Features

Features

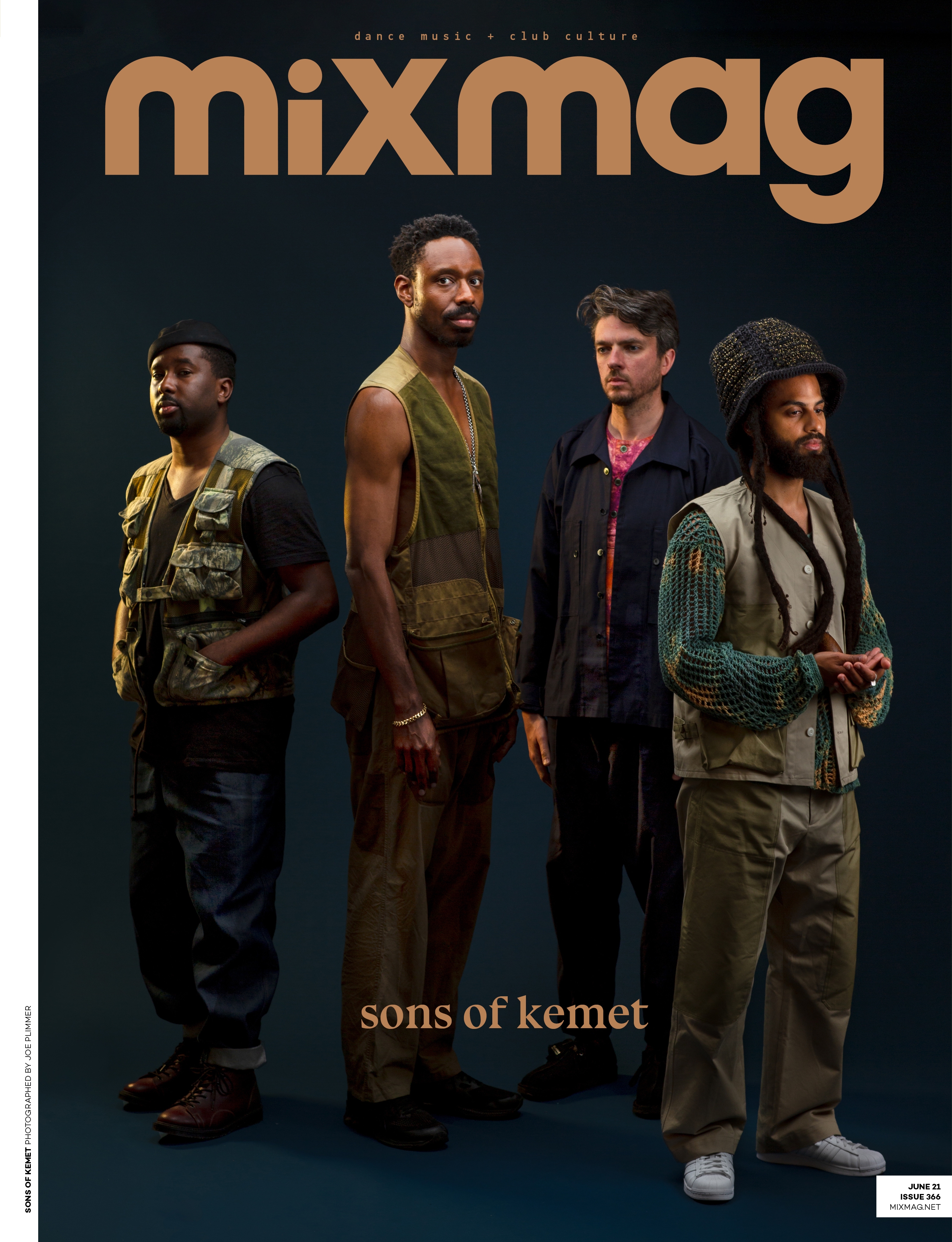

Transferring energy into sound: Sons of Kemet make jazz a vessel for spiritual exploration

