Features

Features

Mysteries of the deep: How Drexciya reimagined slavery to create an afrofuturist utopia

Marcus Barnes presents the history of Drexciya, the mysterious Detroit duo who built their own vast underwater afrofuturist utopia

“Love each other, love the music and go for it, whatever your heart desires,” is how Drexciya founder James Stinson signs off on his last ever interview. The now legendary 27-minute long recording, hosted by Liz Warner (then Copeland) on WDET-FM in Detroit, is one tiny piece of a far larger puzzle that makes up the Drexciya legacy. James Stinson, one half of the act, died on September 3 2002 at the age of 32. His partner Gerald Donald has continued to make music under a dizzying array of aliases, though the Drexciya project effectively ended with Stinson’s demise. “All experiments must continue, even until death,” Stinson says during the interview, a statement of intent fueled by what seemed to be a deeply ingrained desire to extract the music inside his soul and get it out there in its purest form, untainted by the world outside his studio.

28 years since the duo’s first release, ‘Deep Sea Dweller’, appeared on Shockwave Records (a sub-label of Underground Resistance) Drexciya possess one of the most timeless and intriguing legacies in electronic music. Fans all over the world have been consumed and mystified by the science-fiction fantasy and mythology since the project’s earliest releases, with themes connected to water present in pretty much everything they did up until their last album ‘Grava 4’, which turns the focus skywards, up to the cosmos. The mystery and intrigue is compounded by the fact that, in their entire 10-year run, neither Stinson nor Donald ever personally laid down a definitive manifesto or storyboard for what Drexciya was all about. This in part keeps the legacy alive, with fans new and old conjuring up speculative theories and hypotheses relating to the origins and ideologies behind what the two men were doing. They were enigmatic and rarely gave interviews, Stinson’s WDET-FM appearance was among the very few to have taken place, both men keeping their identities anonymous. In the pre-Internet mid-1990s Drexciya maintained their shadowy identities with relative ease. The music they made was radical, raw and heartfelt, yet soulful, pure, undiluted, full of funk and alive with energy. In its day it was totally fresh and unique and even now it stands out on its own as the soundtrack to another world, the underwater world of the Drexciyans.

It’s believed James Stinson and Gerald Donald went to the same school in Detroit, Stinson became a mentor of sorts to Donald who was a few years younger. “He took Gerald under his wing, they just hit it off and he stayed with us for months,” his mother Helen Stinson says in an interview on YouTube. “James was more in the father type of position with Gerald.” The two men would spend hours in the studio together in the basement of Stinson’s mum’s house. A strict no-access policy meant no one could enter the studio, especially when they were at work, even his mother. According to Kodwo Eshun, a British-Ghanaian writer and academic whose fascination with Drexciya has featured in his past essays, Stinson and Donald “used to imagine themselves in a submersible descending to the bottom of the ocean, the absolute depths of the Mariana Trenches – absolute silence, blackness, crushing pressure, the creaking of metal. He said that they would think themselves into this space and then they would start making music from this perspective of insulation and isolation.” Eshun spent four days with Gerald Donald during the making of his Drexciya-inspired film Hydra Decapita, released in 2010, and was only permitted to record Donald when he responded to track titles read out to him. The Mariana Trench, in the Pacific Ocean, is one of the deepest trenches in the world. With this rarely explored environment as their inspiration, it’s hardly surprising that their music feels so otherworldly. They transform an inhospitable environment into their home and from that base they create music that breaks free from surface level geo-normative constraints.

Water is the overarching theme throughout Drexciya’s discography. Take a quick glance at the titles of their tracks and you’ll find a long list of references not only to the sea and waves, but to imaginary elements such as the aquazone, Bubble Metropolis, Andreaen Sand Dunes, Digital Tsunami, Darthouven Fish Men and so on. Stinson talks at length about his aquatic fascination in two of the interviews he did months before he passed away. He describes water as “the most powerful element on this planet” which “gives us our own territory, where you can be isolated and go on with your daily business and not really be involved. It’s like an isolated community and it’s more peaceful... There’s a lot of areas we haven’t discovered yet.” This preoccupation with water underpins everything Drexciya did. The music itself often sounds saturated, it percolates with energy, pads wash over you, synth lines squelch and appear soggy in places, there’s ambience and serenity, violent stabs, crashing percussion. Stinson wanted his music to mimic the ‘personality’ of water: universal, adaptable and able to take on any form or mood. “We float with the current,” he said in an interview with Andrew Duke in 1999, explaining that they go with the flow and create music how and when they please. For the Drexciyans water was their saviour. Water is home, it’s where they bask in solitude away from the evils of humanity. But water is also a threat, it can lash out viciously during a storm and destroy. Not long before Stinson died, Drexciya produced the Seven Storms, a series of seven albums under various guises, all focused on different moods, created during what he described as a turbulent year. Water is the origin of life on Earth, no living being can survive without it. Drexciya salute its universal power with their music.

