Features

Features

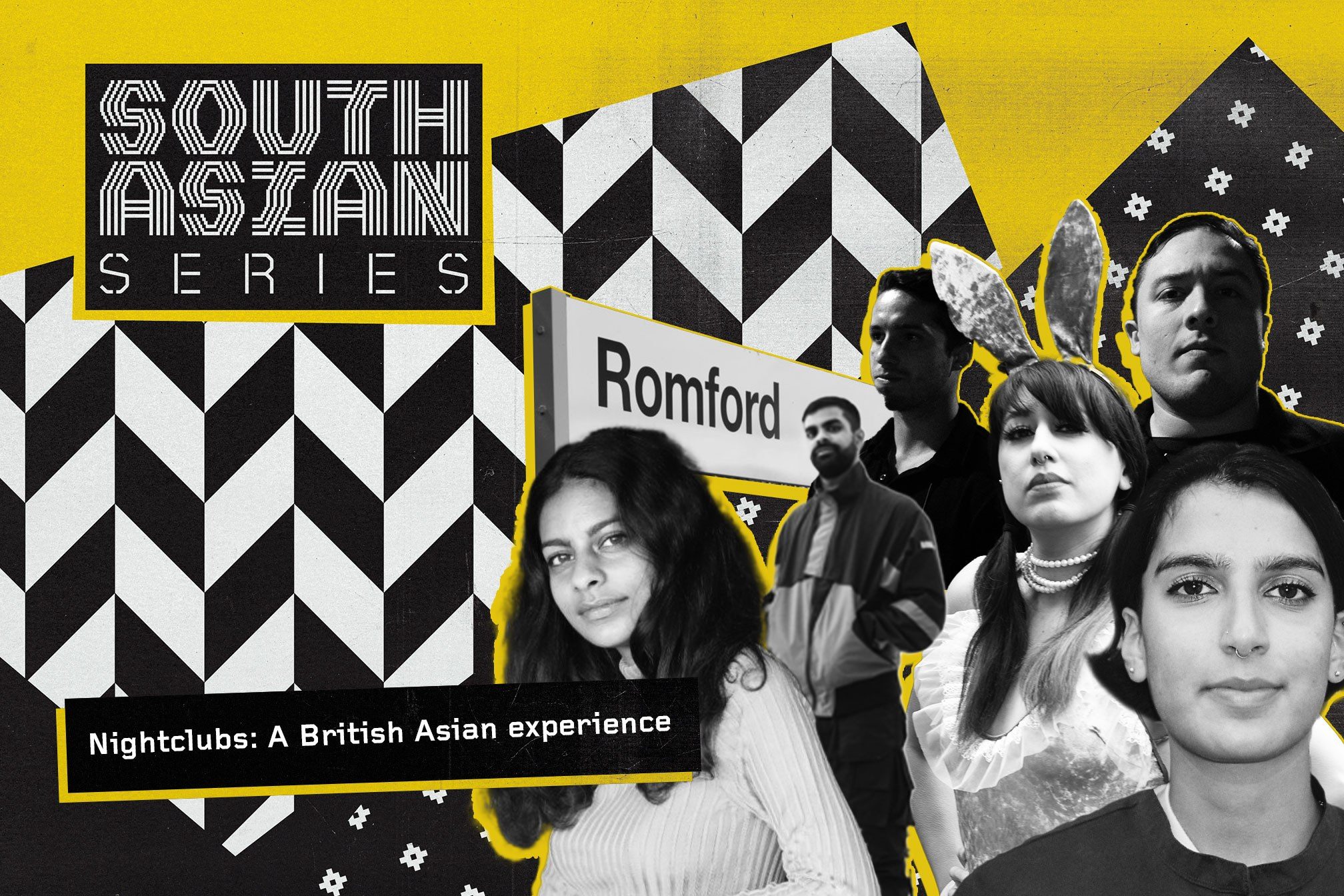

What it's like to go clubbing as a British South Asian person

Across dealings with bouncers, bar staff, promoters, sound engineers and green rooms, Manu Ekanayake examines how South Asian identity affects DJs and clubbers' experience of nightlife

