Features

Features

The incredible story of soul singer Teddy Pendergrass

Teddy Pendergrass was in a near-fatal car crash in 1978, which seemed to end his career. Now a film tells his story.

When asked who invented house music, Chicago legend Marshall Jefferson only half-jokingly replied: “Earl Young’s foot”. For those of you not versed in drummers’ lower limbs, Earl Young was the sticksman behind the powerhouse studio band, MFSB, that recorded countless soul and disco classics emanating from Philadelphia during its glory years in the 1970s: The O’Jays, The Intruders, Harold Melvin & The Bluenotes, Jerry Butler, People’s Choice, The Trammps; the list is almost endless. It was Young’s four-to-the-floor kick-drum rhythm that provided the motor for disco to rise and conquer the world, and when house repeated the trick in the mid-80s, it was no coincidence that Frankie Knuckles described it as “disco’s revenge”.

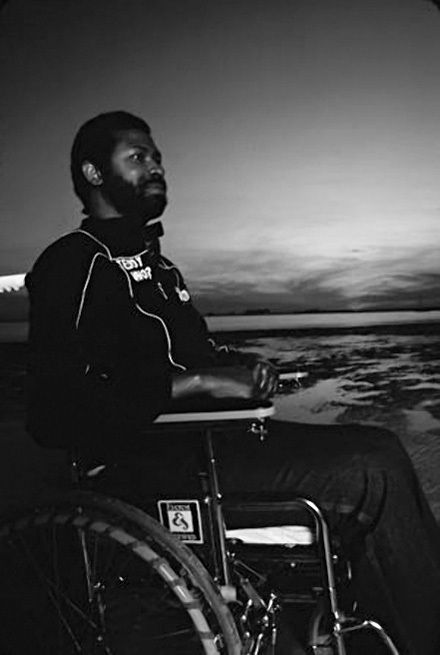

But there was another drummer who made a huge impact on the soul world in Philadelphia – not least when he gave up the drum kit for the microphone and became Philly’s number one sex symbol, thanks to a gruff baritone delivery and smooth stage appearance: Teddy Pendergrass. ‘Ghetto kid makes it big’ is neither new nor original, but what elevates his life above others is what happened next. In 1978, Pendergrass’ manager Taaz Lang was gunned down outside her home. Four years later he was involved in a car crash, when his car careered off the road. He was left in a wheelchair. Eventually, and against all odds, he returned to the recording studio. His comeback album went gold.

This is a story of redemption and renewal from one of soul music’s most compelling – and much-sampled – voices. Alongside The O’Jays’ Eddie Levert, Pendergrass was the most significant voice on Philadelphia International Records, first as the lead vocalist in Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes and then as a solo performer. The two acts delivered countless crossover hits for the label, as Philly International became the most exciting label in US r’n’b during disco’s inexorable rise.

Teddy Pendergrass began his career as the drummer in Harold Melvin’s band before exchanging the drum riser for the microphone, his importance in the band cemented by stellar performances on songs like ‘Wake Up Everybody’, something that eventually caused friction in a band that, confusingly, bore someone else’s name. After scoring a No 1 hit with the first song they ever wrote, The O’Jays’ ‘Back Stabbers’, Gene McFadden and John Whitehead were assigned the task of writing and producing for Harold Melvin. “Working with them was a challenge,” recalled Whitehead, “because most of The Blue Notes couldn’t sing. When we cut a record, me, McFadden, Gamble and Huff would be The Blue Notes. We would sing all the backgrounds in the studio, like a Milli Vanilli kind of a thing. Only Harold and Teddy sang their own parts.”

