Features

Features

Sarz Is Protecting His Inner Child At All Costs

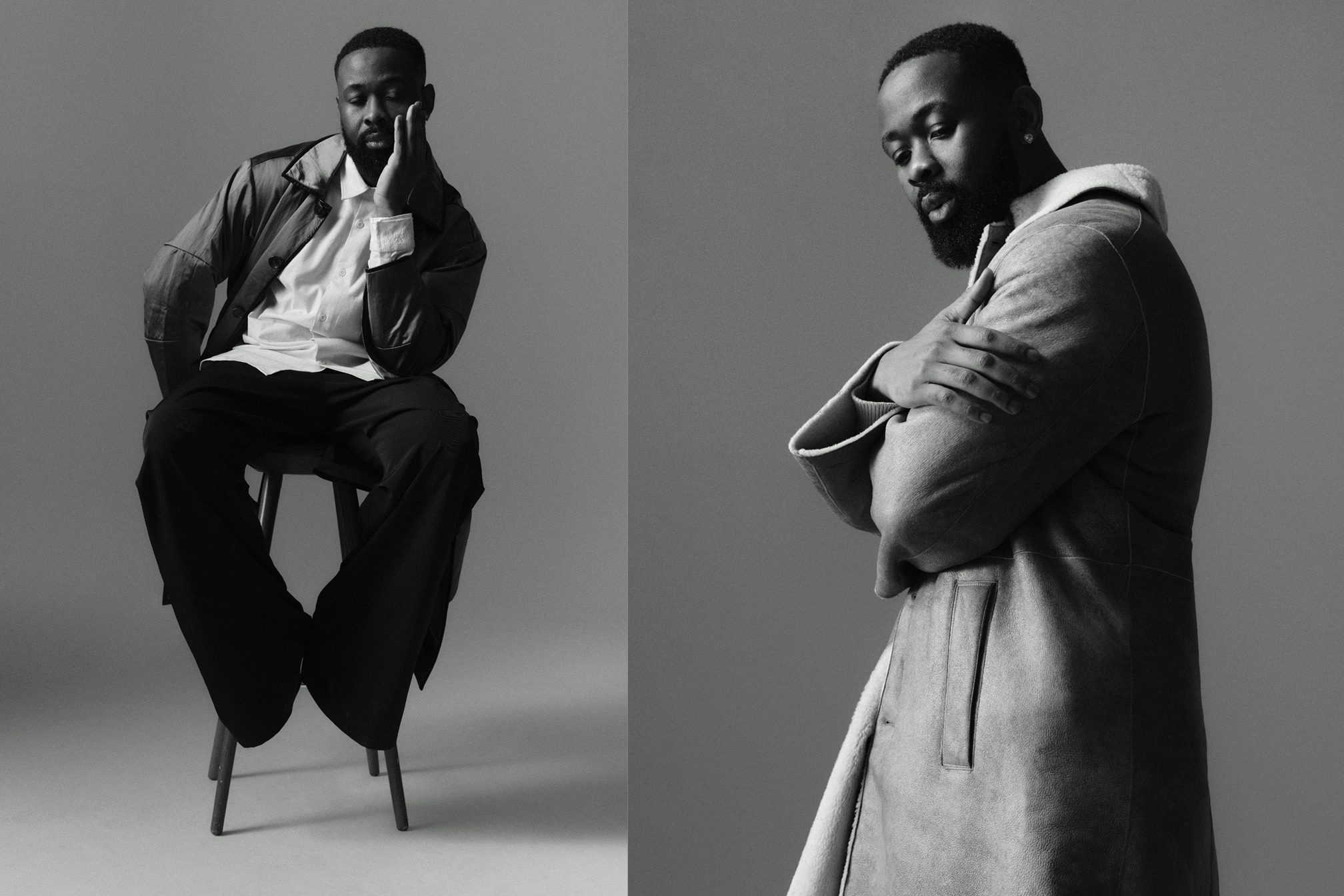

Nigerian super-producer and DJ Sarz grew up in a household that demanded academic success and dismissed artistic pursuits. Now an international icon, he's building a new legacy for himself and uplifting young artistic peers to overcome Western musical hegemony. He speaks to Nicolas-Tyrell Scott about his journey, motivations and forthcoming debut album

Behind the veil of celebrity, all that Osabuohien Osaretin wants to do is find the time to catch Deadpool & Wolverine in a movie theatre. As the peach hues of a late-summer’s sunset beam into the Shoreditch office of Metallic Inc, his management company, the seismic-super-producer known to the world as Sarz morphs into his three-year-old state, feverish at the thought of spending a spell of free-time marvelling at the latest comic book movie adaptation. “I need to make sure I catch it,” he enthuses. “That’s what I’ll go outside to do.”

