Artists

Artists

Trevor Jackson's the punk-funk pioneer with a hand in dance music's aesthetic

It's always worth listening to Jackson

Although these days Trevor Jackson exists on the fringes of the mainstream music industry, he’s been a constant presence in dance music for almost 30 years.

As a young graphic designer in the late 1980s it was his work at Champion Records and elsewhere that, alongside the likes of Designers Republic, helped give the exploding electronic music scene a strong, graphic identity. In the studio, he was the enigmatic Underdog, one of the go-to remixers for hip hop and r’n’b, before retiring the name and introducing his next project: Playgroup. Hugely influential, Playgroup were the first modern iteration of the post-punk sound that eventually led us to The Rapture, Gossip, Gramme and many more. Playgroup’s sole self-titled album, released on Source, is an under-acknowledged classic, featuring a near supergroup of collaborators including Edwin Collins, Green Gartside of Scritti Politti, KC Flightt, Peaches, Roddy Frame, Gonzalez and dub master Dennis Bovell.

Concurrent to his work with Playgroup is Output, the label Jackson launched in 1996, which lasted for 100 releases before collapsing – but not before launching the careers of several of today’s current scene stars, among them Four Tet and LCD Soundsystem. Uncompromising in look and sound, it was typical of Jackson himself.

Today, he is sitting in a cafe just off a busy Brick Lane, sipping coffee. Recently he’s been issuing a stack of previously unreleased Playgroup tracks in a series of minimal, no-bullshit 12”s that had been gathering (metaphorical) dust on various hard drives and is keen to get it all out there, so he can concentrate on his real passion, looking forward – and making new music.

He’s recently started working in a completely different way than on all of his previous productions, and wants to clean the slate of the past. “I’d rather put all my efforts into a brand new record because once you’re into your forties, you don’t want to be seen as an old man playing old music,” he says. “That’s super important to me. Not that I have any issue with my age, but it’s exciting to me that I play on NTS and fifty per cent of the records I play are more challenging than the stuff the twenty-year-olds play. I’d rather be the old guy playing straight-up weird and challenging music rather than revisiting the past too much.”

Once Trevor Jackson starts, it’s hard to switch him off, and like his sometimes vituperative Facebook posts, he’s a sweary quote machine. I ask a question about the worst aspects of the internet and he’s off, winding down a path that alights upon one of his bêtes noire, Kanye West: “Even though I hate many aspects of the internet, I can’t keep away from it. Now, the network is international, which is exciting, but at the same time it destroys individuality. Everyone looks the same. Everyone’s into the same things. But it’s unstoppable and there’s nothing we can do about it. Fundamentally, most people are idiots and they need good editors. To me, the most important thing about culture is editors, whether it’s a magazine editor or a radio editor. It’s respecting people enough to have people choose the music for you, who you respect. Now we live in this democratised culture where everyone is a fucking editor. Everyone is a fucking expert. For me, I want to look up to people I respect to pick things for me. It’s like going into a restaurant and there’s meat, sauces and vegetables there and you make your own thing. I’d rather have a fucking chef do it for me. But this is the culture we live in now. And the respect to connoisseurs and editors has gone because everyone thinks they’re an editor. We live in Kanyeworld and he represents everything that’s bad about contemporary culture. Everything.”

About 18 months ago, Jackson put out an album of new music entitled ‘Format’, originally released on a bewildering variety of (yes) formats from simple 12” single to cassette tape and minidisc. I ask him how much downloading has devalued the physical aspect of music – if it has at all – and he’s off again, filled with the certainty of an evangelist. “How long we got to talk about this?” he begins. “When I did ‘Format’ it was all about the importance of music existing physically. And it wasn’t just a fetishistic thing about the minidisc itself, it was about trying to make it as complicated and as difficult as possible for people to get those items, right? Because the process of buying the music is as important as having the music. When I was younger, Tim Westwood used to play this Isaac Hayes break, ‘Ike’s Mood’, and no-one knew what it was. We were like, ‘What the hell is that record?’ They wouldn’t have it in your local WH Smiths. You had to find it. I think I eventually found it in Record & Tape Exchange, but that journey was quite long. No internet then. So you’d have to go to record shops and ask people, or even write letters. And then that feeling you’d get when you had it in your hands! I’ve got maybe thirty to forty thousand records and I remember where I bought most of them; and whether I bought it in my local Virgin Megastore or flew to Hamburg to buy a rare MPS record, that journey is fundamentally important – so when you take it out of the equation it’s devalued. It becomes like wallpaper. Disposable. The more convenient you make things, the more disposable they are. It’s a fact, isn’t it?”