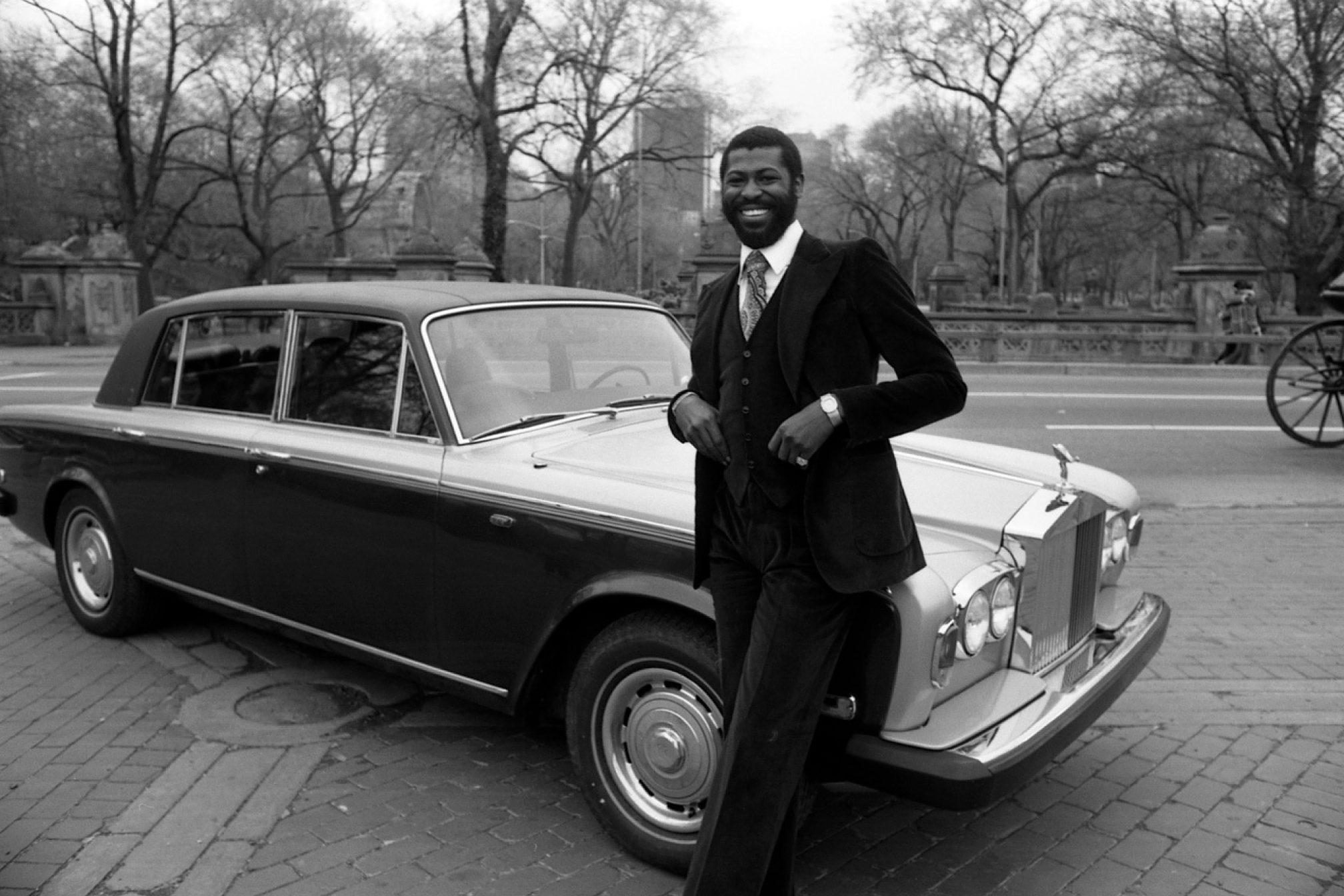

Despite scoring another Top 20 hit with ‘Wake Up Everybody’, Pendergrass was at loggerheads with group leader Melvin, whose financially careless treatment of the rest of the band rankled. Pleas from Gamble and Huff not to upset the winning formula were ignored by an impetuous Teddy, who announced that he was pursuing a solo career. Gamble and Huff then asked Pendergrass if he had an issue with Melvin remaining on Philadelphia International: “Hell yes, it’s either him or me,” Teddy replied. Melvin left and signed to ABC; Pendergrass’ self-titled debut album on Philadelphia International was released in 1977. It was an instant hit.

Over the next five years, Pendergrass established himself as one of the leading lights in American r’n’b, and its number one sex symbol. His appeal was such that alongside his savvy manager Shep Gordon, they began promoting women-only shows (which sold out). Sometimes, however, female fans would go too far. At one show at the Greek Theatre, one left a two-month-old baby in her seat for him; another broke into his house and was found naked in his bed by Teddy’s housekeeper. Not even the ‘Love Walrus’ Barry White or James ‘Sex Machine’ Brown could compete with Pendergrass on the sexytime front.

PHILLY DISCO

Woven into the story of Teddy Pendergrass is also the story of disco, without which house music would not exist today. Moreover, without the work of the musicians at Sigma Sound Studios, disco would not have sounded the way it did. That tight-knit group of Philly players uniquely influenced the sound and feel of pop music over the ensuing three decades.

