Cover stars

Cover stars

The unstoppable rise of Michael Bibi

Perseverance, tenacity and tireless hard work are behind Michael Bibi’s ‘overnight’ success. But the hottest property in DJing says he’s happy just to be accepted

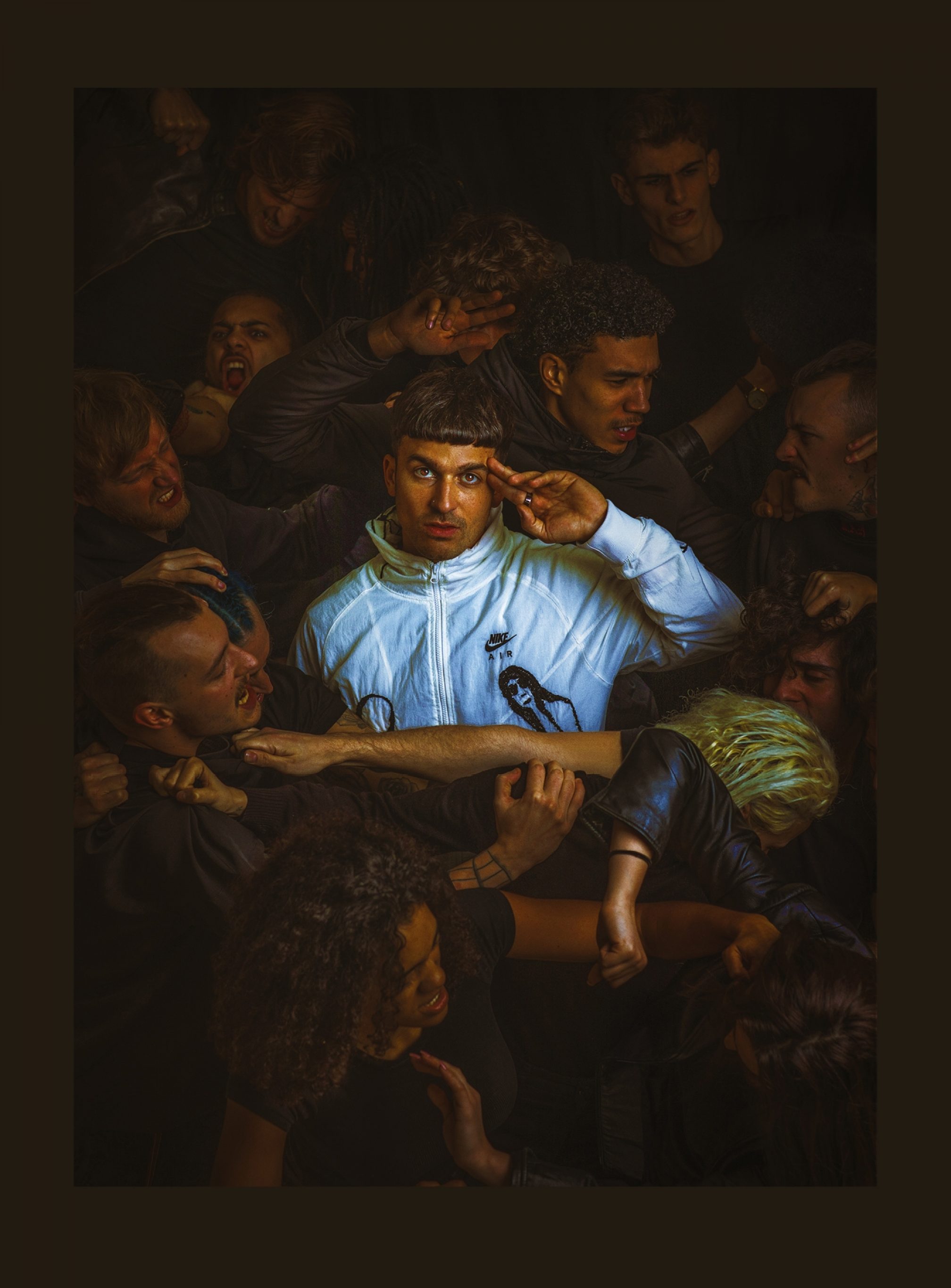

He’s just arrived in Manchester to play a sold-out solo show at The Warehouse Project, but Michael Bibi’s mind is on another, earlier gig in this city. Was it last March, when he performed at Joshua Brooks as part of his solo tour? “It’s not that one,” he tells us, his tanned, youthful face framed by a blunt fringe of dark hair. The event sticking out in his memory was in December 2016, at small basement club Stage & Radio, during a time when Bibi’s club night Solid Grooves was already filling out 1,500-capacity London venues. Manchester was Bibi’s first booking outside the capital. “I’d planned it for ages, and I thought it was going to be amazing,” he says, taking off his coat, revealing an all-black outfit of cargo pants and Balenciaga hoodie. “I turned up and there was, like, ten people. Maximum. It was a real quick, sobering, smack in the face – ‘Nah mate, there’s a lot more to do here’,” he says, leaning back on the sofa in his hotel room.

Bibi might appear to have come out of nowhere, fully formed, when in October 2019 he singlehandedly sold out the 3,000-capacity London venue Magazine, but a lot happened between that career-defining moment and the disappointing first Manchester show. After six years running club night-cum-record label Solid Grooves, in the summer of 2018 Bibi made ‘Hanging Tree’, a hypnotic track whose sample he came across while watching The Hunger Games at the cinema. Focused as he was on the other artists on his label, working 18-hour days to make the imprint a success, he forgot about the song and only remembered it three years later, when a remix he was working on reminded him of the vocal. He made the track in 45 minutes, played it out that night at Egg London and it instantly went viral, starting a series of events that catapulted Bibi to superstar DJ status – selling out London’s Leake Street Tunnel in 15 seconds, winning Best Tech House DJ at the 2019 DJ Awards, and running the hugely successful Solid Grooves residency at Privilege Ibiza.

