Features

Features

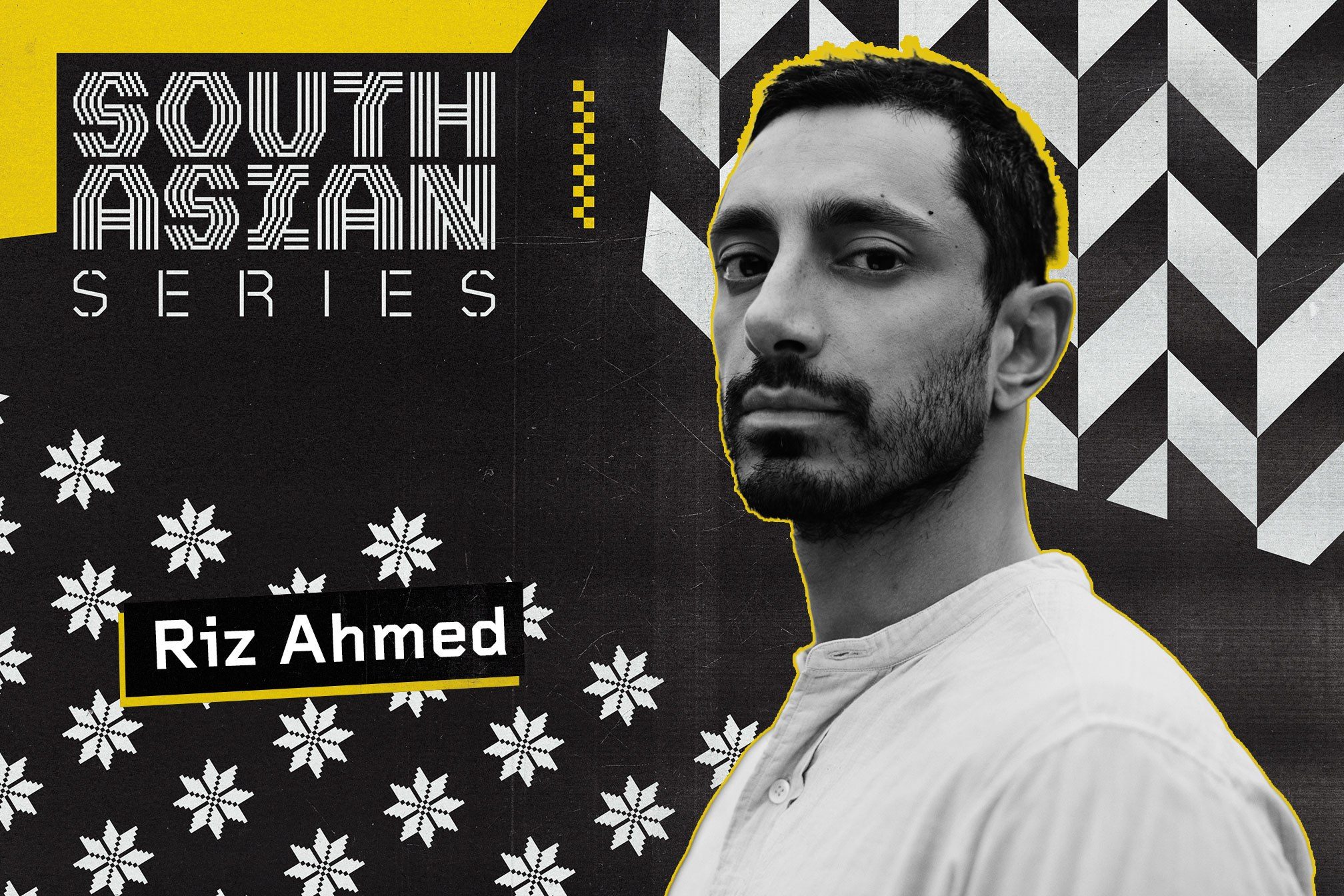

Riz Ahmed: “Home is a place that we're creating through our art”

Nabihah Iqbal talks to actor and musician Riz Ahmed about growing up in London, ‘90s daytime rave culture and fighting Muslim stereotypes

Among the cacophony of voices platformed in the Western media, the perspectives of Muslim people are rarely given the space to be heard. Two crucial figures in the UK who are working to change that are actor and musician Riz Ahmed, who has campaigned tirelessly against the “toxic portrayals” of Muslims in media and this year became the first Muslim to be Oscar-nominated for Best Actor for his standout role in Sound of Metal, and Sadiq Khan, who has been the Mayor of London since first elected to the office in May, 2016.