Sarz is currently in London, and generally found between the UK, New York (and wider America), and Nigeria, doused in the pressure to submit his latest album on time — his deadline moving further and further into the abyss, as new ideas surface, or clearances need attending to. His co-manager Tia later corroborates this: “With Sarz, things are always, always moving, his mind is always on the go.” Like the upcoming LP’s title, the star has briefly adopted a ‘Protect Sarz At All Costs’ mantra, leaving the house only for important duties, like our interview.

Broadly, Sarz is not opposed to leaving his home — he’ll venture out with friends, engage in leisurely activities, or a dinner here or there — but ultimately, its lucid pleasures, such as dwelling in bed for longer periods than his alarm that he fights for. “The ratio of going out to staying indoors has changed as I’ve grown up,” the 35-year-old says, his tone oscillating between firmness and pacification; he’s a man that’s assured of what he wants, but not imposing with his life choices. As an infant, he’d spend his time submerged across stratified universes. Among video games, he discovered what would become his gateway comic book series, X-Men, in awe of the narrative arcs and characteristics sculpted across each and every page.

“If we’re talking X-Men specifically, then it has to be Wolverine,” Sarz asserts, when asked his favourite character. His captivation stems from the human components that drive the extra-terrestrial traits of each hero or villain. “Deeper origins move me, what makes the person who they are, and there’s depth to the human Logan.” He’s drawn to the same qualities in alien characters: Superman, who hides behind everyman identity Clark Kent, is his favourite DC hero, while his favourite contemporary comic book adaptation is Avengers: Endgame, particularly moved by Thanos’ methodism and how he tackled each person’s weakness. “It’s real, you can see this play out in the actual world,” he says. “I know he’s a villain, but he thought about things, he had a strategy.” Sarz’s pace is slower than usual here, the intention behind his sentiments colouring the room.

Raised in Lagos states’ north-eastern city, Ikorodu, the Nigerian prodigy focused his mind on everything that he was passionate about. In the tangible world, beyond the four walls of his bedroom, he’d attentively watch basketball outside a local court close to home. Observing amatuer players in their twenties, he grew fixated with the game, also studying the sport at home via the NBA. The technique of a Steve Nash and the wider camaraderie of the Phoenix Suns at the time enamoured a 13-year-old Sarz and in senior secondary school (SS1), and he’d spend his free time at the court, eventually finding the confidence to challenge the figures 10 years his senior that he’d studied. “My cousin used to play with the older guys,” he said. “He’d teach me once they’d leave the court everyday.” Soon, he went from a “reserve” pick to being selected outright, despite his age, gaining the confidence to show off with his dribbles, shooting and scoring frequently. “‘We have to have this guy on our team’,” he recalls his peers saying, leaning forwards as he continues. “It gave me some of my first memories of confidence and people who saw me.”

A self-proclaimed self-learner, Sarz could apply himself independently to anything that caught his eye. It’s one of the traits that allowed him to complete his school-work with ease, often seizing top grades. However, paternal dynamics within the household were not always saccharine, with his father often clinging to archaic perceptions of success. Coming first (out of their whole class across assignments and tests) was the only redeeming position for Sarz and his older brother growing up. “I’d be constantly getting third position, that’s good?” he begins, his inner child presenting himself once more across his rhetorical question. Nodding in response to him, he takes my cue to continue, his utterances sombre as he does so. “That’s not good enough for him, he used to beat me because of that.” A contributing factor to Sarz’s intrinsic ethos of self-application, was also a competitive streak. It’s what led to the accumulation of more than 400 CDs — part inherited, part self-purchased — the most amongst friends.

Read this next: 10 years of Mavin Records: How the Nigerian label helped take Afrobeats global

Sarz’s ascent, which now sees him perched atop a list of Nigeria’s, and West Africa’s, most sought-after producers — a legacy that’s seen his skills touch a pantheon of talent from Tems to Rema to Burna Boy to the Starboy himself in Wizkid — began innocently, in his brother’s archives. Like a lot of African countries, as well across the Caribbean, American cultural production held a sphere of influence across nations within these regions; from the charisma displayed from Busta Rhymes, Michael Jackson, or Madonna across MTV, to Nickelodeon’s growing might in infants, the late ‘80s and ‘90s were coloured with North American inflections, alongside pre-existing domestic and geographical cultures. For Sarz, this meant his early musical ear developed with a fixation on ‘90s and early ‘00s hip hop and R&B.

