Features

Features

Incandescent teacher: Honey Dijon is lighting up the world of dance music

We hooked up with "one of the world's best fucking DJs" in Paris

There’s a psychological disorder known as ‘Paris syndrome’, in which first-time travellers to the French capital are so taken aback by the reality of the city compared to its romanticisation in popular culture that they begin to suffer sickness and even hallucinations. Fortunately, meeting Honey Dijon at the Hôtel Amour – a colourful setting in the city’s former red light district, with salacious art adorning the walls – is just as inspiring as we expected. She’s the living epitome of the Parisian dream: sharp-witted, radiating confidence and extremely chic in a casual outfit that pairs a pristine black silk shirt and elegant gold chains with faded jeans and white Reebok Classics.

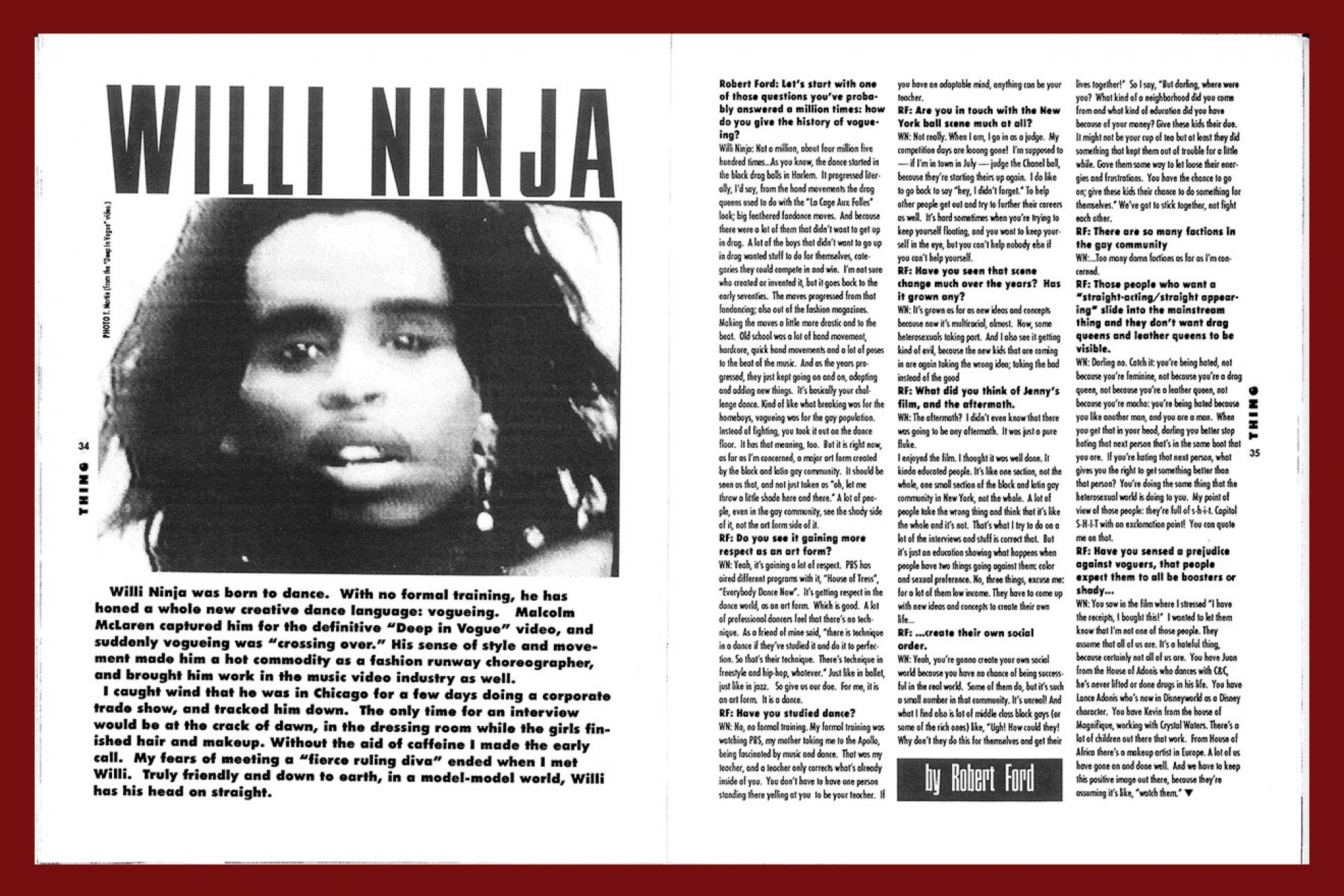

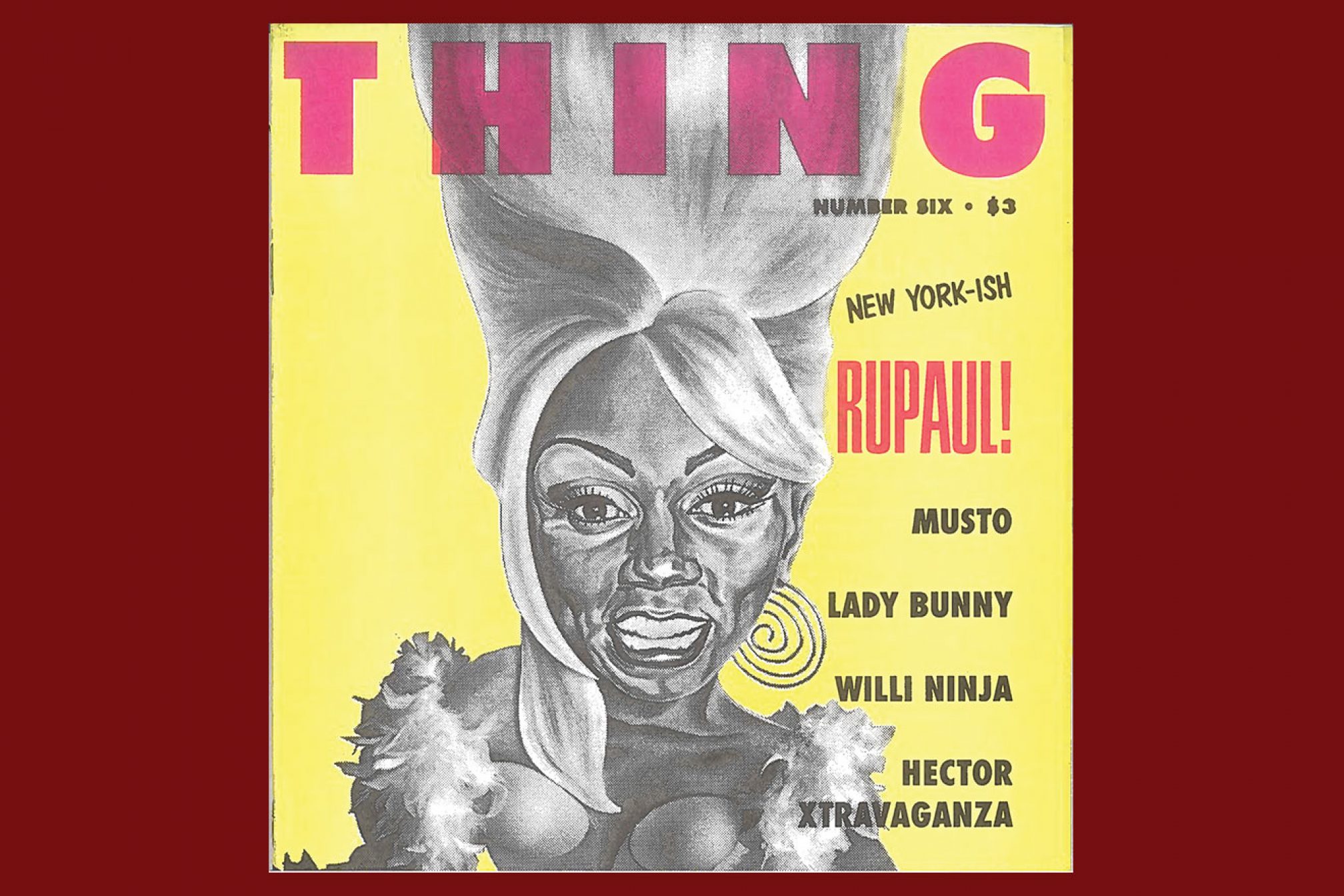

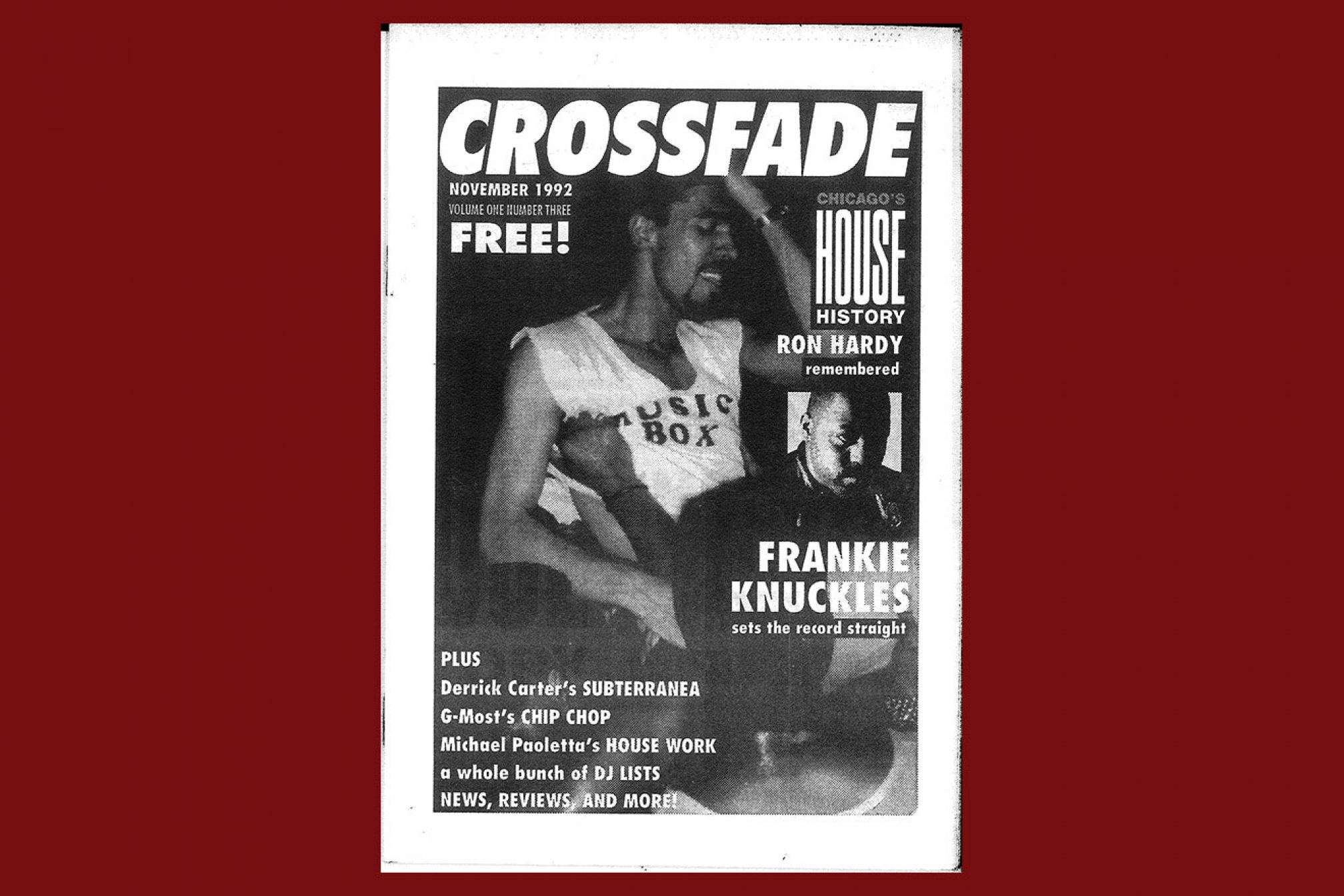

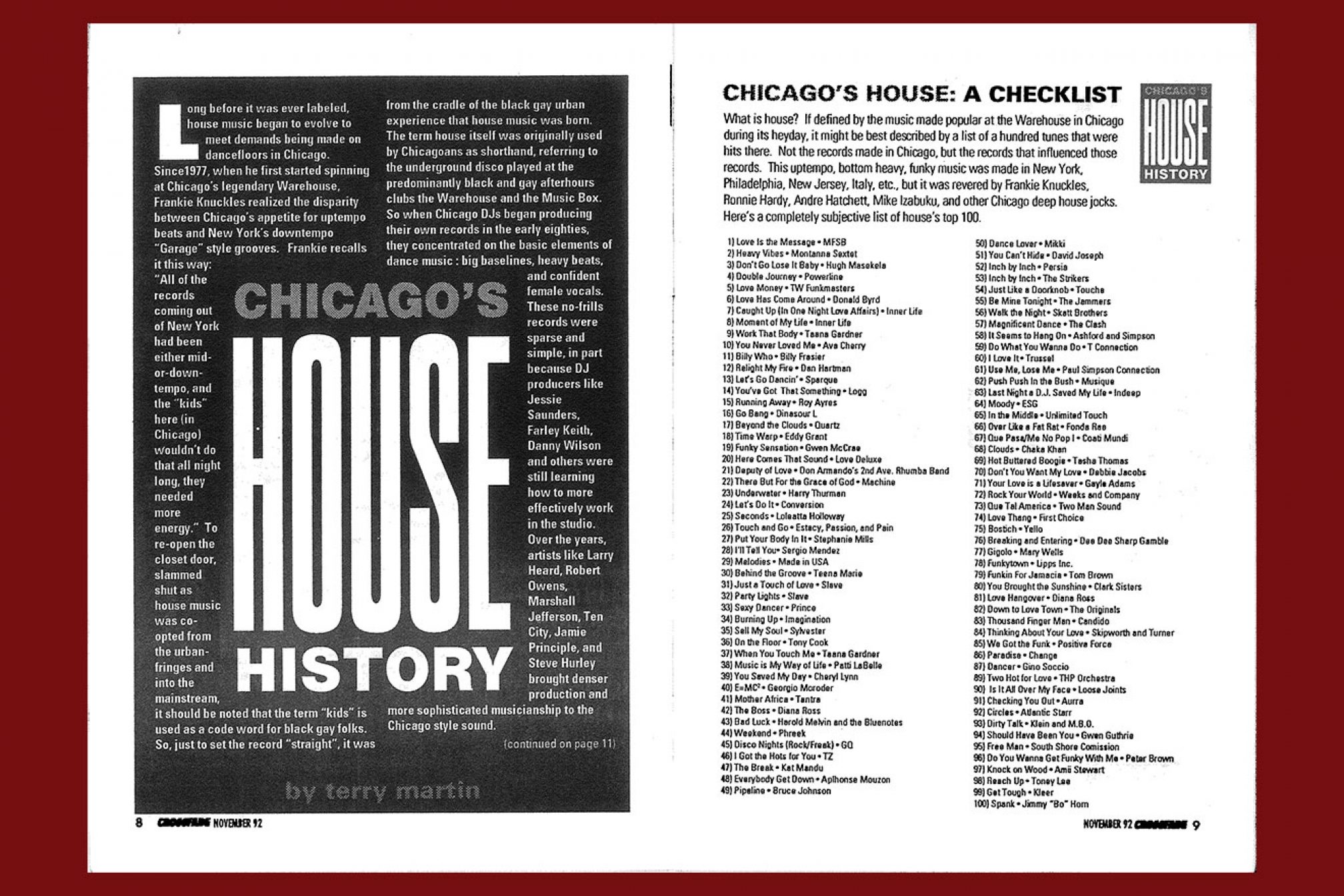

Born and raised in Chicago, later moving to New York, and now dividing her living time between the Big Apple and Berlin, Honey Dijon has been present for many of the critical cultural moments in the evolution of dance music, including the rise of house culture in Chicago and its diversification in New York. She was born to young parents who were passionate music fans, and some of her earliest memories are playing records at her parents’ parties, then listening enviously to the sounds of “amazing laughter, glasses breaking and profane language” once tucked up in bed. “I was like, ‘Oh my God, this is my world’.” She got her first fake ID at the age of 12 and attended hedonism hotspots such as Rialto Tap, Club LaRay and The Muzic Box through her teens, witnessing the heyday of originators like Ron Hardy and Frankie Knuckles. “It was like going into Wonderland,” she recalls. “These were not like clubs we know today. The dirtiest Berlin club is luxury in comparison.” Her parents were accepting as long as her school grades remained exceptional, which they did.