The air was heavy with the scent of B&H (it was the mid-90s), Polo Sport (it was Essex in the mid-90s) and sweat, because the place was rammed. The place was Hollywood’s nightclub in Romford, which I was rapidly realising was a long way from the underground clubs I read about in dance music magazines at the time. But it was as close as my teenage self was going to get. They played the odd house and garage tune, as well as the likes of Whigfield or whatever, but this wasn’t the kind of place you came to lose your inhibitions and be at one with the music. It was the kind of meat market you came to meet the opposite sex after the pub shut and very possibly have a fight. Like most venues in Essex back then, it was also a place where you watched yourself if you weren’t white. But to be honest, I learned to do that in the playground so it wasn’t a big deal to me at the time.

Hollywood’s had a mixed-race door team which was big deal back then and they were known for being tougher than tough. As proved when I saw a lairy skinhead get chinned by a Black bouncer for calling him a ‘fucking Black bastard’. Well, that was what he was trying to say, I assume. He didn’t get further than ‘fucking Black…’ before the doorman threw a hard right which settled the matter. His thick-necked white colleague and I shared a laugh as we watched this play out. As a British Asian from the suburbs I wish every bit of racism I witnessed growing up in the '80s and '90s ended up with a racist being punched. Not even close though, I’m afraid.

Read this next: How Asian Dub Foundation's stand against racism connected generations of British Asians

Because while the '90s saw UK acid house culture explode into a worldwide cultural force, most British Asians were cut off from the clubbing experience. But having conservative immigrant parents who didn’t want their children in nightclubs didn’t stop those kids from wanting to party. I should know as I was one of them. And while Bhangra did nothing for me as I couldn’t understand the lyrics – as a British Sri Lankan who knew only enough Punjabi to know when he was being insulted – it was the root of what would become the Asian Underground, the first British Asian movement in British clubbing history. This cross pollination of Western and Indian subcontinental music was at its most vibrant at Bhangra ‘daytimers’. These were day-time events where British Asian teens could party with their peers, with different genders and religious groups mixing readily, all during school hours. So by bunking off sport on a weekday afternoon and packing a change of clothes they could still get home for dinner. That was the idea, anyway.

Riz Ahmed’s film Daytimers really gives a flavour of these events, which I heard about through friends who had more access to London. It was the mixing of genres, for young crowds who loved hip hop, jungle and garage as much as they loved Bhangra – which is itself the sound of Punjabi folk music mixed with Western pop influences by the British Punjabi diaspora – that led directly to the merging of Eastern and Western influences that would become known as the Asian Underground.

Read this next: A potted history of the 1990s British (South) Asian Underground

This new scene was made up of artists who had grown up British, but their music was a combination of Western influences and the music of their South Asian immigrant families. Producers like Nitin Sawhney and Talvin Singh mixed tablas (twin Indian hand drums) with electronic basslines and sitars (stringed instruments) with saxophone, as the energy of punk and the creativity of second generation immigrants morphed into a many-splintered musical movement. The likes of Bollywood remixer Bally Sagoo and rapper Apache Indian – both from Birmingham – made it into the charts, while Fun-Da-Mental fired out fiery political raps, Asian Dub Foundation mixed Indian classical music and synths. and contemporary radio mainstays like Bobby Friction and Nihal Arthanayake (my fellow Sri Lankan) got their start. It was a benchmark moment for British Asian music culture. And even if the movement didn’t last much into the 2000s, Panjabi MC’s ‘Mundian To Bach Ke’ aka ‘Beware Of The Boys’ ft. Jay-Z is still a fine example of how much cultures were meeting thanks to this movement.