The Black Atlantis

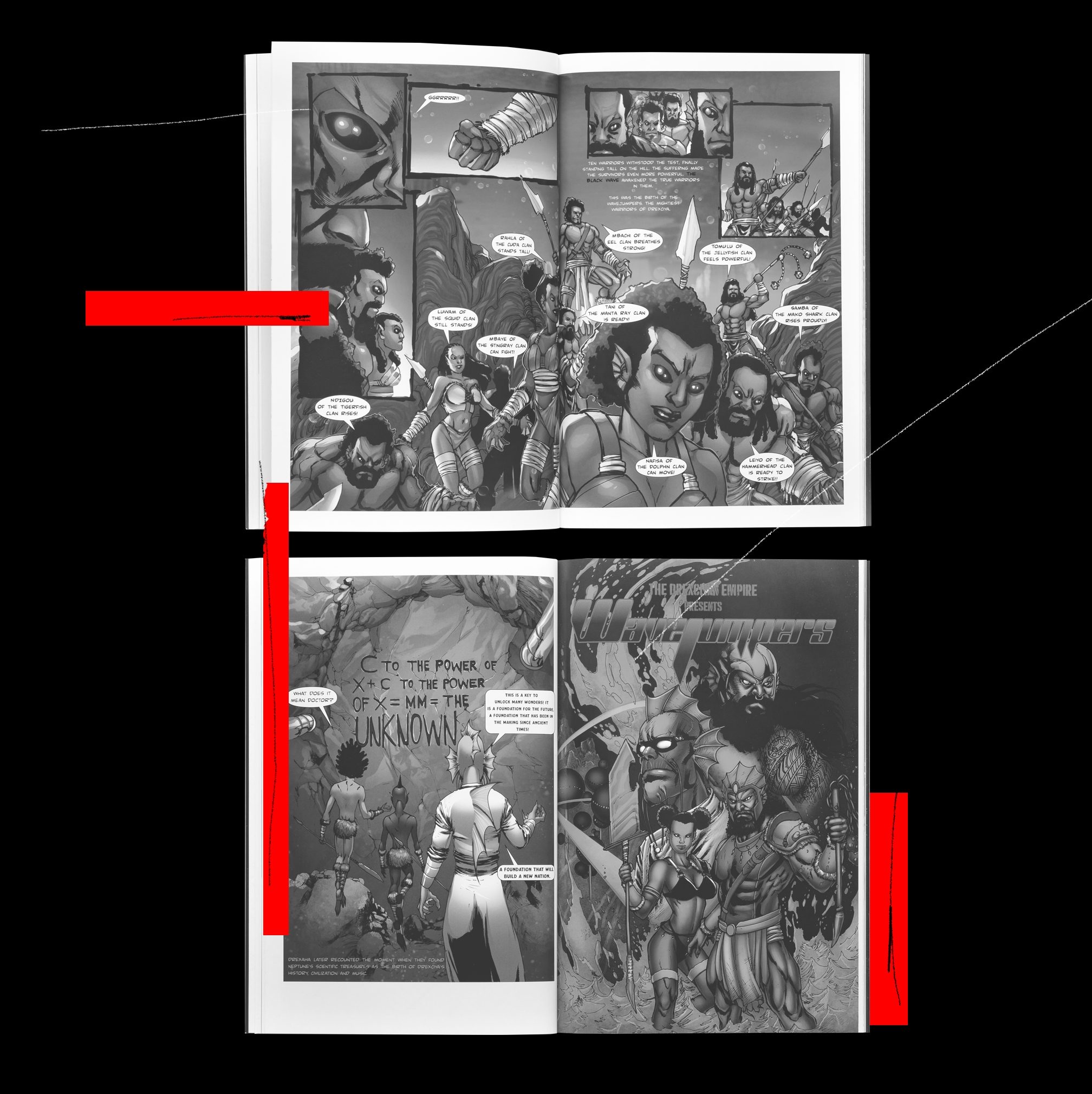

Around the central aquatic theme they built an entire world, with track names illustrating characters and locations from this alternate universe, several leagues below sea level. Keen fans attempted to piece together the Drexciyan world by using those track titles and sporadic vocal snippets in the tunes themselves. Throughout their releases Stinson and Donald presented a variety of clues and hints about the world they created (and operated in), sometimes in collaboration with Cornelius Harris (AKA The Unknown Writer) and Mad Mike from Underground Resistance. For Instance, their 1995 EP ‘Aquatic Invasion’ includes the text: “On February First Nineteen Hundred And Ninety Five the Drexciyan Tactical Seaforces received orders from UR Strikeforce Command, for one final mission. The dreaded Drexciya stingray and barracuda battalions were dispatched from the Bermuda Triangle. Their search and destroy mission to be carried out during the Winter Equinox of 1995 against the programmer strongholds. During their return journey home to the invisible city one final mighty blow will be dealt to the programmers. Aquatic knowledge for those who know.” Penned by The Unknown Writer, who was a familiar voice at the UR HQ. Perhaps not a direct message from Stinson and Donald, but nonetheless it would’ve at least been discussed and subsequently given the green light by both men. ‘Aquatic Invasion’ also introduced fans to the first true visual representation of characters from their world. The striking image of two ‘Drexciyan Wavejumper Commandos’ was the first peek into the shadowy, marine world that is Drexciya.

By creating an entire world of their own, Drexciya were able to let their imaginations run wild which is why their music is so unique. In their minds they really were Drexciyans living under the water and making music to heal the planet. “I don’t just want to ride the image of a place, or an attitude or personality,” Stinson said. “I wanted to do something that involved a total concept and take people somewhere else instead of giving them the same thing they see every single day when they step outside their door.” The deeper they explored and challenged the boundaries of their own imaginations, the more this world expanded and the more their music evolved to attain its own characteristics. This was amplified by Stinson’s decision to operate in total isolation, avoiding other peoples’ music and going out to clubs so he had a staunch, singular focus on Drexciya. “I don’t enjoy myself, I don’t go out to clubs or anything because I’m dedicated to what I do,” he told Liz Warner. “It’s almost like a phobia, if I go out I’m going to pick something up. I don’t want it to come inside my music and make it impure.”

