Features

Features

Road Trippin': Through the roots and rise of the U.S. West Coast bass scene

Bass music has always been a fixture of the U.S.' flourishing West Coast scene

The unmistakable sound of muffled bass thrummed on the sidewalk on an atypical Sunday night in L.A.’s Highland Park. Inside an intimate dive bar better known for its live jazz and Monday night drag shows, writhing bodies bedecked in billowy harem pants and crystal pendants populated the dance floor. A few bar regulars were huddled in the back, watching with fascination as neo-hippies flooded through the door, their olfactory systems tickled by the unusual aroma of waffles.

This monthly underground bass music show called Bass Waffles (where they offer “fat bass and free waffles”) features established as well as up-and-coming bass music DJs from Southern California and are celebrating their year anniversary at the end of February. It could very well be the next Low End Theory—a weekly Los Angeles underground bass, hip hop and experimental music night which shares the same humble beginnings (minus the waffles) and is now a local institution. This flourishing West Coast bass scene is spreading like butter on waffles.

Unlike the four-on-the-floor of house music or the club bangers of EDM that have long dominated Los Angeles’ nightlife, bass music is slower and stranger, taking its listeners on an aural journey through viscous, low end frequencies. The crowd does not bounce as a single organism to a uniform beat like one might experience at a house show. Instead, dancers give each other ample space so they can undulate like rippling kelp without getting tangled in each other’s appendages.

“I really connect to the frequencies and the sonic pressure of bass music,” says Andrea Graham, known as The Librarian, who is also a musical curator and founder of B.C.’s Bass Coast Music Festival. “It’s a physical experience as much as an audio experience. I connect with it on that personal, physical level and then also in sharing that moment with everybody else that is there.”

Bass music—as it’s known in America—is a broad term. But not without nuance. Glitch-hop, dubstep, garage, IDM, temple step, crunk, ambient and beat music are a few that fall under the umbrella of “bass music,” but at the nucleus of all of these categories is a slapping bass so powerful that it hits you in the solar plexus like a sonic cannon.