Does he feel famous now? “I feel accepted,” Bibi replies in a London accent softened by constant travelling. At the time of our meeting he’s been on the road for six weeks, and is unlikely to slow down any time soon – this summer (prior to the COVID-19 outbreak) he was booked to play the Amnesia Opening Party with Jamie Jones, Adam Beyer and The Black Madonna, head up the Solid Grooves stage at Offweek Festival in Barcelona and return to Manchester for Parklife, among countless other shows. “I never felt accepted by the music industry until very recently,” he says, describing how, after a three-year electrical engineering course reluctantly completed on the advice of his father, he left London’s rave scene where he’d fallen in love with drum ’n’ bass and True Playaz nights at Fabric, and went travelling in south-east Asia. It was during this one-year break that he decided to become a DJ, after getting into minimal house. But, on his return to London, reality hit home: he didn’t know anyone in the industry. Knocking on doors to get gigs, he was rejected from venues around Brixton before finally convincing Jamm to give him a chance. He filled the club thanks to his friends from the rave scene and what would become his trademark: long hours and tireless promotion. He was rejected again as he turned to producing in 2014. “It was the same thing again: ‘No, no, who are you, this music’s weird’” – though, charitably, he won’t mention any labels by name. He persevered, he says, because “When I’ve got an idea in my head that I want to do something I hold onto it tenaciously; I never let go of it, so I was like, ‘I’m not going to give up on this.’”

Read this next: 8 acts who defined 2019

Michael’s desire to be accepted dates back to before his music career. “The first few years of secondary school I was quite awkward and I wasn’t fitting in,” he admits, silver rings and necklace catching the light as he shrugs. “But then I found that putting together mixes – I used to do mixtapes and just give them out – doing stuff like that was a way that I could relate to other people.” His awareness of how music can change people’s perception of you came a few years prior, when Bibi was 10 years old, living with his parents in Wimbledon and learning to play guitar. “I had to do a Grade One classical music piece and I got 100 per cent,” he recalls. “It’s unheard of at that age, and I remember a really distinctive feeling of getting respect, or admiration: people knowing who I was because of the fact I’d done that.” He pulls on the drawstring of his hoodie to add a shy kind of emphasis. A slight social awkwardness surfaces occasionally – a break in eye contact, a fiddle with his clothes or a slight shift in body language from his generally confident manner, expressive gestures and easy warmth. It’s a reminder of his childhood legacy as an outsider.