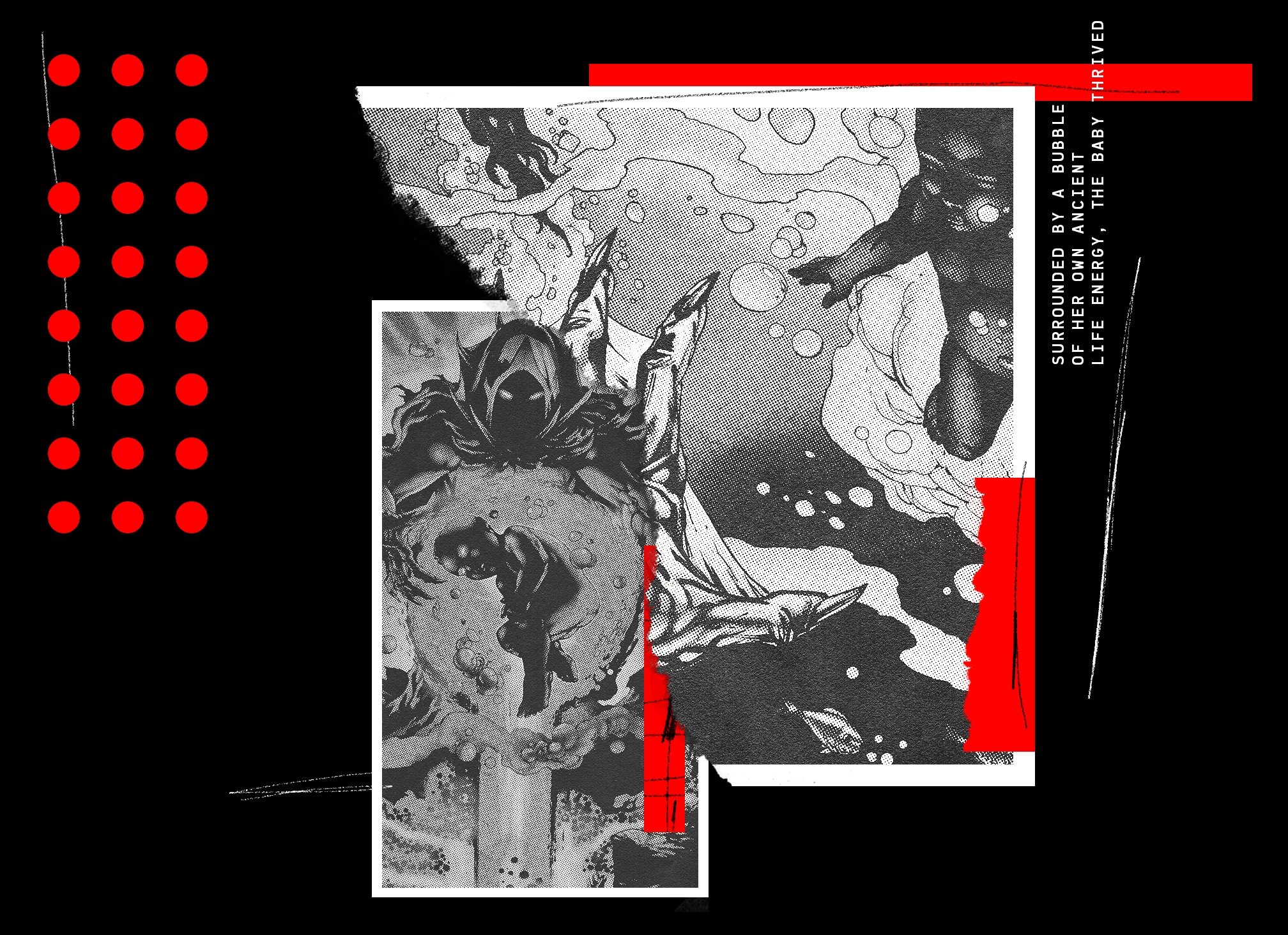

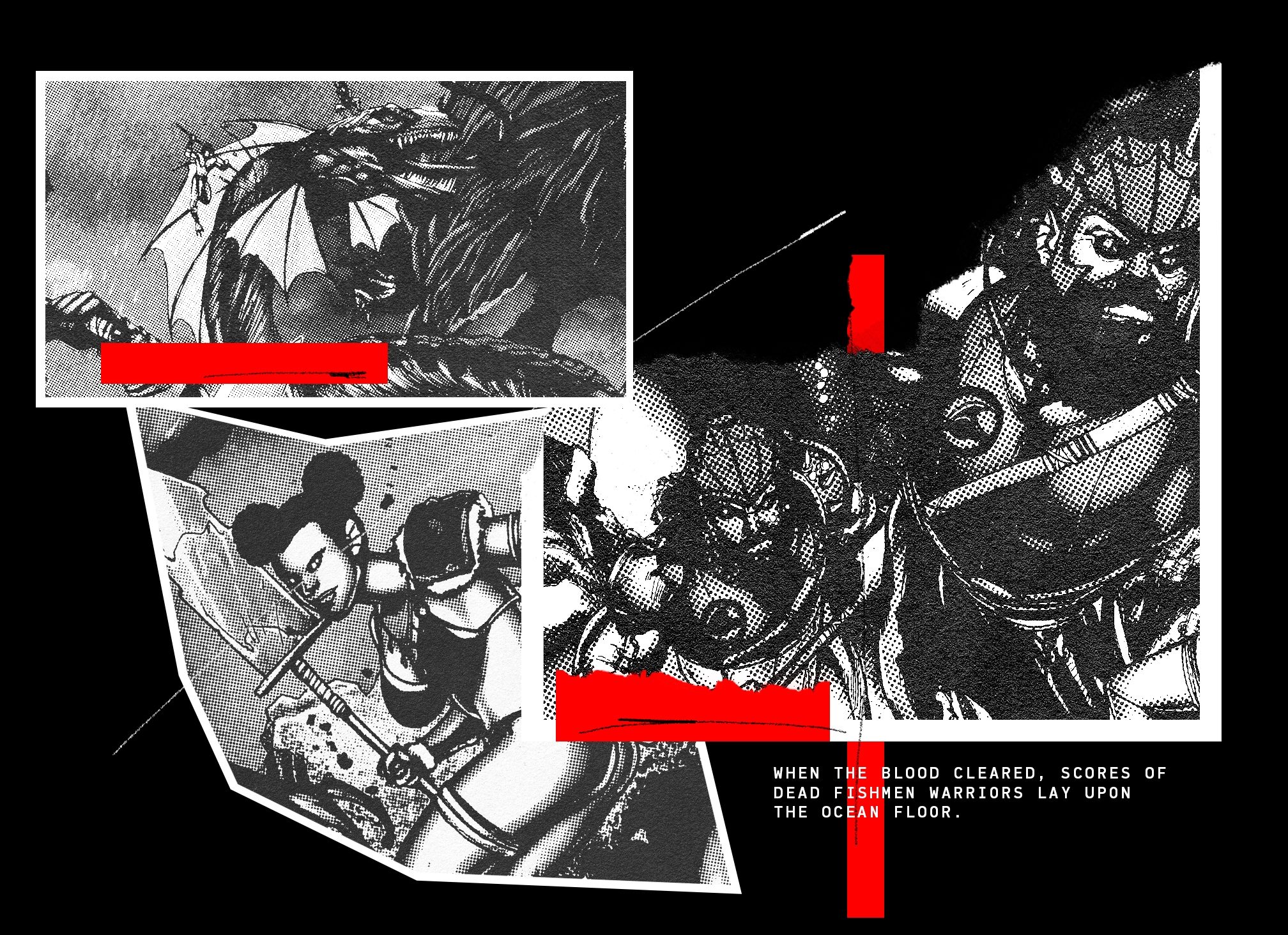

Immersing themselves in their own underwater ‘Bubble Metropolis’ allowed Stinson and Donald to cultivate an escapist audio fantasy firmly rooted in the horrific reality of world history. The roots of the most popular hypothesis regarding the Drexciya myth can be found in the liner notes of ‘The Quest’, a 1997 release which, again, features a message from ‘The Unknown Writer’. This release featured the most explicit revelations of the Drexciya catalogue so far, with thought-provoking questions and statements such as “Could it be possible for humans to breathe underwater? A foetus in its mother’s womb is certainly alive in an aquatic environment. During the greatest holocaust the world has ever known, pregnant America-bound African slaves were thrown overboard by the thousands during labour for being sick and disruptive cargo. Is it possible that they could have given birth at sea to babies that never needed air?”. The notion is that pregnant women thrown overboard during a slave ship’s journey through the infamous Middle Passage could have birthed amphibious offspring that went on to establish an underwater world. Throughout the sleeve notes The Unknown Writer asks questions that are never actually answered - in fact, he closes by saying, “These are many of the questions that you don’t know and never will.” However, it remains a key transcript in the Drexciya myth and one which is commonly accepted as the origin story behind it all. The text is accompanied by a series of maps of the world and North America, each with its own title and each featuring a different diagram. The simple cartographic illustrations add another dimension to the words from The Unknown Writer. We see ‘The Slave Trade (1655 - 1857)’, ‘Migration Route of Rural Blacks to Northern Cities (1930s - 1940s)’, ‘Techno Leaves Detroit Spreads Worldwide (1988)’ and ‘The Journey Home (Future)’. All of which serve as a poignant reminder of the roots of techno, a genre, like many others, that is the result of the forced repatriation of Africans in the 200+ years that the abhorrent slave trade was in operation. Neither Stinson nor Donald ever publicly commented on this, though when questioned about their work connecting to the lineage of afrofuturism, in a 2013 interview with Electronic Beats, Gerald Donald took the opportunity to state, “I do not wish to specify any particular ethnicity. I would state that all variations of humanity have contributed to the evolution of electronic music.”

What do you feel?

