Features

Features

How daytime raves introduced clubbing to a generation of young British South Asians

Safi Bugel explores the history of daytime rave culture and its seismic impact on British South Asian youths in the 1980s and '90s

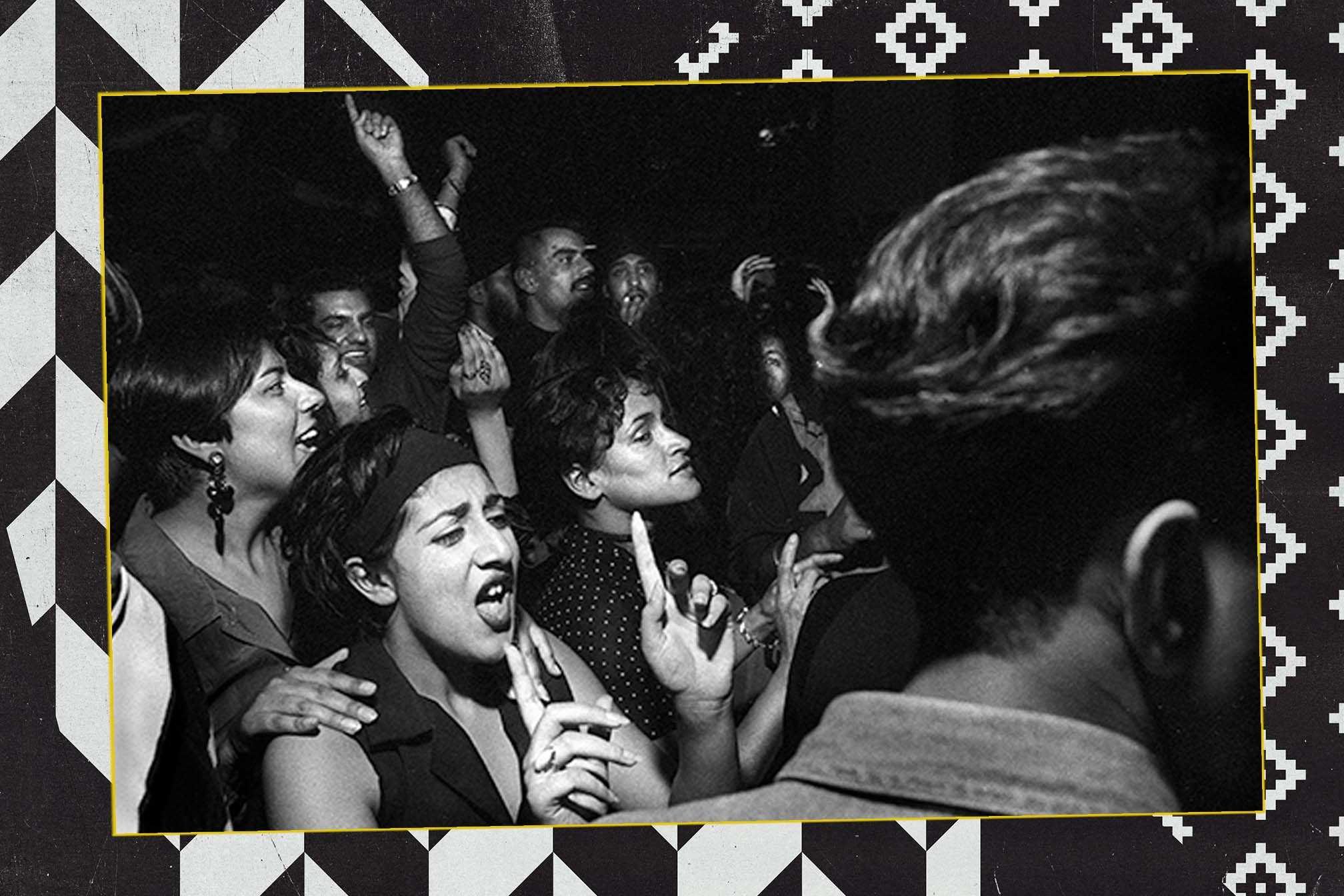

Restricted by their parents’ expectations yet fuelled by a desire to let loose, British Asian kids worked around a hostile and predominantly white club circuit to forge their own scene in the 1980s and ‘90s, operating in the afternoons and at local venues. Taking place across the UK from London to Bradford, these daytime parties were avenues for young people of South Asian descent to dance, drink or even hook up — set to the soundtrack of their own music and on their own terms.