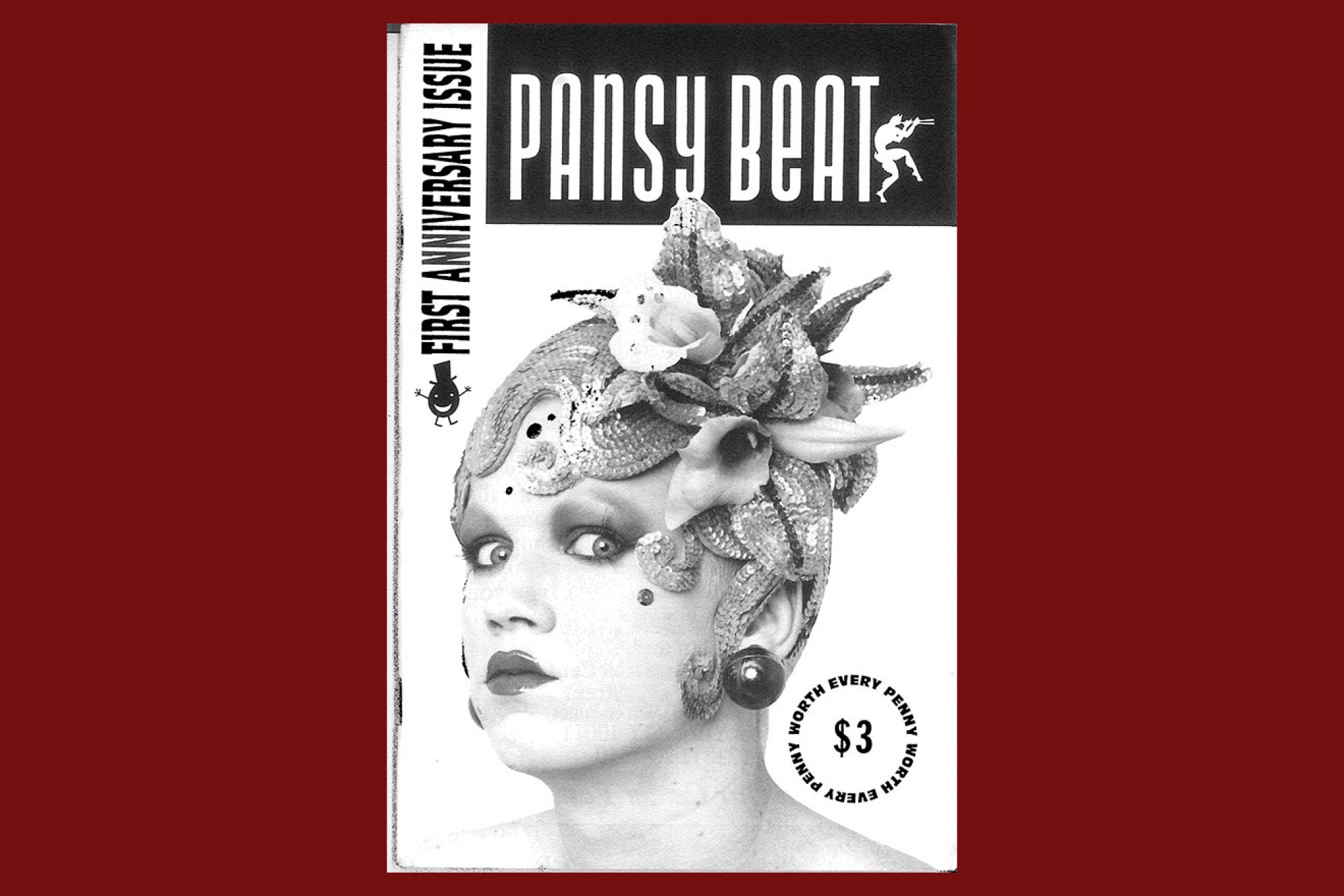

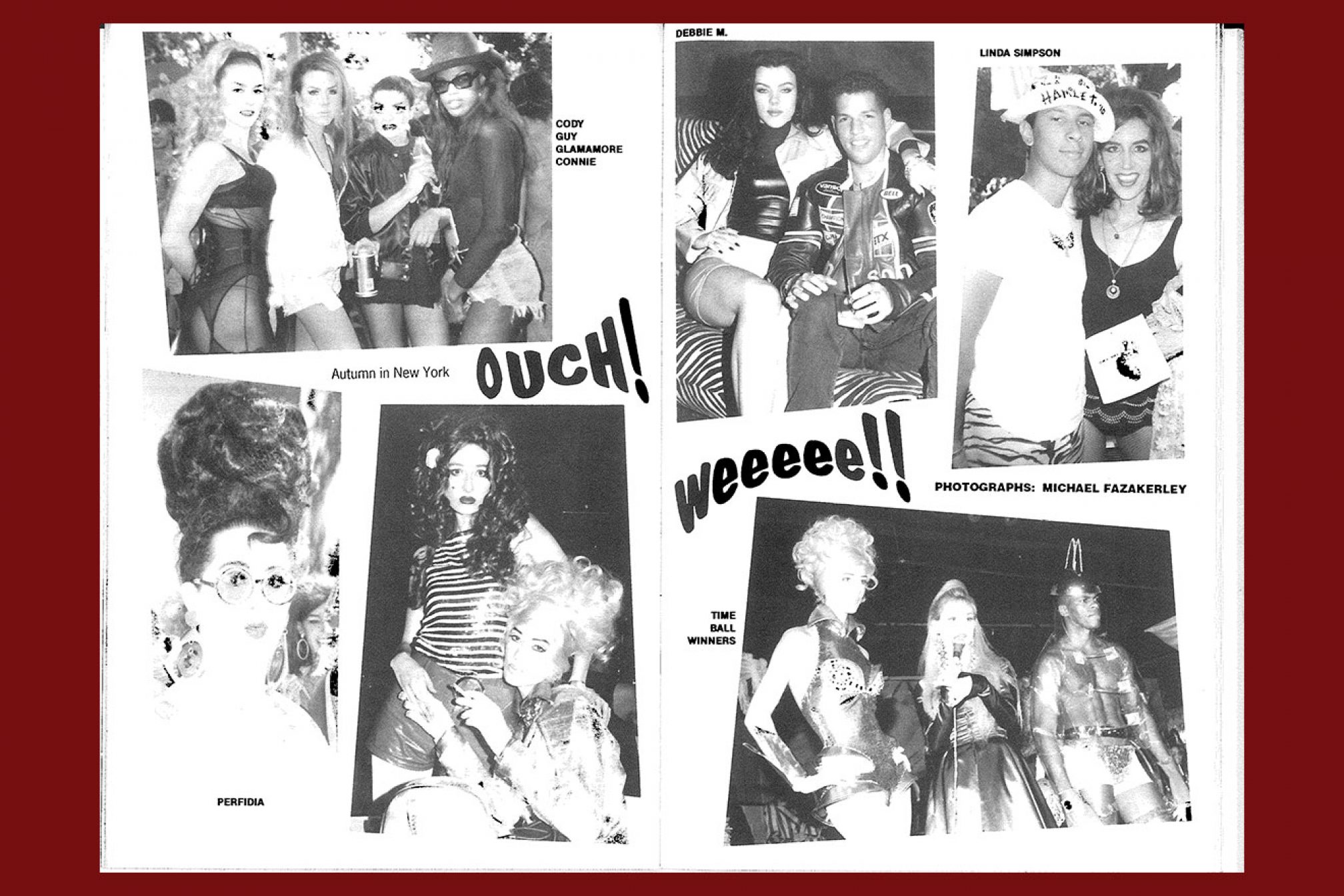

Moving to New York in the late 90s, Honey threw herself into the booming cultural scene. “I went out seven nights a week,” she says. “I still live in the same apartment because I literally used to just sleep, shower and eat in there.” Her partying exploits took her from performance poetry and drag shows at Jackie 60 and The Mudd Club in New York’s Meatpacking District to underground spots Twilo, Shelter and Sound Factory that hosted everyone from local heroes like Danny Krivit and David Morales to internatonal heavyweights such as Carl Cox, Satoshi Tomiie and Sasha. “Can you imagine? Like, fuck, this was a regular week in New York!”

Twilo resident Danny Tenaglia was a particularly influential figure, introducing her to the works of European labels like Perlon, International Gigolo and Maurizio, alongside the diverse offerings of NYC labels such as Nervous, Nu Groove, Tribal America and Strictly Rhythm. This wide-ranging exposure inspired Honey with a love for variety she’s retained through her career.

“She was always up on the latest tracks whether it was NY, Chicago, French, German, British, Italian,” says Tenaglia, who became a close friend and admirer. “Her knowledge and appreciation for more than just one style is what I respected about her the most.” And this shines through in her musical output. Her debut album, ‘The Best Of Both Worlds’, out now on Classic, features an array of collaborations with artists spanning dark techno purveyor Matrixxman to Cakes Da Killa, a queer rapper with an intense flow and knack for smart wordplay. Each guest brings fresh flavours and sonic textures to the record.

Her DJ sets are equally expansive, showcasing the breadth of a life devoted to every inch of dance culture. When she plays at festivals, she not only packs the dancefloors with punters but her fellow DJs often line up excitedly to catch a glimpse of her technical mastery and ability to blend the contents of her enviable record bag.

