' lyric "I only socialise with the crew and the gang". Taking into account the star status of those two artists, Dizzee Rascal deserves some thanks for an album being mentioned in tracks for over 10 years. Dave Turner

Ricardo Villalobos 'Alcachofa' (2003)

Like many budding genres, the more minimal forms of house and techno seemed to remain in the shadows for much of its early evolution during the mid to late 90s. That said, once the new millenium hit, awareness grew immensely due to a string of talented producers that allowed the music to reach more ears. A major leader in this big push was Ricardo Villalobos, the unique Chilean talent who has since become the posterboy for all things stripped-back and minimal. Yet back in 2003 his genius was only just beginning to garner attention.

His debut album ‘Alcachofa’ was a major factor in establishing the widespread appeal, with delicate and trippy textures layered over steady and fine rhythms to create masterful productions that keep the listener surprisingly engaged. Tracks like 'Easy Lee', 'Dexter', 'Theogenese' and the rest of the nine track collection offer a mesmerising display of sonic exploration that is undoubtedly distinctly Villalobos and helped cement his place as one of the most creative producers in recent memory. Plus, the material transcended just his own fame and inspired a wave of new producers to test their skills at the subtle brilliance of minimal electronic music. Harrison Williams

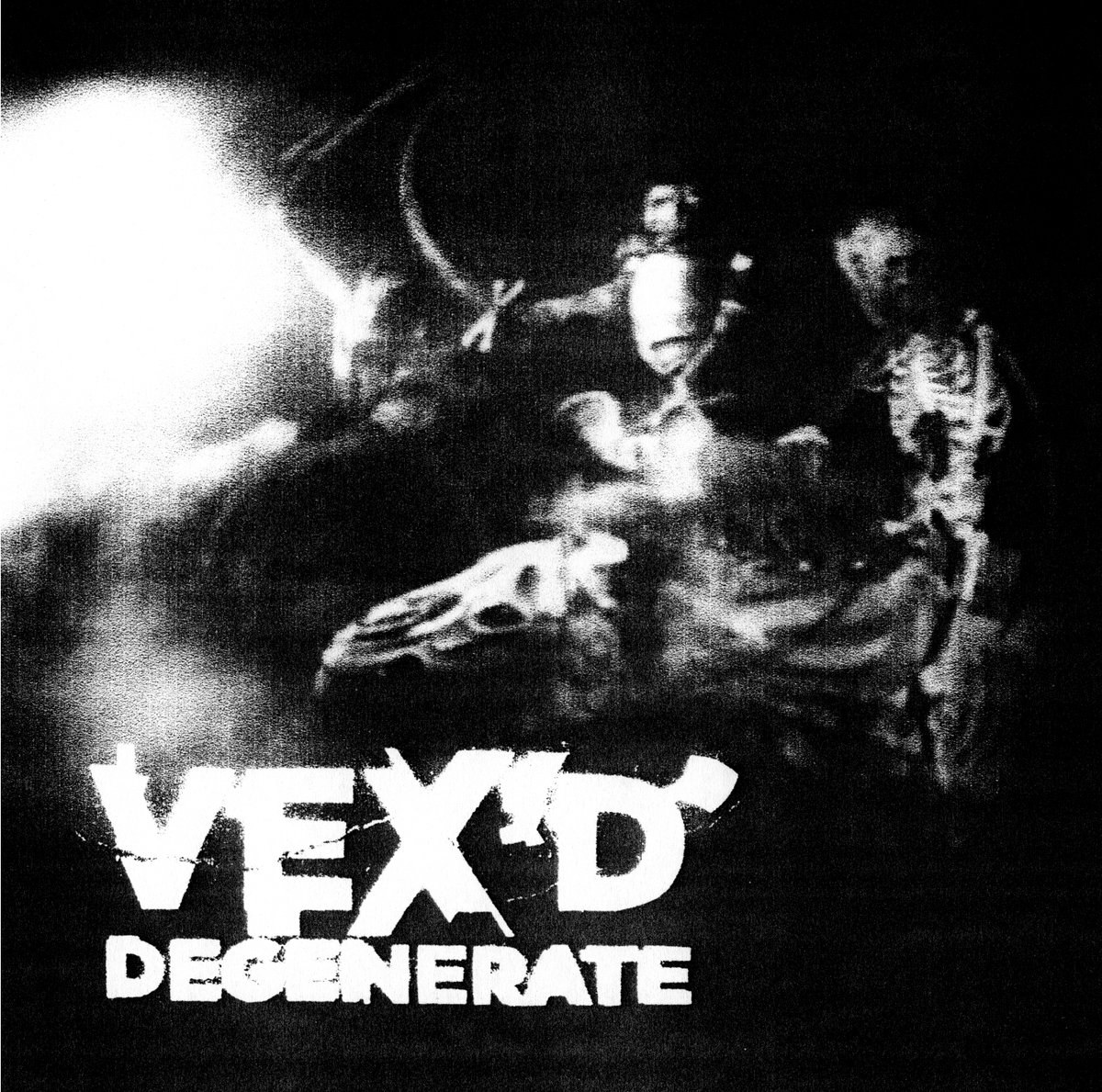

Vex’d 'Degenerate' (2005)