Haseeb Iqbal speaks to band leader Shabaka Hutchings about free expression, the transcendent headspace of performance and their poetic new album 'Black To The Future'

“All the practice and research I have done is about creating a body and a mind that is able to transfer energy into sound,” says Shabaka Hutchings, the saxophonist, clarinettist, flautist and all-round artistic virtuoso who has been a driving force amidst the jazz landscape for the last decade, both within the UK and across the globe. One of the country’s most occupied and impactful contemporary musicians, Hutchings’ latest work comes in the form of the new album from British jazz outfit Sons of Kemet - one of three bands that he leads alongside Shabaka and the Ancestors and The Comet Is Coming, all of whom are signed to the seminal jazz label, Impulse! Records.

Sons of Kemet's new album ‘Black To The Future’ is a simultaneously hard-hitting yet politically introspective piece of work that adopts the template of a sonic poem. Like everything that Hutchings creates, there is a poetic depth within this record that requires a patience from the listener, as the music urges us to both observe and reflect on the complexity of its meaning.

Read this next: Shabaka Hutchings: "Style is a part of jazz. You associate a sharpness with the word"

For a band who have built their identity through their distinct, instrumental-focused sound, their latest work incorporates more vocals than any of their previous releases, featuring the likes of D Double E, Kojey Radical, Lianne La Havas, Joshua Idehen and Moor Mother. The importance of poetry on the record’s journey becomes clear, as Shabaka explains what message he sought to express via the music.

“The concept emerged as the piece emerged. I could say that there was a concept right at the beginning but I’ve realised it doesn’t work like that for a reason. It works that we try to get the music out in a way that is as pure and intuitive as possible,” Shabaka tells me with an ease and excitement via a video call from his South London home. “The resounding feeling when I look back at what I was interested in, or concerned about, when making the record was: trying to look at what it really means to have an African-centred worldview.” He unpacks the phrase ‘African-centred worldview’, explaining that he wanted to create something that provoked “ways of seeing that are non-Western" in the wake of George Floyd’s murder and the subsequent Black Lives Matter protests.

A key part of entering this headspace was allowing his fellow band members to operate on a similar frequency. Accompanied by Theon Cross on tuba and both Tom Skinner and Eddie Nache on drums, the group would undertake certain exercises during the creation of this record to try and access those alternative perspectives.

"For example, in the studio we would play tunes for longer, so that we are able to get out of our individual relationships with the material and rather get into a space where we are all operating as one entity. If you play a tune for half an hour, repeatedly, there will come a point where you lose yourself and your sense of an individual, and you get into what the sound is doing as a collective. And that is how we tried to structure each of the tunes. We played them for a really long period of time, so that we could enter this collective headspace in the making of the album. That’s one of the ways an African worldview or ontological idea really made us alter the way we approached our recording session. And that’s at the basis of what the album is about – it's about the fact that we need to look for those ways of looking and seeing. That comes from those traditional African ontologies and seeing how we can apply them to our activities,” he explains.

For Sons of Kemet, exploring these alternative and important histories, outlooks and attitudes through their music is not a new thing. Their prolific, Mercury-nominated, 2018 record, ‘Your Queen Is A Reptile’ harnesses a similar template, outlining nine influential Black women throughout history and introducing them on each track as their queens. Shabaka reflects on the similarities between the records: “These women represent us in terms of what a leader should be. It was trying to start a conversation about leaders. We are going to call your queen a reptile. Can you tell us who your queen is in light of the queens who we have set out? 'Black To The Future' is trying to do the same thing, which is saying there are affected areas that need to be delved into in terms of African cosmologies. We are here to probe those ways of seeing.”