When approached to guest edit Mixmag’s South Asian Series, I wanted to speak to these two born-and-bred Londoners to share their experiences of growing up in the city, learn about their relationship with its music and culture, and discuss how their upbringing has informed their work and fight against prevailing stereotypes of Muslims in the UK.

First up, read my conversation with Riz Ahmed below, and read the interview with Sadiq Khan here.

Read this next: Sadiq Khan: “Music crosses barriers of race, religion, class and postcode like nothing else can”

Nabihah: As a starting point, could you say a little bit about where you grew up, what part of London, and what your childhood memories are — music related or non-music related? Just set the scene for us or for people who don't know.

Riz: I grew up really in the '90s. I was eight-years-old in 1990 — there was an Asian Underground going back into the '80s. I was talking with Nerm from Shiva Soundsystem, who's like still one of the consistent godfathers and instigators of Asian Underground music for the best part of 30 years now, and he was saying that what we're seeing now is almost fourth wave. We had the '80s thing, there was the '90s thing, there was the early 2000s stuff. There was Talvin [Singh] and Nitin [Sawhney], Asian Dub Foundation, it went away for a while and now it's back. This culture keeps reinventing itself.

Back then, in the early '90s I was growing up on a lot of Bollywood mix cassettes. So on Ealing Road, near where I grew up, you'd go down there to the paan store and the cassette store, and you'd go there for a couple of reasons. One, maybe to buy your aunt or your uncle or maybe your parents some paan. Secondly to get the latest mix cassettes and that's where you'd find the Bally Jagpal or Bally Sagoo or Smith & Jones, these kind of bedroom producers who would take Bollywood hits and put hip hop beats or house beats underneath them. The Love to Love mixtape series, stuff like that.

In the mid-to-late '90s, I'm a teenager and there's a lot of Asian daytime raves going on. The daytime raves are there for a couple of reasons, in the same way that Black London in the '80s was turning to warehouses because they were often turned away from doors in nightclubs. Brown London had that as well, and there was also this internal obstacle of, frankly, Asian girls not being allowed out at night a lot of the time because of the traditional conservative values they had in their house. Daytimer parties were a way of getting around the issues of not being let into other people's clubs, sometimes the West End, but also having our own music, and also making sure that parties were happening in the daytime so that girls could come out. That's really where I caught that very unique British Asian cocktail of garage mixed with Bhangra, turned into speed bhangra, and the Panjabi MC tune first coming out, and even some of them AR Rahman tunes getting played as he was discovering synths. It was those daytime raves, it was about jungle, it was about UK Apache, it was about Metz 'n' Trix and Bally Jagpal.

Read this next: A potted history of the 1990s British (South) Asian Underground

I remember going to this one daytimer in Tottenham and snuck backstage and Bally Jagpal was there backstage with his crew. I must've been about 15 and I’d started rapping, and he overheard me trying to show off to some girls rapping backstage. Afterwards I was like ‘oh shit, the guy who's backstage area has caught us’. I thought we were gonna get in trouble and get thrown out. He was like, "what are you doing here?", I was like "Oh nothing, just this and this", and he stopped me and said: "Never ever sell yourself short. You're talented, do something with this." And he gave me the number of a producer called Rishi. I called that number once and it was off; I was too shy to call it again. That ended up being Rishi Rich. He was looking for a vocalist and a rapper, and ended up finding Jay Sean, which worked out much better for them! They were doing their thing.