“If you took all the stuff, the various labels, the same musicians and put it all under one label, you’d say, ‘Motown who?’” claims legendary remixer Tom Moulton. “The Delfonics were on Philly Groove; The Spinners were on Atlantic; Jerry Butler was on Mercury; The Manhattans were on Columbia. But [they all] recorded in Philadelphia, using the same musicians and same studio. You start adding all those records together... I mean, I’m not taking anything away from Motown, but do they have 200 Gold or Platinum albums? I don’t think so. Philadelphia has. There were so many records spread over different labels, and that’s why I don’t think Sigma Sound ever got the credit it really deserved.”

While it’s true that the talent was spread over numerous labels, the most significant of them, Philadelphia International Records, was the hub for much of the city’s output, and it had a huge impact on the nascent disco scene emerging in New York in the early part of the 70s. The men behind the label, Leon Huff and Kenny Gamble, built a mini empire of talent gathered around the Sigma Sound Studios, owned by studio engineer Joe Tarsia, who was the unsung but essential component in the success of the sound of Philadelphia. “He’s the greatest engineer that ever lived,” claims Moulton, “bar none. I can’t think of anyone who has had more influence on music and putting class into music than Joe.” Gamble and Huff still hold the record for the most r’n’b No 1s in the Billboard charts.

Having soundtracked the civil rights movement of the 1960s, it was no surprise that the Philly sound frequently showed its socially conscious side with songs like ‘Bad Luck’ (about corruption), ‘Ship Ahoy’ (slavery) and, of course, the Teddy-voiced ‘Wake Up Everybody’. Many of these themes were reflected in New York via disco’s nascent scene, too, with DJs like Steve D’Acquisto and Michael Cappello championing music with a social conscience. “I used to try to tell stories, that was my gig,” D’Acquisto told us. “I used to try and talk with the music. It changed from one story to another: ‘I love you’; ‘I need you’; ‘You’re hurting me’; ‘I’m going to leave’. Then it would be: ‘The government is going to kill us!’”

The music made at Sigma Studios in Philly has provided the base for countless house tracks over the years, endlessly sampled by DJs and producers, including classics like ‘You Can’t Hide From Your Bud’ by DJ Sneak, based on the Teddy song ‘You Can’t Hide From Yourself’, and JohNick’s ‘Play The World’, which used ‘The Player’ by First Choice, while hip hop producers, including Kanye West, have also rifled through the same vast reservoir of breaks and loops for inspiration (and samples).

