Features

Features

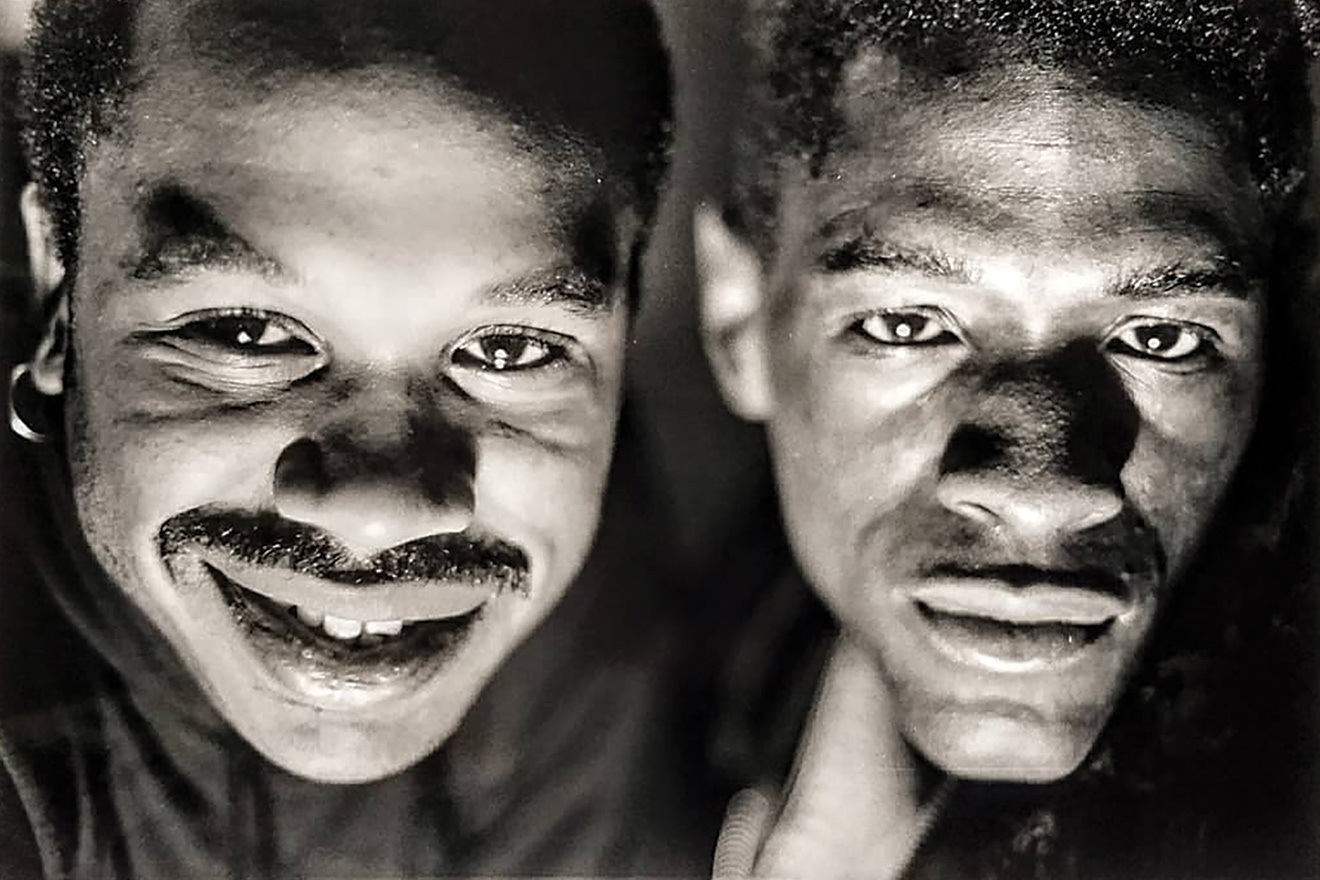

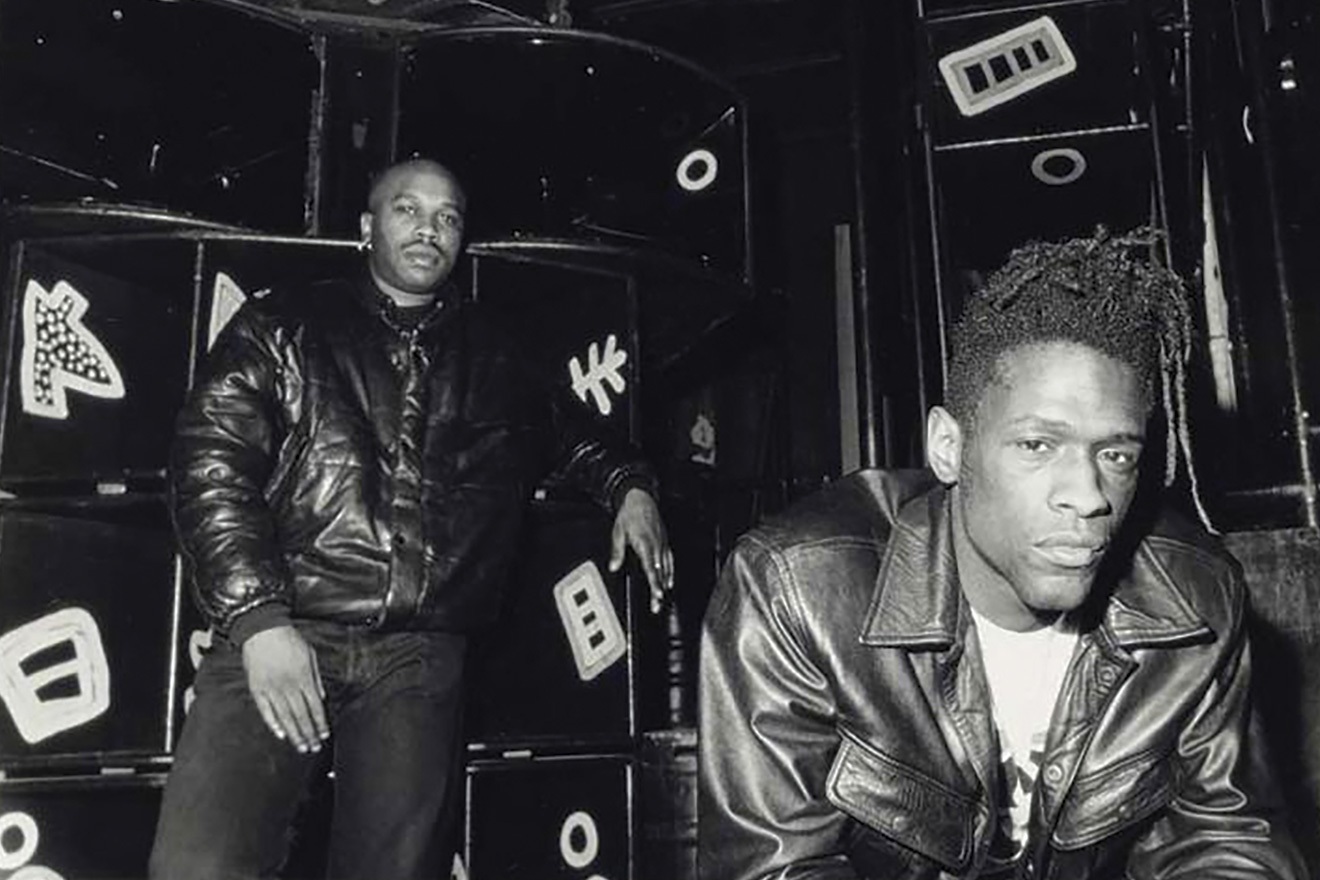

Fabio & Grooverider's Rage night was the fiery crucible where jungle and drum 'n' bass were formed

The pair behind the London party remember the dawn of a new era

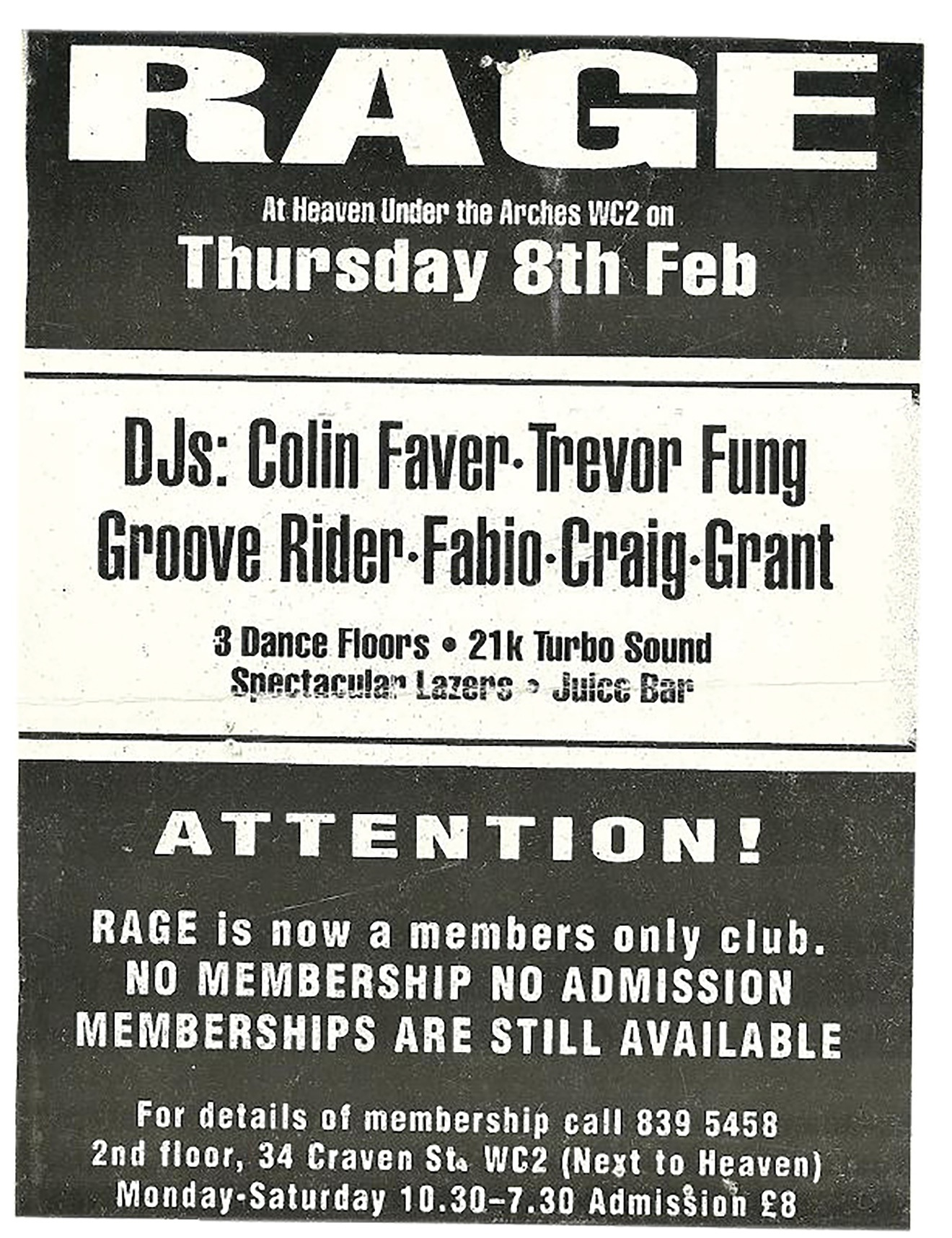

It’s 1989. Rave culture has exploded. Convoys of cars trail the motorways of the UK, heading to huge outdoor raves. Warehouses are being colonised by soundsystems. Ecstasy is transforming brain chemistry across the nation, and underground clubs are popping up everywhere. At London’s Heaven club, every Thursday night for Rage, Fabio & Grooverider are laying the foundations for what will become jungle and drum ’n’ bass, blending breaks, house dubs, hardcore, techno and whatever else they like to create something completely new. The importance of their residency is unquestionable: without that seminal era of experimentation, musical liberation, daring and sheer bloody-mindedness, breakbeat culture as we know it would not exist. Inspiring drum ’n’ bass heroes like Goldie, Kemistry (RIP) & Storm, Bailey and countless others, Rage would become a revolutionary hub where a diverse clientele congregated to experience something totally different from anything else that was going on anywhere at that time. It was equal parts exhilarating, progressive, dark and edgy, and led by two men whose taste in electronic music meant they attracted their own particular crowd. Fabio & Grooverider are the godfathers of drum ’n’ bass, members of a core group that helped create a form of music that has had a huge impact on dance music culture all over the world. Thirty years since they first started at Rage, Mixmag spoke to them about those halcyon days.

How did the Fabio & Grooverider partnership begin?

Fabio: We were on a pirate station called Phase One, based in Brixton. We’re both from South London and had mutual acquaintances, but we’d never actually met. At the station’s monthly meetings we’d say hello to each other but didn’t forge a friendship initially.

So how did the friendship develop?

F: It started because we were the only DJs on Phase One that played house. The guy who ran the station, Mendoza, had a club below the studio called Mendoza’s. It was a local haunt, a tiny little place that held about 60 people at the most. In those days Brixton was ghetto and Mendoza’s was down an alleyway, so it wasn’t the most approachable place. Anyway, his brother Chris got into the house scene and was quite tight with the crew from Danny Rampling’s night Shoom. He said Mendoza should host the afters for Shoom at the club.

And what did he say to that?

F: He wasn’t sure at first, but he phoned us both because we were the only house DJs who were on the station. You have to realise this was a long time ago; midweek clubs were a no-no back then. Secondly, Shoom finished at 2am and third, Groove had work the next day. All these things were conspiring against us and it really didn’t feel like it was going to be worth our while. Groove called me up and said, ‘What do you think? I’ve got to be at work tomorrow,’ and I was like, ‘Fuck it, let’s go and do it!’

How did that first afters work out?

Grooverider: I’d never been to an acid house rave, I just liked the music. We didn’t realise it was gonna start so late, so we got there about 11 and there was no-one there. Thinking it would get better we waited and waited. By 2am I’d had enough and we left. As we were in my car getting ready to drive off, Chris comes round the corner by himself. I thought, ‘This shit’s crashed and this guy’s wasted my fucking time!’ He comes over and says, ‘Where you going? They’re all coming now.’ I look up and see a few people coming round the corner, so I thought, ‘Alright, if there’s 20 people we’ll be nice.’ Next minute that place was rammed. People always ask me, ‘What was your big break?’ I never really thought about it because it’s all been hard work, but I think it was us staying there that night that did it. Since then we haven’t really ever looked back. That 15-minute window changed our lives. I was ready to pull off and go home!

How did you get connected with Rage?

G: Our friend Debbie, who was a regular at Mendoza’s, sorted it. We’d been to [Monday night party] Babylon, which was the night, but never to Rage. When she said there was something happening on a Thursday night I thought it was gonna be rubbish.

F: Yeah, Mondays were popping. The first time we went there, the bouncer wouldn’t let us in – which was a regular occurrence for black guys back then. We saw Steve Jackson turn up. He was a pioneer, really well known at the time. He went straight to the front of the queue and asked to be let in. The bouncer wasn’t having it and asked him who he was, he started shouting “I’m Steve Jackson from Kiss FM!” We could hear him all the way at the back of the queue.

G: The bouncer told him, “So what?” That taught us a valuable lesson: don’t go shouting your mouth off. That really affected us; we never wanted to be that guy, so we’ve always been humble.

F: Ten minutes later the bouncer let us in – he must have felt sorry for us. We walked in and that just changed everything. I remember seeing all the smoke machines and mad, mad lasers. Me and Groove just stood in the middle of the dancefloor with everyone around us going mad. We were just soul boys. We didn’t have a clue what was going on. I looked up and saw Paul Oakenfold; that was the first time I’d seen everyone facing the DJ and watching them. I thought, ‘What the hell is going on here?’ and then started thinking, ‘I wanna be that guy. I wanna do that.’

And you ended up playing there not long afterwards?

F: Yeah, Debbie hit up Groove and I remember him telling me we had a little audition thing down at Rage for the upstairs room, the Star Bar. Clearly nothing was going on up there and they just wanted to get someone in to play. The plan was to tout it as a little VIP room where people could pop in, with the main event happening downstairs. But that’s not what happened. We got in there and it became like a separate night. From this tiny spot we had, it became the spot. Sometimes we’d get down there at 10 o’clock and have to push past a queue just to get in and get started. We had it kicking off.

G: The main dancefloor was suddenly empty – everyone was upstairs. One week, Kevin [Millins, the promoter at Rage] asked us to cover Colin Faver and Trevor Fung, who hosted the main room… and we took it, we took everything.

F: The second we played the last tune, Kevin burst into the DJ booth and said, ‘You lot are residents now, you’re down here.’ Colin and Trevor were our idols and we felt bad, but we were young and ready for it.

G: It wasn’t up to us, anyway: people voted with their feet. We would’ve been happy if we stayed upstairs, we were just happy to be DJing.

What was it actually like in Rage?

F: It was ahead of its time: no other club was like Heaven at the time. The soundsystem was lashing, they had this amazing light system, the lasers in there… it was the perfect set-up for what we were doing.

G: Richard Branson owned it!

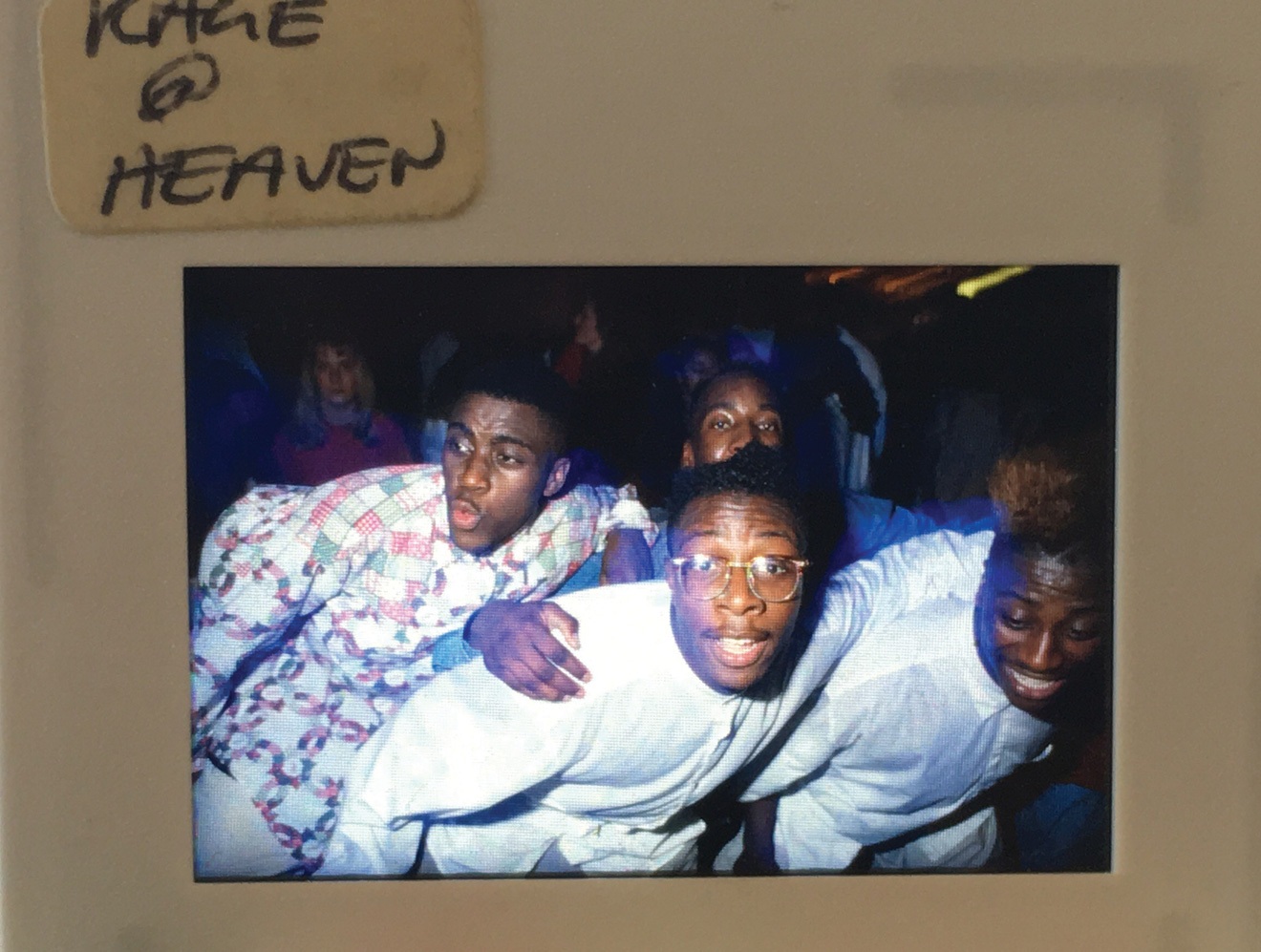

F: We felt privileged to play. Being as young as we were, it was amazing to be running things at this place. We brought a young crowd, a mixed crowd. No disrespect to Rage before, but it was very housey in there. We brought an urban vibe. We’d have Amanda de Cadenet, Emma Ridley and all those It girls down every week, proper ICF football hooligans, North London gangsters, people from Brixton, but it was nice in there.

G: They’d just get on with popping Es.

What was it about what you were playing that switched things up?

G: Just a different perspective on the music. We were predominantly dub-orientated. Downstairs [before the pair moved] it was A-sides and vocals, whereas we were purely about the dub versions, that’s what we liked. No singing business.

F: Downstairs was a lot more purist, upstairs we were doing madness. They just let us do our thing and we went in. I don’t remember ever thinking, ‘I can’t play this.’ If we liked it, we’d play it. That was the benefit of getting us to do upstairs: it was low risk. They had nothing to lose, and neither did we.

What’s kept your friendship going for so long?

F: We’re different, but we’re also very similar in the way we’ve been brought up. We have unwritten values that we both hold on to, we’re very true to each other and very close. I don’t even know what the magic of that is. We’ve never sat down and formulated a plan, ever. Even now people try to push us to do certain things, or to think about how we present ourselves and all that, and it’s really challenging. We’ve always done things our way.

Thirty years on, Rage’s spirit is still alive!

G: Rave culture is still out there, and that’s what Rage was. It was the starting point for a lot of people.

F: Back then if you’d have told us, ‘Twenty-five, thirty years from now people will still be talking about this night,’ we’d never have believed it. But that’s a testament to what it was and what we did I guess. There were other nights that were around at the time, but everyone talks about Rage. It was a combination of me and Groove being really daring, not knowing what we were doing and it working somehow, plus having a boss who let us do what we wanted. He got a lot of stick from the old-school Rage lot, but he was like, ‘Fuck ’em!’ He didn’t give a shit. He weren’t even into the music but he saw what we were doing. He saw the vibe and the energy of it and went with it. Kevin knew, he knew at the time actually, that something special was going on.

What does it mean to you guys for that legacy to still be alive, to still be inspiring people and keeping the music moving forward?

F: It’s a lot man, it’s a lot for us.

G: I’m just glad I’m still around. So many people have moved on, or passed on. I’m just glad it’s being called legendary and that I’m still alive.

F: Until people started talking about it, we didn’t realise how special it was. It’s not like we’re hanging out going, ‘Boy, we changed the game you know!’ Even if we do acknowledge it like that, it’s with an air of surprise. It’s like, ‘Can you believe all that happened?!’

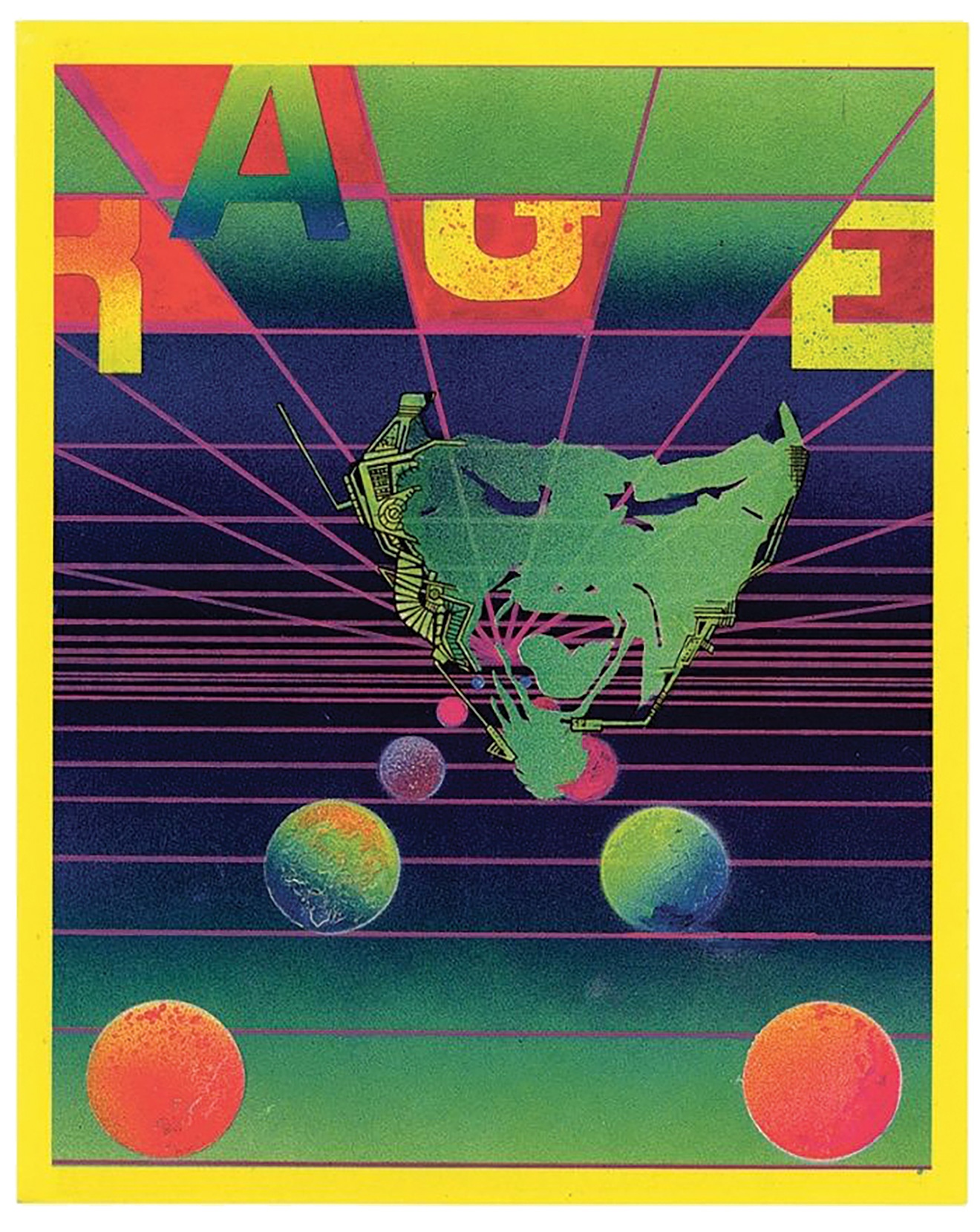

'RAGE', a 32-track album compiled by Fabio & Grooverider, is out now on four separate double-vinyl LPs, double CD, digital download and stream

[Flyers: Pez Flyers]

Marcus Barnes is a freelance journalist, follow him on Twitter

Read this next!

History of the word rave in two minutes

The history of acid house in 100 tracks

Acid house fashion was outrageous and we love it