Features

Features

How the #BrokenRecord campaign is fighting to fix the music industry

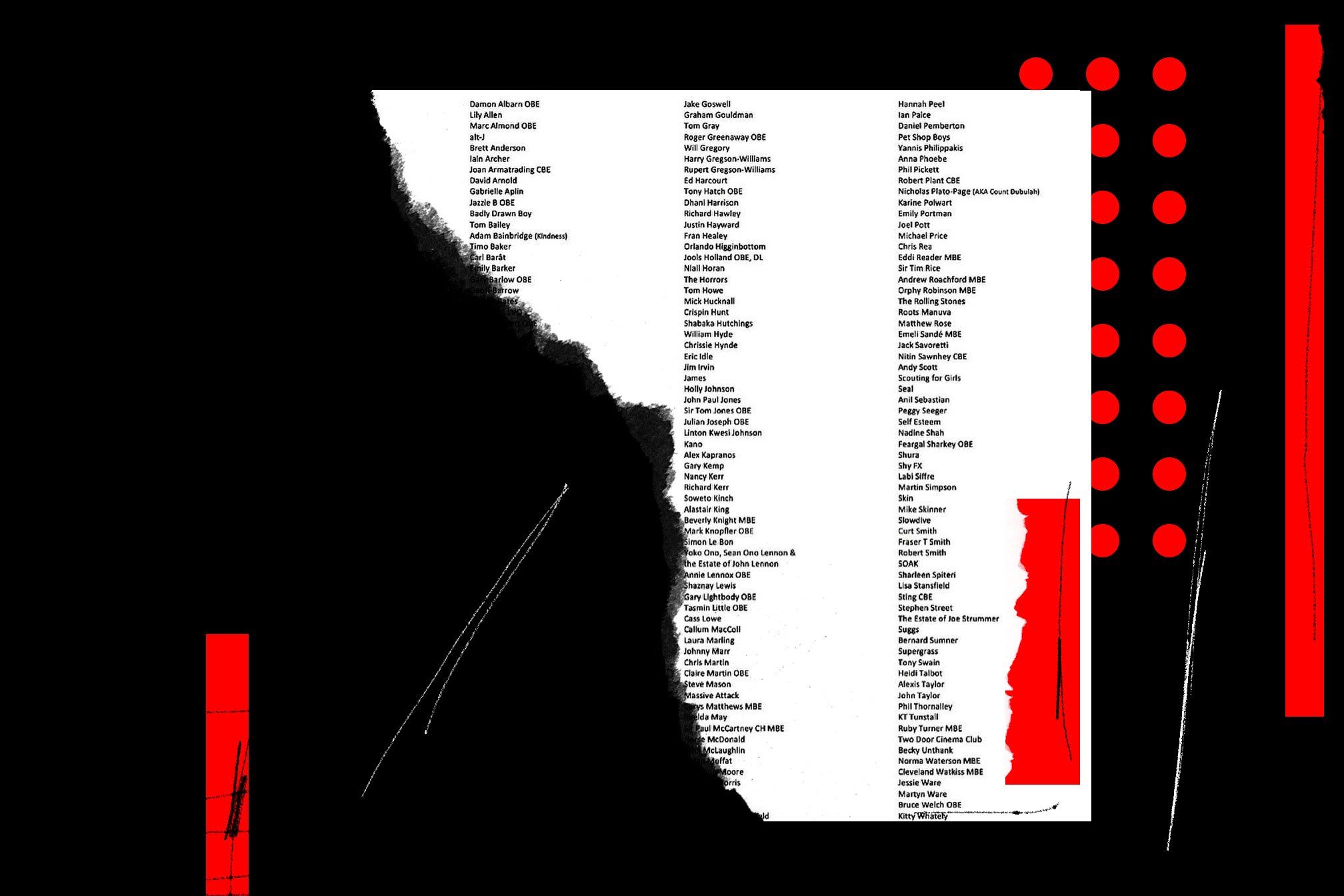

It is vital that the economics of the music industry change to challenge exploitative power, support independent artists and benefit society. Tom Gray, founder of the #BrokenRecord campaign, explains what can be done

In order to make the music industry more equitable, the economics must be understood and contextualised for the Black music creator. The options available to them in an increasingly DIY-centric consumer space are broadening and, in some cases, can be overwhelming. Musicians, whether with or without teams, are invariably challenged to make the right choices when retailing their art or face the risk of being tied to financially damaging arrangements.

