Culture

Culture

The art of club design

The brains behind Printworks, AHM and Blitz Club explore the art form

We spoke to three of the most innovative club designers of recent years, from Beirut, London and Munich.

Simeon Aldred - Printworks, London

As creative director of The Vibration Group, and drawing on his extensive experience creating and running festivals and large-scale public events, Aldred’s team has partnered with festival owners and culture curators Broadwick Live to turn Printworks into a standout London clubbing destination, and recently designed and opened its live music space. While he conceptualises the events as an indoor festival series, it has a wider function as a “multi-level culture space” for everything from exhibitions and theatre to the Royal Ballet.

Learn more about Aldred’s work on Printworks at vibrationgroup.com & broadwicklive.com

Rabih Geha - AHM, Beirut

Rabih Geha, who runs his own architecture firm, is responsible for some of Beirut’s most distinctive clubbing venues in a city that is often at the cutting edge of club design, including Ahm, Überhaus, Off & On and the recently opened 2 Weeks, as well as various other residential and commercial projects. Drawing on Rabih’s fascination with storytelling, each club offers a unique, multi-sensory experience to its club-goers.

Visit rabihgeha.com to learn about AHM, Überhaus, Off & On and more

David Muallem - Blitz Club, Munich

One of the founders of Munich’s Blitz Club, David Muallem, believes that more clubs should be conceptualised and built by DJs. The 39-year-old has been DJing for quarter of a century, and 10 years ago joined the then-new Bob Beaman club as its creative director. His team of five long-time nightlife friends launched Blitz Club a year-and-a-half ago, fully implementing their vision of how a nightclub should be from the soundsystem to the design.

For more information on Blitz Club’s cutting-edge techno lineups, head to blitz.club

What are the priorities when it comes to nightclub design, and which are the most important? Has this changed since you began this work?

Simeon Aldred: There are amazing experiences on every street corner in London. It’s no longer enough to say that we have brilliant sound and lighting at our venue; our audience want a lot more. They want to be able to explore the whole building and feel like equals. For most of our shows, a VIP area is not required. Our audience wants a democratic experience in an amazing building that’s raw and ready to be explored.

Rabih Geha: For me, a nightclub is an overcrowded space where everything has to function perfectly together. There’s a lot happening in a club, and it’s vital to be able to welcome one to two thousand clubbers for a few hours of the night seamlessly. Ultimately, the number one priority is the experience, the story, and the narrative: the sensory immersion. That’s something I tried to generate with the whale at Überhaus that swallows you in, the sea journey you embark on in Ahm, and the secret barbershop door of Off & On that hides a world of glamorous taboos. There are also separate priorities involved, ones that are invisible to the club-goer. The vital one is designing a space that everyone can flow through.

David Muallem: So far, my projects have been centred on the communal experience of dancing – one of the oldest rituals of mankind. The quality of sound should be an absolute priority. Once you’ve paved the way for out-standing sound quality, you already have a good chance of creating an exceptional nightclub. Design-wise, the size of the dancefloor should be greater than other areas and separated from the bars. The DJ booth should address the needs of artists and shouldn’t put them too centred for people to focus on the music. Think of the DJ as part of the ritual, rather than a separate entity.

We’ve heard it said that the primary purpose of a nightclub is ‘sensory immersion’ – how accurate is that?

SA: Totally accurate, but sensory immersion is no longer just about sound and light. Our audiences want great food, wider-ranging bar options, and safe spaces to rest and relax whilst enjoying the 10-hour line-ups that we have here at Printworks.

