Cover stars

Cover stars

Kerri Chandler: A timeless house music icon

King Kerri's as relevant today as he ever was

The year is 1978, and a young Kerri Camar Chandler has, as usual, patiently waited for his father Joe to take off and do his hustle on the streets of East Orange, New Jersey. The front door closes; from behind the drapes Kerri furtively peeks out of the window as Joe swings a skinny leg over his 10-speed bike and takes off down Steuben Street. It’s a hot, muggy summer day in the Kuzuri Kijiji projects, but Kerri’s cool as a cucumber. His 13-year-old belly fills with butterflies: it’s game time.

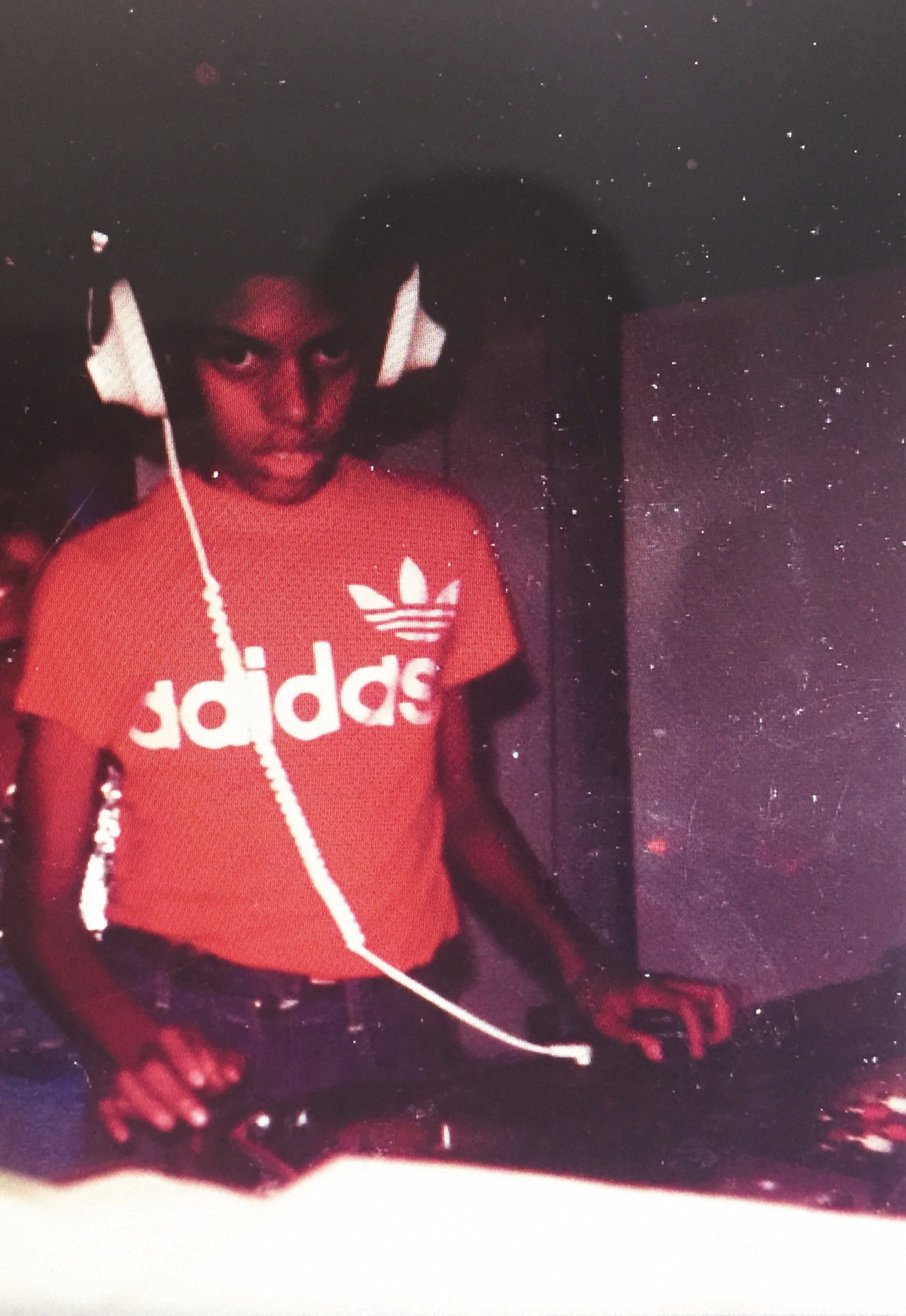

He sprints to the living room, so excited he misses a step and faceplants against the shag carpet. Not even pausing to swear, Kerri pops up, grabs a dining chair, and drags it over to the Thing That Shall Not Be Touched. There, against the wall, seemingly glowing like the Holy Grail, sits his dad’s DJ set-up: two modified Acoustic Research XA turntables, a Clubman 101 Meteor mixer, and enough vinyl to make Carl Cox double-take. A smile steals across Kerri’s face. He wipes sweaty hands on his red Adidas T-shirt, pulls a weathered copy of Lonnie Liston Smith’s ‘Expansions’ from the stack, and drops the needle. Fireworks go off in his developing mind.

For the next couple of hours Kerri performs the routine he has for months: perfecting his budding DJ skills while keeping a well-tuned ear to the front yard, perpetually listening for the rhythmic chain of his father’s 10-speed approaching. But on this particularly muggy, hot day, Joe gets a flat tyre and walks his bike home, already furious. When he opens the front door he see his son Kerri, white Panasonic headphones wrapped around his head, holding a 12” maxidisc of Jakki’s “Sun… Sun… Sun…” in one hand and the turntable platter in the other. There’s music blasting out of the speakers. The look on his son’s face is one of pure, undiluted terror.