“I’ve been watching Honey play since I was a teenager and there’s never been a crowd I haven’t seen her wow,” says Seth Troxler. “Dance music came from black, gay culture in Chicago, and she’s a black, trans woman. There is a depth there that she understands more than any of us.” Honey Dijon has steadily built her knowledge of music since the 80s and now she’s rightfully getting her dues – as one of most respected and sought-after DJs on the planet.

Paris’s Rex Club looks like a theatre from the outside, back-lit letters proclaiming its name like the title of the latest smash hit play, and inside, Honey’s headline set unfolds with all the nuance of a grand storyline. “I grew up in a generation where music was attached to cultural and social change,” she says; much of her childhood listening closely aligned with the civil rights movement, and the way she plays even the weirdest records channels an intrinsic, powerful sense of humanity. Dropping KiNK’s remix of ‘Canto Della Liberta’ is a prime example: the production is slippery and off-kilter, but the vigorous vocal generates the feisty energy of a chanting protest march.

At one point she describes the political act of dancing in pitch-black clubs amid sexual and cultural revolution in 90s New York as like “bees in a hive”. Drawing for Harry Romero’s ‘Indy Loop’ in Rex Club – a track we’d always considered slightly flimsy – she propels the buzzing bassline to the fore with staggering impact, a sonic storm swarming the dancefloor around its queen. Enormous red lights in the shape of the letter X burn brightly on the walls like the garish symbol of ITV’s flagship talent show. But in the booth, Honey’s moves are far from choreographed. While one hand never strays far from the mixer as she cuts between four decks, her body moves with the music: tall frame jerking back and forth, fists flying loosely into the air.

At one point she mixes the stomping unreleased version of Ron Hardy’s ‘Sensation’ with her own Cakes Da Killa collaboration ‘Catch The Beat’, combining a Chicago classic with a cutting-edge exemplar of house music’s evolution. “Past, present and future exist on the same timeline in physics, so that’s how I think about music when I play,” Honey says. “I’m a facilitator of human connection through sound. I don’t give a shit if it’s classic or something made last week in some kid’s bedroom, as long as it’s dope as fuck. The bottom line is that sharing gets me off.”

As a DJ “schooled in Chicago”, Honey credits the city’s rich heritage for instilling a competitive edge to her craft that’s been a driving force in her career; “There’s three thousand DJs in Chicago so it makes you work a bit harder to stand out.” Becoming eclectic and unpredictable was a way to get recognised. ‘Catch The Beat’ in itself is a paragon of Honey’s continuing openness – how often do you hear rappers on an album that will be filed in the deep house rack of a record shop? “It was an honour to work with Honey,” says Cakes. “We come from the same lineage: POC artists who don’t give a fuck.”

And Honey’s art reflects the life experience of someone who has had to live and breathe the culture not only as a passion, but as a necessity. She recalls feeling uncomfortable with constructed gender roles from her early childhood, which made the predominantly black and Latino neighbourhood she grew up in and Catholic school she attended pretty harsh environments. “My family life was amazing – [but] once I left the house it was torture,” she says. “I got a lot of violence directed my way. I had to learn the art of survival.” There was slight tension with her parents over some of her aesthetic choices, but no more so than any young son or daughter is liable to face for, say, a tattoo or earring, and on the whole they were supportive figures who gave her the strength to be herself.

Not fitting into mainstream society, Honey turned to more subversive pursuits. The effect of her Catholic schooling was a desire to go to hell. “I don’t want to go to the land of milk and honey – I want to go where there’s sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll for eternity,” she laughs. “Honestly, I don’t want anyone to save me. Hell is the afterparty!” Partying became her primary escape, clubs being places she was able to go and express herself freely away from the glare of persecution. She recalls with breathless excitement the first time she saw same-sex couples and non-binary people openly “dancing in a frenzy”. “It was completely thrilling to see like-minded people – and to realise you were not crazy,” she says, her tone shifting halfway through the sentence from exhilarated to poignant. “I was thrust into these misfit worlds, and thank God, because everything I was vilified for has made me who I am today.”

Having been present from the early days, Honey is well placed to examine the evolution of dance music, and she’s not so sure that things have continued to progress. “Dance music has become very mono-cultured,” she says. “I miss colour in clubs. If you’re on the dancefloor taking videos you’re not bringing anything; you’re extracting. Standing there like, ‘What tune is that?’ Who gives a shit! Dance! Bring some colour, some attitude, something else.”

Honey Dijon’s lived understanding of dance music’s roots and ability to ‘bring something else’ as club culture becomes increasingly colonised by “heteronormative men of European descent” is what makes her so vital.