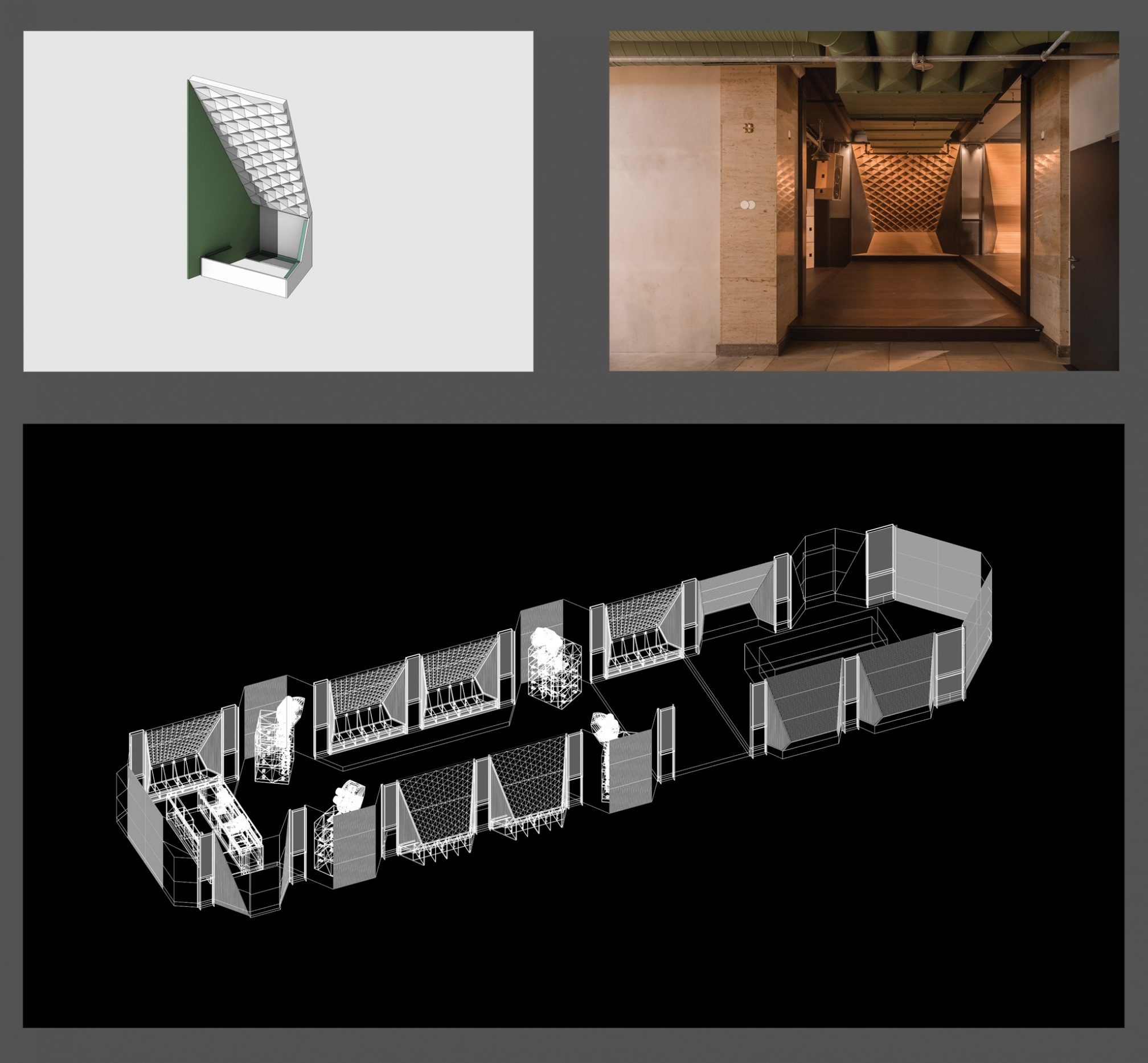

RG: Nightclubs are spaces of experimentation for architects. All the projects I have worked on are designed as a narrative immersive experience: an artificial world isolated from the exterior. Ahm draws inspiration from the surrounding Mediterranean sea. Mast-like structures and linear lighting dominate the space, referring to Lebanon’s seafaring ancestors. The experiential story of Uberhaus starts immediately through a walkway flanked by containers. Finally, you turn a corner and there it is, the ribcage of the whale that has sucked you inside it, leading you to the climax of the story: the dancefloor. Inspired by the speakeasies of the early 20th century, Off & On’s sleek barbershop façade is just a front for the more taboo and ‘prohibited’ secret that lies beneath.