Read this next: A deeper African source: How grime and afrobeat is influencing UK jazz

I become fascinated by how his fellow bandmates join him in this seemingly complex headspace that is personal to Shabaka and has required much depth of thought. He outlines the importance of balance within the ‘collective’ in allowing this to occur, mentioning that they would do breathing exercises before recording each track and not eat meat for that entire period. This catered for a shared relaxedness that became key for the creation of the music, as Shabaka describes his approach to nurturing this feeling as a band leader. “Everyone has to be as free to express themselves as possible without thinking that they are making a mistake or can’t do something. If you can create a scenario where the musician can be free and know that they can express themselves fully as individuals, but in the service of the collective, then that will become the worldview coming out.”

The feeling of becoming lost in the music is something that anybody who has witnessed a Sons of Kemet gig will be aware of. The stamina that the band embody to keep playing explosively without stopping is a key part of their performance. For Shabaka, it is a conscious trope that is crucial for the experience of the listener, probing them to lose a sense of time and physical space, and rather enter a more spiritual, sonic space.

“It’s about getting into a place of trance and staying there. What I find happens if you stop, or introduce tracks, or have banter with the audience, it takes you out of the theatre; out of the role that you are entering; the spiritual headspace. You inadvertently start objectifying your own performance because the performance becomes something detached from you. Whereas if you are just constantly doing the performance, there is no detachment. It’s about staying on the line. Anything that takes us away from that connection is what stops us from being in that trance space and achieving that higher level of where music can take us.”

However, the trance space that was afforded through the intimacy of live shows was something that was of course paused in March 2020, as the pandemic hit. I become intrigued by the switch in pace this brought to Shabaka’s life and how it informed his creative process, which has been historically underpinned by constantly performing. In 2019, he performed a mind-blowing 145 shows across the world with his three collectives, but 2020 demanded a huge adjustment in terms of lifestyle. I inquire as to how he dealt with his rigorous touring schedule in 2019 as well as how he was able to adapt to the shift that followed.

“In 2019, I had just about reached a stride in terms of understanding what and when to eat when on the road.” He speaks about how he would observe a consciously healthy diet that would complement the intense demands of touring. “It sounds easy but it’s actually quite easy not to do. In 2019 I was more or less vegan, I didn’t eat any straight up dairy. And if the meat isn’t there to break down in your body, then you’ve got more energy.

“Once you realise what it is to be fully energised, then you start to know what actual things you put in your body that take away from that full energisation. I found the cleaner and more natural I am, the more energy I’ve got and the more I can actually give a good performance night after night.

Read this next: The year of no gigs

“It’s the same when it comes to breathing exercises, doing lots of those with the group. The same happens with when I’d eat. I would eat four hours before we would play, so the food is digested by the time I am on stage. Doing exercise every day.

“Then, when it came to 2020, in terms of the shock of not doing those gigs, it was just up and down. A lot of people had more similar experiences than one would appreciate. It was discombobulating. A very strange time. You couldn’t just keep practicing or keep doing what you’re doing because you didn’t know if anything else would be happening again.”

I ask him about the incentive to create that album, knowing the touring wouldn’t be happening anytime soon. He tells me it was even more important to create. “Knowing we weren’t going to be performing, it meant we definitely needed to have the album, because maybe recorded music would have been the only thing that does continue.”

“It was just a struggle to find meaning and find things that felt meaningful. And those things that felt meaningful shifted and changed throughout the course of the lockdown. That was the process. Trying to figure out what I needed to do that would make me feel inspired and energised. There were many times when I didn’t know and was going to stop doing stuff.

“Fortunately, I’ve always found what I needed to do. That might be not practicing the saxophone or clarinet, just practicing my flutes. Or it might be not practicing at all and just reading. Or it may be playing chess. Or just listening to music.

Read this next: Eerf Evil is leading a UK jazz-rap revolution

“It was many different things. I just realised that there is a difference between resting and rejuvenating. I found that what was needed after all of those years of touring wasn’t for me to rest, it was for me to rejuvenate. The difference is that you can rest without rejuvenating. You can stop.

