Features

Features

Rave photographer Matt Smith: “It’s about documenting what people bring to the party”

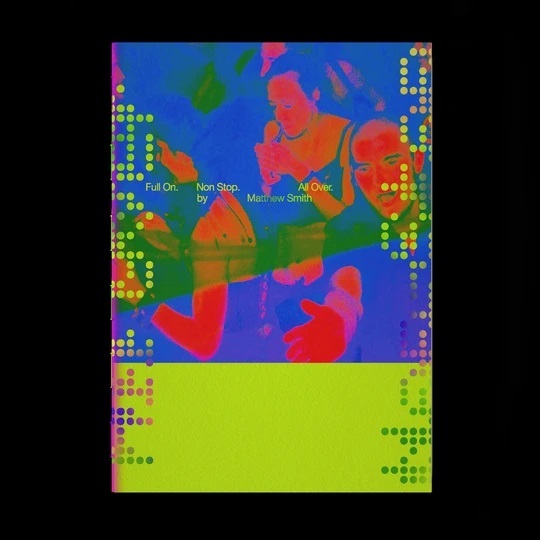

Tope Olufemi speaks to Mattko, whose new photobook Full On, Non Stop, All Over documents early 00s rave culture

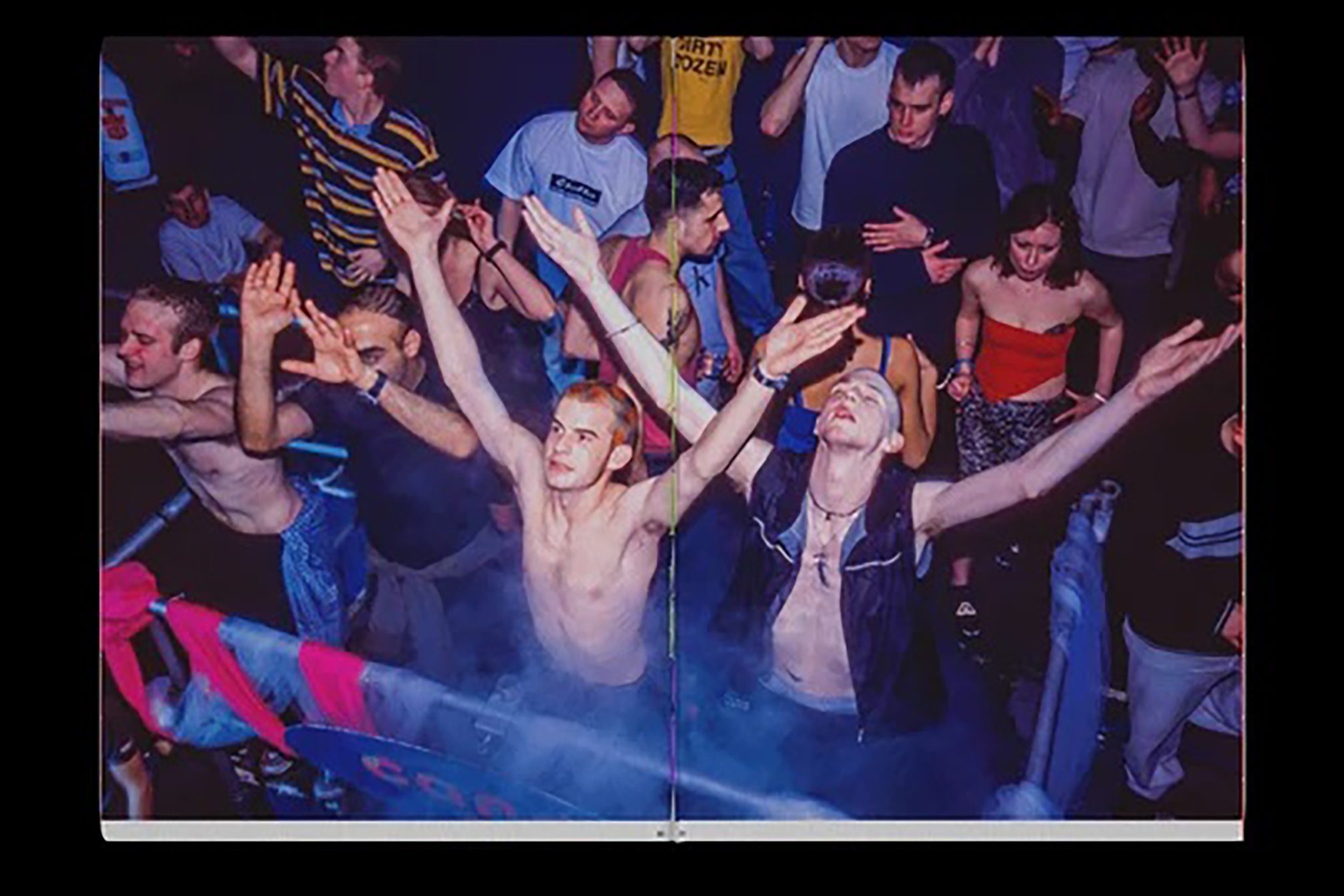

Matthew Smith, AKA mattko, has been attending raves since the late 80s, but his career photographing them didn’t begin until rave was criminalised by the Criminal Justice Act in 1994. “It was a direct response to our freedom being criminalised and restricted that motivated me, and it still is now” Smith told us.

Full On, Non Stop, All Over is Smith’s new photobook documenting rave culture between 2000-2005. It follows his 2017 photobook, Exist To Resist, which looked at the politics of resistance within rave culture in the 90s. The criminalisation of rave has played an important part in Smith’s work, which often attempts to understand the discontent amongst rave communities and the ways rave is maintained in spite of this criminalisation.

Read this next: A new photobook documenting 2000s rave culture is coming out

“Making your own entertainment is now an entry level crime allowing people's lives to be invaded by the state for profit, data mining and surveillance,” Smith asserts, and his work sets out to archive rave and the ways it brings communities together regardless.

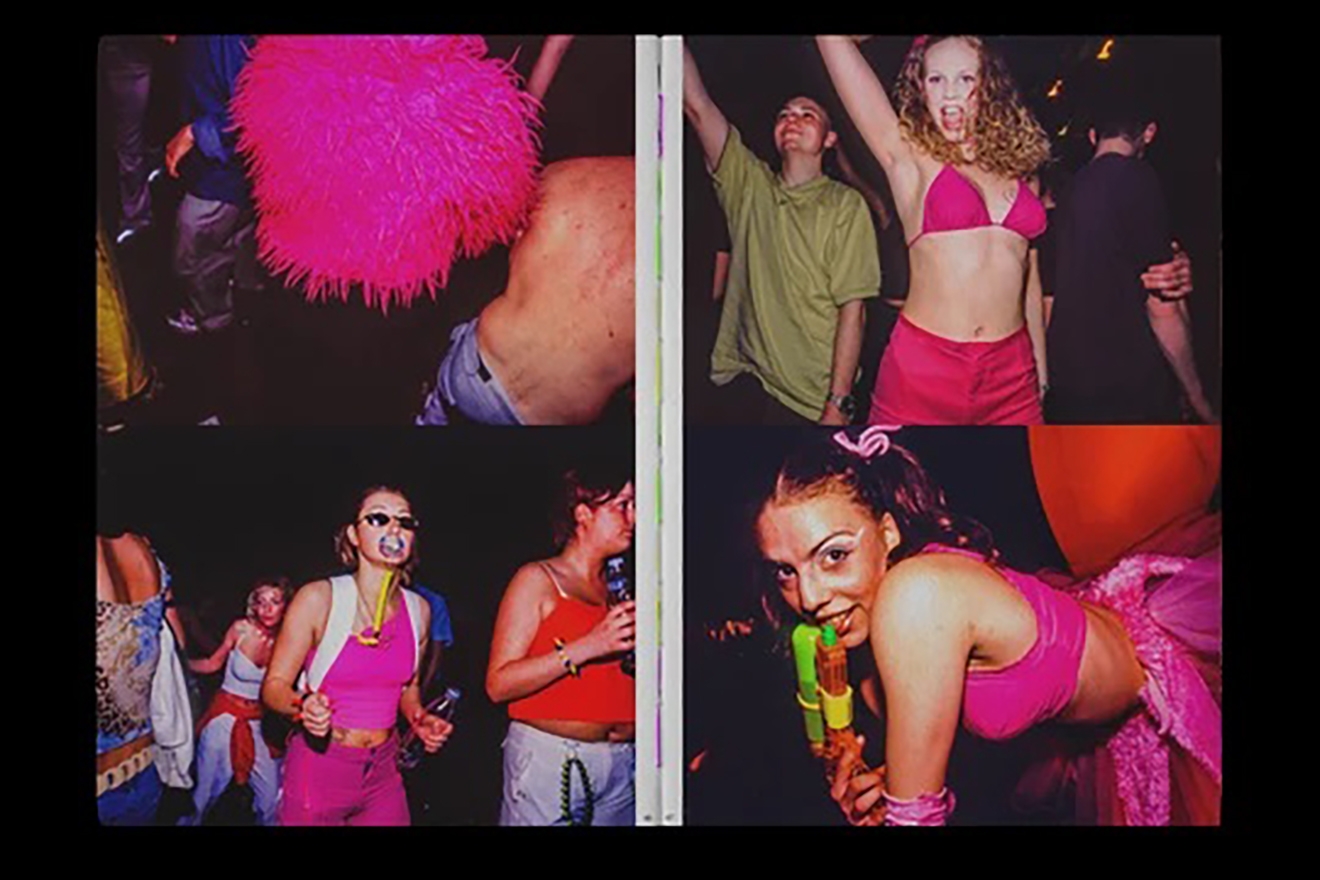

Smith felt that now was the time for a book like this, as a way to both look back into the past and look forward into what could be for the rave as nightlife plans towards re-opening. The photographer recognises the importance of the archive, and how this can be hopeful at such a dismal time, with nightlife suffering under the pressures of the pandemic - and public morale at an all time low.

“I wanted to shine a light in that darkness and remind people of a time when the unfettered joy of raving was everywhere and provide a little visual antidote to the misery. To show that what once was could be again.”

Read this next: Roaring 20s: Why club culture could surge this decade

3000 rave images were boiled down to 300 across 192 pages by Smith and Trip Publishing, capturing the energy of the rave that has been so sorely missed over the past year, and features a foreword from Simon Reynolds, author of Energy Flash.

“It was thrilling when Trip told me he wanted to get involved. His words have a lyrical eloquence and poignancy that brings something unique to the work and when you are an artist its part of the job to make what you do as interesting as possible to your audience,” Smith said about the foreword.

As we get back to the hustle and bustle of nightlife, with gradual re-opening and easing of lockdown restrictions, we caught up with Matthew Smith to talk about Full On, Non Stop, All Over, the future of the rave, and its part in bringing us all together.

Full On, Non Stop, All Over explores rave culture between 2000-2005, why that period specifically?

The people, the music, the behaviour, the celebration and the style were all still there and incredible, but because entry fees and bar prices were paid raving wasn't illegal anymore. The ironic nature of that idea is something I really enjoy and it has a distinctly contemporary relevance. It's a very capitalist phenomena that it's ok to engage in criminal behaviour as long as you pay to do it. Hypocrisy and government have long gone hand in hand.

The first few years of a new Millennium are historically a very important time. 9/11 provided the excuse to launch Project Fear and that is a process which hasn't stopped since. Crucially those years are pre-smart phone so people are still really in the moment and loving raving to the max.

What inspired the name Full On, Non Stop, All Over?

