Features

Features

Daniel Vangarde: "The Disco Demolition was homophobic, racist and stupid"

In one of his first interviews ever, the legendary producer and songwriter talks pride in his son Thomas Bangalter's rebellious approach in Daft Punk, Grace Jones and loving imperfections

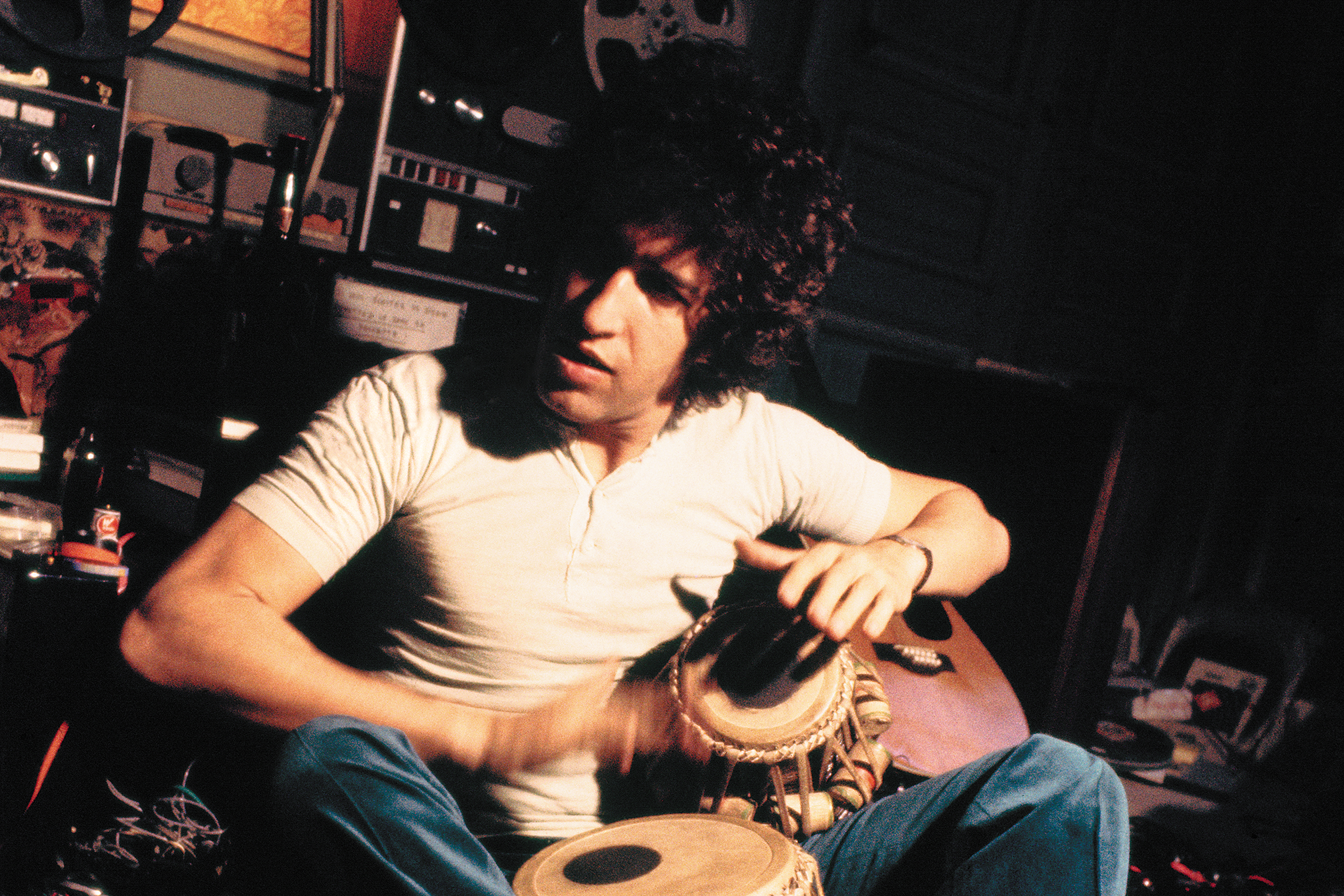

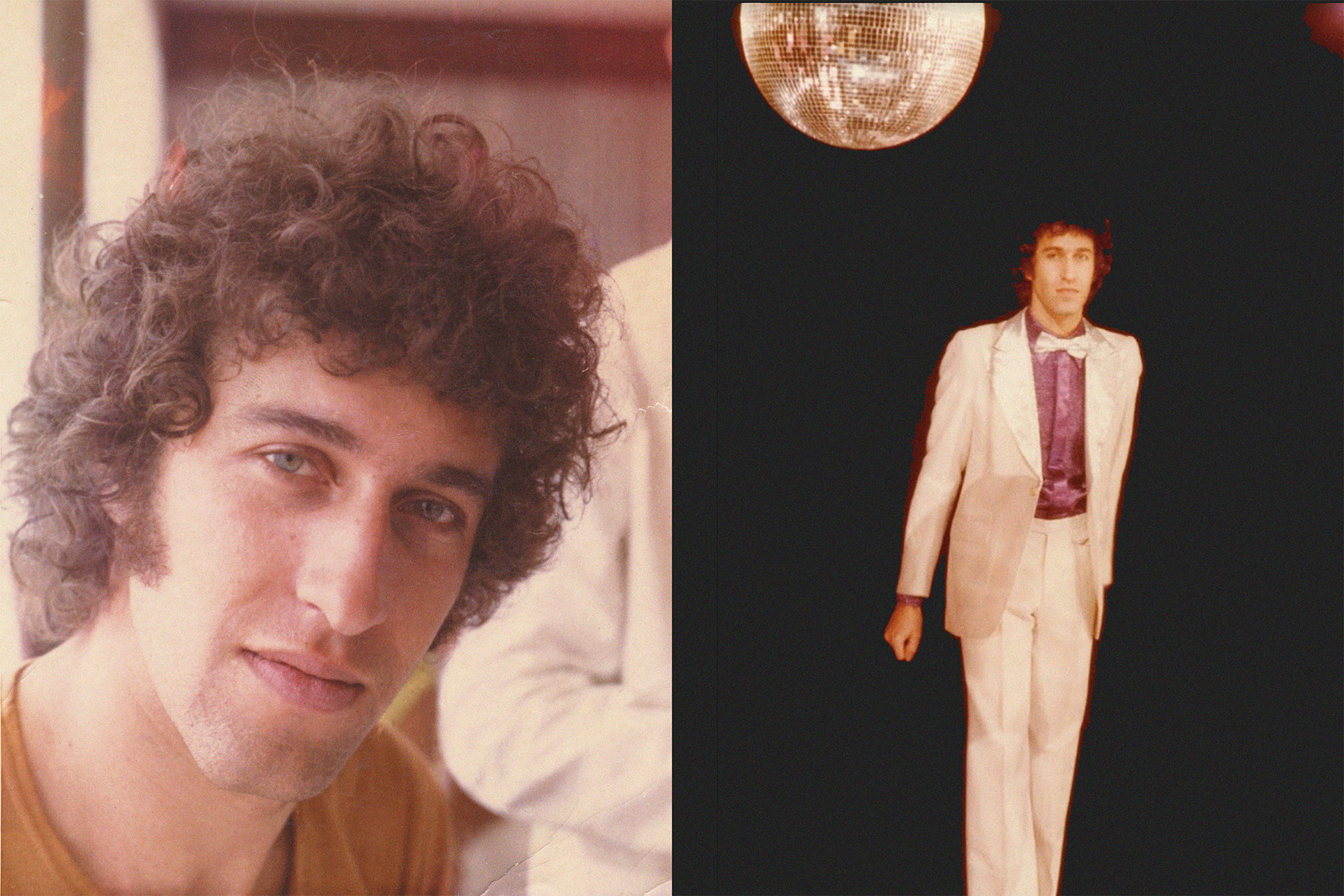