When this album emerged in 2005, we still didn't know – as Wiley put it – “wot u call it”. “Dubstep” had been invented, was brewing as a still-minuscule scene, and Bristol based duo Jamie Teasdale and Roly Porter aka Vex'd were certainly connected to it, but some were saying this was “breakstep” thanks to its rolling junglist feel, others calling it “grimey”, which its juddering claps could be seen as, even though it didn't have rappers. It was all very confusing. But it was also thrilling: every track burned with furious rave energy, but held back, condensed into almost unbearable tension, very rarely allowed to cut fully loose, as layer upon layer of roaring bass and stuttering beats were added.

These tracks still sound simply immense, and it's likely they pushed the likes of Coki, Skream and Rusko to amp up their bass wobble and send dubstep into stadium territory a couple of years later. But Jamie and Roly could do subtlety too, and just as their respective solo work would voyage into cinematic territories, Vex'd influence can be heard on every bit of dark electronica in today's world: from Chino Amobi to Arca, Death Grips to most of the Houndstooth stable, Vex'd's vicious pressure still reverberates. Joe Muggs

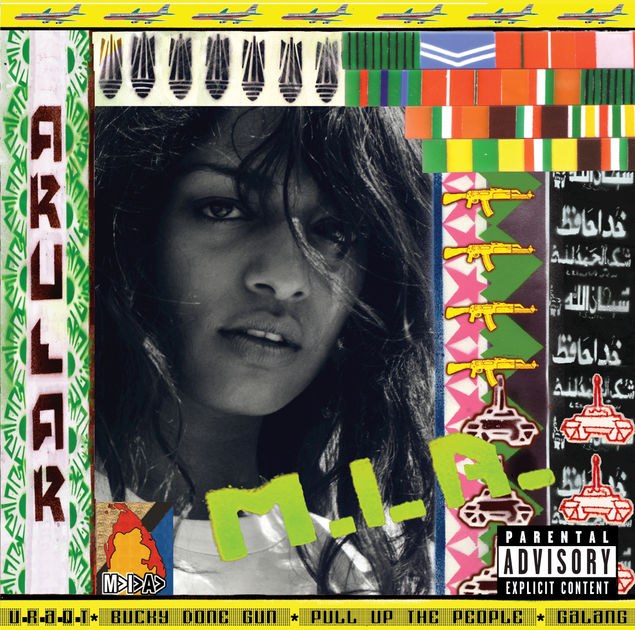

MIA ‘Arular’ (2005)

The odds are Diplo would never be the mammoth force in dance music he is today without ‘Arular’. The EDM titan was the mastermind behind MIA’s ‘Piracy Funds Terrorism Vol. 1’ mash-up mixtape that helped create a buzz around the Sri Lankan singer’s forthcoming debut. But Diplo’s influence is still minimal to the impact MIA has made with ‘Arular’. The Londoner’s debut is an eclectic masterpiece of various underground styles. It condenses a blend of US hip hop, grime, electronica, baile funk, dancehall, and so forth, into concise 4-minute pop songs, and gets as close to ‘world music’ as we’ve ever come.