“She’s a fierce bitch. Dance music needs more fierce bitches,” says Derrick Carter, who has been close friends with Honey since early teens after a mutual friend insisted they meet, knowing that they’d hit it off. To this day she has a personalised ringtone in his phone, a soundbite from an argument between Eddie Murphy and Della Reese’s characters in Harlem Nights: “Are you in charge of the girls?” “I AM IN CHARGE OF THE GIRLS!” Carter is a stickler for authenticity, and also laments the whitewashing of dance music and ignorance of its black origins among the new generation. “We’ve shared and seen the ways that people try to silence you. Standing strong and being that fierce bitch is one hell of an antidote to that.”

Not only is Honey Dijon fierce, but has a fierce intelligence conspicuous in conversation: she’s thoughtful, but razor-sharp in her comments, well-read and eloquent on topics spanning gentrification to architecture to the AIDs crisis. She blames AIDS for the cultural sanitisation dance music has suffered over the years: “Not only did it take out two generations of the most highly creative people, it took out the audiences that appreciate it.” She’s also conscious of the impact racially motivated violence in America has on black music: “Dance music was born from inner-city queer people of colour, people with the most radical, forward-thinking taste in music: Ron Trent made ‘Altered States’ when he was fifteen; now think of all the black men today in America being killed. That kind of violence has always existed against young people of colour. However, with the sheer opaqueness of the oppression that is happening today, I sometimes wonder if the music and culture we take for granted today will exist in the future.”

In the age of DJs as brands overseeing vast empires of social media managers, Troxler appreciates Honey’s commitment to the issues that matter. “Aside from being one of the world’s best fucking DJs, I think what makes her popular now is she truly is one of the last DJs who is herself,” he says. “If you look at her Instagram it’s all cultural references, all about the history. This is what she lives for – this is what her friends have died over.”

Matrixxman, a newer friend who Honey describes as her “Berlin bestie”, notes the invigorating effect Honey has in the studio: “Techno can occasionally feel stifling because of all the fuckboys playing monotonous records with no soul, no spirit. Honey helps bring out some much needed funk.” Honey herself criticises “Everyone making the same records to play at the same clubs with the same DJs on the same line-ups. I’m like, you know they make one of you every year?”

Describing a childhood memory of endlessly playing records one by one on a lone turntable, she grins: “I was actually a ‘selector’ before there was even language for being a selector.” Language is something Honey Dijon thinks about a lot. Her journey of self-discovery began before she’d even reached elementary school age, at a time where there were no words for such a thing as being transgender – a label she accepts for ease of communication, but which she doesn’t feel completely comfortable with. “We’re languaged into experience, languaged into gender,” she says. “I talk about ‘transgender’ things in order to communicate to people that may not have the self-evolution that I have. But I don’t really think of it in that way. I just say I’m me. Everyone else is taken! Who else am I going to be?”

One benefit of Honey’s outsider status is she’s able to exist between boundaries, seamlessly navigating the worlds of music, art and fashion. “I didn’t (and don’t) fit in anywhere, so the arts gave me a sense of belonging,” she says of a childhood spent in clubs and reading about art, architecture, design, fashion and photography.

In the world of music she’s unique for the span of parties she plays, from exclusive underground haunts like Panoramabar to the sparkling, podium dancer house of Glitterbox at Hï Ibiza, as well as fashion parties for designers like Rick Owens, Kim Jones, Riccardo Tisci and Narciso Rodriguez. “People pick up on the joy with which she creates her magic and gives such feeling to it. She’s a really impressive force,” says Rodriguez. Asking Rick Owens what drew him to work with Honey, he says: “When I speak [like an] old-school banjee cunt, she’ll know exactly what I’m talking about.” Google it.

As we say goodbye outside Rex at 6am, Honey jumps in a cab straight to her long-haul flight back to New York. Club to the airport is about as grim as journeys get, but Honey is warm and upbeat. She’s clutching a copy of French Vogue, which she plans to read on the plane between selecting tracks for her cover mix. As her car speeds away, the darkness and stillness of the morning suddenly hits us like a cold shower. There’s no sickness or hallucinations, but Paris is a lot less colourful without her.

Honey Dijon’s album ‘The Best of Both Worlds’ is out now on Classic

This feature is taken from the November issue of Mixmag

Patrick Hinton is Mixmag's Digital Staff Writer, follow him on Twitter