I asked Tom Gray, fellow musician and fierce advocate of rights for songwriters and musicians (and the new Chair of the Ivors Academy), to outline what he’s been campaigning for from the perspective of all musicians, but especially Black musicians from working class backgrounds who have arguably, at least from a historical perspective, received the harshest financial outcomes.

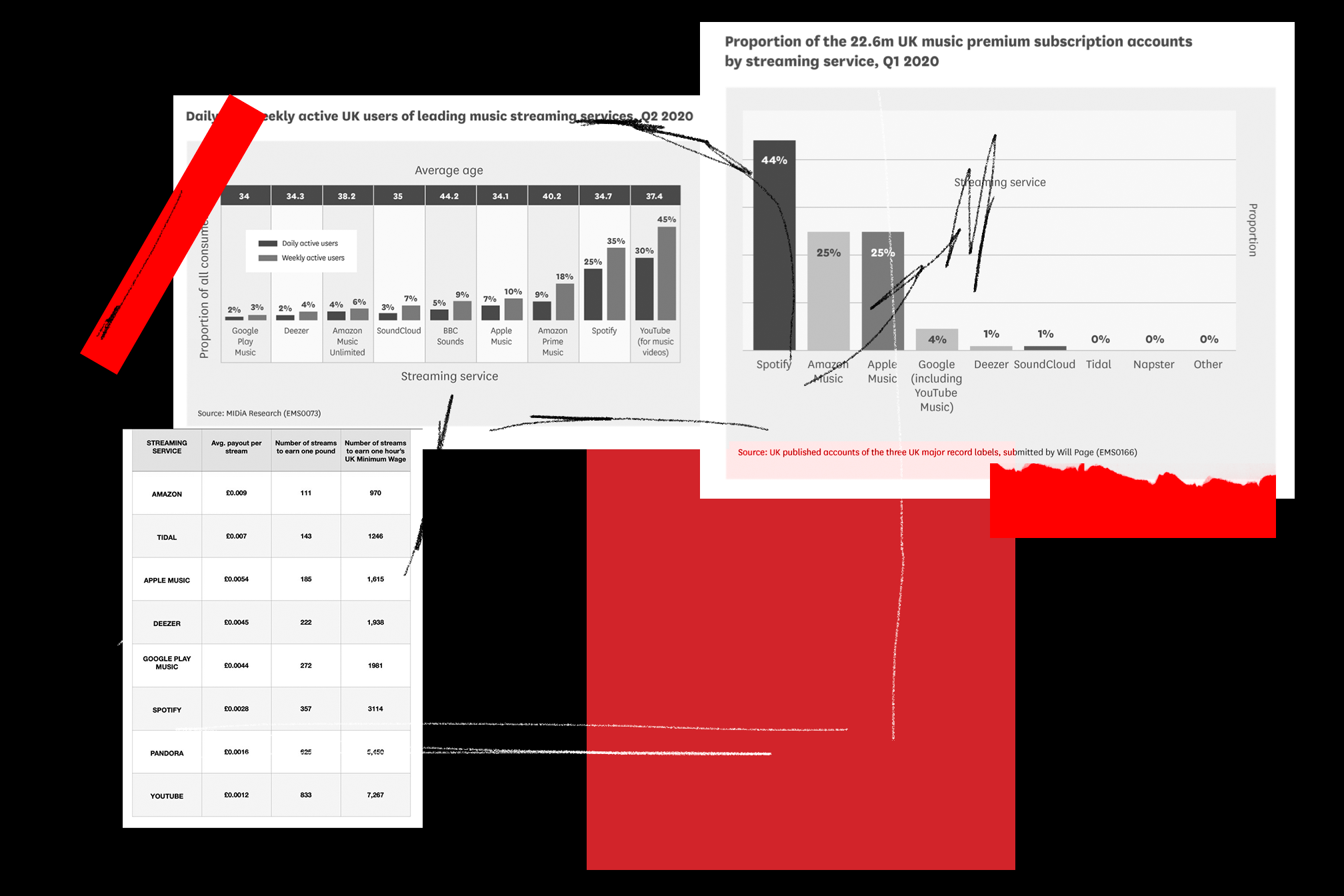

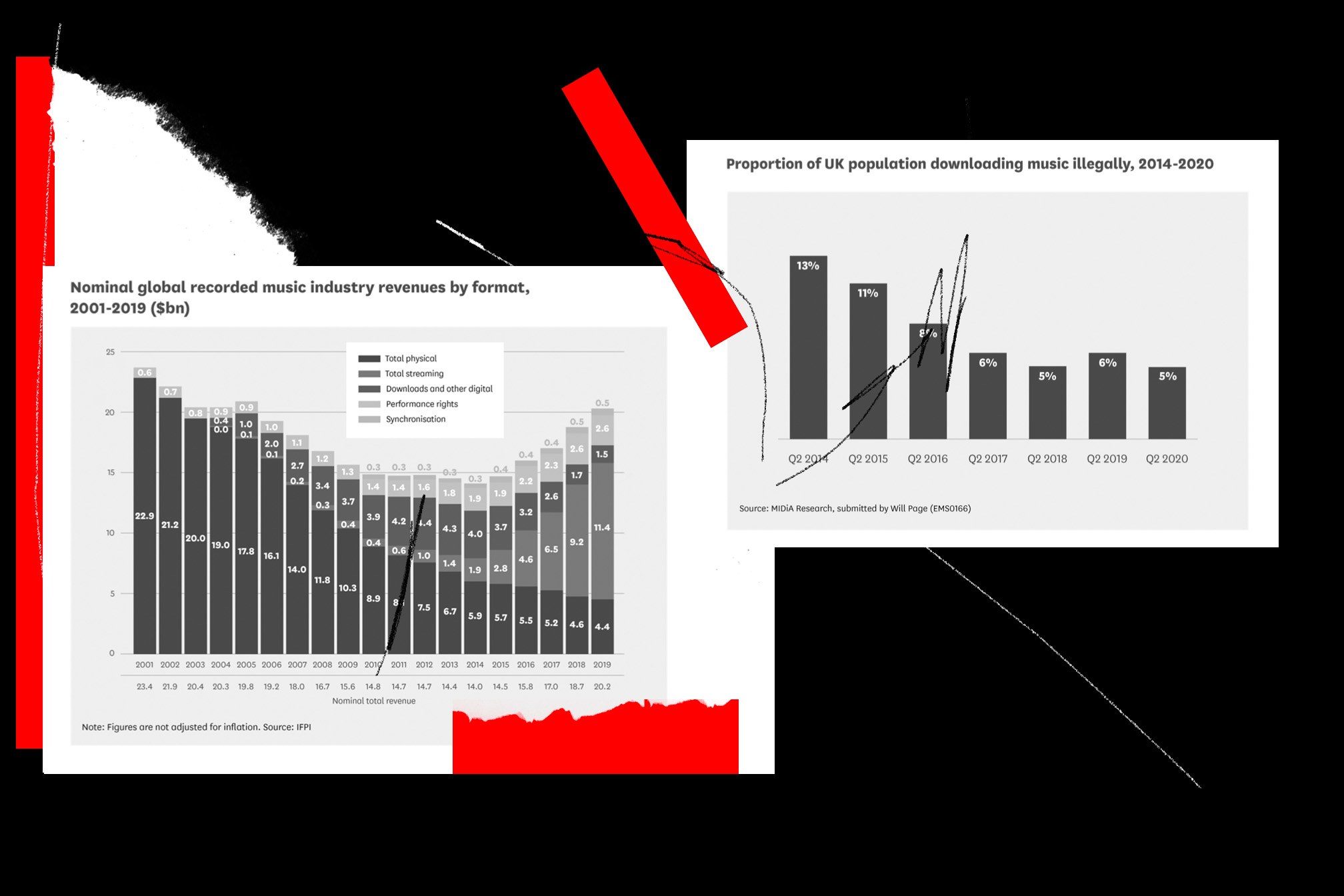

I started #BrokenRecord because everyone was struggling. COVID created a perfect storm whereby earnings from recorded music were left bare. 62% of musicians reported earnings below £20,000 per annum in 2019, which means many live below the poverty line and many more need state benefits to get by — and that's with live performance income. And yet we’re told that 1 in 10 tracks streamed on the planet originate in the UK. Which ought to mean that a tenth of the now $15 billion streaming industry ought to be flowing into the UK. One and a half billion. If you gave every single professional musician in the UK an annual cheque for five grand, you’d still have more than a billion left over every single year. There is more than enough money in music for us to make it fairer. After all, the major labels make around a million from streaming every single hour.

We should be able to say to the kids who are already chucking their tracks up on YouTube that succeeding in this industry can mean a long and healthy career. If you put everything you have into your artform, and you are talented and have beautiful, brilliant, inventive ideas, the least we can do is have your back.

