Artists

Artists

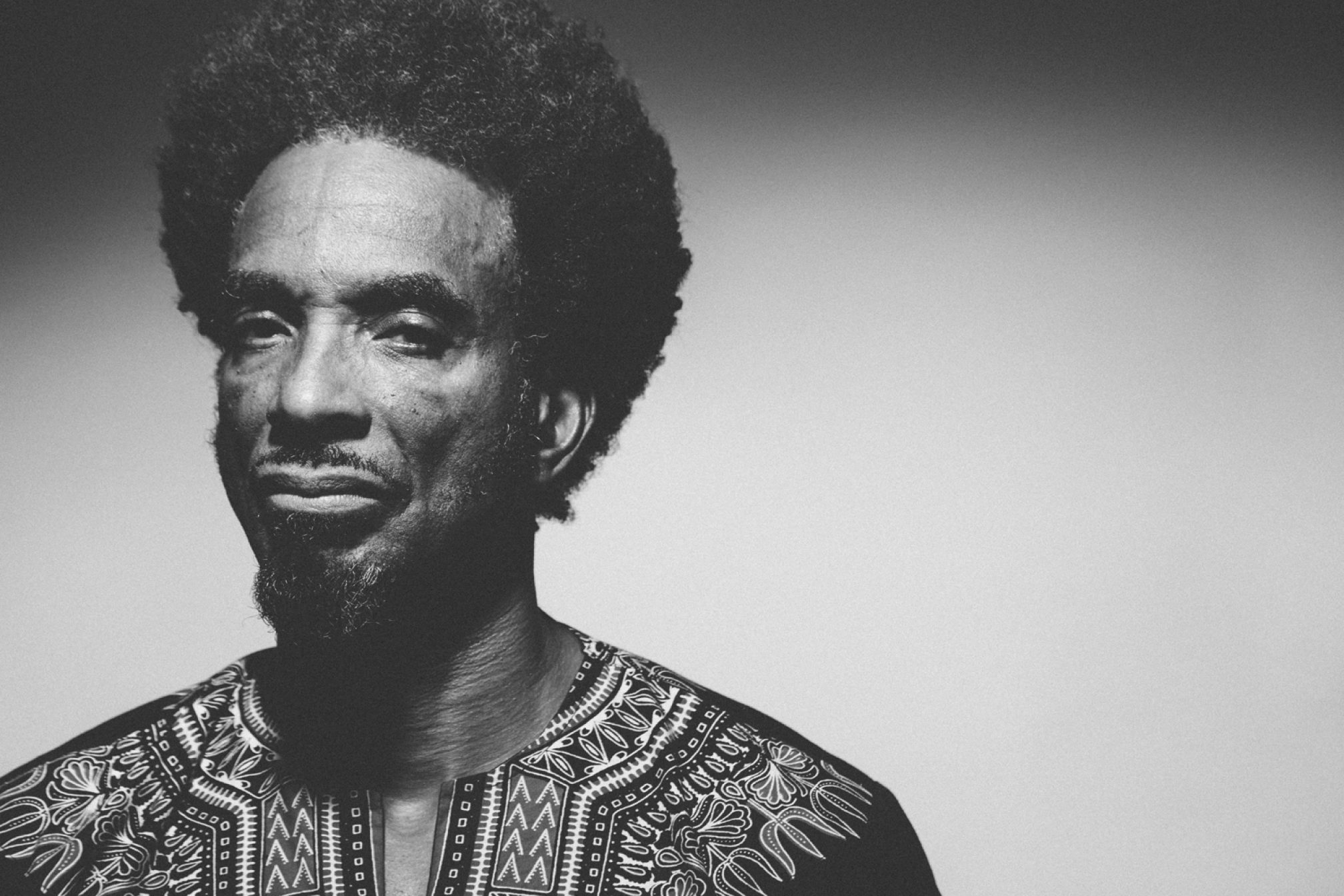

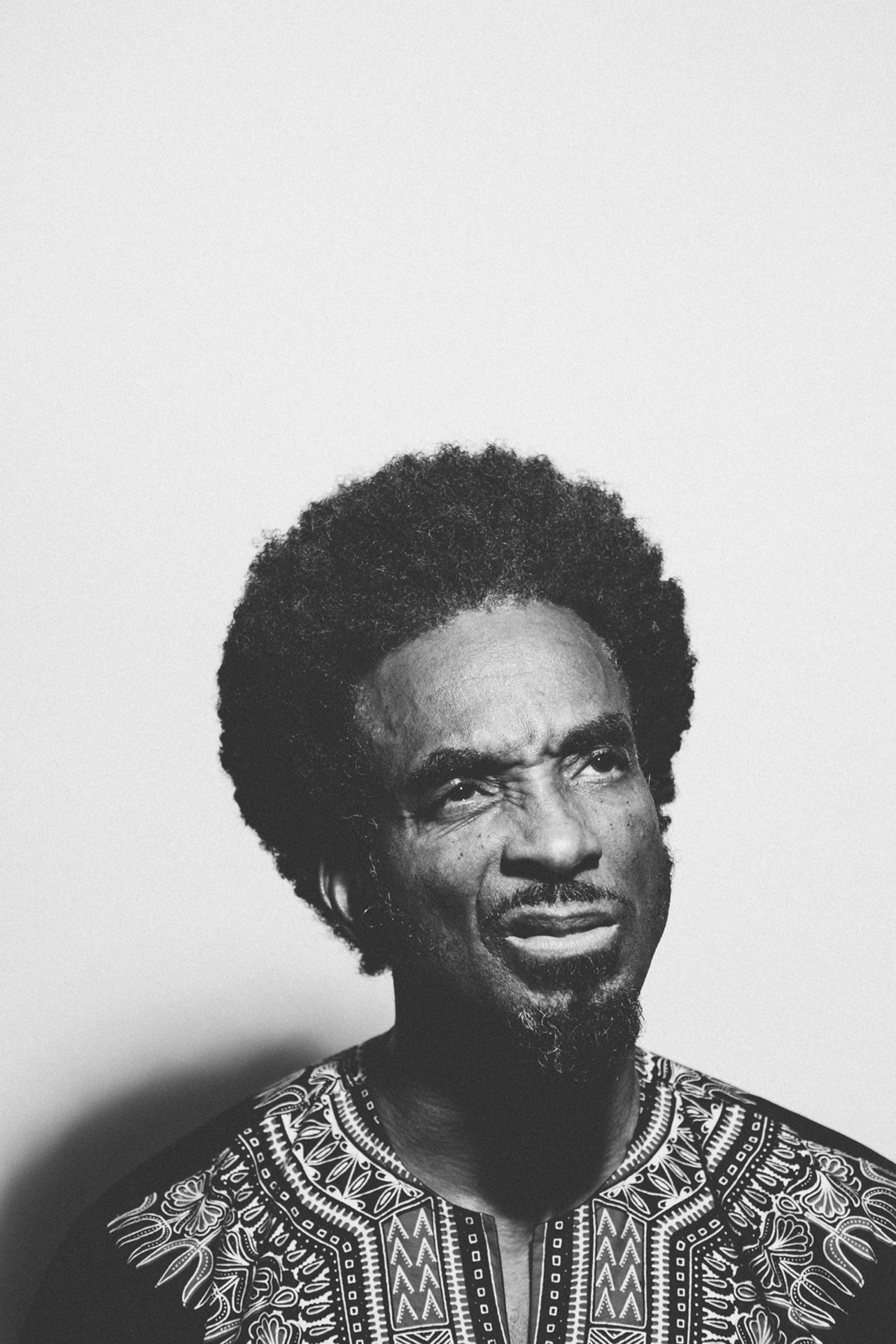

Detroit original: The tao of Amp Fiddler

From teaching J Dilla to use a sample to his relationship with Moodymann

When it comes to shaping modern music, the influence of Detroit – the home of Motown and techno, Eminem and The White Stripes – is incomparable. And for the past 30-plus years, one musician has been the red thread stitched through the sounds of this city: Joseph ‘Amp’ Fiddler. From a youngster playing keyboards with the Grandmaster of Funk, George Clinton, and his band Parliament-Funkadelic, to setting a young J Dilla on the path to stardom by teaching him the sampler, and his long-standing musical relationship with Moodymann, Amp Fiddler has had an impact on many. Here’s some of the wisdom of a funky original.