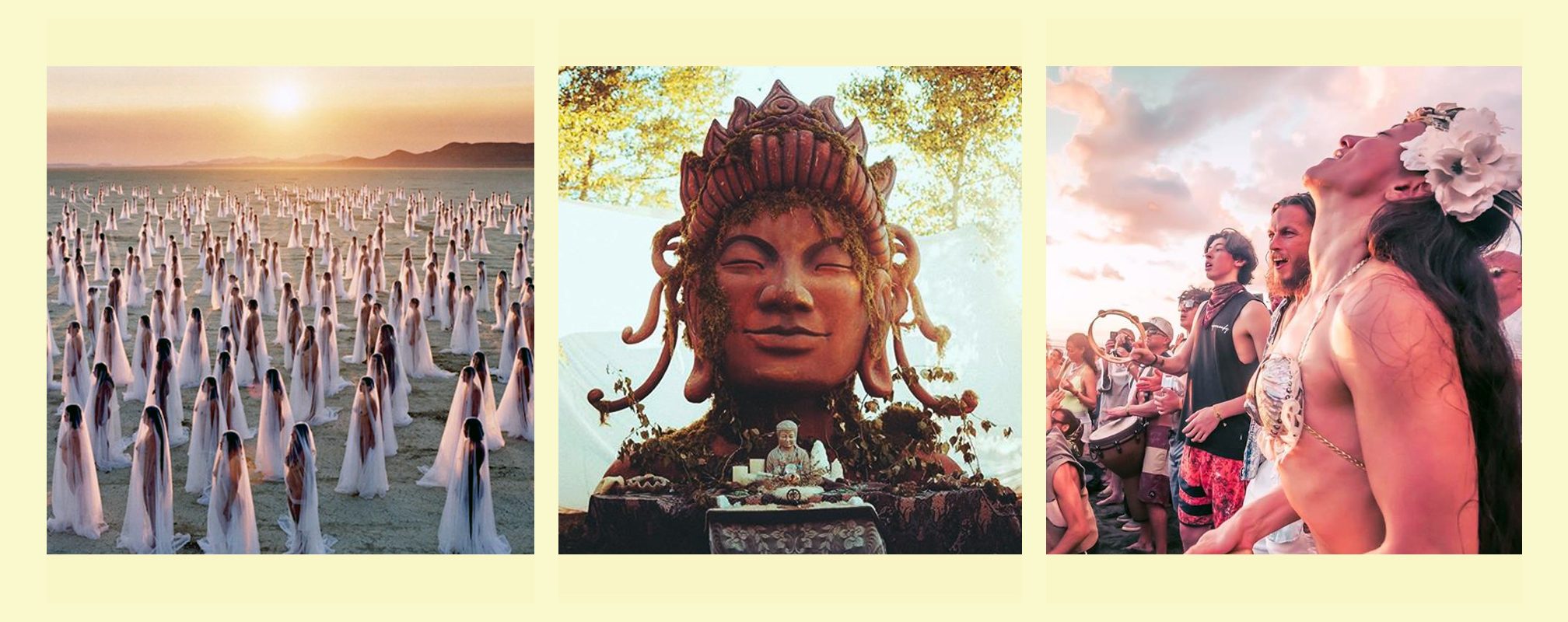

Today, bass music seems like a West Coast fixture because of its pervasiveness in Southern California festival culture and its popularity at Nevada’s annual Burning Man, but its origins come from UK dubstep. Deviating from the high BPMs that eclipsed electronic music in the 1990s, dubstep was a welcomed variation in the electronic Renaissance. When prominent dubstep artists such as Benga, Skream, and Hatcha exploded on the West Coast, stateside artists not only adopted this newfound sound but reshaped it.

