Culture

Culture

Deep inside

Clink Street was the birth of rave culture

It is June 1988. In the cobbled streets of Bankside, between Southwark Cathedral and the nearby bridge, steam pours from every vent and gap in the walls of an old warehouse down Clink Street. It’s like a crazed pressure cooker. Outside, a queue snakes all the way down towards the cathedral, while the KLF’s US police car is parked surreptitiously by the kerb.

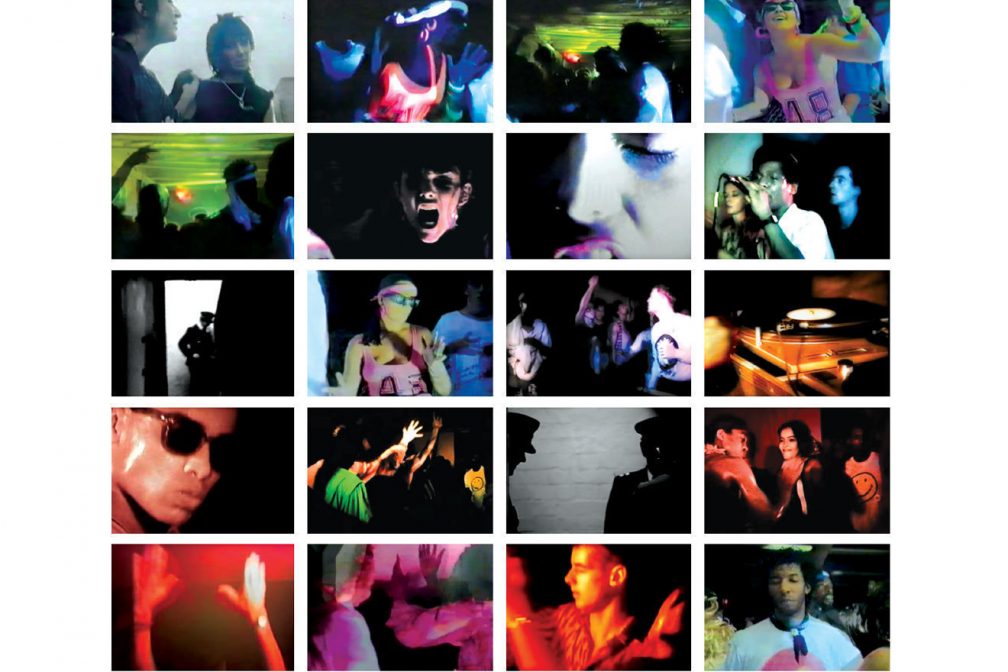

Inside: a cacophony. An assault on the senses, the smells, the din, the whistle posse in full flow, dry ice hanging in the air, sweat dripping from the ceiling – from everything, in fact. Tough Chicago house and Detroit wails bounce off the Victorian brick walls as bodies perform a robotic ritual, somewhere between communion, dance and mayhem.

Today this part of London has changed irreversibly. Bankside is now a tourist trap with Clink Street Museum, the chi-chi gourmet Borough market round the corner and the re-imagined Shakespeare’s Globe a stone’s throw away. In 1988 it was an empty, desolate dystopia, where Canary Wharf was a dream in a speculator’s mind, the Shard and Gherkin many years from even that and it still felt as though we owned the dirty streets of London.

There are many tales of acid house. The firsts, the wheres, the whos and the best. On the Balearic tip, came Future, The Trip, Spectrum and Shoom, inspired by Afredo in Ibiza. But on the street side, allied to the London reggae sound systems, there were The Dungeons on Lea Bridge Road, Mendoza’s in Brixton, Labyrinth in Dalston and, of course, Clink Street.

The iconoclastic Mr C was a resident there: “It was different. It wasn’t like anything we’d really seen before. Obviously there had been a couple of rave parties that had gone on; Hedonism being one of them. But there wasn’t anything that had been acid house in a warehouse situation like that before. The crowd was different. It was like London had come together in a demonstration against discotheques. Discos before [house] were full of football hooligans and fighting and casuals and it was all a little bit… daft. Clink Street was a real cross-section of different sorts of people, colours and classes. One of the things that made it so interesting and exciting and vibrant was that mix.”

The Clink Street parties were more formally known as RIP (Revolution In Progress) by its promoters, north London couple Paul Stone and Lu Vukovic. The pair had been originally turned on to house not by the sun setting in Ibiza, but the more prosaic (but highly influential) Jazzy M’s radio show on LWR: The Jackin’ Zone. Investigating further, Stone was introduced to Kid Batchelor, then an associate of the Soul II Soul soundsystem and an early house evangelist. After staging a few parties in Eversholt Street, near Euston, Stone and Vukovic found an old rehearsal space in Bankside, down the road from where Shoom was happening in Southwark.

“By June, I was raring to go but the first night all the security ran away when the police turned up,” says Stone. They never opened. “I thought I’d give it one more go, ’cos I had a bit of cash left. At ten o’clock there were a few people dribbling in. But as the pubs started to shut, there were droves of people started to come. By 3am it was rammed. Absolutely rammed. People out on the streets. Smoke. Strobes. It was all going off everywhere. People were turning up suited and booted. I don’t know what happened to their suits, but they weren’t coming out with them.”