On growing up in Detroit

One of my early memories was watching the tanks go past my house during the Detroit riots in ’67. It wasn’t scary: we just felt strongly that we had some black leaders that were confident about representing black people, like the Black Panthers. My sister was a hippy and she came home with some of her friends, who were Panthers. I was too young then to have any power to do anything about it – I was the youngest of five, you didn’t know about guns and self-defence – but it was empowering, seeing those black men in their outfits. I remember asking my mom to go out and buy me a tam [the Black Panthers’ trademark beret], a black turtleneck, a jean jacket and some jeans.

On what changed after 1967

There’s still a struggle for equality in the US, even though we’ve had a black president; police are still killing kids, and the people who killed them are being released, or not even being imprisoned for it. It’s ludicrous. But I want to be positive for the future. I’m confident that one day, people will stop judging someone by the way that they look.

On growing up with music

There was a baby grand piano in my house when I was born. When I went to high school, my mom made me take piano lessons. I hated it. I didn’t like the lady, or her lessons. Then, one day, my friend and I were in Grinnell Bros’ music store in Detroit. He played the guitar – back then, every kid was a musician in Detroit, and we were all playing in our basements or garages. And we went to this store to steal, and I said to him: ‘I ain’t going to steal any pedals today.’ While I was there I got talking to an old lady who taught piano, and I signed up; it was seven dollars for half an hour. [She was called] Miss Whitney, and she was about 84. From then on, I was all in.

On working with George Clinton

George is the shiiiiiit! He’s my biggest musical hero. For a funk musician in Detroit, the ultimate gig was to be in Parliament-Funkadelic. I was a funkhead, and I’d been producing my girlfriend at the time. She took some demos to George, he liked them and wanted me to come back and do some sessions with him. I had a job in the suburbs, at a store called Incognito. It sold alternative clothes, modern shit. They sold Doc Martens when nobody else in the city was selling them. I remember that after the session for George, someone dropped the cheque off at the store. I showed it to the owner and he said: ‘This is crazy! A cheque from George Clinton!’ He called his wife over to take a look. They played a lot of really cool music in that store, music that opened my ears to other things – alternative music, like Cocteau Twins. I lived with George out in California for a time and he taught me a lot of things, including about literature. I didn’t really read much [back then]. He inspired me to do different things, to pay attention to shit that was more important than just sitting around hotels and doing nothing.

On teaching J Dilla to use a sampler

He was badass from the moment he started making music. One day, before they became Slum Village – they were part of a coalition called Ghost Town then – these kids came by my house and said they wanted to make music. I’d bought a bunch of equipment with my first advance [including an Akai MPC60 sampler]. They had heard the music coming out of my basement. And it was loud! They said: ‘You make music, we rap … can you help us?’ So I told them to come back tomorrow.

They were cool kids. I could tell they weren’t going to be a problem. I said: ‘Somebody’s gotta learn how to use all this equipment, someone’s gotta make the beats, because I don’t have the time.’ And they said: ‘Well, James [Yancey, aka J Dilla] makes the beats – that’s what he does.’ He had been making tracks from beat tapes. And he was amazing because he had one song that had like five or six different loops.

I put them into the MPC, showed him how to do it. He was watching me all the time. He’d already worked out the difference between verse and chorus. Most people, first time, don’t get that. I knew he was special from that point. He used to come by every day, just to learn more. My premise was to put Detroit hip hop on the map. I knew that Dilla was going to make a difference.