Being musical was in Bibi’s genes. His father is blues guitarist Robin Bibi, who’s played with the likes of Robert Plant and Ben E King, and his mother is a dance teacher. His younger brother has a talent for music as well, but he decided to become a chef. “My brother always took more after my mum and I took more after my dad,” Bibi says. And while his parents weren’t initially best pleased when he got into electronic music ( “pots and pans”, his dad calls it) it was his father’s blues records – via an eclectic range of influences from Skream and Benga through to Felix da Housecat, Jamie Jones and Lee Foss – that eventually came to inform Bibi’s sound. “A lot of the blues songs, they’re really kind of deep. With the lyrics, you hardly understand what they’re saying, but the voice just sounds really sleazy and sloppy and I really liked that,” he says, name-checking Doc Watson and Roscoe Holcomb. “I think a lot of my tracks – ‘Got The Fire,’ ‘Devil’s Candy’ – they’re really slow and lazy, and if you listen to blues tracks, blues singers, it’s a very similar style.”

Read this next: The Cover Mix: Michael Bibi

Sampling is also integral to Bibi’s sound. He’s an ear for the obscure and eerie – haunting vocals such as on his 2019 released ‘Garden Of Groove’. “I sample everything,” he says. “I’ve never really used much hardware in my studio. I’ve only got one Moog Minitaur [a small bass synth] and one Roland TR-8 drum machine which I’ve only really had in the last eight months. Before that it was all software – just me and a laptop.” Indeed, his latest release, a remix of ‘Eyes On Fire’, came about when he had YouTube on in the background and chanced on the Danish band Blue Foundation’s sad guitar-driven pop song; he played it out in his set with the addition of pronounced drum licks and sharp synths. Meanwhile, one of his biggest tracks to date, the odd and ominous ‘Otto’s Chant’, which he made with Skream, samples an infamous scene from The Wolf of Wall Street.