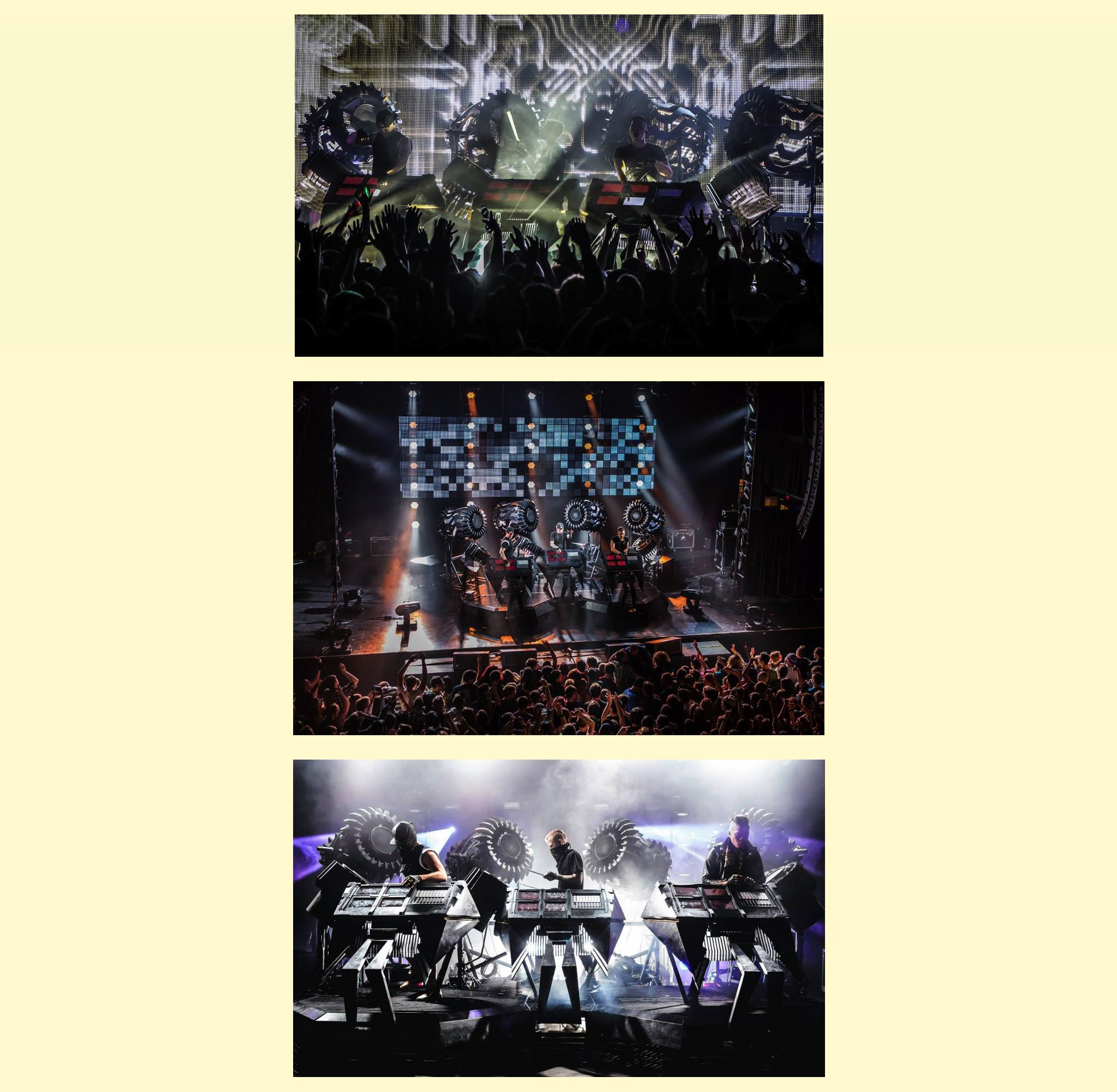

“When we first heard dubstep, we really had our minds blown,” says Justin Boreta, who is one-third of bass music trio, The Glitch Mob. “That was right around the time when Skream and Benga and Hatcha first started playing shows. In a way it was a new sound but it was also familiar because of its roots in dub and dancehall. So we took a page out of the dubstep book and put a big, West Coast, psychedelic slant on the whole thing. Although we never made any typical dubstep, you can hear the influence.”

Formed in 2006 after Boreta, Edward Ma (ediT) and Josh Mayer (Ooah) met at an underground party in Los Angeles, The Glitch Mob began their ascension during the onset of L.A.’s bass music scene. Inspired by the aforementioned dubstep trailblazers and bass messiah Tipper, the trio produced their own pioneering blend of surging dance floor bangers and the type of glitchy, grimy bass-driven music that one might encounter at an underground warehouse party. The Glitch Mob’s success was meteoric as they contributed a new style of electronic music to the percolating scene. They also garnered attention in the industry for performing solely with laptops and MIDI controllers, an uncommon practice at the time.

In this ever-morphing era of technology and laptop music, dubstep has waxed and waned. It saw a peak upon its emergence in the late ‘90s and early 2000s—such as drum ‘n’ bass, techno, house, trap and trance did—and is now kept alive through small cliques who remain loyal to the sound. This is not uncommon in the electronic music world, especially as technology continues to become more affordable and accessible. In an industry that has become so saturated with artists, there is a more urgent need to create music that is unique.

With the help of Burning Man and its celebration of all that is weird and underground, artists such as Tipper, Amon Tobin, Bassnectar, and The Glitch Mob were able to play a role in evolving the sounds of dubstep into our modern perception of bass music. Dripping with psychedelia and originality, its rich, spacey and sometimes bizarre soundscapes are what attracts the festival and Burning Man communities in droves.

“There is something inherently trippy about bass music,” says Boreta. “There is a psychedelic movement on the West Coast that people who make bass music have been more attracted to… For instance, Tipper, who is one of the biggest bass music producers right now, takes you on a journey and it’s larger than life. You can really get lost in it. There’s something about listening to bass music on psychedelics at a festival...that’s why they say that it’s transformational—because people can go there and have a sense of losing oneself.”

The arrival of UK dubstep in conjunction with the West Coast’s roots in psychedelia—Monterey Pop Festival, Summer of Love, the Merry Pranksters, the Grateful Dead, Haight & Ashbury, et al—built the musical foundation of many transformational festivals such as Lightning in a Bottle, Lucidity, Shambhala, and Symbiosis Gathering, proliferating the genre.

Burning Man, the predecessor of the transformational festival scene, was mentioned by Boreta, Mayer and Graham as having a major impact on bass music and its growth. As Burning Man grew in size and popularity, bass music became its dominant soundtrack providing artists such as The Glitch Mob with the seed from which they cultivated their career.

While Southern California has become the epicenter of modern bass music, its influence spans all along the coast and up to Canada. Graham’s aforementioned Bass Coast Music Festival has become a platform for Pacific Northwest and Bay Area bass artists to develop and rise to an international level. Festivals such as Envision in Costa Rica have sprung from the West Coast scene as well, with its main stage featuring an all-bass lineup. The sensual allure of low frequency bass tones seems to be spreading exponentially.

“There’s been a lot of change in bass music over the last 10-12 years,” says Graham. “It went from that rootsier, deeper sound into more aggressive tones for a number of years and then in the last five years, bass music has just opened up and now encompases so many subgenres that it’s really hard to define. There’s the more jungle and half-time influence, the trappier side, that future bass, the digital dancehall and then the psychedelic bass. To me, all of those live under the umbrella of bass music.”

Morena Duwe is a Los Angeles-based journalist, outdoor enthusiast and festival junkie. Read more of her work here.