Its multi-layered. The phrase is traveller raver hype language. It's from a flyer for some massive squat parties we did in London with a rig called UNSound. I've got an image of the front of my mates massive circus truck with it painted on the spare tyre mounted on the front of the cab. It also describes perfectly the spirit of the times in which the images were made. Just like your question there were moments when I considered having a question mark at the end but in the end I thought it was better to let people make up their own minds.

Read this next: 20 iconic illegal rave photos

How did you go about capturing the energy and spontaneity of the rave?

You must have energy and spontaneity of your own. It's always about what people bring to the party. The images are both interactions and interventions made with empathy and affection. There's a very performative element in making this kind of work that has to be both subtle and natural if you are going to engage people in the heat of the moment. For me raving has always been about inclusion and diversity. The collective nature of the experience is what makes rave such a powerful and positive social phenomena.

How important do you feel archiving is for preserving rave culture?

Very! My work is rooted in folk history, camp fire tales, personal experience shared, political conviction, the telling of history by someone other than the victor. It's an important thing to do and a great way of making art that is socially relevant with added benefits for future generations. The bottom line is showing people how simple freedoms are being eroded and asking them to do something about it.

How do you feel the pandemic will change the rave in future?

It already has in a big way. Festivals have been stopped, nightclubs shut down. The damage to promoters, performers, musicians, and all of the supply industries that enable events have suffered massively. Skilled staff have had to find other more reliable employment. Confidence in the industry as a means of earning a living is at an all time low. The insurance companies that have made huge profits from underwriting the creation of culture in the past have run a mile from insuring the risk assessments of that same cultures future. Meanwhile everyone's mental health is suffering from enforced isolation.

On the other hand on the spot 10 grand fines have been issued to free party organisers to ensure future financial slavery for anyone daring to produce culture without a license. Huge and publicly expensive police operations have used brutality to attack ravers. Police dogs have been set on young girls causing life changing injuries. Who knows what the future will hold but the current indications are not good.

You’re featuring in the Vanguard exhibition at Mshed in Bristol, how instrumental was the city in the development of rave culture?

The show in Bristol is all about the evolution of Bristol street art. They asked me to acknowledge how our free party and protest work in 90s Bristol helped to unite the community and define the aesthetic that inspired the art. The fusion of the free party spirit with city's multicultural musical background of hip hop, reggae, rap, and drum 'n' bass provided a potent catalyst in both the creation of art and rave culture.

The art adopted the iconography of rave and the attitude of DIY culture. The casual anarchy of the city back then played its own unique part in giving street art a voice, and rave culture one of its spiritual homes. It's great to be showing work on the same walls as the Bristol Massive and its going to be well worth a visit. If I'd been using a spray can and stencils for 30 years I reckon I would be pretty good at it, but instead I made free party protest and used a camera that made negatives. Negatives are essentially very sophisticated stencils that use light instead of paint to create images that tag my presence through place and time. Quid Pro Quo innit.

What are your plans for the future?

When Trip first approached me about publishing the work in the book it became obvious that there were alternative outcomes to think about in addition to the print. Photography is all about what it can be as a medium, and increasingly that means it is up to you as an artist to devise new ways of creating art from it. For me this means going back to my roots making raves and creating environments.

In the early stages of the production it seemed sensible to explore the idea of re-populating a darkened, closed club space with the images from the book on screen or via projection with music triggered by socially distanced human presence in the space. The Printworks vast hall immediately came to mind as a venue, then I started to think of the Turbine Hall at the Tate. Imagine what you could do with some state of the art production in a space like that.

Apart from that Exist To Resist needs re-publishing. The story of the original Kill The BIll protests and how they came to have that name needs taking to a wider audience in the light of the recent re-invention of that slogan during the unrest in Bristol and elsewhere. There’s an incredible Glastonbury book just waiting to be made from my archive. There is also a book about Bristol street art in its early days from work that dates from the same time as Full On Non Stop All Over. Then there's a major retrospective to think about. Whatever happens the future will be all go...

You can pre-order Full On, Non Stop, All Over here

Tope Olufemi is Mixmag's Digital Intern, follow them on Twitter here