Tracks like ‘Galang’ and ‘Sunshowers’ showcased how less conventional, non-Western sounds could find audiences – something we’ve seen with increasing frequency in recent years with the likes of J Hus, the Mixpak crew and Diplo himself. It can’t be understated that M.I.A. also helped pave the way for unconventional women of colour on the scene – opening the door for acts like Santigold, Azealia Banks and FKA Twigs, to name but a few. On ‘Arular’, M.I.A was nasty, she was sweet and, most importantly, she wasn’t about to play into the hands of expectation. Charlie Case

LCD Soundsystem 'LCD Soundsystem' (2005)

In the early 2000s New York was the place to be. Just not for dance music. Indie bands like The Strokes and The Yeah Yeah Yeahs made the city cool for music hipsters again. But with such a strong history of dance before it, from the Studio 54 to the Paradise Garage to the club kids, it was inevitable these influences would filter in, and like the Talking Heads and Blondie before them, bands like LCD Soundsystem and The Rapture kick started a dance-punk movement for a new generation.

With label DFA the hub for this new, ferocious and unhinged take on dance music, LCD Soundsystem took centre stage with their self-titled debut album. The album literally kicks off in debt to dance with ‘Daft Punk Is Playing At My House’, a guitar driven tune with the punchy, DFA-signature drums worthy of any club soundsystem. Then there’s the campy synth line of ‘Tribulations’, the disco glitz of ‘On Repeat’ and the manic percussion of ‘Thrills’, all coming together to inject a much-needed dose of attitude into NYC’s then flagging dance music scene. What followed was the likes of Errol Alkan, Trash, Justice, The Klaxons and the blog house movement, artists and nights inspired not by the po-facededness of techno and house or the cheesiness of trance, but the carefree attitudes and character-driven music of LCD Soundsystem’s tongue-in-cheek vision of disco. Louis Anderson-Rich

Skream 'Skream!' (2006)

Given the rapidity of hype cycles and the instant availability of music online, it’s now hard to imagine the blossoming of a genre of music that your friends have literally never heard of. SoundCloud uploads are tagged; producers take to Twitter to refute the labels given to them by fans or journalists; scenes are defined and dissected while still in their embryonic stages. But when Skream’s landmark debut album dropped in 2006, people were genuinely asking “What the fuck is dubstep?” and wondering where this strange new sound was coming from. Dubstep is probably the last major genre to have taken electronic music by surprise in such a way; it was nurtured on pitch black dancefloors by those in the know before a rapid explosion in popularity, catching so many off guard. While there are other seminal dubstep albums – Pinch’s ‘Underwater Dancehall’ in ‘07 and Benga’s ‘Diary Of An Afro Warrior’ in ‘08 – ‘Skream!’ was the one that lit the touch paper.

It’s packed with heat: the seminal ‘Midnight Request Line’, proper naughty dub workouts ‘Blue Eyez’ and ‘Stagger’, gun finger anthems ‘Rutten’ and ‘Check-It’ (with Warrior Queen) and the contemplative, blissed-out ‘Dutch Flowers’ and ‘Summer Dreams’. The full spectrum of the genre is represented, with sublime production from one of dubstep’s OG instigators. So what happened next? The sweaty, aggravated-looking young man from the album’s cover – standing, awkwardly, just out of the action at a house party, a neat visual status for dubstep’s outsider status at the time – went on to stratospheric success, taking dubstep with him until it blew out of all recognisable proportion. World tours, ridiculous stage design, stadiums full of people gagging for the drop – Skream experienced it all. And this LP will forever be an insight into what it was like when it was just a well-kept secret. Seb Wheeler

Burial 'Untrue' (2007)

Like many self-confessed Burial romantics out there, it’s safe to say each of Will Bevan’s records resonates just a little bit differently from the next. But for myself, and a whole sea of like-minded listeners eagerly drinking in the sounds of the mysterious man with the weight of the world on his shoulders, it was ‘Untrue’ that ignited a spark of artist/admirer appreciation not found in previous Burial offerings, or indeed other more mainstream dance music works that came out at the time.

Landing in ’07 on Kode9’s ever-evolving Hyperdub imprint, the power of the project lies firmly within its disturbing relatability. Then and now, the dystopian dream world conjured up on ‘Untrue’, the crackling connotations or indeed the murky underground metropolis he envisioned throughout the album (and his entire discography), showcased the importance and the pleasure of introversion in dance music. I’ve witnessed adults weep and smile in equal measures in club spaces having heard just a few seconds of an ‘Untrue’ track, watching on as waves of nostalgia and emotions connect dancers through a shared experience with Burial’s music.