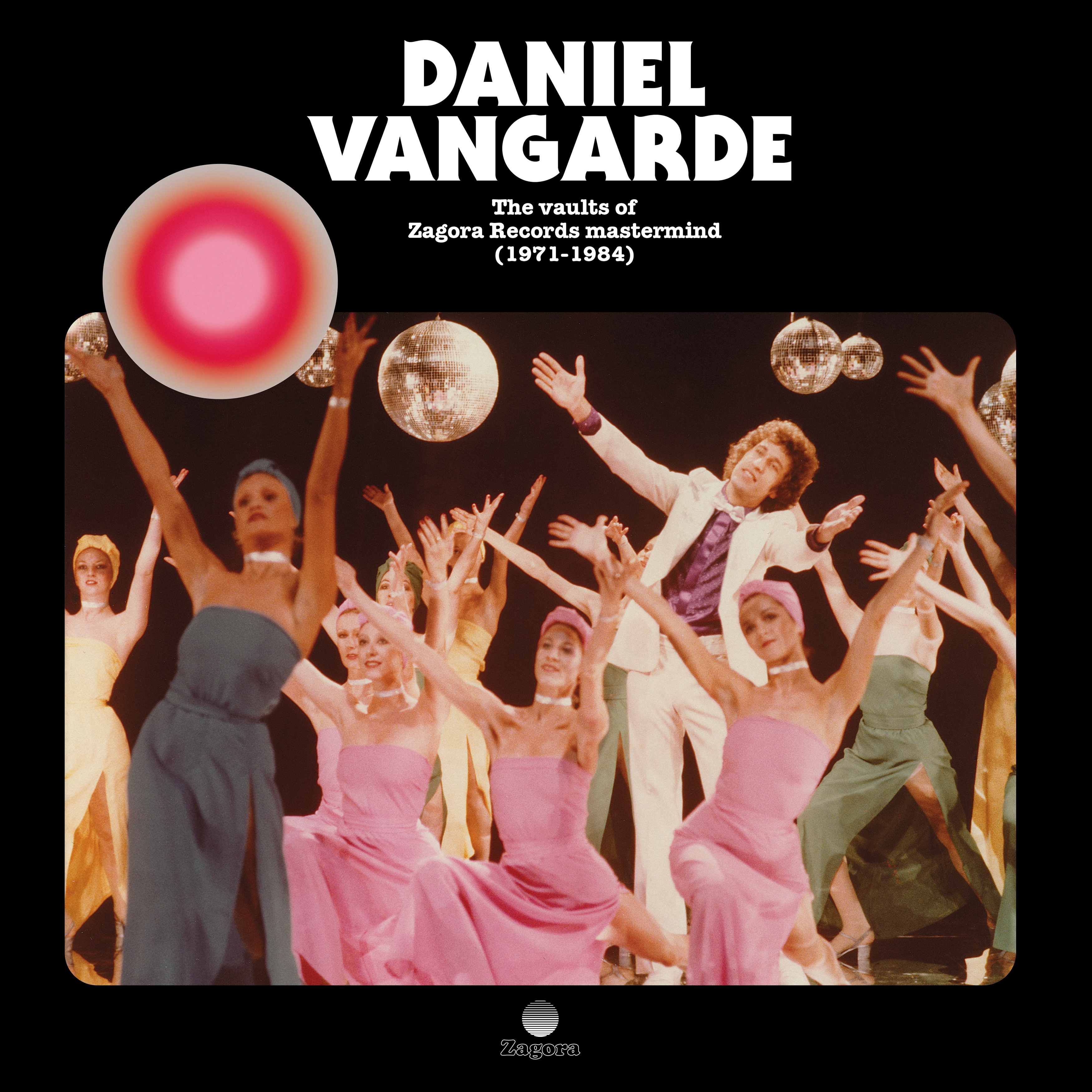

Despite having contributed to some of the disco era's most iconic sounds, Daniel Vangarde - real name Daniel Bangalter - hasn't been one to speak much on his experiences. Across three decades, the French producer and songwriter was the brain behind genre-defining records such as ‘D.I.S.C.O.’, The Gibson Brothers’ ‘Cuba’ and Black Blood’s 'Aie a Mwana’. Collaborating with some of the biggest names in music across the '60s, '70s and '80s to create timeless records still spun on dancefloors to this day — Vangarde would also release music under his name and alias’ Starbow and Who’s Who. His latest venture sees him reflect on his vast catalogue of hits with a three-sided album titled ‘The Vaults Of Zagora Records Mastermind (1971-1984)’.

