Features

Features

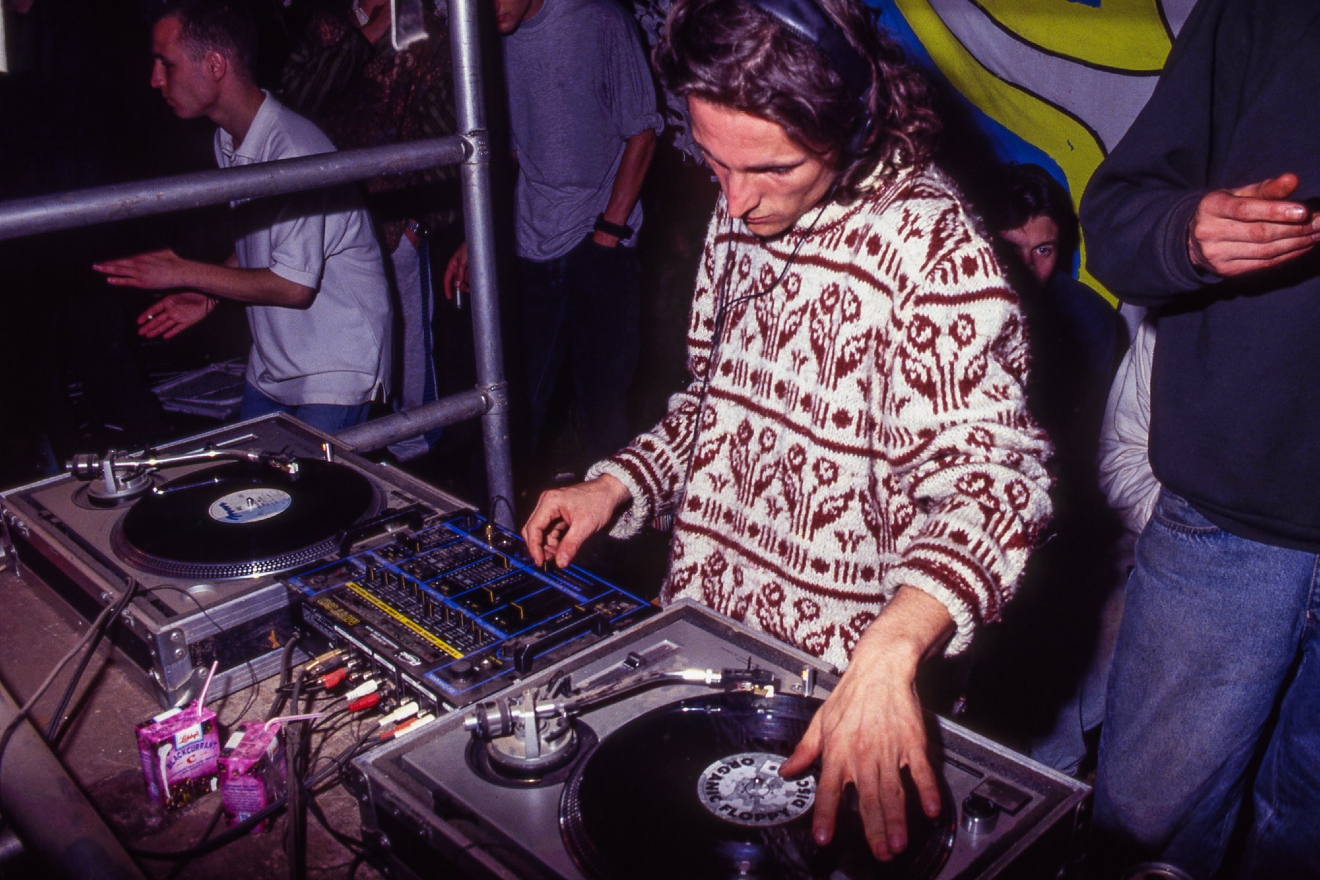

"It’s never too far": The inside story of Castlemorton — history's most infamous rave

Read an excerpt from DiY founder Harry Harrison's new book, Dreaming in Yellow: The story of DiY Soundsystem

Never has there been a more turbulent time in UK politics than in the 1980s. Through a new era of young ravers discovering evolving variations of electronic music, political restraints tightening, and an allure to join a growing counterculture, the coming-of-age put all their efforts into free parties. In the final ten year lead-up to the new millennium, youth rebellion grew stronger and soundsystem culture was created. DiY was one of the first house-focused soundsystems in the UK finding its feet in the Midlands, and once it lifted off, brought a fanbase bigger than they could have ever imagined. DiY by name, DiY by nature, the collective grew immeasurable amounts finding its way overseas to a peak-era Ibiza where the parties continued, this time legally, and developed international fans.