But to have a sound so signature to time, place and self is a great feat indeed, and one that should be celebrated sincerely in the decade since the release of ‘Untrue’. When it comes to Burial, and indeed this intimate body of work, the merging of 2-step, dubstep, ambient, jungle and a clear affinity for female r‘n’b inflected vocals set the bar for a whole generation of ‘post-’ era artists, including the likes of Mount Kimbie and James Blake, who felt at home with the dissociative, comedown transcendence oozing from the album.

Today, the legacy of ‘Untrue’ remains as bold and brilliant as ever. Described by Mary Anne Hobbs last year as, “Avant-garde, timeless”, ‘Untrue’ is a classic piece of dance music history. Jasmine Kent-Smith

Justice '†' (Cross) (2007)

It’s 2007 and the kids want techno but not the sound of Jeff Mills, Robert Hood and the Detroit slam that’s been synonymous with dance music since the late 80s – oh no, they’re after something different. As a mutant crossover of electroclash and indie began to rock its way round dancefloors because of DJs like Boys Noize and Erol Alkan, a French duo burst into the world like a pair of mischievous banshees, intent on causing one hell of a ruckus in the rave. If Daft Punk are anything to go by, then it’s evident that clubland has always shown a fondness towards Parisian pairs and Justice became Guy Manuel and Thomas Bangalter for the millenial generation. ‘Cross’ was the album that didn’t just define dance music when it was released, it introduced people to it.

Gnarly, frantic, anarchic electronica that went all in on samples and all out on carnage; It’s one of those albums that gives you the chills when you listen back because every song holds a specific memory, it represents an era of independence. 17-year-old me will never forget hearing ‘Genesis’ for the first time – those chords, the majesty, that icy starkness. It triggered something inside me that hasn’t been the same since. The video for ‘Stress’ is a now legendary piece of work that shows a bunch of trouble-making teens riot around a city bearing cross logos on their jackets, cross logos that are now instantly recognisable to anyone with even a passing interest in dance music. ‘D.A.N.C.E’, ‘Phantom Pt 2’, ‘Valentine’ ‘Waters of Nazareth’; you know the score, absolute bombshells, the perfect mix of unashamedly fun and intrinsically French. Over a decade and two more albums later, Justice are still one of the world’s most sought-after acts but when all is said and done, ‘Cross’ not only changed the game for them, it changed it for all of us. Funster

Giggs 'Walk In Da Park' (2008)

UK gangsta rap – or road rap, as it’s become more widely known – initially started in the pre-gentrified streets of Brixton, South London, by a crew called P.D.C at the top of the millennium. Headed up by JaJa Soze, their stylings were heavily inspired by the hood realities of NYC in the late ‘90s, and would later birth a grime crew by the name of Roadside G’s. Fast forward to 2007, and the whole game got flipped on its head a 10-minute bus ride away, over in Peckham, by a rapper we now know as The Landlord, Giggs, whose 2007-released single, ‘Talking Da Hardest’, was a defining moment in British music: here we got an authentic look into how real street life was for many young people across the UK. Where grime music thrived in the dance, road rap really did live on the roads, in tinted cars and in barber shops.

Following ‘Talking Da Hardest’, in 2008, Giggs released his debut studio album, ‘Walk In Da Park’, and I remember it clearly: being in the ends and it replacing everyone’s love of US rap, for two years straight: namely anything released by 50 Cent, whose ‘Get Rich Or Die Tryin’ LP had literally run our roads since its 2003 debut. ‘Walk…’ was our version of that album, the hard-hitting productions allowing Giggs’ monotone flow to become the legend that it is today. From the bando-inspired bars of ‘Cut Up Bag’ to Mother’s Day anthem ‘You Raised Me’, Giggs showed early on how versatile he was as a lyricist, and indeed how important a genre UK rap would go on to be. Joseph JP Patterson

James Blake ‘James Blake’ (2011)

It seemed as though dubstep had been completely hijacked by the wobbly, face-melting basslines of producers like Skrillex and Borgore in 2010. The dark, intricate subtleties it replaced, however, were finding new life in the underwhelmingly labelled ‘post-dubstep’. James Blake served up three stylistically different EPs that year (‘The Bells Sketch’, ‘CMYK’ and ‘Klavierwerke’), each increasingly exploring a slower, quieter chasm of electronica. But it would take the release of his self-titled debut in 2011 to make a caustic change to the dance music landscape. To understand how James Blake’s self-titled debut made such an impact, look no further than its Feist-covering, lead single.