Today there’s a new South Asian movement underway in clubland, which is again led by Daytimers. But this time the South Asian collective leading the charge is actually called Daytimers, in tribute to those seminal late 80s / 90s British Asian parties. If you’re reading this you’ve probably seen their Boiler Room appearance ahead of Dialled In festival. Needless to say, they shelled it down. But when I spoke to Daytimers internal team member Riva for this piece, she shared a less joyful memory about an early nightclub experience.

“When I first moved to the UK for uni from the Middle East, where I grew up between Dubai and Saudi, I went to a very posh club in Mayfair,” Riva, who is British Indian, tells me. “It was 2014, I was 18 and I was just discovering alcohol, as someone who didn’t grow up around it. And I just went completely over the limit in how much I drank. So I ended up in an alleyway outside and got beaten up by the security guard. I mean my face was fucked up! It was ruined for like a month and I could not go anywhere because I looked so bad...

Read this next: 10 South Asian diaspora dance music collectives you need to know

“The problem was that I was so intoxicated that I thought I'd walked into something,” Riva remembers. “So after that I realised that I needed to be much more careful – and also that I couldn’t rely on those friends, which was a bit shit obviously. But here I was in the 'best' part of London and I was there because a friend wanted to go, as I'd never have usually gone somewhere like that. I felt like I'd done something wrong. Coming from a culture where alcohol is considered taboo, I thought that was what I'd done was wrong so in a sense I'd deserved it.”

In retrospect, upcoming techno talent Riva is able to see the root cause of this harrowing episode. “It’s power dynamics really, isn't it? Back when I was promoting at uni in the Midlands, not so much with security but with promoters, I'd always have such weird experiences. Because the idea you have power over someone else, especially as a man over a woman, can lead to people being able to cross as many lines as you want, hiding behind the veneer of intoxication.”

Anu, an established British Indian DJ and NTS Radio regular, also had a few words to say about promoters. “There have been many times when I'm sitting at a DJ dinner and no one's really talking to me and no one feels comfortable with my presence; I can feel it. That's when I know I’m the token booking. I mean I've been at dinners where the DJ has introduced themselves to everyone else at the table and just missed me out. They probably think I'm someone’s girlfriend. And there have also have been occasions where, a few years ago when my profile was not what it is now, I have been left to my own devices before a gig. Now I know that this will happen but still, the way I've done things as a promoter is that you treat everyone the same, you give everyone the same 'service', as it were. I've got to gigs and had to turn on all the equipment myself. Or gotten there and there's incredibly misogynistic labels on the mixer. One gig I remember very well it said on the mixer: 'Red lining is for prostitutes.'”

This brings us into the realm of sound engineers, the legendarily bad-tempered guys (and it is usually guys) you’ll often find looking annoyed as the DJ pushes ‘their’ soundsystem into the red. Anu had a few more memories to share, “I feel a lot of the time they look at you like you don't know what you're doing and they are very willing to just come in and change something mid-set and completely throw me off. There's not much respect there.

“And there have been numerous occasions when I've had a male friend with me and they'll be chatting away to them and I have to be like 'Hi I'm DJing here today, nice to meet you' yet they've already told my mate their life story” Anu continues. “So sometimes you look inside yourself and wonder if you're just an unapproachable person. But it's actually not that. It's their personal shit.”

Read this next: Exploring identity: What does it mean to be a South Asian in the UK in 2021?

Now by this point in your night out you’ll probably want a drink, so let’s go to the bar. Here being Brown can be either an overt or a covert hindrance to your night out. Bill Rah is 23-year-old a Scottish Pakistani DJ and journalist from Glasgow, who runs the Behind The Decks platform. He remembers one incident vividly. “It was a couple of years back at [Edinburgh club] Cabaret Voltaire. And what had always just been weird looks and attitude from this one barman spouted over one night over the bar during the [Fringe] Festival. Now as he walked away he used a racial slur to describe me, while the bar’s assistant manager just looked on. I got thrown out for having a go at him because of this though. I was pretty gone; I wasn’t going to let it go, no way. Then I heard I was banned for life. So I gave it a wide for a while, obviously. But eventually I went back after the FLY Open Air [festival], me and my pal. We paid in, no problems at all. But then that same assistant manager was there and she started screaming at me and then the general manager, so her boss, grabs me and drags me outside and throws me onto the pavement and roughs me up a bit while telling me never, ever to return. I’ve since been told my ban’s been lifted, but why would I ever want to go back?”