The nearest brush Jackson has had with crossover success was with Playgroup, his failed attempt at a pop record (or, more accurately, his specific version of pop). “Philippe, the guy who ran Source, signed me because he thought I was cool,” he says. But for Jackson it was a chance to do things differently, to spend money on great studios and work with musician heroes and talented collaborators. “The turning point in making that album was meeting Edwin Collins in his studio in West Hampstead,” he explains. “I said, ‘I really want a Prince-style Van Halen-ish guitar on ‘Number One’,’ and he said, ‘Oh I’ll speak to Roddy Frame [of Aztec Camera].’ So Roddy came down and played guitar. Then I said, ‘I’ve got this other track that needs a vocoder’ and he said, ‘Oh, I can do that I’ve worked with [US composer and Zapp founder] Roger Troutman’. It was literally like that. After a disaster in New York we were redoing ‘50 Ways To Leave You Lover’ at Edwin’s studio and he said ‘Let me speak to [reggae guitarist and producer] Dennis Bovell’, so he came down and helped put some chords on it. It was a really natural process, mainly through Edwin’s mates.”

Sadly the record never achieved what he hoped, or what it deserved: a salutary lesson in the daily heartbreak that is the music industry. “I can’t deny that it did frustrate me that it didn’t do as well as it could’ve done. I was partly to blame because I didn’t want to play live. I didn’t even want to DJ. I told them I didn’t want to go out and DJ to support a predominantly live record. I didn’t see the point. Having said that, expectations were high. ‘Number One’ didn’t get picked up by Radio 1 because they thought it was too retro. And then that was it: the bottom fell out of the whole project. Literally two months after the single didn’t make it to Radio 1, everyone apart from my manager dropped me. The record label completely lost interest in the project. That’s the power of Radio 1. But for me it was a benefit, because through good negotiation, I got my record back, so now I own the masters. For me it was never about selling records, it was about making the record I wanted to make.”