We catch up with him, bathing in the sun that beckons into his tropical garden in a remote area of Brazil, Vangarde smiles as he says in an amused tone: "I never did interviews, ever". He modestly adds: "It's very funny, It's a surprise to see that people seem to find things I did 50 years ago interesting." Tranquil and relaxed, Vangarde is ready to reveal all on his beloved Zagora Records, his encounters with some of disco's biggest stars and indirectly passing to dance music baton to his son, Thomas Bangalter of Daft Punk.

Read this next: Father of Thomas Bangalter, Daniel Vangarde announces new disco album

So how does it feel for this disco mainstay to be reflecting on Zagora Records enviable archive 50 years on? What does he think of the modern disco continuum? And was Studio 54 really as crazy as they say? We asked Daniel these burning questions, and more, below:

'The Vaults of Zagora' is a collection of your work between 1971 and 1984 — what was the decision behind releasing the album? why now?

I sold [Zagora] to Because Records, I'd been working with them for 12 years beforehand and they'd had distribution rights of my songs. A few months ago, they came to me and said: "we'd like to release some of your work that was maybe overlooked in the '70s etc." They made a list of 20 tracks... I had to go to YouTube and listen back to make sure I was actually the producer of the options they'd chosen [laughs]. I never listen back to music, except if they are hits and I hear them on the radio. When I listened back to everything I was amazed at how good the songs sound, there's a real diversity and I have some fond memories of creating them. I then said yes, I also agreed to do interviews... I never do interviews. I started three weeks ago, so far, I really like it. [Laughs].

How come you don't listen back to your old work?

I don't know. I like to go upfront and to walk, to do something new. I don't want to be influenced by what I've done before, I don't want to repeat myself. This is why, when I make music, I never listen to other music. I know for some people, they listen to everything that is around and pull influences from it — I never did that, I always tried to find influence in other places. It's obvious I get influenced, but I don't get influenced by other styles [of music].

You mentioned earlier that a lot of memories came to you when you were listening back to some of your work featured on 'Vaults of Zagora' — any you'd like to share?

I had memories from every track! But for one of them, 'Palace Palace' — I was coming back from a rollerskating disco in New York. I like roller skates, so I was dancing using them. When I came back I wanted to make a track about dancing in roller-skates — I used this loud whistle like they used to have at the discos in New York and a vocoder, which at the time was a brand new instrument. I've always been into technology. So I spent a lot of time with the vocoder, in that track I used my own voice but you can't recognise it, I'm saying "Do you want to dance?". I was fascinated with it. Two years later Laurie Anderson made the track 'O Superman' with a vocoder, it was a hit! My song was not a hit. [Laughs]

Doesn't have to be a hit to be great!

No, you're right. When I create a song, I like to have fun and I like to make the best thing I can possibly make. I like to enjoy the writing and recording and have a good time. If after that it's a hit, then it's just a plus. I will say though, when you create something and you can sometimes have an emotion or a sensation around it, you can feel in your stomach that it will be a hit. I know when I've made something strong, and I feel that other people may feel the same. But if it doesn't happen and have a good time, then it's worth it.

How was it to bring this record to life? was it nice to reminisce over your time at Zagora?

It's nice, and very funny. I'm doing some media now and I had an offer from French television to do something with me live over Zoom. You know? Me! I think it's crazy! Because I was never involved in media all my life. I did my first interview with Radio Nova in Paris three weeks ago, but I'd never done any of this before... I didn't want to.

What has changed your mind?

Because the record company asked me [Laughs]. I'm not doing new things now, so it's [talking about] something from the past. I'll tell you the real reason all of this is funny... when the label asked me to do interviews I said: "No, I have never done it and I will not do it." But I talked to my son Thomas [Bangalter, formerly one half of Daft Punk], and he said "Why did you say no!?" and I said "Because, I never did it!" and he said "Well, why don't you do it now?!" and said "Fine!" So I changed my mind.