“It was the bassline. I was like, ‘I gotta hear this damn bassline!’” recalls Kerri Chandler, the details of decades ago as fresh to him as if it was yesterday. “That’s what he caught me on. It seems comical: I’m standing on this chair like a little kid, record in hand, and in he walks. Busted!”

Surprisingly, what Kerri sees on his father’s face isn’t the explosive, volcanic anger he feared, but rather a look of weaponised exasperation. “What the hell are you doing, Camar?” he fumes. Despite his rage he cuts a slightly ridiculous figure in the doorway, sweating profusely in short shorts and green and white Adidas. “That costs a shitload of money, son – I gotta work with that!”

Kerri just stands there, paralysed. “Well, I’m DJing.”

“You don’t know what you’re doing. Get down from there, you’re not a DJ!”

“Well, yeah, I am a DJ,” replies Kerri, slowly regaining his confidence. “I’ve been watching you for months.”

“I’ll tell you what, DJ: show me what you can do.” Galvanising his anger, Joe lays down a test for his trembling son. “If you can DJ, I’ll bring you to the club this weekend. You can warm up for me.” He pauses, real slow, twisting the end of his statement like a blade in Kerri’s gut: “But if you can’t, I’ll crucify you.”

The ultimatum: fucking spin, son, and show you got skills. Or face the consequences. Panic washes over Kerri like a cold shower. “All I could see was myself, like, in a Jesus Christ pose,” laughs Kerri now.

The young boy slips a Martin Circus vinyl from the pile, cues up the record, and proceeds to blow his dad’s mind right back onto Steuben Street.

“I had a few records that I had routines with, just to mess around, so I started mixing these disco records together. And he looks like he wants to cry. He’s just looking at me, like, ‘Wow, you know where all the breaks are, you know where all the parts are! You’re working double records!’” Kerri recalls.

Little Kerri drops Kano’s classic ‘I’m Ready’, Sharon Redd’s ‘Can You Handle That’ and Donald Byrd’s ‘Places Snd Spaces’. It’s an all-out disco and funk assault. When he can finally speak, Joe says “Son, I’m taking you to the Rally Racquet Club this weekend.” A look of unmistakable pride washes over his features. “You’re gonna start opening for me.”