I hope that paints a bit of a picture of what was going on at that time, it was a mix of jungle, garage, Bhangra, hip hop, Bollywood. and those daytimer parties were kind of the epicentre of it, people would catch buses in from Manchester, Birmingham, South London, East London, North London. There was a very particular fashion as well, with the really bright coloured clothes, the bright Ben Sherman shirts, the off-key Moschino print was massive. That was also a time in the mid-90s of the peak of the Muslim and Sikh gang wars in West London, Luton, places like that. It was interesting because some of that South Asian politics had spilled out onto the streets, so what was happening with the Khalistan movement and the battle for a free Sikh homeland in India was being funded and represented somewhere on the streets with gangs like Shere Punjab in Southall. And there was also a kind of uniform that went with that, you know, we'd all wear Reebok Classics, but if you were Pakistani, you might wear the green and white Reebok Classics, and if you were Sikh, you'd wear the orange and black Reebok Classics. You’d all wear Adidas Firebird tracksuits, but it might be the green and white or the orange one. Then there were the haircuts with the moon and star or the Khanda symbol shaved into the back of the head, the jewellery with those symbols as well; it was just its own vibrant culture. It was so specific, so unique, so creative, so "fuck you - we're here, we're not going anywhere." And in a way, all of that kind of imploded with 9/11. What that did to Brownness, how it divided Brownness, how it politicised it.

I think we will come on to talking about 9/11 as a sort of watershed moment for sure, but just whilst we're on the topic of daytimers raves - it's amazing to hear about your memories and also how you link those memories of music events to the fashion and everything people were wearing. I remember one time when you were talking about code-switching, and with going out to these parties, you'd have a specific persona or look, but that would not be the same as when you got back home, it would be a totally different look. So at that time when you were going out to these parties - did your parents have any idea of it or did you keep the two things separate?

No, they had no idea. A big part of, I'd say, that British Asian experience of the '90s is having parents from another time and another place. There's that cultural gap, that generational gap. To some extent, they can't give you advice on how to navigate your day-to-day life, the pressures and the expectations of life here in the West. And that meant that your siblings became your parents, and your elders and your cousins became your guardians in a way. My parents didn't know, and I'd say that added a whole layer of sexiness to the whole thing: everything was a secret, everything was held down. There was a kind of innocence to it as well, particularly when its like - and this is pre-mobile phones as well - you meet a girl at a daytimer, go in and talk to them, you can't talk to them from your home, you can't just call up their house and their mum and dad picks up the phone, "Hello, can I speak to Anita please?" — that ain't happening! You've gotta sneak out to the phone box, you've gotta hit them on their pager, they hit you on your pager, you've gotta press 1471 before you dial which means that the number is withheld, you know.

Read this next: What Do Your Parents Think?: 4 South Asian DJs share their family's reception to a music career

There was a romance and a danger to the whole thing. Because your parents could not understand and were from traditional families, and it’s not like: ‘oh, what so your parents will get upset with you’. It's a different time man. You hear all the time about people being sent back to Pakistan, people, often sadly girls, being sent to Pakistan, people getting married off. That was the reality. I'm not trying to perpetuate any stereotypes, but things were at stake, you know? And if it wasn't that, then it was your izzat [an Urdu word translating as ‘reputation’ or ‘honour’]. And that's meaningful. And for a community that might not have a lot in savings or a lot materially, in a way your life savings is your izzat. So to squander your parents' life savings, it meant something. I would say that the secret element, the cloaks and daggers of it all, added a danger, but a kind of romance to it.

What you were talking about was probably reflected in the wider British Pakistani community that was in London at the same time as you. It just seemed like it was a collective experience, rebelling against — not even rebelling, but just being who you wanna be and doing what you wanna do — but then having to face this very strong structure that comes with your family and the wider sense of what it means to be Pakistani, what it means to be Muslim.

Yeah. I wouldn't say it's as clean cut as: this is who I wanna be and this is what I wanna do. I think you're conflicted in every place, you're conflicted in every role. You're out there in the daytime, you're doing this, that and the other, but you're also going to the mosque, you also feel on some weird level: aw, should we be doing... you have those community values but you're also kind of betraying them. It wasn't as clear cut as that, I'd say, particularly then. Because the one thing you knew was that mainstream society didn't have a place for us, wouldn't make space for us, and so you turn to your own community for your sense of what values are and how you should live and who you should be. But of course, that's also presenting you with a lot of obstacles. So I guess it's like when the community is something you draw strength from, but it's also something holding you back from doing things you wanna do, it puts you in a double consciousness.