So sticking up for yourself while brown can sometimes be a dangerous business. But often racism isn’t so obvious. Rachael Williams is the booker of Rye Wax in Peckham, as well as DJing as Ambient Babestation Meltdown. She remembers her experiences clubbing in Shoreditch in the early 2000s as a mixed-race woman (she identifies as Anglo-Indian and Anglo-Burmese) at a time when it was more about what we now call racial gaslighting. “The thing is for someone who’s probably white passing, at least when the lights are low in the rave, I’m not going to have those out and out racist experiences; it will be more subtle than that. I think if we look at the early 2000s, then people were treating me differently in a way that was hard to pin down. Because I think it was matter of not getting served quickly because I wasn't the 'cute' blonde girl, for example. So the barman is going to serve all the girls like that and then you'll be left at the end if you’re lucky and you can't call them out on it. Like you want to say something but you can't, because you don't trust yourself because you've been taught that it's all in your head. Now if you have a bar with four white barmen back then, all four would have been acting like that. Now it's maybe one.”

Read this next: What Do Your Parents Think?: 4 South Asian DJs share their family's reception to a music career

So now you’ve had a few drinks, you run into a well-connected friend and get invited backstage to the Green Room. Now you’ll get to see how it all works from the inside, right? Well, maybe. Just don’t expect an easy ride back there. As Rachael says, “All the clubs big enough to have proper Green Rooms are likely very, very white backstage. And while I think it’s getting better – like at the Don’t Be Afraid birthday at Corsica Studios, I saw loads of POC there – while line-ups are still very white. it’s not going to change too much.”

Anu agrees, “Backstage can often be quite chill. But you know there have been occasions where I did feel othered. I think it's more people thinking that you're not cool enough to interact with. People not believing that you're cool enough to be a DJ. And a lot of that comes down to just being South Asian. I don't know... white people just don't think we're cool. And we're just so used to experiencing that, it's very easy to tell when that's what's going through someone's mind. I think especially in those kinds of spaces where clout is very important, like are you cool enough to chat to, that kind of thing is really the case.”

Ahad Elley aka Ahadadream, 31, a British Pakistani DJ who also runs More Time Records and whose No ID event is co-promoting Dialled-In, echoes Anu’s point about how South Asians are perceived, in club spaces and in general. “One thing I think we have to talk about is that no one thinks you’re gonna be the DJ. This has happened to me recently. Like they’ll say ‘You seem so quiet and unassuming then you just shelled the place down when you played. I didn’t expect that.’ That’s the perception we have to change.”

To conclude – let’s call this the deep chat at the afters part of the evening – I can only agree with Ahad. My 16-year-long career in music journalism has had its own share of ‘Where are you from? No, where are you really from?’ low-level racism, but I can count the amount of obvious racist behaviour on the fingers of one hand. But still, after spending a week talking to my fellow Brown clubland professionals, I can’t help but feel that I’ve had a harder time at the rave coalface than I should have. I’m out there trying to look non-threatening when I queue up outside, for years I shaved before a night out lest I look too much like the Daily Mail’s idea of a terrorist and I always wanted to be on some kind of list, because I knew I didn’t ‘look the type’ to enjoy electronic music – I know this because I’ve had door staff say it to my face. Now we all carry our own range of issues around with us whenever we go out, but I’m sure that in 2021 being Brown shouldn’t be one of them. I can only hope that with more Brown people being involved in London nightlife professionally and collectives like Daytimers driving forward with events like Dialled In that showcase South Asian talent, the next generation of Brown clubbers will feel more like acid house’s much vaunted ethos of inclusion and equality applies to them too.

Manu Ekanayake is a freelance writer, follow him on Twitter