On his friend Kenny ‘Moodymann’ Dixon Jr

My A&R in London told me I needed to meet this guy who lived in Detroit called Moodymann. I just said: ‘Well, I ain’t met him yet!’ I would ask around because I didn’t know who the fuck this guy was. One day I was doing sessions with a singer and saxophonist called Norma Jean Bell. Me and my brother Bubz [a bass player] were on a couple of songs, and there was a guy at the session called Kenny. We went back to his studio and played with him. And he had this record by Moodymann. I asked him: ‘Is this someone else you produce?’ And he said: ‘Nah, that’s me!’ This was around 2003, and I needed a couple of songs for my debut album, ‘Waltz Of The Ghetto Fly’. Kenny has a different process: he’s raw, but he reminded me of George Clinton. We’ve been friends ever since. We’ve just finished a video for my ‘Return Of The Ghetto Fly’ single which ended up with both of us skating around this roller rink back in Detroit!

On dealing with tragedy

I’ve lost both of my parents, but it’s even worse when you lose your children. My son and I were closer than anyone else on this planet, apart from my mom. My father passed first, in the 70s, and then my mom, in 2006. My son [Dorian, a drummer who died of complications from diabetes] in 2009. That knocked me way back. Then my sister in 2012, and brother Bubz in 2016. People ask me to sing on tracks sometimes, and I don’t have the focus to even finish it. Without my friends – people such as Kenny, who I worked with on my new album, ‘Amp Dog Knights’, for his label, Mahogani – I wouldn’t get through stuff.

On rebuilding his own piano

I’m learning how to restore pianos. I took a baby grand piano apart and put it back together: I put new keytops on it, then all new strings and pins, which I did two weeks ago. When I get home to Detroit, I have the last of the strings to put in, and then I can start practising. Doing things like that helps to keep me motivated, but producing things in my house is a slow process. I’m used to my son being in the basement playing drums, with my brother upstairs playing bass, and I’d be on the middle floor playing piano. Now they’re both gone, it’s too quiet. I get into a real deep depression; I need to get more people in the house with me.

On Donald Trump

I’m hoping that eventually, he starts making better decisions. That’s all I can say about him. I don’t approve of the choices he makes. I just hope he gets better at them.

On his ghetto fly style

I would sit on my porch when I was a kid, watching all of these guys walking past who would be seriously dressed. There would be a whole swagger to the way that they walked. Years later, when I was in New York, I saw this guy and it was the same thing. Back then, people called it ‘pimping’. He had a real strong walk that was like a waltz, like he was dancing – that was the way that the brothers walked. And that’s where the title for my debut album, ‘Waltz Of A Ghetto Fly’, came from.

On his love of clothes

I’ve kinda slowed down now, because I have too many clothes, but I saw a guy on the train earlier with a Harrods bag and some shiny shoes and I was like, ‘Damn! I gotta shop at Harrods again!’ My milliner just called me, actually –Otis Damon in Atlanta. He makes bomb ghetto fly hats. And there’s a guy here in the UK called Maurice Whittingham, in Birmingham. Badass clothing. I could go broke when I come to London!

On encouraging kids to play music

My son always wanted to play music, and I encouraged it. I think we’re losing that, because a lot of kids today are not having music as part of their education anymore. It’s not in schools. It’s becoming a lost thing, which is terrible, so I’d love to start a programme that will help teach kids. Learning music has a big influence on all your other academic attainment. Maths, English ... it affects everything.

On faith

I’m not religious, but I have a faith. At certain points, I ask God why I’m in the situation I’m in, why I keep losing members of my family. And sometimes it makes me lose my faith. ‘How could you do this to me?’ The only thing I can do is to keep making music. It’s what I’m here for. This is my purpose. I have to stay strong. Keep the faith, and keep doing this. Move forward.

Amp Fiddler's album 'Amp Dog Knights' is out now on Mahogani Music