Well, we're glad you did! So the album touches on your projects such as Whos Who, Starbow and your collaboration with The Gibson Brothers, etc. How important have collaborations been to you in your career?

I think collaboration is everything... you have to relate with people. Working with good musicians is exciting, when you record live and you do a few takes — suddenly, everyone [who is in the studio] will get that feeling which take is best. You'll have the technician coming round and going: "Yes! this is the one!" It's like cinema, sometimes directors will do 30-40 takes to get the best version of the scene. Charlie Chaplin would do 70 takes sometimes. My first collaboration was with Jean Kluger and we created quite a few hits. He taught me to write songs, he's a little older than me, and he would always say: "You don't learn in schools, you learn by listening." I've lived by that I think throughout my career. I like to use a recording studio, because even if you're alone you still need an engineer or someone in there to help you. When you record live, you can have unexpected things happen. You can programme, but you don't have surprises — it's just about layering. There can't be any surprise in layers, it's all definite from the start – you're the prisoner of the tempo and rhythm. If you make a mistake, you can get rid of it... but that is terribly boring.

So you want more mistakes in music?

If you listen to all of the great records from the '60s and '70s they are full of mistakes, but you don't notice – when the tempo switches it's exciting! If the volume is off slightly, it just makes the record better – it comes alive when people come together. I think the new recording technology isn't as exciting, but the accidents have to come in processing. I used to work at the console in a studio and when you have a lot of faders you can still make little mistakes when you're mixing. But when you're using automated processes, that you can listen back to and correct — you'll correct everything. I stopped using it, the more you correct the flatter it becomes. One thing I will say about technology, is that the CD killed the music. You know, [sings the hook to 'Video Killed The Radio Star']. I met the guys that wrote that song actually (Trevor Horn, Geoff Downes and Bruce Woolley) when I was when I was releasing the Gibson Brothers with Island Records in London. But yes [sings new version: "CD killed the music"].

Read this next: 30 photos that prove disco balls rule the world

Can you tell us about some of your favourite collaborations?

I worked with very few artists really, but the Gibson Brothers and La Compagnie Créole — I worked with them heavily. I was involved in producing the songs, the look, the shows. At the time it was good, when it was not good anymore then I stopped it. Creating songs, you can only do it if the relationship is good. I had good relationships though, like the track I made with Black Blood — 'Aie a Mwana', but that was only one recording session, one time.

You said then you were involved in the look, can you tell us about that?

I think the look is important. When we started with the Gibson Brothers, they were French but they wanted to have that American look. They came to the studio with Chevrolets, every three months they'd change cars — always second hand, but different cars. Whereas I'd be turning up to the studio with my old Volkswagen that lasted 20 years. [Laughs] The first look they had was these pink jackets with mirrors, they looked like stars. I bought those jackets.

Can you give us any tales from the club in the height of the disco era? Was it as crazy as everyone says?

I wasn't really into nightclubs to be honest. I'd just go to play acetates of what I was making and see how it sounds compared to International productions that were getting played in the club. One night, I was at a club in Paris listening to my records and as I was leaving I heard this incredible record — I raced back in and asked the DJ: "What is this song?" It was from Chic, it was the best sound I'd ever heard. I searched it up and it was made at Power Station (iconic NYC recording studio now part of BerkleyNYC), and two weeks later I travelled to New York and I was mixing in the studio. I met Nile Rodgers while I was there, at that time he was very much involved in the studio, and we did a remix of the Gibson Brothers 'Que Sera Mi Vida' — it was fantastic. The same tape on the equipment at that studio sounded different, it looked like the same equipment and speakers — but the truth is there were five engineers who worked there and they were always looking to upgrade machinery they had. It was extraordinary, It was like I'd never heard it. It was a hit! I think it's because of the sound.

I also met Carly Simon in that era, she was wonderful. She used to come to the studio when I worked there. We became friends, I loved her as a singer. She invited me to her house in The Bahamas, but I was married at the time so I didn't go. [laughs]

You really loved the music.