IF YOU DON’T KNOW ME BY NOW

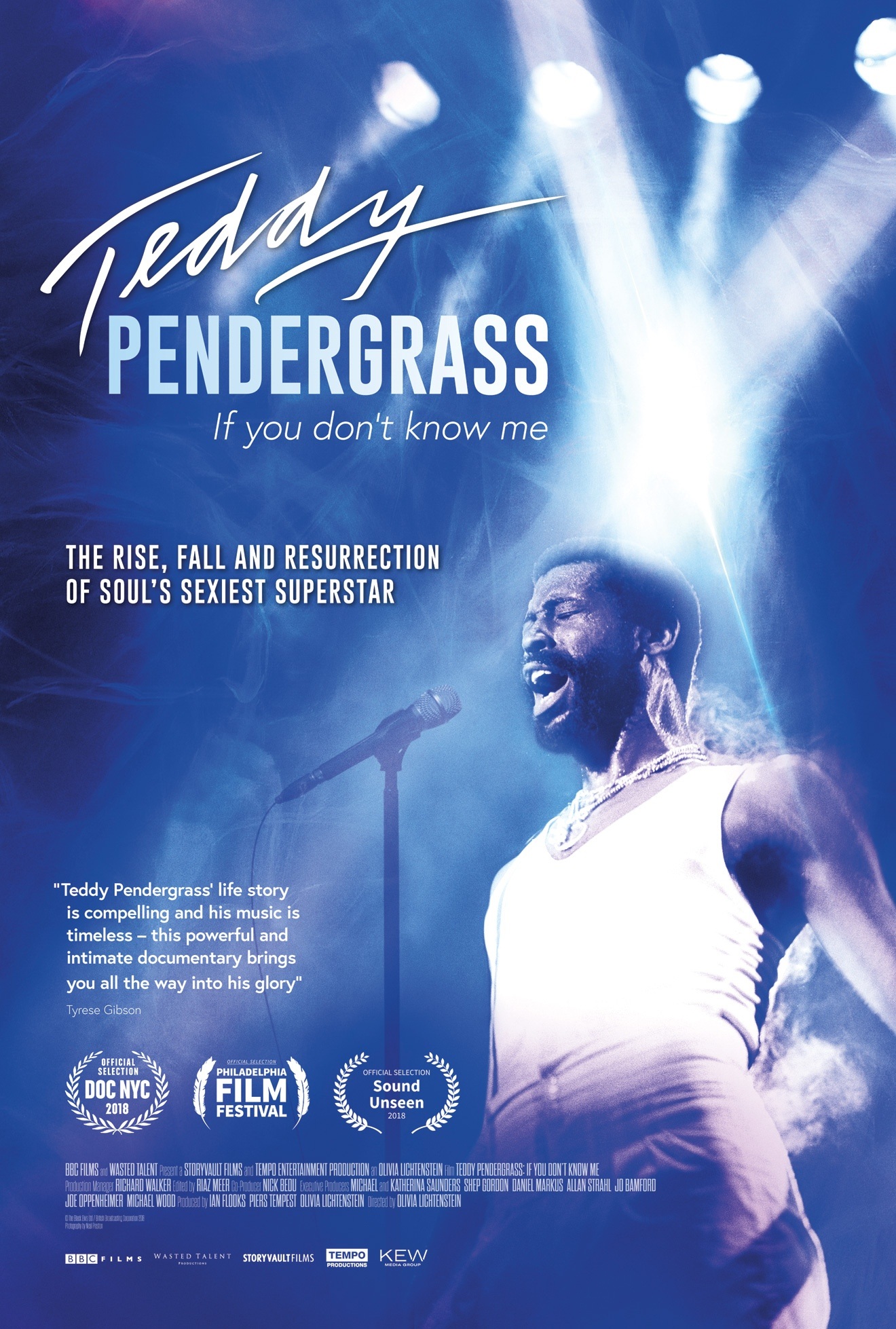

Pendergrass’ rise from street kid to putative pop star is perfectly chronicled in Teddy Pendergrass: If You Don’t Know Me, a new feature-length film about the singer’s colourful life. His father, whom he scarcely knew, was stabbed to death. Taaz Lang, his first manager (and also lover) was killed outside her home in 1978. No one was ever convicted of her murder, and rumours swirled for years that Pendergrass was somehow implicated. Then on March 8, 1982, at the apex of his career, he lost control of his Rolls Royce Silver Spirit while driving down Lincoln Drive in Philly. The car slewed across the oncoming lane and smashed into two trees. It took rescue teams 45 minutes to free Pendergrass from the wreckage. He suffered a severe spinal cord injury that left him a quadriplegic. There were also questions about his passenger, a transgender nightclub performer called Tenika Watson, who escaped largely unharmed.

“It’s the most terrible tragedy,” says director Olivia Lichtenstein. “I always felt there was something Shakespearean about it. Here he was, the sexiest man in the world, this incredible talent, just ready to fly and become a global superstar... and then two seconds in his life that changed everything forever. And to somehow have the fortitude to come to terms with that and get back on stage… the amount of courage that takes.”

Unpicking this hugely complicated story was part of the challenge for Lichtenstein. “Every film you make is a journey of discovery, and that’s the part that’s so exciting about it,” she explains. “Sometimes you start out thinking, ‘Is there really going to be enough here?’ But human beings are complex creatures, so the more you unpick and the more you delve into somebody’s life, the more you uncover. I really love that process, because it’s like trying to find all the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle and then put them together. So with Teddy, there’s what happened with Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes, the enigma of his first manager Taaz who was murdered, the car crash, plus he had a lot of relationships at the same time which made his life quite complex as well.”

Pendergrass’ post-accident return to the stage couldn’t have happened in a more public manner. He performed at Live Aid in his home town on July 13, 1985, assisted by friends Ashford & Simpson in front of 100,000 fans and a worldwide TV audience of around 1.5 billion. A few years later, the song ‘Joy’ got heavy rotation on stations in the US and the eponymous album was eventually certified Gold, an incredible turnaround for a man who’d been contemplating suicide a few years earlier.

Lichtenstein, an avid soul fan herself, wanted to raise Pendergrass’ profile and also hopefully introduce his work to a new generation of fans. “When I’ve said to people, ‘Oh, I’m making a film about Teddy Pendergrass’, some go, ‘Teddy who?’ Part of it is to do with Harold Melvin having had his name in front of the group, so [Teddy] doesn’t have the immediate name recognition that he deserves. As one of his band members says in the film, “Our success came from the mouth of Teddy Pendergrass”. So I hope this film will redress that and make people aware of who Teddy was.”

Teddy Pendergrass – If You Don’t Know Me: the Rise, Fall and Resurrection of Soul’s Sexiest Superstar is out now