“My brother and friends were constantly in competition, we had to have the best collections, naturally I joined in,” he says. 50 Cent’s ‘Get Rich or Die Tryin’’, Kanye West’s ‘Graduation’ and Obie Trice’s ‘Cheers’ were prominent projects, etching themselves across Sarz’s adolescence and early adulthood. “I like albums based on their production alone,” he reveals. “The words are not something that I pay attention to as much.” This methodology has followed Sarz to present-day, his curation in the studio is the pillar that matters most to him — sonics, what the sounds crafted are saying, and how they make himself and others feel matter more than lyricism. His eye first darted towards production through a mutual friend of his brother’s. “James was producing for a group called The Soldiers at the time,” Sarz laughs, almost embarrassed to repeat the name, anticipating judgement.

He was in awe of the recording process and the computer equipment and software used to create the foundation of the group's songs. “He showed me Fruity Loops, it was on three at the time. For context, it’s now at 21, that’s how old I am.” Chuckling, he remembers being given a demo version of the software by James. Exporting every production he crafted that he was proud of, he would send to the group, as well as local group J Lords. Validation came when the group liked two of Sarz’s four presented to them. “‘I must be doing something great then’ I thought, I got paid for that as well.” Becoming cognisant of being remunerated for producing, he saw the work as a means of financial liberation from his parents. “I don’t need to ask them for money anymore,” he says. “I can get myself those clothes, or what I want to eat, that’s where my love of music production begins.” On a gap year at time, having failed an entrance exam to study computer science at the University of Lagos, Sarz continued to produce, solidifying his ear from behind the booth.

Culturally, Sarz was still entranced by American hip hop at this time. At the apex of his early references was Timbaland. “I remember trying to create ‘Bounce’, it was so bad thinking back on it, but I loved his beats,” he remembers. Calling other pivotal 2000s’ voices like The Neptunes, Pharrell Williams independently and Bangladesh, Sarz idolised the golden eras that came with the early-to-mid-noughties dominance of both hip hop and R&B. From southern staples like Ludacris, Bobby Valentino and Ciara to Mary J Blige, Jay-Z and 50 Cent, luxury and audacity entered the fore in both genres’ aesthetic and lyrical content. Songs like ‘What More Can I Say’ documented Jay-Z’s determination and ascension as a Brooklyn landlord, his rings a material signifier of his arrival. Moments like this emphasise the gravitas of this point in time, and why it influenced many outside nation and state lines.

Read this next: Impact and inspire: The anatomy of Wizkid's rise to Afropop stardom

It was only in the latter half of the decade that Sarz found fragments of his ethnic origin atop the basslines. After his work with J Lords, he found himself while working alongside 9ice and Jahbless — the latter of which earned him his first bonafide breakthrough with a remix of ‘Joor Oh’ —both of whom often spoke in Yoruba and fused genres like fújì with rap. “They barely spoke in English when we’d work,” Sarz recalls. Being coerced into learning Yoruba through being made fun of for its absence in his life, he learned on-the-job, circumventing the jestful shame (“I’m not the best speaker, but I understand everything that’s being said now,” he clarifies). Eventually, language and the culture to which Yoruba exists within nudged Sarz to explore a palette his father imbued on him when punishing him as a child.

“Whenever my brother and I were having too much fun, my father would force us to sit and watch the news, with an array of older school Nigerian artists playing in the background,” Sarz shares. The super-producer hated the experience at the time, as it often took away from the video games he’d play with his brother. But, in his mid-twenties, the names, songs and references finally proved useful in Sarz’s formative years as a new-age producer. Among conventional titans, like Fela Kuti and King Sunny Adé, sat Ebenezer Obey, who his dad would play as early as 5:AM in the morning. “It would always, always wake me up, I used to hate it actually,” Sarz recalls. His teeth make a rare appearance during our interview, the memory causing him to both laugh and cringe simultaneously. It lightens the dullness in the sky that paints itself outside our four walls, Shoreditch quickly submerged in the evening's darkness.