Sure, music has always been a precarious life. You must hustle and occasionally you are part of a goldrush, but simply because an industry has always been unregulated and inequitable it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be better, does it? We shouldn’t be resigned to inequality and unfairness. The Black community shouldn’t need to feel like it has to go even further to overcome an already uneven playing field. Working class kids remained uneducated until the Education Act of 1944. People always accept their circumstances, but it doesn’t mean that as a country we can’t do better. We can change the law. We can do better for music-makers. The tired cynicism of “that’s just how it is” has had its day.

Read this next: Almighty influence: Why Gospel music deserves more support and investment

While recognising that broader ‘access’ to the market has allowed British Black music to flourish, breaking down a lot of hierarchical gate-keeping, there still isn’t a truly open playing field in music. It is bad for everyone because it denies opportunity to nearly all, it stifles innovation, and it keeps the bar low and slow for ethical and sustainable progress. It leads to getting stuck with lazy and unfair norms. Sure, there’s plenty of access - I can distribute my music in the blink of an eye - but the piece of the market that we are all challenging for is tiny compared to what’s out there. We’re fighting for a beach on a colonised island. Even if you’re doing well, you could be doing so much better.

Let me explain. Fully independent “DIY” music accounts for just 6% of the value of the market. Millions of independent creators uploading their work every day, vying for just 6% of the value. At the present rate of growth, it will take between 25 and 30 years for this segment to challenge the status quo.

If you look at Spotify’s Global Top 50 tracks, on any given week, typically over 80% of the tracks are owned by a major label. If DIY accounts for 6% of the market, and we know there are many millions of independent creators, only a vanishingly small percentage of artists making any real money from streaming can possibly be fully independent. Though I wish it were not true, trailblazers like AJ Tracey are far more the exception than the rule. I do not wish to stifle hope, far from it, but if you are young, Black and fully independent, you are not only going to have to clear the huge obstacles you may face in terms of inequality and racism, but also a system that is heavily stacked against all but a few. Also, and I don’t think this gets said enough, Black creators make every kind of music, not just “Black music” genres. Just like there’s plenty of white kids making hip hop. I was a white kid (albeit a strange northern combination of Roman Catholic and Jew) whose life was changed by his love of the Blues. But, in my view, we shouldn’t be overly concerned with genre. Any solution for what’s wrong has to help the most musicians possible. Maybe I’m wrong, but it’s my belief that if we help those on lower incomes, if we help those kept outside the mainstream and outside the room, and if we challenge old, exploitative power, we can all benefit as a society.

There is a huge amount of work that needs to be done to examine how monopolised market power disadvantages independent music, affects playlisting and how the licensing deals between platforms and labels entrench that power too. This is one of the reasons why we asked the Prime Minister for a referral to the Competition and Markets Authority, in the hope to create change and, one day, a free market that favours the brave. Unfortunately, although there are some great facts in it, the report fell badly short.

Spotify tells us 1% of artists’ work generates 90% of the income, but how much of that income even gets to the artists, the performing musicians, producers and songwriters. How many of the 13,000 catalogues, which Spotify assure us earn over £36k per year, pay an artist one penny? We don’t know and no one will tell us. Clearly session musicians, the most vulnerable members of our community, get nothing from streaming. They get paid by radio, but radio is riding the steam train into history. Songwriters get the thin end of the wedge despite originating the work. Producers, although sometimes paid decently up-front, seem to be lost in an accounting nightmare to receive any back end. There are clearly many creators working today negotiating size-able front-end deals, but it won’t and can’t last forever for any individual. Nothing lasts like royalties...They can keep arriving until 70 years after you die.

Artists are, as ever, the most likely to find themselves in an unfair deal. Of course, there are licensing deals, distribution and profit-share deals available, but any realistic overview of the market and the practices of the companies who are the biggest players reveals that the most common deal being done - associated with significant value in 2021 - is still the Standard Record Deal, the recoupment deal. The deal which puts all advances, recording costs, etc against the artist’s earnings. If you come from a poorer background, the enticement of cash upfront is very strong even though it might lead to harsh contractual terms.

Recorded music at the beginning of the 20th century paid nothing to performers. The vested interests of manufacturing got in front of copyright law and managed to deem the printer of the plastic to be the author of the recorded performance - not the performers. Every measure since then has been a struggle to return power, control and value back to the creator of the performance. By 1958, The Drifters were being paid 2% and by the end of the 20th century, when Prince was challenging his contracts, artists in ‘standard recording deals’ were getting closer to 18%. Though the companies were still only paying on 90%, keeping 10% for ‘physical breakage’ - the mythological damage done to vinyl in transport which did not really affect CDs. Another 20 years later and we still hear labels are doing 18-25% deals every single day. And, more often than not, those royalties will be kept by labels against debt.