Yeah, and I guess that's something that you deal with a lot in Mogul Mowgli, the film. In a dreamlike way, but also in a very real way, this antagonism between the younger generation and the older generation. But I feel like things are changing, what do you think?

Yeah, of course. I mean, I'm talking about what it was like back then, because people might not know. One thing I would say is that there is no uniform experience. I'm talking about stuff I've seen, stuff that I grew up around, my community in a certain place and time. Probably you'll speak to other people and they'll echo that. But you also might speak to some people and they'll say something different. I would say: are things changing now? Maybe, you know, as you have more people assimilating, more people integrating, kids today with parents who were born here, a different set of values, different expectations. There aren't daytimer raves anymore, you don't need them. So of course things are changing on some level. Having said that, whether you go to New Jersey or to Bradford or to Luton, and you find Pakistani communities or South Asian communities there, often some of those values still hold. Openly dating, you've got to hold it down.

It varies from family to family, really.

Absolutely, yeah. I'd say it varies from family to family, and I do think class comes into it. And: where are you kind of able to stack your chips? I think if people have a stake in mainstream society, they're more open to taking some of those mainstream values. If they don't, I think then: why would you do the currency conversion if you're not gonna end up with anything? You're gonna stack your currency in your community, in your values.

Read this next: How daytime raves introduced clubbing to a generation of young British South Asians

Yeah, exactly. Over the last 10 years or so, there's been so many important people coming out of their community, and you're one of them. You're kind of breaking the mould, just setting a new standard and opening eyes. It's like what you were saying earlier about 9/11 being a changing moment for how people are viewed, and what they symbolise. I want to talk to you about that because you are a male, Muslim, Pakistani guy, born and brought up in Britain. What did 9/11 feel like to you and the shift after that? I know you've dealt with this in Four Lions in a really poignant way, but speaking now in 2021, how has it been?

You know, it's weird because I still don't think we have had the proper distance from the post-9/11 era, which I hope is now onto a close finally. Or maybe that's wishful thinking. I think we don't have the distance to fully understand the effect it had or not, and our sense of selves and our sense of each other. I think it's been profound, I think we've all been going through a collective trauma. You know, we've all been told implicitly and explicitly that we have to pick a side: you're either with us or with them. It's either East or it’s West. And people were forced into these binaries, people were, I feel, forced to distill their complex identities into these simplistic boxes. By that, I mean... I just remember so many guys I knew, people, DJs, suddenly breaking or selling their records and becoming super religious. I remember that. I remember how the Asian scene just fractured. Also, with the kind of class ascent of the British Indian population compared to the British Pakistani and British Bangladeshi populations. So our experiences are different, it's hard to generalise, but the stats tell you a very clear story.

There are different experiences, and particularly with the criminalisation of those Muslim Asians. The demonisation and the policing, it becomes different experiences. So that whole thing kind of fractured. Post-9/11 we became Muslims. We stopped being British Asians and we became British Muslims. The way I see it, in the '80s we were Black, in the era of political Blackness. And in the '90s, we became "p*kis". That was what people called us or what we called each other with pride. And then post-9/11 we suddenly became Muslim.

In a way, navigating that shifting identity — not necessarily because of anything you've chosen, but because it’s happened, circumstances outside of your life have shifted — you kind of run to meet the challenge by rebranding yourself as a Muslim not an Asian, or an Asian not Black. So much of my work has been about the post-9/11 blues, or so much of my music, or Four Lions or Reluctant Fundamentalist. So much of my work has been in some ways a response to the dominant narrative, to try to subvert it or overturn it.

What's the importance to you of having that as your outlet, especially music as well. If you didn't have the music to try and subvert all of these things, where do you think the power is?

