Features

Features

A short history of boundary-breaking South Asians in the UK

Haseeb Iqbal spotlights the underreported impact of influential South Asian pioneers in the UK

As a South Asian who has spent the past two decades growing up in London, I have never struggled to establish and deepen my cultural interests in this ever-bustling metropolis. There has always been so much that I can relate to and there constantly seem to be new and exciting energies presenting themselves via different eye-opening art-forms in all corners of the city. However, much of the culture that has presented itself to me across my life been a product of either white or Black heritage. For some reason, Brown culture has always been harder to find and less excitingly received by those around me. This was something I didn’t appreciate until only a couple of years ago, at which point I realised that there was a clear and alarming void in the knowledge I had, and pride I felt, regarding my own heritage. I believe this had been due to a couple of reasons: firstly, there being a lack of accessible, and rounded, representation of people from South Asia on a mainstream scale in this country throughout my upbringing. And secondly, a lack of both positivity and balance in the way that my culture was taught to me in school, as well as presented to me via various lenses of the media. It was this lack of positivity and depth that offered space for the negative, ill-informed stereotypes of what a country like Pakistan represented to garner more momentum and inform those around me, as well as myself too. Suddenly, a complex, multi-dimensional narrative becomes distilled into a spectacle of lazy simplicity. Positive histories become forgotten and people become influenced by careless sentiments rather than factual information. An entrenched ignorance grows and any sense of coherent dialogue becomes harder to achieve because of how we have been conditioned to treat a culture.

Read this next: Exploring identity: What does it mean to be a South Asian in the UK in 2021?

The arts continues to be a crucial space where stories, that should have been told in school or spoken about in mainstream media, can be explored and shared, offering an imperative antidote to the misinformation we so recklessly seem to consume. While social media and technological advancements have in many ways been emblematic of misinformation and an incoherent dialogue, they have crucially allowed a resistance culture to grow in recent years, subverting the effectiveness of mainstream media sentiments, and allowing alternative stories and perspectives to be illuminated and interrogated.

Observing the recent momentum that South Asian underground culture has been receiving through collectives such as Daytimers feels incredibly welcomed. It is brilliant to see platforms such as NTS, Boiler Room and Mixmag, and spaces such as Brainchild Festival, offering our community the capacity to build momentum and exchange our culture, and the stories that bind it, with the rest of society. The ability for us to be in this position, though, certainly didn’t come overnight. It is a privilege that is thanks to many who came before us and broke down those barriers to create more of the freedom that we can now enjoy. While we are a part of extending that freedom and fairness for those who follow us, we must turn our minds to some of the first South Asians who broke down key barriers in the UK. The impact of these figures - many of whom made their mark before the partition of India, which formed Pakistan and Bangladesh as countries in 1947 and 1971 respectively - deserves to be honoured.

Read this next: A deep dive into South Asian electronic music

In my research, I was fascinated to come across an Indian woman called Cornelia Sorabji, who lived from 1866 until 1954. She was the first woman to study law at Oxford University, doing so in 1889, significantly helping pave the way for women in the UK to enter the Bar in the years and decades that followed. One of the most important developments that she made was protesting the university’s decision to not let her sit exams alongside men. She saw this as an injustice to women across society and after drafting a written petition, was granted permission to sit her exams in the same room as others. This became a huge step forward for women’s rights within higher education in the UK and remains a relatively unheralded snapshot of British-Asian history.

Another key figure was the Brighton-born physician of Indian, English and Irish heritage Frederick Akbar Mahomed who was renowned in the mid-late 1800s. He was responsible for noting that high blood pressure led to kidney damage and other illnesses, outlining that healthy people could suffer from this - a diagnosis that was ground-breaking for public health in England at the time and ever since. He was also the grandson of Sake Dean Mohamed who was the first Indian to publish a book in English. He was notably respected for introducing Indian food as well as shampoo to European society in the 1700s. His restaurant, the Hindoostane Coffee House, was the first Indian eatery in England, opening in Marylebone, London in 1810. Originally from Patna, Mohamed was born into a Bengali Muslim family and his influence on British society was irrefutably instrumental, however, his role seems to be forgotten from many history books. The magnitude of his impact is marked by the fact that he lived to the ridiculous age of 91 – a feat totally unheard of for somebody who passed away in 1851.

Read this next: How Asian Dub Foundation's stand against racism connected generations of British Asians

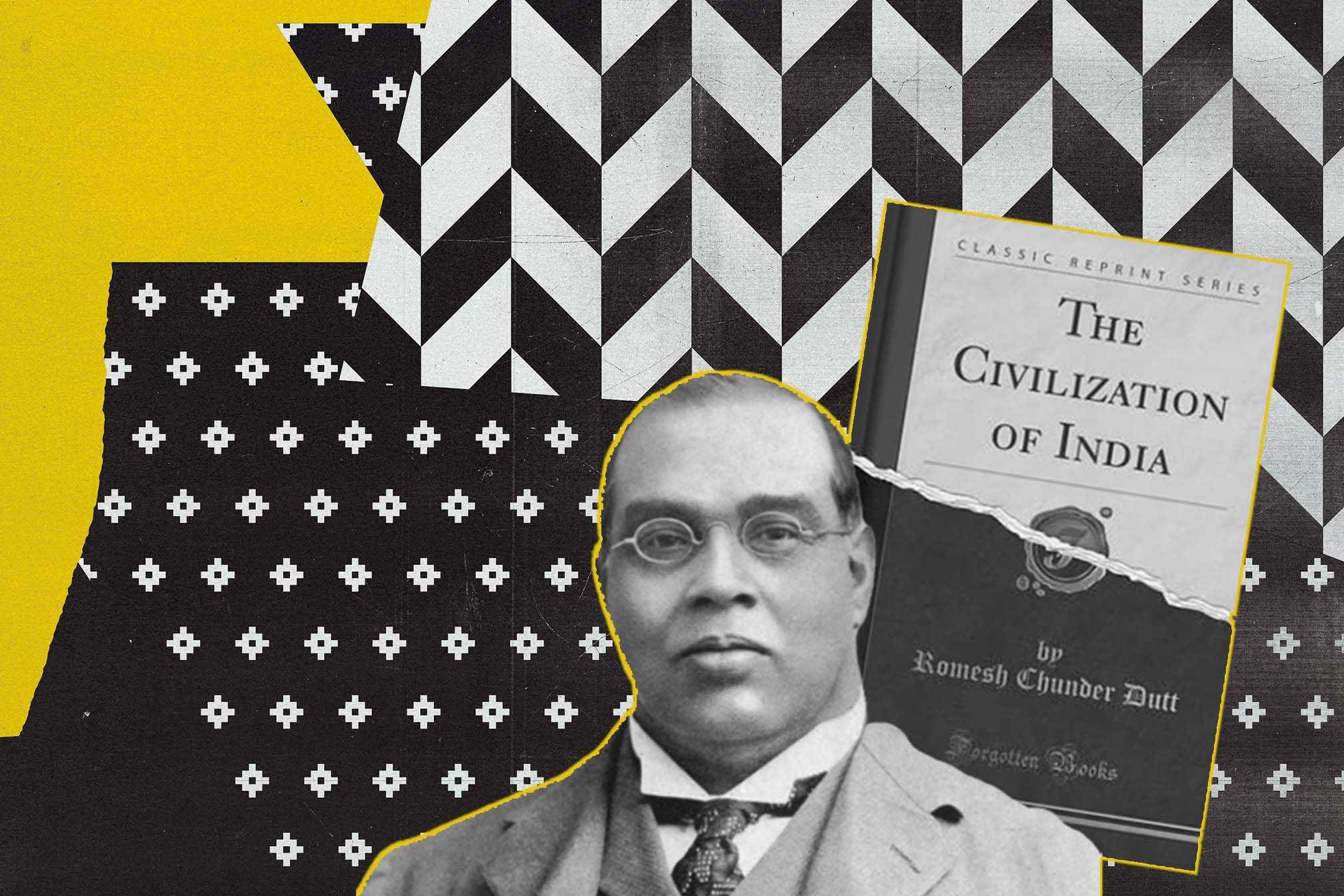

Another exceptional South Asian figure who made his mark on British society was the economist Romesh Chunder Dutt, who studied law at University College London in 1868, becoming the first Indian to be appointed a district magistrate in 1883. Immersed in law, literature and economics, Dutt wrote various seminal works. However, his most influential piece was an economic analysis on the de-industrialisation of Indian society under British colonial rule. Alongside Dadabhai Naoroji, who was the first Asian to be a British MP, Dutt's work coined the ‘drain theory’ which articulately illustrated why and how British colonial rule directly drained the economy of India, refuting the ill-informed, commonplace argument that colonialism helped boost India’s economy. A large part of this focused on the negative implications the railways caused on India’s domestic industry.

It feels rewarding and exciting to read and write about these South Asian figures who all had remarkable impacts on British society prior to even the 1900s. However, it feels equally disconcerting that these monumental people have been so forgotten from the narrative of this country’s history. I certainly was never told about them and I wonder who is aware of their impact. We must continue to share stories with the momentum that we are currently seeing; it feels really special to see repressed narratives having light shed on them after so long. It is vital that we maintain these webs of communities that offer a safe space to speak, listen and reflect on stories that form a key pillar of this country’s fabric. We must hold dear positive stories which uplift and inform us; stories and histories that are a part of us all - we have never needed them more.

Haseeb Iqbal is a writer, DJ and broadcaster and the author of Noting Voices, follow him on Instagram