By May of 1992, DiY Soundsystem reached its most lawless and revolutionary peak. One of the most infamous free parties of all time, Castlemorton Common Festival, took place with the help of the DiY collective inspiring the legislation of 1994's Criminal Justice and Public Order Act. The historic event signalled a change in these seminal beginnings, and the counterculture now faced backlash as a result of Castlemorton, the biggest and most hedonistic free party in UK history. DiY founder Harry Harrison has now documented the story of the soundsystem's anarchic beginnings in a new book, Dreaming in Yellow: The story of DiY Soundsystem, due for release on March 23 via Velocity Press. Read an excerpt set around the collectives epic rave at Castlemorton below.

It's late evening on Friday, May 22, 1992. My oldest friend and I had walked slowly, disbelievingly, up the small hill and were now sitting on the grass, pleasingly cool after the heat of the gloriously radiant spring day. Silently we looked out across at what had been, until a few short hours ago, a peaceful and forgotten corner of middle England. Now, in the settling, liminal dusk it resembled some giant military operation or perhaps a huge, dark creature with endless rows of bright white eyes. In every direction, visible from our vantage point, luminous streams of headlights flowed along the entry tracks and the roads stretching into the distance. Who knew how many vehicles were arriving; certainly several thousand cars, vans, trucks, buses and horseboxes were pouring onto this enormous common laid out below us containing unknown numbers of ebullient revellers. Twenty-four hours earlier we had never heard of this place. Castlemorton had just been another name on the map, another quintessentially sleepy English shire, certainly not the sort of place where history is made.

On that portentous night, Pete was two days shy of his twenty-seventh birthday, I was eighteen months to the day younger. It had been ten or so years since we had met at an underage drinking establishment in Bolton and had been through innumerable existential rites of passage together during the intervening, tumultuous decade. With others, we had been founding members of a music collective that had grown exponentially in tandem with the explosion of dance music and had, beyond our wildest expectations, succeeded in uniting our twin passions of music and protest into a remarkable, cohesive alliance.

Read this next: "We were young, restless and skint": Smokescreen Soundsystem celebrates 30 years

Pete had introduced me to Crass, the seminal anarcho-punk band and in their brilliant pamphlet ‘Mindless Shocking Slogans and Token Tantrums’, they quoted Wally Hope as declaring:

"Our temple is sound, we fight our battles with music, drums like thunder, cymbals like lightning, banks of electronic equipment like nuclear missiles of sound. We have guitars instead of tommy-guns".

Only we had replaced guitars with acid house. Seemingly out of nowhere, house music had shown every possibility of providing the perfect weapon with which to dismantle, in some small but meaningful way, the anodyne and monotonous world which we had grown up in and largely rejected. From small parties around inner-city Nottingham in the summer of 1989 onwards, our collective, known as DiY, had tried to use the irresistible power of these new electronic sounds as a musical weapon to challenge convention; to attempt to unite people beneath a banner of liberation and pleasure. And now here we were, witnessing the effects that the actions of our group, and those of many more, had catalysed into this huge free festival.

Various soundsystems, including our own, were transmitting their rhythmic pulses across this darkening common, mingling with shouts of joy, recognition and exhilaration. This looked, smelled and sounded like revolution; a righteous revolution against the entrenched and heartless establishment which had been quietly and ruthlessly running England for centuries. We had intended to shock, we had intended to challenge and now the sheer scale of this revolution had become clear; magnificent yet terrifying, ranged endlessly below us, looking as if for once we were winning.

Read this next: How classic cars and soundsystems connect Southall residents to their Indian roots

The first free festivals we had attended many years before had been small, myopic and backwards-looking affairs, culturally and musically outdated, but now we had arrived at this - a whole generation seemingly drawn to these relentless beats and their concomitant clarion call to social action. I turned to Pete, sitting next to me on the grass and voiced my fears, saying:

"You know what, I think we might have pushed this too far."

To which Pete, looking out over the great chaos below, just replied, quietly:

"It’s never too far."

Dreaming in Yellow: The story of DiY Soundsystem, written by Harry Harrison, is out on March 23 via Velocity Press. Find out more about it here.

Gemma Ross is Mixmag's Editorial Assistant, follow her on Twitter