Well, I've made a decision to not take acting roles that feed into those stereotypes. I think films like Four Lions or Reluctant Fundamentalist - that stuff also subverts the narrative, you know? But the music for me is... it's just me. When you have to spend so much of your life as a British Asian, and I'd say even more as a British Asian now, code-switching, you know, still to this day. You have to leave part of yourself at the door in order to enter a room often. Your Pakistani side, your British side, your posh side, your street side, your rapper side, your actor side. For me, the music is a place where I can bring it all to the table and just be all of myself. And that's represented in the beats, in the music, in the lyrics, in the use of languages. In a way, Mogul Mowgli takes that even a step further, where it’s the acting and the rapping in Urdu and English and all of it together.

Read this next: What it's like to go clubbing as a British South Asian person

Something I've been thinking about more and more is actually not responding to their narratives, not making work as a reaction, not trying to go and enter rooms that we're not wanted in. I always thought it’s about stretching the flag, kicking down the door, the place where you don't belong is a place where you should be and you can stretch it and add something new. And I'm thinking, you know what? That is important, we've gotta do that, I've done some of that, loads of people are still doing that. But something I'm really interested in is like: let's go make our own room. It's not about separatism, it's just about taking pride in the place you're already from rather than always looking to the place that you wanna arrive at, and dreaming about arriving at a place of being accepted by others. Let's start with actually accepting ourselves, our home, where we're from. And that's what Mogul Mowgli is an attempt to do, it’s a kind of homecoming, it's like: I'm not gonna play another role, I'm not gonna represent anyone else or for anyone else, I'm just gonna present myself. So, I think we've seen a shift and I hope we continue to see a shift in us being forced to respond to their narratives and add complexity to them, to actually just telling our own stories.

I think that's how to view it. You've put it really well and succinctly, you've gotta make your own space. I just want to ask you one more thing: based on how you were just talking about music and describing your music as a space where you can do what you want and it acting as a factor of bringing people together, the people you want: I think that could be a metaphor for how I view London as well. London has a charm in itself of being the biggest and probably best multi-cultural city in the world. So I wanted to ask you about what's your specific relationship with this city and how you feel about being a Londoner, and how has the city shaped you as a person — against the backdrop of all these things, being who you are and off the back of 9/11 and the prevailing stereotypes?

I feel like you can't see the true face of London, you can hear it. You have to listen to it, you know. London, and I'd say the UK, the real pulse of it is something you listen to, you can't see. And it's music, it's in that bedrock of Jamaican and Afro-Caribbean soundsystem culture being interlaced with European, American house music and being mashed up with Indian and Pakistani folk music and qawwali and grime and drill, taking that and mixing it. It's just a testament to the UK's endless creativity on a street level, and the endless creativity and possibility of multiculturalism. That is something that's proven time and again through the musical output of this country. Look at ska, or whatever. I feel like, to me, to be staying close to music in London, to continue to make music that's inspired by this city, keeps me close to myself and where I'm from. And that's why in that rap 'Where You From' and in Mogul Mowgli, it's almost like: maybe the place where you belong isn't a place that I can touch, isn't a place where I can build a house. When I think about what's the neighbourhood that someone like me really belongs in? I sometimes now, still, struggle to think where that might be. The world can still be these ready-made boxes that a lot of us don't fully seem to belong in at times. But maybe the place where we belong is a place that we're creating through our art. Maybe it's a place that we're creating through our music. In those lines, in those lyrics, in those beats, at that rave, that's the place I belong in. And so I kind of feel like home isn't a place that you'll ever find, it's a place that we're creating through our art. And to me, that's what's always been the central mission and message of the Asian Underground. It's about taking this cultural hybridity and finding a place for it to live and thrive, 'cos the world still ain't ready for it. So we've gotta make that home for it.

That is such a poetic way to put it. It sums up everything and I totally agree. I've never thought about it that way but you're totally right, it's just making your own space and maybe that is something intangible, but it’s there and you can feel it nonetheless.

We'll feel it at Dialled In festival, I'll see you there.

Nabihah Iqbal is DJ, producer, musician and broadcaster and the guest editor of Mixmag's South Asian Series, follow her on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook