Features

Features

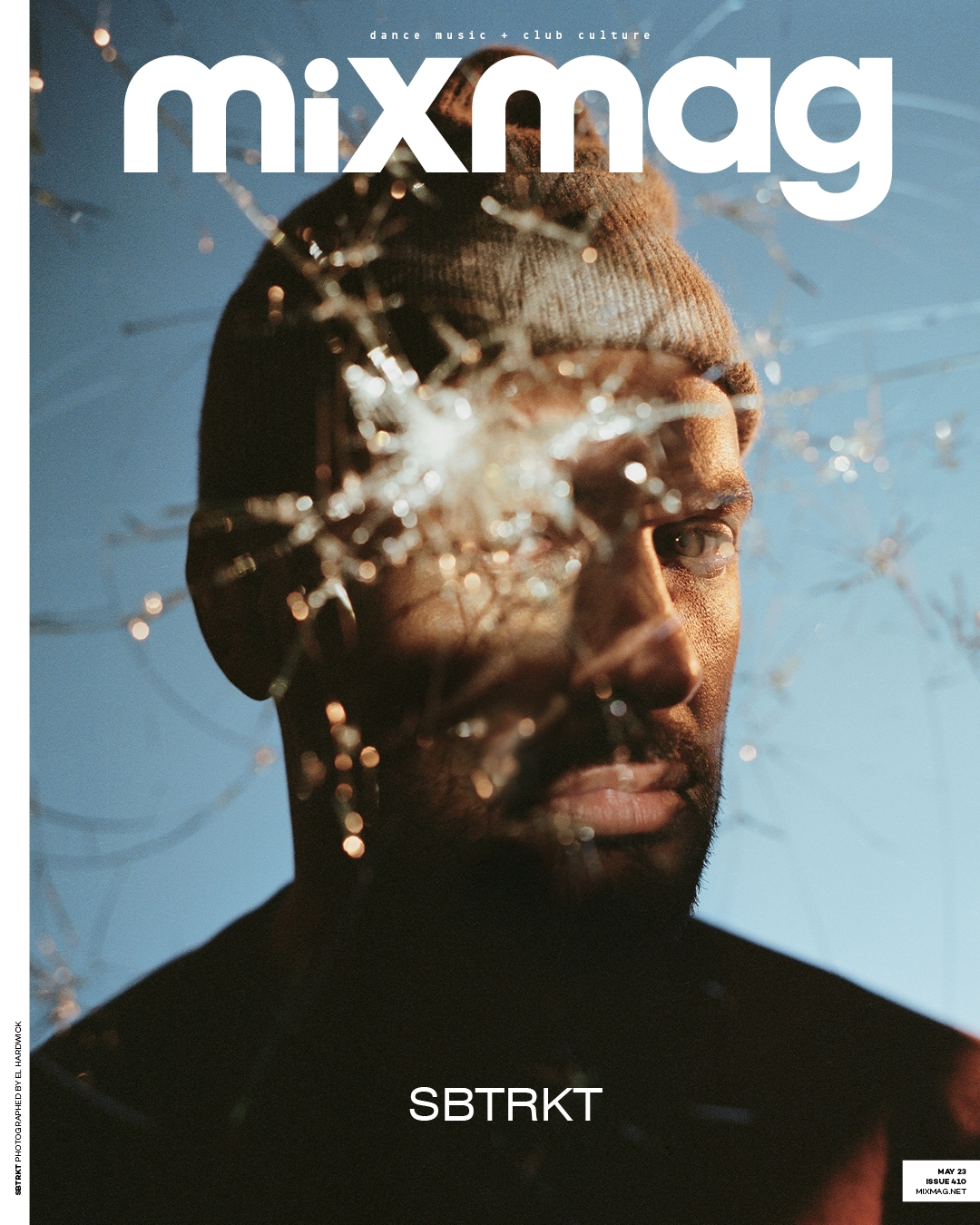

SBTRKT is ready to tell his story

In a mask off interview, Aaron Jerome AKA SBTRKT speaks to Dhruva Balram about his new album 'The Rat Road', industry frustrations, and why he's - still - letting the music speak for itself

A slight mist from an aroma diffuser twirls its way through the dimly lit studio where synths are stacked neatly in stands nearly touching the ceiling. Pedals are tucked into a corner, drum pads and mics occupy another. An array of various instruments are packed in cases behind the drum set. There is a fond affection in Aaron Jerome’s voice as he recounts using the equipment on his past tours as the influential artist SBTRKT. The North London studio feels like a microcosm of his world: a cinematic setting which we’ve now spent hours within. After nearly six months of Zoom calls and in-studio conversations, today is the final time we’re speaking before ‘The Rat Road’, his first album in six years, is released.

Jerome is erudite and speaks with clarity. He flits between sarcastic quips, cynicism and earnest hopefulness while pondering philosophically on the future of the music industry. 20 years of experience tumbles out: at times, he’s racing to catch his thoughts. Initially, at the tail-end of last year, there was a certain caginess, but as the months passed, he let the veil fall. Notorious for spending the initial years of his fame and success enveloped in a cloak of anonymity - most famously a version of a tribal mask during performances - Jerome recognised that he was entering a new era. Now, he wants to tell his story.

And it starts with ‘The Rat Road’.

“There was a time where I felt like I’d overcooked [the upcoming album],” he says while playing with his shoelaces. “I probably spent too much time, like a year or so, working on a single song as I was on my own time. But now, with the record I created, I’m very proud of it, fulfilling what I wanted to make.”

‘The Rat Road’ demands multiple listens as the subtler elements of the production - like the metal nails in American artist Teezo Touchdown’s hair clinking on ‘Waiting’ - are neatly tucked away. With its orchestral strings and cinematic keys, opener ‘Remnant’ sets the tone for the entire album, which synths play a major part in. It introduces the listener to arguably SBTRKT’s strongest project yet: a dense and lush 22 tracks of precision where intention is found throughout. ‘The Rat Road’ is methodical with coiled energy; SBTRKT never unleashes it, keeping it at bay, allowing it to simmer.

Following a nearly seven-year break for the musician, the album’s release simultaneously signifies the beginning and end of eras, one of which started with his self-titled debut album in 2011. With its ability to playfully skip between genres, sometimes within the same track, it was a generational project which went on to influence scores of artists, including British musician SHERELLE, who called it “a formational album”. The release of ‘SBTRKT’ led to a subsequent whirlwind five years. Alongside two further releases in 2014’s ‘Wonder Where We Land’ and his first independent release in 2016’s ‘Save Yourself’, there were remixes and collaborations with record industry heavyweights, as well as multiple world tours, festival headline shows and the death of his brother. All of this left him feeling jaded and tired.

“The music industry is so in flux with the way you could create income,” he says, leaning forward in his chair. “You haemorrhage money but you don’t see that return unless you start doing some crazy corporate stuff, but I just don’t have the skills to be open enough [to say], ‘here’s my image, do what you want with it.’ When I was wearing a mask, that could easily be taken by anyone and turned into a gimmick. It made me feel really fragile about the fact that I spent so much time on music, but my identity was being exploited in a different way.”

Read this next: The Cover Mix: SBTRKT

SBTRKT retreated from the public eye while Jerome stepped in to observe the landscape. He found that he wasn’t connecting with anyone in the UK and increasingly spent more time in Los Angeles. Working with artists like Steve Lacy, nothing came to fruition which he wished to release immediately. So, he went inwards. Jerome asked himself questions about the industry, his production and what his fans wanted versus what he wished to deliver.

“The core of that is working out what people perceive SBTRKT to be [currently] and how it will be perceived in the future,” he says. “So, I had to work to create something that I’m proud of, to introduce the next era, to not be stuck in the past.” He went to the studio and refined his skills, levelling up his production and understanding how he could build on what talent he already possessed. Self-taught throughout his life, Jerome spent this time understanding how to take what was in his head and bring it to an audience. He estimates that during these years, he made “more than 2,000 songs.”

As the COVID-19 pandemic became endemic, the first sketches of an album release were formulated. An opportune moment in September allowed SBTRKT to mark a significant return. At Dialled In, a festival showcasing British South Asian musicians [full disclosure: this writer is one of the co-founders], which took place in Walthamstow, London, he played a spontaneous secret set. Spurred on by his friend and fellow attendant Skrillex, SBTRKT played publicly without his mask for the very first time. In one fell swoop, he had not only revealed his ethnicity and face but made a statement. “If there was ever a time and space that felt comfortable to not have to hide your persona, that was it,” he says.

Since his appearance at Dialled In, he found that the industry wanted to almost instantly place him into a South Asian box. Offers came in from corporations and DSPs who had a bonafide star earmarked to be the face of this new underground. SBTRKT turned them all down. “With hindsight, having seen the landscape of things, it seems kind of obvious to me as more people found out,” he says. “But, I wasn’t fitting myself into enough of a box [for them]. I’m not fitting their character that they need me to be, like putting in a tabla in my songs.”

“I knew I didn't want to fall into that category,” he continues to say, “but since Dialled In, I created so many connections. Honestly, they were more supportive in different spaces than what I’ve seen from other people in the industry [especially] as I grew up in a place in the ‘80s full of racism.”

Born in rural England, Aaron Jerome is the son and grandson of farmers. With a family ancestry that traces itself through East Africa and India, specifically Goa, as well as Scotland and England, Jerome grew up thinking he would work forever on a farm. “My holidays were essentially walking up and down a field,” he says with a laugh. “Sitting on a tractor or a combine harvester, picking potatoes, that’s backbreaking work. My mum was never keen for me and my brother to do that, but, obviously, I didn’t know that at the time.”

Every other weekend, Jerome would spend time with his mum’s family in London where he was introduced to the world of DJing and vinyl culture through his cousin. “His room was full of vinyl,” he says. “I would just go and sit there and be transmitted into this whole space that I didn’t know existed. It was such an alien culture: the attention they had to the vinyl itself, the way they would hold it and flick it around.” At age 11, Jerome was obsessed. He patiently worked out how to DJ using a cassette tape and vinyl — the first iterations of a lifetime of self-teaching. Then, he started using a MIDI keyboard to begin making music and his love for hardware bloomed. He was hooked and never looked back.

Read this next: How Asian Dub Foundation's stand against racism connected generations of British Asians

During the week, however, Jerome attended a white-majority school “a million miles” away from the South Asian-focused gathering with his cousins. He was “considered a bit of a weird person because I was into records and club culture”. “In my first year of school, I got off the bus and two kids started shouting the P word at me,” he says. “They were dragging my knuckles right across the wall. I was five years old.”

Jerome entered his formative teenage years and early adulthood in the late ‘90s when the South Asian Underground teemed with influential artists such as Talvin Singh, DJ Ritu and Nitin Sawhney. As a mixed-race child who grew up primarily in rural England, Jerome didn’t necessarily see himself reflected in it, but found that the music which derived from the scene enlightened him. “They were challenging electronic music spaces in different ways,” he says. “I was attracted to that side of it. It was definitely an influence, but not necessarily because of people’s skin colour — it was musically. To me, [Nitin Sawhney] was the same as Massive Attack, Masters At Work or Daft Punk. This similar broadness of not having a box.”

Moving to London at 18, Jerome started remixing. ‘The River’ by Nitin Sawhney ended up as one of his first-ever remixes, followed by releases across Good Looking Records and BBE before the world was introduced to SBTRKT. Numbers, Grizzly, Ramp and Young were some of the initial labels SBTRKT released on while he continually attempted to “break down doors to the music industry” which were previously fiercely guarded. Of those early releases, some, like Jessie Ware collaboration ‘Nervous’, were aired regularly on Boiler Room while others became anthems throughout London club night culture. Tunes like ‘Living Like I Do’, released before SBTRKT’s seminal 2011 self-titled album, still find themselves being spun to this day.

Read this next: “We exist in more than one narrative”: Sarathy Korwar & Idris Rahman in conversation

His live shows were an “ever-evolving experiment”, where he added “new gear continuously while, at times, free-styling with track structures and form”. These shows became essential viewing on the festival circuit. “I was challenging myself to go way beyond my comfort zone,” he says. “I wanted to build a show on par with artists I had grown up watching like Massive Attack, albeit without the budgets.”

Now, as he gears up for his first live show in seven years at the end of May, the 42-year-old wonders aloud how the audience will react. “When you’re promoting an album or a body of work with different strands to it, the question asked is, ‘Where are you going with it?’,” he says. “Are you being presented by your original first music? Or are you being presented by what you actually create now? A lot of my first releases were in a [certain] era. So, are you being pigeonholed by solely that? Or are they listening to the actual [new] song? And actually judging it based on that?”

These questions extend to Jerome’s frustrations with the industry’s reliance on Digital Service Provider (DSP) culture, a recurring theme throughout our conversations. “The systems of gatekeeping have changed, the gatekeeping hasn’t,” he quips.

Unfortunately, SBTRKT is working in an era of singles and genre-specific playlists dictating chart placements and streaming numbers. “I'm not interested in doing a lot of opportunistic things,” he says. “I've only put music out on my own terms. I want to only perform within spaces I’m comfortable in. I don't write records to fit a certain shape and box to work.

“I’ll create something that responds to my emotional place at that time and [that] will grow with collaborations. We’ll take it to a whole other level in emotion with wherever that person’s thoughts and processes are.”

An over-reliance on DSPs has shifted the balance of power away from artists and musicians. No longer does the actual music matter, but often, it’s about “who you know” at DSPs. This extends to social media as well. Jerome mentions Amon Tobin’s recent tweets where he states, ”we can't let fire emojis be the measure of our worth and absolutely have to build our own communities,” which encompasses how he feels about an overreliance on an ever-changing algorithm.

“Because of streaming culture,” he says, “There’s no languages, there’s no commentary as a way of being able to decipher things. Everything is broken down into singular songs and driven through a stats-based culture.”

In an era wholly dependent on these numbers and stat padding through collaborations, Jerome is not of the belief he could have come up in this day and age. “Because I think you have to have a very singular USP,” he says. “Or you have to have one track and that’s a moment that stands out and then you’re tagged by that or whatever else you should put out next. There’s not really the space for growth. I'd already put in 10 years of work before I got my first album. I made my mistakes and practiced and got to the point where what I created, I felt worked.”

Certainly, anonymity is not possible, especially in an era of social media dominance where algorithm changes at the whim of a corporation dictate the visibility of an artist. The mask had become associated with SBTRKT, but Jerome had spent the last few years contemplating appearing without a mask for his album. He didn’t want it to seem “contrived” and although there wasn’t a specific decision to do away with the mask at Dialled In, Jerome quips: “You can't exist on social media without a face anymore.”

“That's partly true,” he continues to say, “but it's not my reason to do it. Because I can't stand looking at my face. I don't want to see it everywhere. I had been thinking about [playing without a mask] before I was even getting into album campaign mode when I was going to appear without a mask.”

“I would say it would be hard to start out now without feeling like it was a gimmick,” he says. “Obviously, we’ve seen it so many times through different artists and different methods. I think anonymity [now] feels very much at odds with the culture.”

Scattered throughout ‘The Rat Road’ are references to this vexation, to SBTRKT’s internal dialogue during the intervening years of the album. The title ‘You Broke My Heart But Imma Fix It’ references both his annoyance with the industry as well as wider societal issues with the burgeoning cost of living crisis. “I’m feeling like everyone feels a little bit entangled in a web of not being able to control what’s going on around,” he says. “It’s a personal industry thing, but it’s also very much about the world we’re in right now where you can’t have ultimate control over things even as an independent artist.”

Read this next: Riz Ahmed: “Home is a place that we're creating through our art”

With its expansive broad sound, ‘The Rat Road’ certainly doesn’t fit into any genre-specific box. Its long list of collaborators reads as such with D Double E, Teezo Touchdown, George Riley, Sampha, Leilah, Anna of The North, Kai Isaiah Jamal, Little Dragon and Toro Y Moi all appearing. In keeping with the SBTRKT world, it’s a vast all-encompassing list which touches upon genres and sounds that meld with the British producer's vision. It doesn’t feel label-led or stat-driven; rather, there is a genuine connection here.

Toro Y Moi and SBTRKT first met in 2012 in Australia. Six years later, they started making music together and over several sessions spanning multiple countries, the duo were able to work together on ‘Days Go By’ as well as ‘Demons’, two tracks that sound wholly different from one another. The former is a euphoric, almost anthemic sun-soaked tune while ‘Demon’s plays like a lullaby, twirling itself around polyrhythms, apt for being blasted through the speakers, arms wrapped around a lover or listening to it intimately with headphones on.

D Double E’s appearance stemmed from a conversation SBTRKT had with his wife. What followed was a similar path to the Toro collaboration where the duo worked on multiple versions before landing on ‘D Double E (Interlude)’ with the stand-out couplet, “got to protect my energy / got no love for the enemy / people think there’s 10 of me” which Jerome felt reflected SBTRKT aptly. “I thought that was a sick line,” he says. “As in the past, no one knew who I was. They thought I was more than one person.”

Throughout the album, it feels like SBTRKT is driving a car through London, windows rolled down. Rather than discussing what’s on his mind, he’s put the aux cable in and plays ‘The Rat Road’ so that he can let people into his world and his thinking. “I want people to listen to my record for a while and understand it in the sequence order,” he says. “I think as a whole they do feel more cohesive and you’ll understand more about SBTRKT clearly and not be fixated by singular collaborators or singular songs or styles.”

With an album in the world, a live tour spanning London, and New York City and a festival appearance at Field Day, SBTRKT is well and truly back. He hopes that he can come away from this “releasing more frequently” as he wants to show that “as an artist, you can be able to freely create music without boundaries or constraint and not be sat in a space where people only respect you for something you’ve done historically. I definitely feel like we’re in a climate where, especially as an artist who’s had that past success, I’m still battling,” he says.

With his methodical, calculated approach to releases spanning the production, sequencing, artwork and release campaign, SBTRKT’s next release may be like the promise of the horizon which one anticipates from a ship but never reaches. What matters is that right now, we have ‘The Rat Road’.

“Let's not forget front and centre of this is, music should be the most powerful tool to paint a picture and explain your point of view,” he says. “It has always been a way of narrative building. The answer [moving forward] basically doesn’t involve Instagram posts.”

‘The Rat Road’ is out now, get it here

Dhruva Balram is a freelance writer and critic, follow him on Twitter