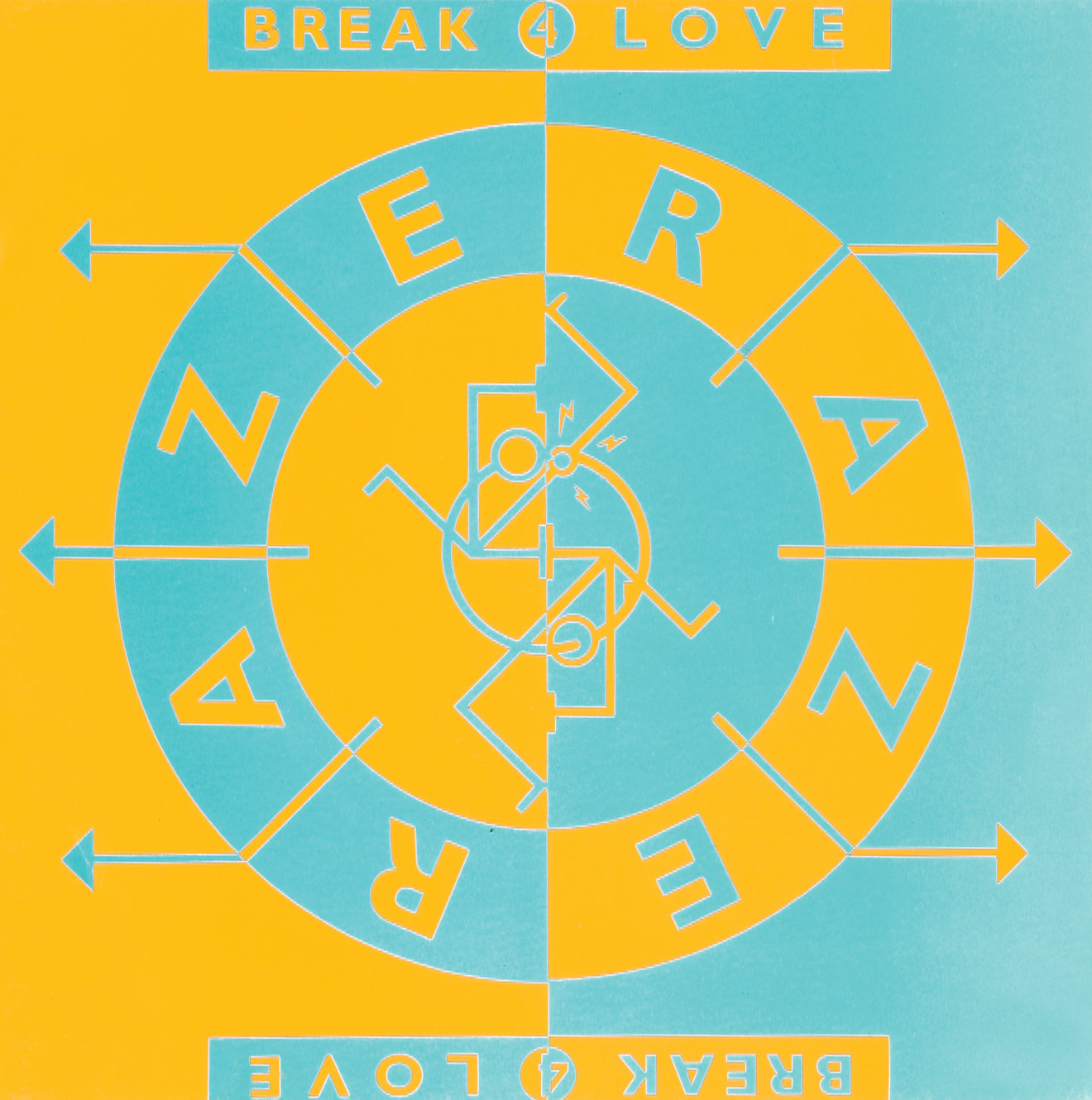

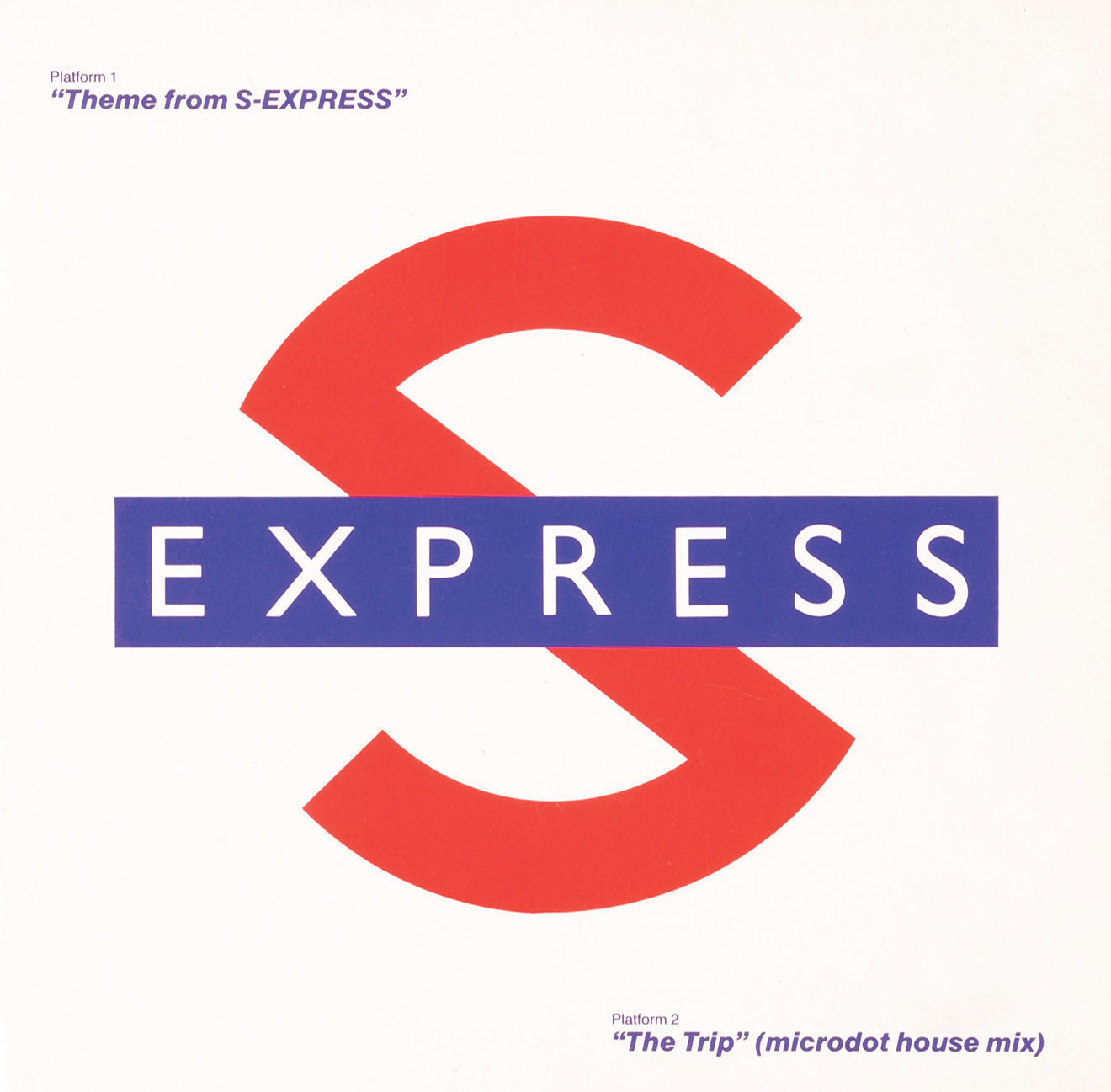

At the start of his career, Jackson was known for his design work. He’d studied at Barnet College and his principal aim was to become a sleeve designer. His big break came while still at college when he took his portfolio in to see Mel Medalie, head of Champion Records, and offered to do the first few for free to prove himself. His work for Champion and, later, scores of other artists and labels, helped create a look for house music that was brash, cheeky and splashed with primary colours (it’s also in stark contrast to his current work, which is often abstract and monochrome). “It was a reaction against most of the people designing sleeves who were in their forties and had never been to any of these clubs. They used to take a photo of the artist, add some type and it was all really boring. So I was like, “Fuck that, I’m going to do something really crazy with it”. And it suited what was going on. The Raze ‘Break 4 Love’ sleeve was a man and woman doing a 69, S-Express was a skeleton with a huge dick, which is a train. Very juvenile, but that’s what I tried to do all the time.”

It’s difficult to describe exactly what Jackson is, since he’s producer and DJ and also a graphic designer (and still very active in all of these disciplines). How does he see himself? “The thing I put the least amount of importance in my life to is DJing. But when it goes well, it’s so enjoyable to play music you love to other people