.Read this next: What are perpetuity deals in record contracts? And why they're a problem

One of the biggest drivers to the creation of a royalty payment system was the life of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, an Black English composer who died in 1912. His most famous work 'Hiawatha's Wedding Feast' sold hundreds of thousands of copies. But he died in financial ruin triggering the decision by the British publishing community to never let this happen again. PRS was created as a result. You see, royalties are the lifeblood of careers. They keep food on the table and the wolf from the door. That’s why #BrokenRecord has campaigned for something called ‘Equitable Remuneration’ (ER), to ensure some royalties in the pockets of the whole recording community irrespective of genre or contract. Possible alternative models which simply redistribute income like the ‘Artist Growth Model’ are rightly treated with cynicism by creators, because changing which label gets what, doesn’t remedy whether you get paid in the first place. Whereas, with ER, the performer right from broadcasting would be applied to streaming. Performers from every background who have worked with labels going back as far as you can imagine will be ensured some payment for the first time. Even if there are a few losers, I believe this alone makes it worth it. After all, presently around 70% of streaming is catalogue listening. We all become ‘catalogue’ eventually. The music you make when you’re 21 can support the music you make when you’re 30 or 50: it can help your kids even after you die.

I’ve heard people try to position ‘catalogue’ artists as the old, white establishment, but 'Straight Outta Compton' came out 34 years ago. ‘Catalogue’ is simply defined as any track which has been out for longer than 18 months. The promise of having a valuable catalogue with an established audience and a decent share of royalties offers the only way to have a realistic, rewarding, long-term recording career in the 21st century. It’s easy to pretend that everything is fine if you can hustle some money now, but shouldn’t your work keep paying you if it keeps being listened to? Because of those old, crappy deals, much of ‘catalogue’ is holding up the old, inequitable system. All that has to change. That’s why we’ve campaigned against ‘Life-of-copyright’ contracts. These are contracts that last for 70 years. If we can get our rights back after a shorter time, it can erode the major catalogue monopolies giving independents far more market access and make British artists a little wealthier.

Economics textbooks teach that unregulated markets tend towards monopoly – that much is clear to see. Universal has well over 30% of the market: that is a monopoly position – but also something called ‘rent seeking’ can happen. You can tell it’s a critical term, who likes to pay rent after all, but it means when a corporation gains added wealth without any additional work – they get more for nothing. The majors used to be manufacturing companies with factories, distribution companies with complex logistics, they used to have A&R scouts in every metropolitan area. They had extraordinarily high costs which they no longer have, yet they continue to keep *at least* 80% of the money and still put recording costs against artists’ earnings. This excess of profit in the market is what should be heading into the pockets of enterprising music makers everywhere.

Read this next: Why we started the Black Artist Database

One of my proudest moments for #BrokenRecord came the day that Sony announced the forgiveness of unrecouped debts. But what really hit home was when I was contacted by the manager of a brass band from New Orleans. Most of these fellas are now in their mid-60s to 70s, a couple have sadly passed away. He got in touch to thank me because our work meant a few old men who have devoted their lives to music, who started playing together in their local Baptist church marching band will get paid royalties from their back-catalogue for the first time in their lives. Of course, this change also came on the back of the brilliant work of the Black Lives Matter movement, pointing out that because Black performers make up such a large percentage of music history, they have been disproportionately exploited by unfair practices. Thankfully, Universal and Warner now appear to have stepped up to do the same as Sony.

If we fix this stuff, artists won’t have to tour as much which is better for the planet, money can flow back into the communities where the music we love comes from. The years of exploitation without reward can start to heal. Independent music can thrive just as independent film did after copyright law was changed to their benefit in 2003. Music has an extraordinary power to be a force of social mobility and social good in our inner cities but also everywhere else. Music cuts across class, region, ethnicity, gender, education, and wealth. It knows no bounds, but we have lost our way. The mistakes are many, going back over a century, but we’re back to wild profitability. Surely in this renewed period of self-reflection over our ethics and our sustainability, we can’t make any more excuses for leaving so many brilliant creators behind.

Tom Gray is a musician in the band Gomez, Chair of the Ivors Academy and campaigner, follow him on Twitter