I loved the sound, the arrangement, the strings, the brass — I thought it was beautiful. The Disco Demolition Night in 1979 upset me a great deal, I thought it was stupid, homophobic and racist to say that disco "wasn't cool any more" — they wanted to target music created primarily by Black and gay people. I made a track called 'D.I.S.C.O' in reaction to that. I wasn't Black or gay, but I felt like I needed to stand against that movement... I wanted to show that it wasn't dead and those people were wrong.

Did you ever make it to Studio 54?

Yes! once. I was with my friend Chris Blackwell who was the head of Island Records at the time. I actually got in because we were with Grace Jones, she was doing a show actually — that place was crazy, yes. She entered from the back of theatre, because Studio 54 had a theatre upstairs, and the room went black and suddenly she was on stage — then the lights went off and she was suddenly somewhere else. They had lookalikes hired to appear everywhere to confuse us, It was amazing.

How do you feel disco has changed from when you started producing to now?

Disco is dance music, and I don't think dance music ever changed. It goes out of the speakers and people dance, it became techno music, house music — more or less it's the same thing. I think putting labels on music is the work of record labels and the media. It sounds different and it's made different, but people get together and dance to it the same as before.

Do you think disco has had a lasting impact on the music coming out of France since your era?

Yes. As I said, there's a continuity. The people who made music in the beginning of the '90s, they heard disco. They grew up with it. It was popular music, when they'd join together for parties they'd play disco. I don't know how it is in England, but even now in France on big occasions we still listen to disco. I think at that time, we used to listen to everything that was popular... but now it means that those songs are all well known, everyone loves them and they can sing-a-long.

Did you ever think you son Thomas would be a producer himself? Was he around you making music a lot as a child?

I don't think I ever influenced Thomas voluntarily. But it's normal that he was around what I was making and listening to, something must have sunk in... probably. I do think it's very different, maybe the last album where they played with musicians and were using technology from the '70s alongside the modern stuff — it sounded a little more similar to what was around when I was making music. He was never really in the studio with me though, he maybe came once or twice? I don't think he was interested to be honest. His productions have nothing to do with me at all. But I think that's a good thing, as he would have learned to do it the way I do it — to mix in this studio setting, and he would never have done what he has done with his friend. It was totally new, because they didn't know what they were doing. If you go to a recording school, you don't make this kind of music because you learn a formula —what they did was forbidden. They would put the sound on maximum, cut, they'd do so many dramatic things... you don't do that learning how to "produce and mix." Fortunately, he wasn't in the studio with me.

Read this next: History revision: The art of the disco edit

How did you react when he began producing music? Did it make you proud to see Daft Punk's success?

I was surprised because it was totally new, I was a little upset because I thought: "All the young people are going to create this kind of music. No this is not the dance music I make, It's not my time any more." I used to make songs, but this isn't about songs it's a completely different type of experience. It took a little time to get used to it, but after a while I thought it was great and new — so rhythmic. I didn't understand how it was done. I was proud and very happy for them. If you can make music and enjoy it and make a living out of it, it's a very big privilege. If you have success it's even better. But it's important to do something you like, but also eat and travel with the money you earn — it's fantastic.

What do you hope people take away from the collection?

I was talking to somebody today and they said: "The sound is great." I haven't heard the vinyl yet, they went out today. I'm very happy with this feedback, sound has always been an obsession for me — the reason I worked outside of France so much is because I wanted to use the equipment and sound recording technology available on US or UK records. I also hope that in 50 years from now people will still listen to my music, some songs are already 50 years old [on the record], y'know?! It's already very good going [laughs]. I never imagined it would be like this, so if it goes another five decades and people are still listening I'll be very happy. I won't be here, but that will be nice. [Laughs] I'm joking, of course!

‘The Vaults Of Zagora Records Mastermind (1971-1984)’ is out now digitally on Bandcamp and on double vinyl LP and CD.

Becky Buckle is Mixmag's Video and Editorial Assistant, follow her on Twitter