“A lot of people say that ‘you can’t be too hard on yourself; you’ve got to give yourself a chance to break and not do anything.’ But I found that as soon as I stopped doing stuff during lockdown, I started to think about the severity of the situation, my mind started to go into some very strange places.

“It was considering things with impotence. It was considering things that I wasn’t in a position to change and not with any solutions. I realised that in terms of rejuvenation – if I just rest and not do anything - it’s not giving me any energy or spark to create or produce anything. The only thing that does that is just for me to do things that I’m invested and interested in. But I have to search out to figure out what they are because they may be different to what they were in 2019.”

For Shabaka, one of the most meaningful forms of fulfilment he found came via the medium of social media; something he is equally cautious of, following no accounts on Instagram in order to ensure he doesn’t waste his time. However, he saw the platform as a feasible way of communicating with his audience that he was now so detached from, as that connection shifted from the physical space to the digital space.

“I found a lot of meaning from just making Instagram videos and being diligent about that. Some musicians spoke about their hesitance to give too much online because it’s devaluing the giving of music in a commercial structure but there’s an element of my engagement with my audience that’s beyond the capitalist structure. That is actually about me sharing with an audience and feeling the reciprocity in terms of what they get from it, so I found that me deciding that I am going to do an Instagram video every day or two, finding interesting things that I am going to do with them.

“Getting the response from the audiences when you put something up online gives you some meaning. Especially in those days where it felt like we’d perhaps never perform again.”

Read this next: London's Steam Down is at the forefront of the UK's new jazz age

He appreciates the multi-dimensional aspect to social media, but affirms why it is something he is wary of too. “I want to go to things on the platform as opposed to getting things put onto me, so that’s why I still use it. I started to realise a long time ago that mental space is valuable. We are competing for space. Not necessarily space itself but attention. What you decide to focus on. There are infinite things that you can be focused on. I didn’t want the focus of my attention to be dictated by these platforms solely. It has the tendency to make things seem urgent in a way that is unnatural. We don’t need to know about what’s happening today, yet we are made to feel like we do.”

He takes a great pride in the nature of his audience, characterising them as “trusting”, allowing him to take risks and be met with feedback. He ensures, however, that he creates what he feels without trying to focus on pleasing them. For him the creation of music comes from a deeper feeling. “If you consider it is not you who is making the music. You're creating within your musical career, body or mind. You are creating a situation in which you can be a conduit for music to coalesce.”

The transferal of energy into sound is the most crucial equation for Shabaka, referring to anything outside of that as “just a distraction.” Yet a large part of understanding that feeling comes from connecting to both the ‘natural’ and ‘spiritual’ spaces. Waking up early every morning of the last year and going to his local park to play his flutes amongst the trees has allowed him to deepen his craft.

“It’s deep on a number of levels. One is, I have gotten into playing really quietly. I do it a lot in the house now too. It works all the same muscles and techniques. There is something else to be said about playing quietly whilst projecting the sound. So, I don’t go into nature and just blast the sound. That’s another example of man just going into nature and trampling over the natural space and dominating the sonic space. There’s a way of playing quietly but allowing that quietness to merge with the natural sound. It’s something you can only get when playing in nature. You can only understand that level of projection and the coming together if you play outside.”

The natural setting has been vital for allowing Shabaka to reach the spiritual depth that forms when he plays his instruments. For him, it is that very spirituality that is the fundamental basis to being an artist and creating work. “It’s about connecting yourself to that form of energy that can then allow you to be creative. You might call energy spirit. For me, it’s about connecting to those and seeing that as the peak of what it is to be an artist. For me, to be an artist is to be spiritual. Whether you believe in a specific doctrine or not, it’s about understanding that you are a conduit for life-force. And that you reflect that life force with sound. And that sound can have any genre or vocabulary that you can be culturally influenced by. There are no boundaries.”

The new Sons Of Kemet album ‘Black To The Future’ is out now on Impulse! Records

Haseeb Iqbal is the author of Noting Voices, follow him on Instagram