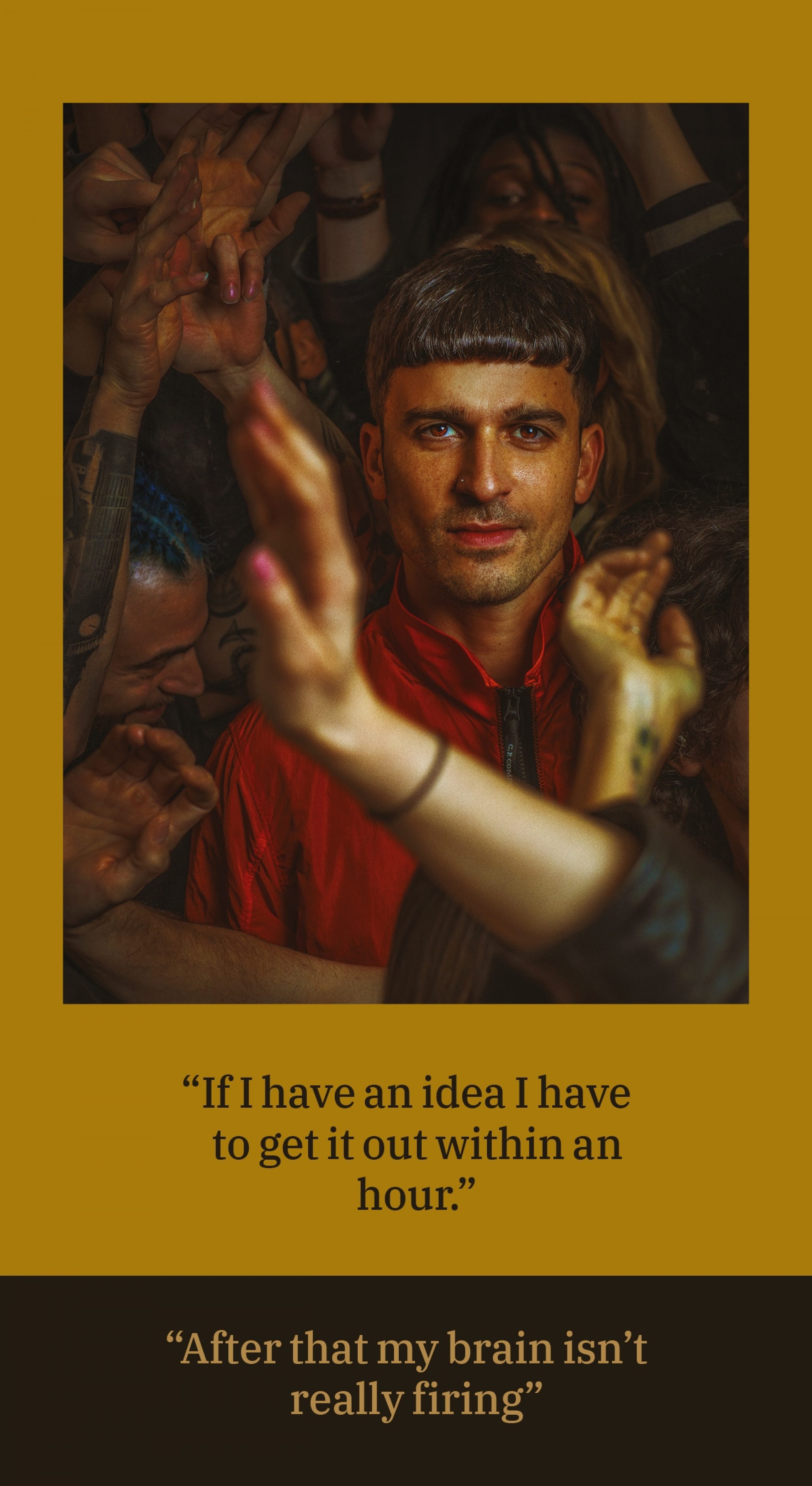

But there are many tracks in Bibi’s back catalogue on which sampling takes a back seat. He describes his creative process as something where speed is of the essence. “If I have an idea I have to get it out within probably, like, an hour, and after that hour my brain isn’t really firing any more,” he says, his method aligning with the fast-paced nature of how music is made and released now. “I’d spend so much time searching for a sample that fitted my track that I’d lose the flow, so I was like, ‘Let me just record my own vocal, just for now’.But what happened was I’d put the recording on, and then I’d think, ‘It sounds alright with just my voice’.” This isn’t to say Bibi isn’t also something of an obsessive, committed to being thorough: “If I’m going to release a track I’ll tweak that track so much, and then I’ll go back to the first version again. I always find that you have to go to that place of trying everything to know that you don’t want any of it. That’s when I feel comfortable.”

Read this next: "Working on the idea for 15 years": How Kölsch made 'Grey'

When it comes to DJing, Bibi’s primarily inspired by his years raving, where he “learned a lot about what works and what doesn’t. and the vibe of what people want.” His signature restrained approach – no massive drops, but a steady BPM punctured by nods to jazz and Latin flavours, while maintaining a commitment to tech-house through tracks made by friends and label signees – is in evidence across mixes such as his Tobacco Dock set, as well as when he plays The Warehouse Project later that night. This distinctive style, coupled with a natural intuitiveness, sits side by side with Bibi’s calculated approach to his career. He says his years promoting – setting an alarm for 3:AM to go flyering outside clubs – informed his bold move to book a solo tour against the advice of his manager, following the success of ‘Hanging Tree’. As he explains, he could take his artist hat off, put his promoter hat on and ask, “How many tickets can Michael Bibi sell in this city?” His commitment to never playing to 10 people again led to a forensic understanding of the level and location of his fandom, which in turn led to a sold-out tour, and even more hype.

Bibi’s passion for long sets of four to five hours was the result of a personal awakening which came at a point when he was unravelling mentally. In the midst of touring and excited by the heights of his new-found success in early 2019, he was saying ‘yes’ to everything: “Every after party, every event, just keeping going, going, going,” he recalls, describing a particularly memorable event in a Leeds’ student house, where he says so many people were packed into the living room that the floor almost caved in. As chaos unfolded around him, Bibi stayed on the decks, playing until midday. A legacy from his childhood – that desire to make friends, to please, to be accepted – was threatening to burn him out. He agrees, but points out his knack for understanding himself better than anyone else does, and says this was what saved him.