DM: It’s pretty accurate in my opinion, especially when thinking of sensory immersion as a tool to make people let go through the music. As mentioned before, the primary purpose of a club to me is making people dance together. Sensory immersion is one of the most, if not the most, important parameters to make this happen. Sensory and sonic immersion have always been at the core of my endeavours when building clubs. Create the perfect acoustic space with a state-of-the-art soundsystem, make sure people can get lost in the music together and you will be rewarded with an outstanding club. It’s as simple as that.

How have major developments in sound and lighting technology influenced nightclub design in the past couple of decades?

SA: Tech is only ever as good as the operators using it. We employ some of the best sound and lighting engineers from around the world. Tech that’s now on the market includes kinesis motors, LED screens, lasers and phenomenal sound, which gives production designers and operators a massive palette to work with for up to 10 hours.

RG: Today’s technology basically lets us do anything we want. But personally, I am a purist in my designs. I do not seek technological prowess. I do, though, try to achieve a noticeable effect, a chosen mood and an immersive experience. For Ahm, we recycled electrical posts and turned them into 40 fairy-like masts, while 50 containers, stacked like Lego, make up the thoroughfare and access space of Uberhaus. The entire whale structure is built of 15 ribs, patterned with colour-changing LEDs.

DM: I’ve always been fascinated by traditional nightclub technology. There are so many things you can create through modern LED lighting systems, but I haven’t seen anything replacing traditional theatre and nightclub light installations. At Blitz, we have focused solely on traditional elements. We have several ACL moving head rigs, a Clay Paky Astrodisco, Svoboda light stage rigs, neon pipe rigs, as well as classic projectors that we use in the same way modern lasers are used.

How important is it that a club reflects the city/country/heritage of the area?

SA: We have an international audience and line-ups, but the core of what we do at Printworks feels very ‘London’ to me.

RB: Context is key when creating a story. It’s a vital starting-point alongside the initial design brief. Each club has an individual identity. I tend to draw upon my subject, which in essence is the project, and its surroundings. To understand it better, I always put myself in the space – the area, the street, the building – and then create a visual narrative through my design and architecture, while ensuring it is in sync with the client’s vision.

DM: I don’t think it’s important at all. A nightclub should create a space that is totally detached from the everyday, and which helps people escape. It shouldn’t matter so much where someone is dancing. A great experience on the dancefloor is such a universal happening that the location doesn’t matter at all.

What are the main differences in approach between adapting a ‘found’ space and building a nightclub from scratch?

SA: I’ve worked on a lot of ‘found’ spaces across my 20 years curating events. The key to a ‘found’ space is not to change it drastically, but to amplify what is already there. The audience is coming to find the space for themselves, and they want it in its rawest form. Make it safe for the audience, but then leave it alone.

RB: Context is key. Beirut has a very rich history. It is a city that’s been destroyed and rebuilt seven times. Every spot in the city has a tale to tell; every space, every land has a memory. Ahm was built from scratch on reclaimed land on the waterfront and its architecture reflects our seafaring ancestors. Off & On, on the other hand, is on the ground floor of an existing building located in the middle of expensive downtown Beirut, and reflects its sophistication and luxury.

How do you avoid nightclub design becoming homogenised or formulaic, with every nightclub of a similar size around the world looking the same?

SA: We only work in ‘found’ spaces that served another purpose in a previous life. Our next venue, opening in Spring 2019, is a totally different space aesthetically to Printworks.

RB: Again, context plays a big role. It’s always the starting point and it’s where I draw my inspiration. I place and study every project within its context. There are many factors that contribute to nightclub design. Beirut is not Ibiza or Las Vegas, and what works there may not survive in Beirut.