Today, Sarz’s offerings serve as an ancestral crescendo, paving paths forward just as much they lean inward towards his roots — his productions a triumph of lineage. Drums, a Sarzean signature, have come to add dimension to personality, urging songs forward and nodding to their emotional sentiment. On the WurlD-assisted ‘EGO’, they add a rural and pure urgency, pushing the listener to sympathise with WurlD’s battle with his discontentment with a lover, whereas they skate across the Wizkid and Skepta collaboration ‘Longtime’ courting the listener into submission. Binding all components together is traditionalism; Sarz’s drum-laced soundscapes have come to shape contemporary Afrobeats because of how rural they sound — they are cousins to the forerunning Afrobeat, informed by those informal 5:AM lessons by his father on fuji, they traverse genuine and authentic pathways that met the producer prior to his ascension. “People instinctively say to me that they know when it’s my production,” Sarz ratifies. “The people who listen to me regularly say it’s in the drums, something about that makes them feel from song to song.”

Similar to the societal behaviours of both new-age, younger millennials and the generations that come after them in Gen Z, Sarz doesn’t tie himself to one act for too long as a producer. Sure, he can return to familiar territories, but his trajectory is unorthodox. From his 2010 breakthrough alongside Jahbless, he’s formed parts of pivotal Wizkid albums, including ‘Ayo’ and ‘Sounds From the Other Side’, elsewhere, he caressed releases such as Yemi Alade’s ‘Black Magic’, carving the song ‘You’, but he’s also roamed the realms of newer talent within the canon. “I have so much to give,” he says of his current methodology behind working with newer artists. “It’s better for me, sometimes, to work with a newer act than one that’s had so much success and sound built already.” Materialising Tems’ ‘Not An Angel’ — which grew to become a critical success and crucial career milestone — and merging his talents with collaborative projects with more experimental Nigerian acts like WurlD and Obongjayar; put simply Sarz can’t be placed into one box or stratosphere. He believes that to grow, he has to stay abreast of the new and emergent.

As the world grew curious about Afropop and Afrobeats, Sarz, alongside peers like Kel-P, P2J and Legendury Beatz, steered the future of the genres. In as much as the super-producer is lucid across our conversation, he’s also itching for innovation, his demeanour sharply animated as we traverse the topic. He’s eager to see the contemporary expansion of the Afrobeats genre and its related ecosystems — such as Nigerian pop and Afropop. Someone who is undoubtedly pushing the genre, to him, is Rema. It's conveniently been a few weeks since the release of his sophomore album ‘HEIS’ when I meet Sarz, and we briefly praise the project in communion. “He’s fearless,” Sarz says, pausing. “His decisions, how he moves across his career, he’s fearless, even his social media, he doesn’t care.” Also crediting Amaarae when asked, he believes that there are innovators like them within the space that will move as unconventionally as he does as a producer.

“If I had my way, no one would hear the music until it’s done,” he states. We’re broaching the subject of ‘Protect Sarz At All Costs’, his debut album which was initially scheduled to drop this week, but now the world will have to wait a little longer due to finishing touches being attended to. Sarz likes surprises, both in his artistic and personal life. The height of his spontaneous nature saw him purchase a house while living with Lojay during lockdown. The pair wanted to collaborate without potentially making family and friends ill due to quarantine. Managing to purchase and decorate the property under Lojay’s nose, the artist was in awe when finally shown the near-finished product. “I’m working on a surprise right now,” Sarz continues eagerly. Sensing my inquisitiveness he breaks the silence that follows by telling me to not think too much.

‘Protect Sarz At All Costs’ forms a near-perfect equilibrium, equal parts as local as it is on an excursion, it’s global in its curiosity but united under a pacified ear of globally Black diasporas. Big Sean’s classic puns adorning French-inspired Afrobeats, juxtaposed with the newest Nigerian dynasty member Asake’s Yoruba, the album is pan-African blurring nation and state lines. Still, its ubiquitous foundation of progressive Afrobeats helps to identify Sarz, articulates his origins, and modulates those in the context of a music industry constantly attuned with regions separated by oceans. Instant standout ‘Too Real’ sees Ayra Starr gliding across a groove and funk contorted foundation, her confidence and affirmations of being “one in a million” convincing as the horns croon behind her and mollified electric guitar strings. “I love the guitar now,” Sarz says of the song. “Ayra is such a star, she’s winning over the world song by song, she had to make an appearance here.”