"I remember the reaction I got: I'd never seen people dance like that"

And that was the day Kerri graduated from undercover DJ to real-world DJ – or as they called him in his dad’s club, ‘DJ Little Man’. Permanently taking over the 9–10:30pm time-slot, he would stand on a crate every Saturday night, in an ironed suit and tie, throwing down records while the citizens of New Jersey went buck-wild to the music emanating from the speakers.

“I remember putting ‘Disco Circus’ on,” Kerri says of the first record he played at his dad’s club. “I’d always wanted to run the break – I kept running it over and over. I remember the reaction I got: I’d never seen people dance like that, like that kind of aggressive, happy reaction. I was like, ‘I’m not letting this go. I can make people happy, and I’m controlling adults with records?!’ It was just really strange to me; I didn’t know I could get away with something like that.”

There, on that wobbly crate, a legend was born – even if no one recognised it at the time.

Forty years later, on the other side of North America, it’s a chilly late January evening in Seattle, Washington. The time on the glowing clock of the W Hotel suite reads 4:16am, and Kerri Chandler is slumped in an overstuffed lounge chair, exhausted but elated. All points of conversation, unsurprisingly, return to his father. Tonight is the first time Kerri has stood behind a pair of turntables since his dad’s funeral the week before. Joe’s presence is writ large and in bold script across the evening.

“The funny thing is, a lot of my friends are worried about me, like ‘Are you going back on the road too soon?’ And I keep saying to them, ‘I’ve got to jump back in to see what I feel like.’ I mean, it’s not ridiculous – I’m not doing a stadium, or something really big right now. These are all smaller gigs, here and Canada, just to touch the water and see what I’m thinking, ” he explains. “I need some kind of… I can’t say ‘closure’. It’s more that I actually need to find myself again.”

And while the moment is certainly a respectful one, it’s not solemn for Kerri. He’s not here to mourn Joe; he’s here to celebrate him.

“When I was at his house [making funeral arrangements] I found, under the bed, that first Acoustic Research turntable. I picked it up and sat on his bed, and I just kind of stared at it. I was actually almost frightened of it, because I wasn’t sure what to think,” he says. “You know, he was my biggest fan. He would always tell me, ‘Kerri, it’s like a relay race, [and] you didn’t just run with the baton, you jumped in a Ferrari and took off.’”

It should go without saying that being a DJ in the mid-1970s was to be at the vanguard of a burgeoning art form, one that had no rules or structure, never mind a discernable financial future. The goal wasn’t riches and fame, it was simply a love of the music. Not only was it incredibly rare to have a pair of turntables and mixers at your disposal, but the lessons his father taught were priceless.

“He told me this early on: Never pitch a record with strings or vocals, because it’s easy to tell. Always do it with a drum or bass — something short and stabby, because you can change it up gradually,” Kerri explains. The lessons were as numerous as they were invaluable: know your records; don’t play one style of music all night long; know when to speed up a pitch to get the crowd moving, and when to let them catch a breath to fetch a drink. He would take Kerri to other people’s gigs to show him what they were doing right and what they were doing wrong. These were lessons rudderless DJs would take years, if not decades, to learn.

“How you start and how you finish is the most important thing. It’s like a movie: even if it’s a great movie, if it ends like shit the whole movie feels like it was shit,” Kerri says of Joe’s golden rule. “So I treat it like it’s a living room environment – it’s not just me DJing, it’s all of us.”

The point is this: should you ever be so lucky to find yourself in a nightclub watching Kerri Chandler zoned out behind the decks, pivoting from working a break on the tables to moving over to the keyboards like a wild dervish, take a moment to register the history, and give a nod to Joe.

"I've stuck to my guns. I've never veered off to follow a trend"

“He always told me: you want to send people home singing. You want to send people home on the up, not on the down.” DJing, house music: Kerri’s been making people dance for 40 years; it’s been more than a quarter of a century since his first club hit, ‘Get It Off’. Most of his early contemporaries are long gone; others are staples on the calcified Dad House circuit. Very, very few are playing clubs like DC10 filled with the world’s coolest 20-year-olds while notching cover stories for international magazines. Kerri’s longevity and sustained relevance simply doesn’t happen by accident.