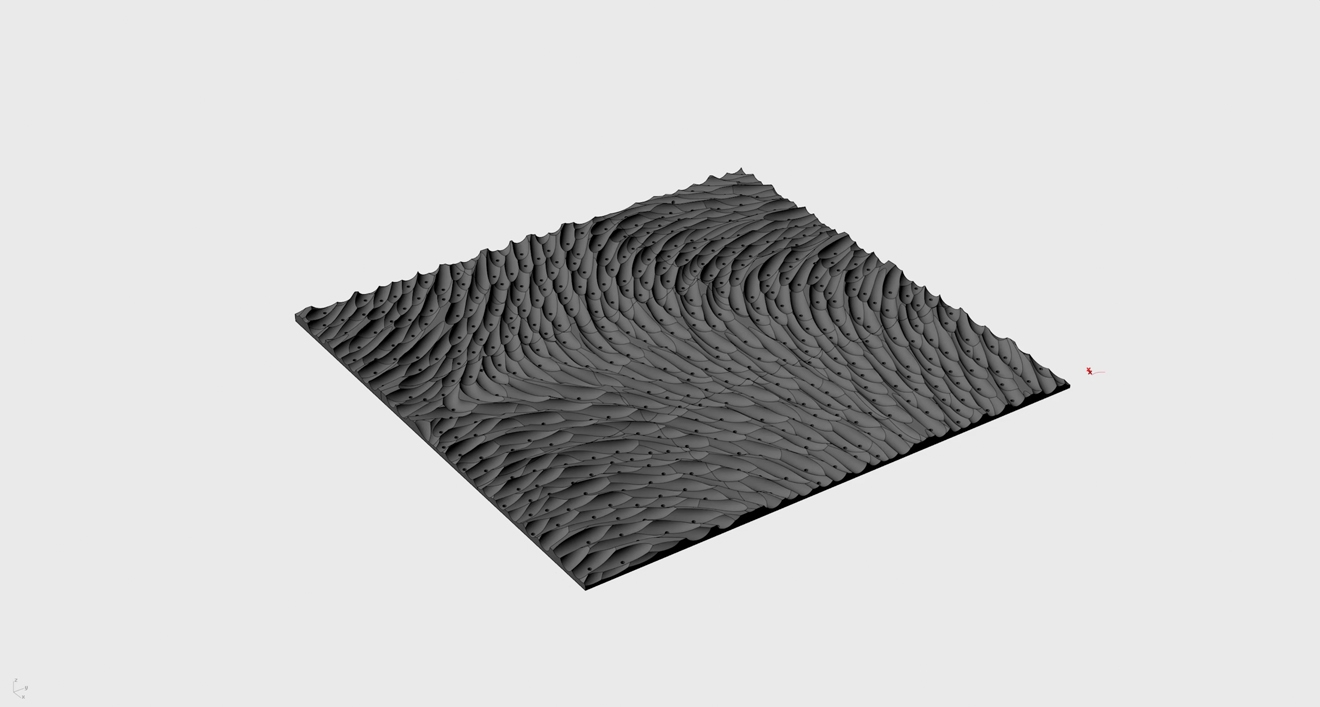

DM: I guess the physical appearance of a good club hasn’t changed so much in recent decades. There’s the dancefloor, the booth and the bar. I’m simplifying a bit, but nevertheless, this is what its all about in the end. Creating the very best out of these three major elements is the tricky part. Establishing a distinct concept and vision, making use of different interior design, the materials (though wood is essential in creating good acoustic spaces) and establishing an aesthetic language for every project. Think of a 12” record sleeve: you’ll always have the outer and inner sleeves as well as the labels. But this recurring structure also serves as a blank canvas for artistic freedom.

How much consideration do you, as designers, give to the DJs’ experience of the club vs the audience’s?

SA: It’s important that the artist loves the venue for them to really make a success of their performance. From my experience of artists from all backgrounds, their focus is the audience enjoying their output. The artist needs to have the best equipment possible and feel totally in control of their space on stage. After that, our whole team’s focus is always audience experience.

RB: I try to make audience and DJ share the experience. In Ahm, the DJ is the bow of the boat surrounded by all the other masts converging towards them. In Uberhaus both the club-goers and the DJ are in the belly of the whale. They see and feel the same experience, but live it differently.

DM: I believe separating these two things is a huge mistake. The experience in a club is entirely different from a festival. In a club, the DJ has to be part of the greater experience, not separated from it. That’s one of the reasons that the booths I’ve built were always positioned within the dancefloor and not detached from it. If the DJ has the best possible working environment at their disposal, is situated within the crowd and everyone shares the same sonic experiences, the chance to create a magic moment is way higher.