“When I was discovering them it was the mythology,” says Stephen Rennicks, the man behind Drexciya Research Lab, a long-running blog and Facebook page where he collates information and posts content related to Drexciya and the project’s many offshoots. “Someone told me about this mythological underwater civilisation and that got me interested. That is the key for a lot of people, it’s an entry point that piques their interest and sucks them in. Also you couldn’t go and see them play live, you couldn’t see them DJ.” Even today, there are just a couple of images of James Stinson on the web. In an age where fans have access to a huge online library of images of their favourite performer, many of which offer personal insight into their lives - their home, their studio, their children, what they had for breakfast and so on - it’s incredible to think that Stinson did such a thorough job on cloaking his identity. “I have my own personal interpretation… that’s the beautiful thing, everyone has their own interpretation,” says Rennicks, speaking further about the mythology. “For me it’s the idea of finding your true self somehow. Submerging, going deep into your subconscious would be a metaphor for the underwater stuff. And ‘Don’t Be Afraid of Evolution’ was a title they used towards the end of the Storm Series, so there’s the idea of self-evolution.”

There are many leagues to the symbolism behind their work, it’s up to you how far you want to go with it, something that Stinson encouraged. “It’s not for me to say, it’s up to the listener. It’s the same way it’s been from day one with all the Drexciya music,” he told Liz Warner in 2002, speaking about the meaning behind the Storm Series. “I can come out and say, ‘This is what it is, this is my intent’. Ok well, what if that person’s listening to the record and that’s not what they feel, that’s not what they see?”

“So I do like I have from day one, I don’t say anything about it,” he adds. “You listen to it, you tell me: what do you feel? That’s the way I made it, it came out of me, it came out of my partner, from our soul, we dug it out of there in one take. It’s a masterpiece, it’s a work of art and the energy is captured. And whatever energy is projected, capture it and see what you feel.” Pressed further on the true theme behind Drexciya, his response was profound and remains one of the most enduring quotes attributed to them. “An infinite journey through inner space, the space within and find the beauty inside,” he stated. Ambiguous yet emphatic, just like their music.