“I wasn’t allowed out much as a young person,” says Sarah Sayeed, a British Bangladeshi musician who came of age during the ‘90s. Sarah was just 15 years old when she began skipping school to catch the daytime raves at Hammersmith Palais— a self-proclaimed act of rebellion while living at her family home. Indifferent to drinking alcohol or catching the attention of boys, she was instead preoccupied by the tunes being played by the DJs and live bands. “I loved music and wanted to experience it how I imagined it would be best experienced,” she says: “in a club!”

Read this next: What it's like to go clubbing as a British South Asian person

Hearing a mix of R&B, Bhangra and d’n’b in these settings was not only a chance for Sarah to dance, it was also formative for her own career as an artist. “It was mega,” she says, recalling the thrill of being plunged into erupting dancefloors. “The parties were part of my journey in that they were the earliest part of my life in music and clubs, hearing MCs and influencing my own path as an MC and musician.”

The same can be said for DJ and radio host Bobby Friction, whose deep-rooted passion for music emerged from the afternoon affairs he attended almost a decade earlier. Initially enticed by the hype, girls and drama on everyone’s lips, Bobby would turn up to his local Hounslow parties “en masse”, accompanied by a group of 15 people. Though the sounds of Bhangra didn’t align with his tastes at the time, the combination of soundsystems, live bands and audience “frenzy” made an impact. “For the first time, I discovered the glory of live music, the glory of communal musical worship,” he gushes over the phone. “I then transferred that to everything else in my life… everything I live for now got picked up during those first few gigs.”

Meanwhile, the wave of daytime parties was also sweeping over the Midlands. Like Sarah, Manjit, who grew up in the region, did not drink at the events she went to in the early ‘90s. But just being in these settings felt liberating as a teenage girl from a traditional Sikh background. Joined by college friends, Manjit would secretly hop on trains between Birmingham and Leicester twice a month to catch the live Bhangra sets. “It was purely for the love of music,” she reminisces.

While the rules for girls tended to be tighter than those enforced on their male counterparts, young Asian women were still very much a part of these spaces; Manjit recites stories of girls glamming up in the toilets, before dressing down at the end of the event to return home for dinner. For those from strict families, it was a glimpse of an alternative lifestyle.

“For me, life was pretty much laid out,” she explains. “You go to school, go to college. If you’re lucky you’ll be allowed to go to university, if not, you’re gonna get married off and here’s who you’re gonna marry.”

“In that respect, I saw [the parties] as an opportunity to let off some steam, enjoy Bhangra music and go a little bit wild,” Manjit continues. “Essentially I knew that I would end up in an arranged marriage situation and that would be the end of it.”

Read this next: What Do Your Parents Think?: 4 South Asian DJs share their family's reception to a music career

Indeed, Manjit’s marriage around the time of her 19th birthday marked the end of her stint in the daytime party scene. “I was hardly going to be going to daytimers, being the respectful daughter in law and all that,” she says with a sardonic laugh.

Despite this endpoint, the friendships and memories Manjit cultivated across those afternoons remain intact. “I’m still connected with a lot of my college friends from Leicester and we often talk about [the parties]. Obviously we’re a lot older now, we’ve got our own families, kids and what not, but we talk about our daytime years: the fun we used to have and the jokes we used to pull on each other.”

This sense of connection and belonging was shared by many young British Asians in attendance. Mayank Joshi, a British Gujarati activist, entered the scene at 13 and found solace in being surrounded by a network of Brown people his own age.

“In my class at secondary school, there was about five or six people of Indian origin,” he recalls,“we didn't feel so comfortable going to parties which were predominantly white.” Instead, Mayank and his friends headed to the day events his South Asian peers were running in North London. Here, unlike elsewhere, they were not overlooked or profiled.

Read this next: A potted history of the 1990s British (South) Asian Underground

“It was just nice seeing this space of Brown people doing thethings that all the white people were doing to have fun,” Mayank smiles, recalling the rush to get tickets and the vodka lemonades he’d drink to limit the smell of alcohol from his parents. “And then there was the unique Bhangra music which we didn't get anywhere else. This made it our very own unique space.”

However, like many, Mayank’s experiences at the day parties were not all positive. With the fun and intoxication came clique mentalities, toxic masculinity and intercultural hierarchies. It was not rare for the teenage antagonism within these spaces to break out into physical or verbal fights.

“It was very much a case of the good, the bad and the ugly,” Mayank says. “You had to be bold or beautiful to be in the hierarchy of the situations. For everyone else, you could feel quite excluded.” At 19, he left the parties for good.

As interests changed, cultural standards shifted and nightclubs became more accessible, the daytime parties fizzled out towards the turn of the century. The legacy of a boundary-breaking scene that spanned two decades has left an indelible mark on the history of music, youth culture and diaspora in Britain.

Safi Bugel is Mixmag's Digital Intern, follow her on Twitter