Given the big problems of sexual harassment in the industry, how can nightclub design help female or trans clubbers feel and be safer?

RB: Working with a team of 10 amazing women means I am constantly aware of and concerned with issues surrounding safety. My starting point is to create free-flowing movement within the club, and to avoid dark spots, hidden corners, and any places concealed from view – be it from the security staff or cameras. And whenever possible I completely separate the men’s and women’s WCs.

DM: I’m not sure how far space design really has an effect on these very important issues. It is quite clear that creating a safe space for all kind of people is one of the major purposes of a dance music club. Historically, nightclubs emerged out of the need of underprivileged people to feel safe. Nonetheless, I believe creating a safe space is mainly established by club politics, such as a clear positioning within a distinct value system and addressing these issued through all communication channels and managing to constantly establishing a crowd that stands in for these core values and that regulates itself. There are many ways to do that, and I’m not sure in how far mere space design has a real impact on these issues.

What are the single biggest changes in nightclub design since the 1970s, when discos in NYC set the template for ‘the disco’, and what are the main reasons behind these changes?

SA: I can only talk about my basic view, which is that audiences are more driven to purchase tickets if they appreciate the talent on offer, rather than to meet friends or a potential partner at the venue. They come to experience the artist accompanied by incredible sound, lighting, and production, rather than the people on the dancefloor with them.

RB: Clubs have always been immersive environments with intense experiences. The rise of disco in the 70s meant that club culture gained a new momentum, but I believe that since the beginning of the 21st century, clubs have grown more complex. Nightclub design has evolved smoothly, with few major changes.

DM: The major change has been a huge decrease in attention to acoustic space design. That was one of the most important issues for the early temples of dance music like The Loft or Paradise Garage. But these days I rarely visit clubs where I feel enough attention has been given to this issue, though it’s one of the most essential aspects. I don’t really know or understand what the reasons for these changes are, especially since the past delivers such a fine blueprint to build on. I guess maximising profit above everything else may be one of the main reasons.

Designers of the early discotheques sought to create a space for clubbers to ‘express their sexuality’. Is that still something that designers aspire to, or is it an old-fashioned idea?

SA: I don’t believe it’s a primary focus nowadays. We have a much more holistic human experience in mind when curating our nights. I’m sure people still come to meet and build new relationships at our venue, but that’s not discussed in our creative sessions. We talk mostly about music.

RB: Nightclubs are an experimental theatre and the dancefloor is a stage for individual and collective performances, a place where everyone becomes the hero of their own story.

DM: Clubs should be a safe space. Unfortunately, we still live in times in which some people who express their sexuality openly suffer from harassment and prosecution. So I don’t believe that this idea is old-fashioned at all.

The ‘Vegasification’ of club design sought to maximise the commercial potential of nightclub spaces by increasing the space given over to bottle service and VIP areas – even leading to a situation where DJs were booked on how many drinks their music ‘sold’. Have you ever come under these pressures? What were/are the implications of this for designers?

SA: There are definitely commercial pressures that come with managing and maintaining such a big space, but we genuinely don’t do our maths like that. We want to ensure people can get a drink in a timely manner and ensure there is a full range on offer, but our curation policy is not connected to our food and beverage offering.

RB: Beirut is still spared from the mega nightclub chain brands – it’s not Vegas or Ibiza – so we’re never put under such pressure. Of course the pattern is the same everywhere with bottle service, VIP areas, and backstage lounges being an important physical aspect of the nightclub. But in all our designs we give the dancefloor a sizeable space. We haven’t been ‘Vegasified’ just yet!

DM: I’m very lucky never to have been pressured by such things, and would stop engaging in nightclub design if I was forced to shift my focus. I guess you can’t compare (and I say this without being judgmental at all) highly commercial entertainment facilities with traditional dance music clubs.

For more on the evolution of club design, check out the Vitra Design Museum’s ‘Night Fever’ exhibition: www.design-museum.de

The team behind Printworks are launching a new space in Summer 2019. For more information head here.

Duncan Dick is Mixmag's Editor, follow him on Twitter