There Are Only Two Wavejumpers In Existence Today

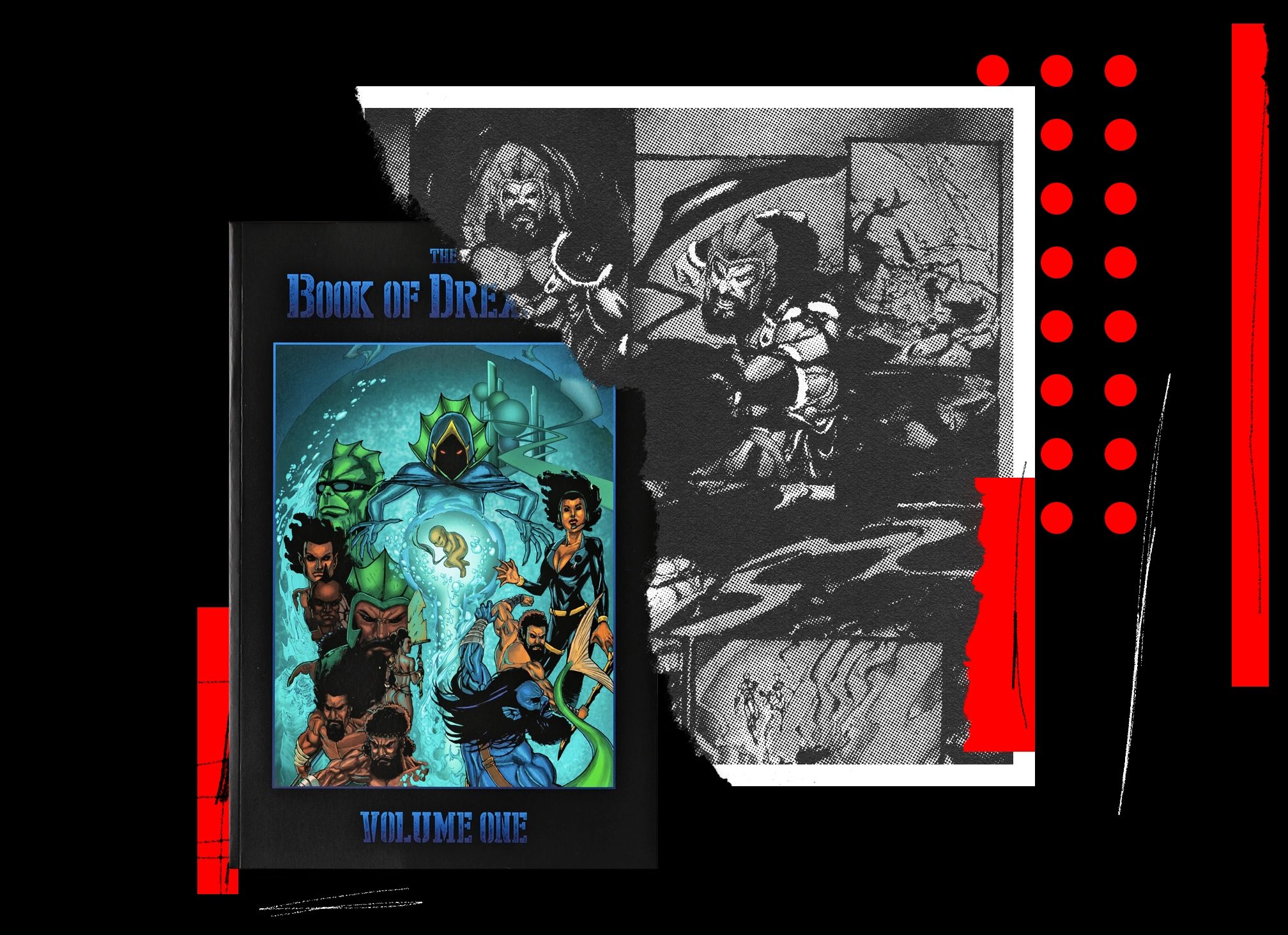

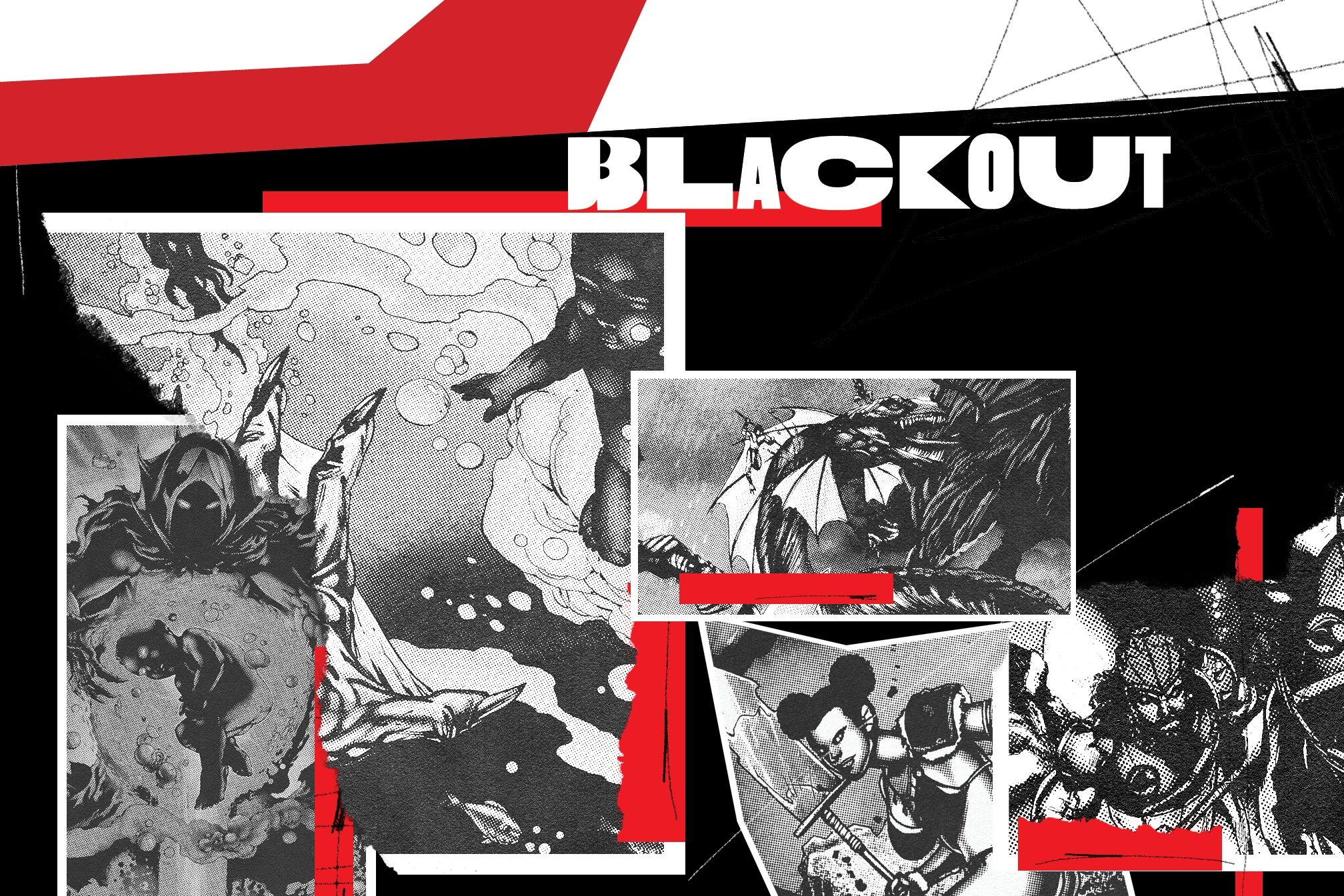

“I believe James himself was something of a science-fiction genius,” says Abdul Qadim Haqq (AKA Surface World Scribe for the Empire: Agent Q149-13), the artist behind graphic novel The Book Of Drexciya: Volume 1. Haqq worked closely with Drexciya on the album art for ‘Neptune’s Lair’, released in 1999, conceiving and developing imagery that depicted various Drexciyan commandos, plus their assault vehicles and the Bubble Metropolis itself. Now the graphic novel is set to tell the story of the Drexciyans from the very beginning. “I have been able to visualise pretty much the whole story of Drexciya. It’s a story that should be told,” he adds. Abdul’s book will be the first in a series of novels that reveal more about the Drexciya story, as told to him by Stinson in their meetings back in the late nineties. Besides offering more insight into the story, he is also hopeful the book will connect the black community to Drexciya’s music and the mythology, perhaps offering healing as it depicts the Drexciyans in all their majesty.

“I hope it will help black people to relate to these songs and these stories in some way,” he says. “I also hope it will help them to deal with some of the unconscious things relating to slavery. It’s an important project for that kind of direction. It’s a positive thing, it’s positive for everybody.”