On ‘Limit To Your Love’, James strips the folksy love ballad down to raw piano and vocals, adding a car shaking, single-note sub-bass. And with it, he made muted music the new normal. Like an electronic sleeper cell, the record would sneak into bedrooms and radio playlists with its Bon Iver-esque, lovelorn lyrics, but dismantle speakers with glitchy vocals, throat-throbbing basslines and 2-step rhythms. Simple? Yes. But it’s an influence that could not be contained. Where the airwaves were once full of raging wobbles, they were soon filled with the brooding r’n’b-tinged electronica of artists like Jamie Woon, FKA Twigs and SBTRKT. James Blake said it best himself an interview with the Guardian in 2016: “I’ve subdued a generation. That will be my legacy.” Charlie Case

Rustie 'Glass Swords' (2011)

‘Glass Swords’ epitomised the “anything goes” approach to bass-heavy dance music that manifested at the turn of the decade. It was a glorious landscape, one in which records like Ikonika’s ‘Contact, Love, Want, Have’, Kingdom’s ‘Dreama’ and Untold’s ‘Anaconda’ sprouted like colourful, dizzyingly exciting flowers. The shock of the new could be felt on every dancefloor, as dubstep imploded and a new rush of low-end energy and experimentation surged forth. This was no truer than in Glasgow, where Hudson Mohawke was busy redefining hip hop production and labels like LuckyMe, Numbers, Dress 2 Sweat and Wireblock were pressing backflipped bangers at a rate of knots (Jacques Greene, Bok Bok, L-Vis 1990, Deadboy, Machinedrum, Mosca and Mike Slott all launched from this bevy of imprints).

Then there was Rustie, hyperactively fusing together trance, happy hardcore, prog rock, video game sound FX, Timbaland’s swagger and Flying Lotus’ wobbly psychedelia. He signed to Warp in 2010 and released the best album of this fertile period a year later. An absolute joyride, the juggernaut drops and rollercoaster synths of ‘Glass Swords’ set the template for future movements like PC Music, Fractal Fantasy and similar-minded bass cadets Iglooghost and Slugabed, even setting a prototype for the brash, Big Room EDM that began marching through North America shortly after. And, seven years later, it passes the ultimate litmus test – sounding as future-proof now as it did back when it first landed. Seb Wheeler

Jam City 'Classical Curves' (2012)

Seven months after Rustie’s ‘Glass Swords’ pushed music to serotonin-dripping maximalist extremes, Jam City found the sublime in minimalism. Before ‘Classical Curves’, sundry styles of international club music were gaining popularity beyond their own scenes and being played next to each other at parties such as Wildness in LA, GHE20G0THIK in New York and Nights Slugs in London, but no producer synthesised the bare-bones elements of everything from Jersey club and Detroit techno to jazz fusion and grime until Jam City’s debut LP dropped.

Stripping isolated influences into next-level concoctions, and fronted with glossy artwork displaying a motorbike lying flat on the floor of an expensive property, ‘Classical Curves’ built up a glistening, aesthetically rich world with dancefloor impact lurking within its uncanny atmospheres. “It's interesting, I can play a whole set of tracks that basically rip off two or three key tracks on ‘Classical Curves’,” said Night Slugs co-founder Bok Bok in an interview with The Quietus two years on from the release of Jam City’s pioneering work. There wasn’t a hint of hyperbole in his comment. The engrave of Jam City’s stylistic direction has been conspicuous throughout the wave of ‘deconstructed’ club music that has followed. Patrick Hinton

Disclosure 'Settle' (2013)

January 13, 2012: Disclosure play Corsica Studios in London. It’s one of those nights in Room 1, where hype fills the air and too many bodies manage to fill the small, black dancefloor. The brothers from Surrey are the sound of right now and, as everyone here suspects correctly, the not-so-distant future too. They’ll go from this stage – still driving themselves to gigs and perching their instruments atop oil drums at less well-equipped venues – to releasing a number one album in ‘Settle’ and a set at Coachella before 2013 is out.

