Scene reports

Scene reports

Parisian collectives are building an underground scene outside of the clubs and city

Sound of the suburbs

“Don’t worry, the police won’t disturb us tonight”, says Sina, a brown-haired DJ in his late twenties, a twinkle in his hazel eyes. “No-one cares what goes on here – we’re in Bobigny”. He’s probably right: for the past 10 minutes, we’ve been driving through a seemingly endless grid of industrial buildings and warehouses, without a house in sight.

It’s a warm Friday night in spring in this north-east suburban area of Paris. Tonight Subtyl, one of the most dynamic techno artist collective to emerge from the fringes of the capital in recent years, are hosting one of their renowned illegal warehouse events. Phase Fatale is headlining, before heading to Berghain.

Tonight’s spot isn’t the usual derelict 19th century brick building. Instead, it’s a triumph of 80s corporate architecture: plastic cladding, small windows, a grand entrance hall complete with fake palm trees and unremarkable grey linoleum underfoot. Above us are two floors of offices, making it a fairly unexpected playground for revellers. But a few steps further and there’s a sudden shift of atmosphere, and a familiar buzz in the air. And there it is: a 50 feet tall storehouse, its metallic walls whirring and rumbling as the structure fights to contain the harsh sounds of industrial techno.

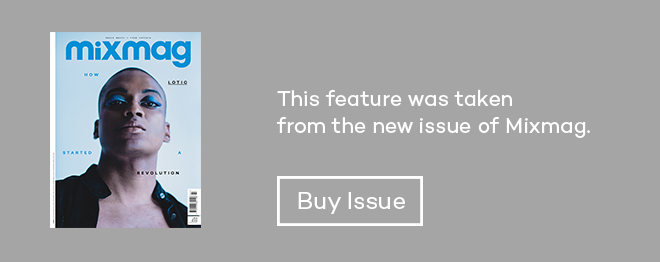

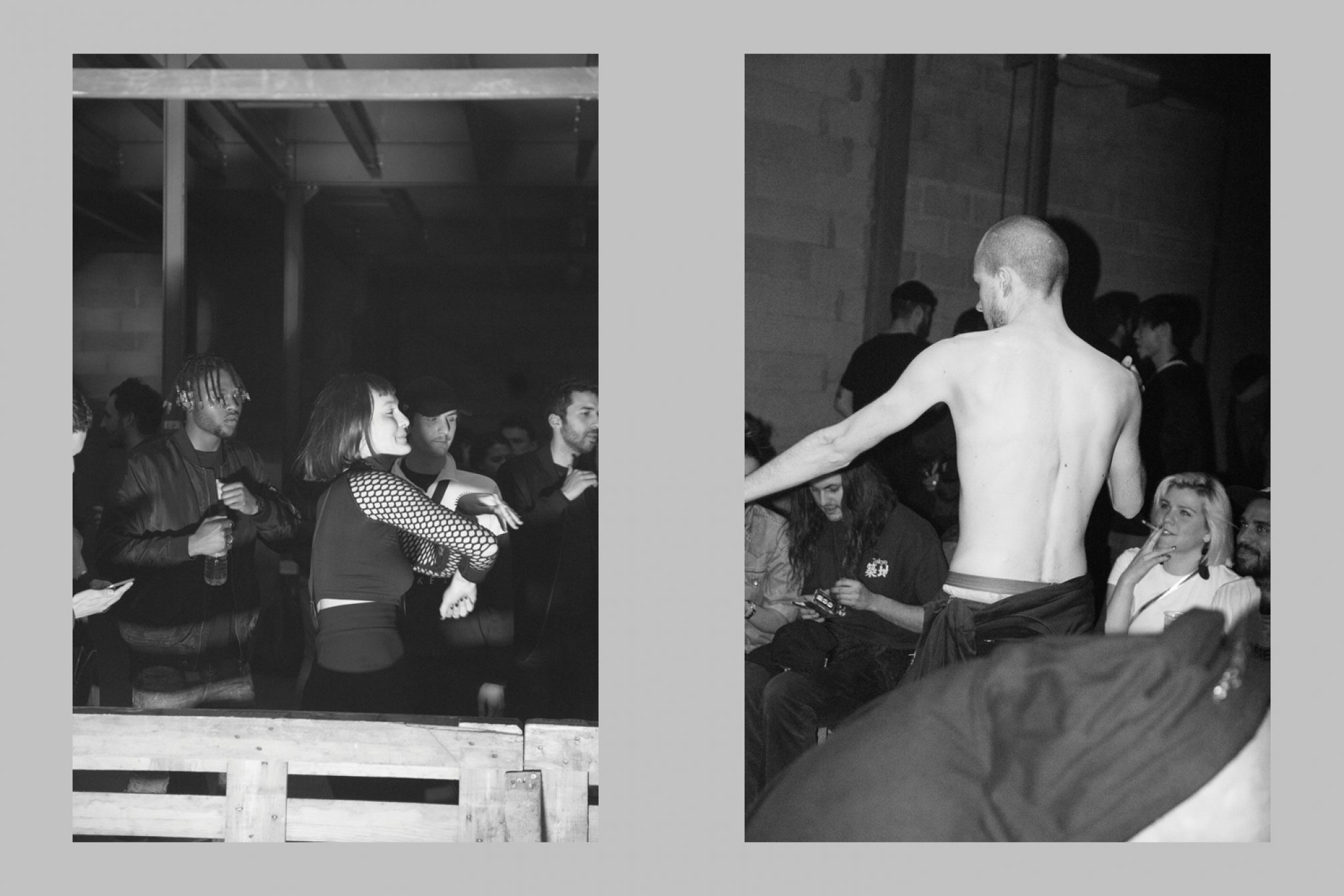

Behind the decks in a bright pink dress, Parisian DJ Miley Serious swirls, swinging her arm around in bliss whilst playing dark, high intensity beats to a cheering crowd: a mix of leathered-up techno-heads, art students, all breeds of maverick and everything in between. The production level is every bit as good as a club night, with high-end lighting rig, smoke machines and state-of-the-art holographic 3D video set-up. Bar staff and public alike are smoking inside. Among them paces a benevolent security guard, unfazed.

“We rent the space, we try to be clean and friendly,” explains Sina. The collective he co-founded, Subtyl, is one of the numerous crews that have emerged from this semi-legal party scene over the past six years. Many of the Parisian collectives highly active today – La Mamie’s, Cracki, Haiku, Distrikt – follow the same model. “When we started, there was no guest list, no backstage, no DJ guest, just local artists. We created something new, that incited other people to do similar things in their own way”, he adds. Their strong support of local artists bred a new generation of underground talent: Voiski, François X, Antigone and more recently Kas:st, AZF and Molecule all started in these circles.