“There are many messages,” he adds. “But one of the main messages is, ‘coming from the humblest of beginnings, where you’re almost wiped out, then overcoming that and improving yourself, making yourself into the greatest person you can be. Facing all of life’s challenges and being the best human being to yourself and your community’. It’s about people coming together and unifying.”

Drexciya’s music has been released on several key labels over the past couple of decades. They include Aphex Twin’s Rephlex, Tresor, Warp and, more recently, Clone. The Dutch label has secured several reissues and previously unreleased material from Stinson and Gerald under different guises, put out via the Aqualung series, as well as a huge reissue collection entitled ‘Journey of the Deep Sea Dweller I - IV’. This is what Stinson referred to as ‘Wave jumping’, utilising various platforms to get their transmissions out there. “He explained the Drexciyans to me, it was important so that we could understand the project and the artwork,” says Carola Stroiber, former A&R at Tresor. She met Stinson in the nineties when she signed the albums ‘Neptune’s Lair’ and ‘Harnessed The Storm’. In keeping with the water theme she was taken on a fishing trip to Detroit’s Belle Isle by Stinson when they first met. “He said the Drexciyans are fighting for peace and the good things in the world. It was not just a story that was made up to be important or to have a pitch to the press, or an angle to talk about,” she adds. “It was based in truth and the whole thing could not happen without this idea.”

“The mission was to reach people who understand and feel the music,” she continues. “It was not done to become famous or make a lot of money, or to go out and play a lot. What he told me was that it comes out of his stomach and mind when he goes into the studio, and it has to come out.”

What’s clear from all that we know about Drexciya is that James Stinson had a pure hearted intention with their music. It came from an honest place that paid respects to Black history and aimed to connect with anyone who ‘got it’. Emotions are timeless and, because of this, Drexciya’s legacy is eternal. You can lose yourself attempting to decipher the hidden meanings or lose your inhibitions and simply feel what they were communicating through their productions. “If you make music because you love it and because it’s in your blood,” Stinson told Andrew Duke in his 1999 interview, “I think you’re going to make some of the most beautiful things that anybody has ever heard.”

The Book Of Drexciya Vol 1 is out now

Crowdfunding for The Book Of Drexciya Vol 2 has begun

Marcus Barnes is a freelance journalist and regular contributor to Mixmag. Follow him on Twitter