Like all the thunderbolts that send shockwaves through our scene and out into the real world, their phenomena is twofold: Guy and Howard, just 22 and 19 when ‘Settle’ drops in the summer of 2013, introduced a legion of teenagers to the sugar rush of house and garage and, in turn, to the joys of raving and high quality ecstacy. The UK underground fell in love with the homegrown, new-skool house that Disclosure epitomised and fresh-faced kids the country over realised that dance music is The One. The sound was everywhere, unstoppable. This power surge then lit up wider pop culture as four singles from ‘Settle’ landed near the top of the UK singles chart, paving the way for number ones from Duke Dumont, Breach, Ben Pearce and the rebooted Storm Queen in the months after the album’s release. A nationwide serotonin rush occurs.

Heads will side-eye the classic house and garage motifs on ‘Settle’ but the album represents the peak of the UK house explosion that started with ‘Battle For Middle You’ in 2011 and ended with ‘House Every Weekend’ in 2015. It’s Larry, Kerri and Todd viewed through a resolutely UK lens, tooled up with womping basslines, hooks that’d make Craig David or Elisabeth Troy weep with happiness and slick production ripe for strobe-lit main rooms. Its influence remains, to be found in UK bass house and setting the blueprint for pop house by the likes of Gorgon City.While you won’t hear much from ‘Settle’ dropped these days (house remains, but fashion, hype and subgenres swiftly change, and it really was The Sound Of That Summer), the music still stands up, the reflection of a very sunny time for dance music in the UK. In at #2, ‘White Noise’ was a genuinely subversive crossover hit and although such credibility has all but disappeared from the singles chart, the energy that ‘Settle’ sparked definitely hasn’t. It was a gateway, Guy and Howard the pied pipers who led many toward the light. Seb Wheeler

DJ Rashad ‘Double Cup’ (2013)

Although it’s been bubbling since the mid 00s and has a lineage that throws back through juke and ghetto house, the Chicago sound of footwork “broke” in 2010 when Planet Mu dropped the ‘Bangs & Works’ compilation, introducing 160bpm freneticism to an audience outside of the Windy City’s dance battles and smoked-out home studios. Dancer-turned-producer DJ Rashad scored two tracks on that comp, igniting a career that would see the Teklife co-founder represent footwork around the world and be responsible for the genre’s most inventive and critically-acclaimed output.

‘Double Cup’ is Rashad’s masterpiece. It arrived at the height of his power, when he’d established a global network of footworkers and Teklife devotees thanks to relentless touring and a ‘no borders’ attitude to spreading the sound. The album itself moved footwork away from its roughshod roots, presenting 14 finely-crafted tracks that saw the Teklife camp level up to a plump, slick but no less incendiary production style.

Crew members Spinn, Taso, Earl, Phil, Manny and Addison Groove all contributed, showcasing Rashad’s love for collaboration and belief in moving as a team in order to progress and prosper. Their work demonstrates perfectly footwork’s propensity for absorbing influences – acid, rap, r’n’b, jungle, classic house, noise – and its perpetual search for The Future. The album was so powerful that it set a benchmark for all footwork to follow and, having sent shockwaves through the underground, saw Rashad’s influence creep mainstream. ‘Double Cup’ led to him touring with Chance The Rapper and remixing Snoop Dogg but, heartbreakingly, he passed away just 6 months after the record’s release, cruelly halting an ascent that could have changed the very fabric of pop music (imagine Rihanna on a Rashad beat). File ‘Double Cup’ under Cult Classic, one that remains the high-watermark of an entire genre. Seb Wheeler

Arca ‘Arca’ (2017)

Quite often, the most memorable and acclaimed artists in the world are the most singular entities. Attitudes, personalities and characteristics that are completely unique to one person set them aside from the over-saturated crowd. Thom Yorke, Anohni, Seth Troxler and Bjork. A pretty eclectic bunch, right? All have their own style that is almost completely inimitable and that’s what’s made them who they are. Arca probably falls more in this category than anyone else and has been sculpting a beautifully-jagged and urgent sound for the last five years. Arca's aesthetic, both in appearance during live shows and visuals displayed during them, portrays themes that don’t shy away from taboo or shock, in fact, they gravitate towards it, often depicting highly sexualised, graphic imagery (when ‘Whip’ is played during his live show there’s footage of someone being aggressively fisted). Of all of Arca's albums, the 2017, self-titled ‘Arca’ album is most passionate, endearing and stark. It’s hard to imagine those three words used to describe one body of work but then again it’s hard to describe Arca. Tracks like ‘Anoche’ and ‘Desafio’ are highlights but as a complete body of work, it’s undeniably hard-hitting.