Rewind the tape back a little over an hour. It’s the closing minutes at Seattle’s Q Club, and Kerri is playing way past the 2am shut-off time. In fact, it’s gone 3am and he’s showing no sign of slowing down. He smiles at the dancing crowds taking it all in, working his Technics like a Renaissance sculptor working marble. Suddenly he jumps out of the booth and into the crowd, bouncing up and down as he sings a call-and-response with the crowd to his club staple ‘Rain’. It feels vital. Real.

“I’ve never had a lack of work, that’s what I can tell you,” Kerri says later on, describing how his crowds have (and have not) changed in his tenure. “I’ve stuck to my guns regarding what I’ve played and how I’ve played it, and I’ve never veered off to follow a trend. But there’s a newer generation coming in and discovering what I’ve done, so I guess it works in cycles.”

You can almost see the line of continuance, from his DJ Little Man phase to his Kaoz alias to now, a steady, constant rise in profile that has seen neither dizzying peaks nor terrifying nadirs. A career that began spinning disco migrated towards classic New York/Jersey garage, seeing him produce his first single and immediately signing to Atlantic Records. He established his Madhouse label in 1992, and moved to Italy where he cemented his status in the continent. An auspicious decision, as fever since, Europe has been a constant fountain of bookings and adulation.

And in this long narrative, his style has, of course, evolved – from early NYC house to the deep house sound ofd the 90s and early 00s, to his current fresh take. You can see how gospel informed his soulful take on the 4/4, and those rich vocals can be heard throughout his sets. But his style has also taken on a more modern tone, substituting those delightfully tinny proto-house drums with better production, bigger sounds that work in festival tents and temples like DC10 on his sub-labels like Madtech and Kaoz Theory. And perhaps what he does most masterfully is blend these newer textures with his classic deep house palette, using it all as a canvas to modulate and echo and dress with live piano and effects. No wonder a new generation is lapping it all up here at the Q, and across the globe.

Back in that W suite the clock starts to blink past 5am, our respective beds are calling, but we bring it back to Joe one last time before we break, asking Kerri if there was any single moment when his father’s presence felt most pronounced tonight.

Kerri puts his arms behind his head and leans back into the depths of his chair. “I’ve gotta say, ‘Lost In Music’ was probably the moment,” he says after a long pause. “I saw it pop up on my tracklist, and I wondered: ‘What that’s gonna sound like in here?’ And it instantly reminded me of my dad, and I was thinking, ‘I’m going to play it, because it’s one of his favourites. I’m going to see even how I feel about it. Is it gonna make me upset? Am I going to be happy? How are people going to react to it?’”

We can pinpoint the moment precisely: Kerri had started with a dub of Chic’s timeless disco classic, and then transitioned to the vocal edit – and the Seattle crowd went bananas. What we hadn’t realised was the track title’s poignant relevance.

“‘Lost In Music’ brings me back to a place. It’s like when you hear a record and it just takes you someplace you know, like one of your memories. Every time I think of that song I can see him singing it, snapping his fingers. He had a way of doing that, like one of those lounge singers, but with a big smile on his face. He was a big joker. But of all his records, he really, really loved that one.”

Kerri pulls out an iPhone and starts scrolling through millions of photos. Finally he lands on what he’s looking for and plants his finger down: an image of Joe, dressed in a killer white suit: half Mavin Gaye, half Scarface, all glowing fucking charisma. “He could create something huge from almost nothing,” says Kerri. “The party didn’t start until my dad got there. He had a way of transforming any situation into something that was just unheard of.”

He continues looking at his phone for a moment in silence. Outside, Seattle is lost in inky blackness: the clock in the W suite creeps towards 6am. “‘Lost In Music’ got everyone a little bit nostalgic,” he sighs, at last. “And it made me realise that music is timeless. People live their moments the same way I did, and now they probably have their own memories about how they enjoyed it. And I have mine.”