The acid-heavy sounds playing tonight aren’t without similarities to the hardtek and hardcore found on the marginalised free party scene. But this movement is different. Forty Parisian collectives, young and old, gathered this year to form SOCLE (Syndicat des Organisateurs Culturels Libres et Engagés), a union and support network that lobbies for local authorities to allow and recognise their events. One of its founders, seasoned journalist and promoter Antoine Calvino, explains that 20 years ago, raves were “interludes of freedom, a unique moment out of time. It’s their severe repression that led them to become free parties, pushed further outside of cities”. Local collectives now aim to bring a modern French version of those raves back into town, one that encompasses house, techno, world music, theatre, circus and the arts, that celebrates freedom and social diversity. Their manifesto reads: “The bubbles of poetry we create in our parties are a necessity in the ever-harsher, normative environment of our everyday lives. Let’s work together to preserve them”.

Although they cater to a crowd eager to find the freedom, affordable prices and thrill that regulated clubs don’t always provide, their events don’t aim to compete against the existing institutions. The promoters believe that several of the city’s clubs – Badaboum, La Java, Concrete and the Rex, among others – continue to play a vital role in Paris. “Without them, there is no scene”, stresses Louis Benet, Subtyl’s artistic director.

Like many of its peers, Subtyl is a non-profit organisation: every penny they earn from their events is reinvested into the project. But if their work is driven by passion, they have their feet firmly on the ground. Sina is inspired and informed by the dreamers who threw the first raves in the French capital: “To understand why they disappeared allows me to prepare myself for the challenges to come”.

It’s not the first time Paris’ suburbs have entertained some of the most electrifying gigs in town. Forty years ago, the debauchery of La Main Bleue in Montreuil would easily rival the heydays of New York’s Studio 54. Twenty years later, as the fallout from the second Summer of Love spread across Europe, the outskirts of Paris hosted some of the fierces raves in town.

Today, once again, these urban outskirts welcome a new, burgeoning scene. They offer a space for young music lovers with a vision to experiment and build an identity outside a crammed urban network, where the pressures on real estate are rife and only the biggest clubs can survive.

But Subtyl aspire to legality and recognition. And they are about to reach their goal: the collective recently hosted a night at Rex Club, and the next stop is Concrete. “We’re not a club, not a rave, not a free party – we’re a mixture of all those things,” concludes Sina. He admits he’d like to own his own venue one day – if he could run it on his own terms.

The sun has risen on the warehouse, but the dancers are still revelling, circulating endlessly between the dancefloor and the indoor chill-out area; the night won’t end before 8AM, and “maybe later”. As we head back outside, the first rays of the sun casts the shadows of a moving, intertwined and unaware couple on the wall nearby. The careless abandon of their embrace is a stark reminder that beyond Paris’ old stones still burns a relentless, irreverent passion.

Marie-Charlotte Dapoigny is Mixmag France's Digital Editor, follow her on Twitter