who are enjoying it. I don’t perform live so it’s a fantastic feeling. But that feeling is quite short-lived, whereas the other things I do, like designing something, that project might live with me for years, or even decades.

“I would put more emphasis on my DJing but so much of DJ culture, I just don’t want to be part of. The best clubs I ever went to were the ones where you never even saw the DJ. The most important DJs for me – Colin Faver and Eddie Richards at the Camden Palace – you could just about see the tops of their heads! So if I can go to a club where I can see the crowd but they can’t see me, I feel more comfortable. I’ve always felt uncomfortable with attention in that way... but I love playing music to people. So that’s a difficult thing for me. That whole Norman Cook, big beat thing, that fucked things up, because the DJ became more important than the records. And I know there was Ron Hardy and Larry Levan etc, but it was still about the music. I’m not a performer. I don’t want to be a performer. When I play I can be pretty bloody good. But… I can be bad as well.”

Maybe. But never, ever boring.

Playgroup ‘Previously Unreleased’ is out now on Yes Wave Records

Images (in order of appearance): Raze 'Break 4 Love', S-Express 'Theme From S-Express', NTS presents 'Palindrome' (2014), Playgroup 'Number One', 'Format' 12 different formats (2015), 'Trevor Jackson Presents Metal Dance: Classics & Rarities 80-88 & 79-88', Playgroup 'Make It Happen!' (2000), Four Tet 'Dialogue' (1999)