Read this next: The Secret DJ on how to avoid burnout

He asked his manager for time off, going to a meditation and yoga retreat in Jamaica – just him, one other person and the yoga teachers, where it was common not to see anyone for 24 hours. “I was at the peak of my career, the point I’d always wanted to get to, but I was probably the most unhappy I’d ever been,” he admits. He completed the programme – juice cleanses, a digital detox and plenty of meditation – but then he got straight back into making music, spending the rest of the trip producing tracks on his laptop, including the June 2019 track ‘Isolate Ctrl’. “I was going right back to the very start when I was making music just for fun, just for love,” he says, smiling at the memory.

Crucially, he also came to realise that for him, meditation informs the purpose of clubbing. “You go to a club with your friends and you leave the club with your friends, but at the peak moment in time when you’re dancing, you’re peaking on your own, and the more you isolate yourself, the more you can enjoy it,” he says, explaining that this realisation inspired Isolate, the club concept he launched on his return: just him, playing all night. A focus and musical unity designed to create a meditative state. “I think a lot of rave culture is being on your phone and stuff. That’s fine, but you need to remember to connect with yourself, and I think you really can learn about yourself via raving.”

We’re keen to see how this concept plays out in a packed club. Certainly, isolating yourself physically is somewhat difficult when a show is sold out at The Warehouse Project’s 10,000-capacity Mayfield venue, on its Concourse stage. Indeed, even before Bibi arrives, the audience is more like a sea of bodies than discernible faces. When he takes to the stage at midnight, there’s an instant atmosphere change, the excitement of the room palpable. “Bibi, Bibi, Bibi,” the clubbers, who’ve come dressed in shorts and T-shirts despite the relentless rain outside, chant as a halo-like sculpture of a circle hangs above: the Isolate logo. Meanwhile, red lasers bathe the steel pillars of the disused railway depot in a warm glow, and the audience’s sunglasses no longer feel out of place.

Read this next: 16 of the best uplifting DJ mixes to get you through self-isolation

Soon Bibi, whose slight build looks somehow more imposing on the stage, arms often outstretched across the three decks – has his audience in a trance-like state. It’s difficult to find a raver whose eyes aren’t glued to the breezeblock stage, situated on ground level in a way that’s reminiscent of theatre in the round. Where Bibi’s idea that club music can be a type of meditation really comes through, though, is when he starts interweaving snippets of songs like fleeting thoughts. Tracks as wide-ranging as Sophie Ellis-Bextor’s ‘Murder On The Dancefloor’, Dizzee Rascal’s ‘I Luv U’ and Gorillaz’s ‘Feel Good Inc’ come and go, teasing but never quite taking over the comforting repetition of the beat. And when Bibi plays his own tracks, he’s the tech-house Billie Eilish, whispering his sad melodies to a disenfranchised Generation Z.

Given the devotion his fans are showing at The Warehouse Project – hands gripping the Perspex barrier between them and the booth, a sea of phones lighting up the room as they film his arrival, and, after he plays his last track to rapturous applause, dozens of fans asking for selfies – we wonder whether he regrets not making ‘Hanging Tree’ sooner, when he first got the idea. “No,” Bibi says, with the assurance of someone who’s given this a lot of thought. “In every artist’s career there’ll be one catalyst which really puts you into the spotlight and pushes you up and everyone’s like, ‘What is this guy about?’ Because it took me such a long time to get that catalyst moment, I think when the spotlight did come and when people started going, ‘What is Michael Bibi about?’ I had a very big back catalogue of tracks.”

That back catalogue, characterised by searching, melancholy vocals harking back to his father’s blues records, is perhaps the reason he’s found such a big audience at this precise moment, the tracks fitting the zeitgeist. But just as importantly, his perseverance and, as a result, the breadth of his experience in every aspect of the industry, also means he was able to execute every step with laser-like precision. Still, as we circle back to the idea of fame, he wavers. “I don’t feel like I’m famous at all,” he says; then pauses again, and concedes that we might be on to something. He recounts a recent afterparty in Argentina where the loudness of the cheers that greeted him gave him goosebumps all over his body. “Yeah, that’s probably the next thing I need to make sure I keep a grip on,” he says.

“I’m still normal, though,” he wants us to know as he warmly hugs us goodbye – a superstar, but a relatable one, who, despite all his success, still seems at times like the shy boy at school trying to make friends.

Kamila Rymajdo is a regular contributor to Mixmag, follow her on Twitter

Read this next: Get the best of Mixmag direct to your Facebook DMs