At its core, Sarz wanted to preserve his legacy, as well as heal inner-wounds from his childhood in his debut album’s moniker and what it does as a body of work. “As a child, I never really saw my parents in love. My dad wanted us to be the best in school,” Sarz reiterates. “A combination of [the lack of love and expectations in school] made me kind of a black sheep and secluded, always relying on myself to figure things out.” During his beginnings in music, Sarz says he was almost “disowned” amid a lack of support from his father. His resilience led him to start his own academy, an non-governmental organisation helping producers in business materials and production facilities once he gained footing in the industry in 2015 — partnering with YouTube in 2022, and helping the careers of talent like Kel-P. “I never want it to be as hard [for young artists] as I had it,” he notes.

‘Protect Sarz At All Costs’ then, is a reflexive title. “It’s important that we protect these processes for the next kid in Ikorodu that probably has a laptop with a charger that might not work sometimes, can dream, and do it better than me.” The legacy of those on the continent, in Nigeria, outside of Western purviews, feels more real as he articulates this album. What it serves to say in its sequence of horns, or riffs, or strings, or basslines, creates a tangible footing that dreams can be achieved from back home too. It also reconciles experiences with an infant Sarz, through music he’s built refuge, community, a continuum of Nigerian prodigies, both a part of and in his proximity.

Although a self-taught perfectionist, the Sarz that sits across the table from me, with multiple decades of experience, finds determination in both failure and resilience. Part of this came in his recent expansion to DJing. “I started in 2019, I think after I released ‘Sarz Is Not Your Mate’,” he confirms. That six-track long collection of intrepid productions helps to demonstrate a gallantly intricate Sarz archetype — one that highlights his prowess as a canny architect of sound and rhythm. Take ‘Spiritual Riddim’ for example, with the hand-drums adornment of the song’s luminous strings slowly building across the bassline, crafting an balanced environment for the listener, perfect in pace. Many of Sarz’s songs exist in this medium, marching at perfect speed across ear-drums. He reveals, at this point, he had yet to learn DJing as a practice formally. “Spinall taught me,” he laughs. “I got booked for Gidi Festival so I had to learn.” Brutal lessons from the fellow Lagosian followed, where he was told multiple times that it would be impossible to learn in time. “Spinall told me to return the booking fee.” In three weeks, he learned enough to deliver — with the help of DJ Obi also — playing a trial session at one of Obi’s residencies for the cannabis celebration 420.

Read this next: Listen to a party-starting mix by Spinall

Loving the adrenaline that came from the pressure, he took on more bookings, but the toughest challenge came in an early pandemic Big Brother Nigeria booking. “I had my set ready, everything in-hand well in advance this time,” he chuckles, once again, his posture facing more forward as he narrates to me. “I couldn’t get any technical support at the party but nothing was working, I think there was a power outage.” Once restored, the speakers gave out on Sarz, with his set unable to be heard at full potential. The show’s team, who were playing background music in the meantime, and broadcasting live to millions of Nigerians nationwide, unknowingly manipulated the producer's set, leading viewers to believe that the music playing was his set, leading to clusters of complaints across social media. “That’s my worst experience for sure DJing, because it wasn’t even my fault.” Pausing, and leaning into production for much of the pandemic, Sarz returned to the decks earlier this year, including playing in Ibiza, making his Boiler Room debut, and stepping up to play Mixmag’s Lab LDN next week for a live Cover Mix recording. His ability to traverse the realms of Afrobeats, amapiano, Afro house and Nigerian pop means Sarz has more than cemented his arrival at his second vocation. “I know I can do this, and I know I can do it better than loads out there,” he says, his nurtured and culturally-binding confidence rising to the surface once more.

In his career, Sarz has let the music do the talking from behind the scenes. After more than a decade in the shadows, he’s more than ready to step into the light, cognisant of the new-found visibility that comes from being outside of the studio, crafting partygoers' experiences night after night. “I’m in a new world,” he says, ignoring a phone-call that briefly tempts his attention. “It opens me up. For the first time, I’m beginning to see fans that love me, not for the byproduct of what I produced. They bought tickets to see me, I’m now the star, that’s interesting.” He pauses, once again, contemplating his final utterance with me before we depart. “Let’s see just how far I can go with this now.”

Sarz's debut album 'Protect Sarz At All Costs' is coming soon

Sarz plays Mixmag's The Lab LDN on Wednesday, September 25, sign up for guestlist here

Nicolas-Tyrell Scott is a freelance music and culture journalist, writer, critic and podcast host, follow him on Twitter