Culture

Culture

How the fall of the Berlin Wall forged an anarchic techno scene

It's been 30 year since the Berlin Wall fell — and the party hasn't stopped since

For almost three decades, a brutish man-made barrier divided the city of Berlin. The German capital was split between East and West, in the hope of divorcing a capitalist ideology from a socialist enclave.

This metropolitan membrane stood strong from August 1961 until November 9, three decades ago, when it all came down.

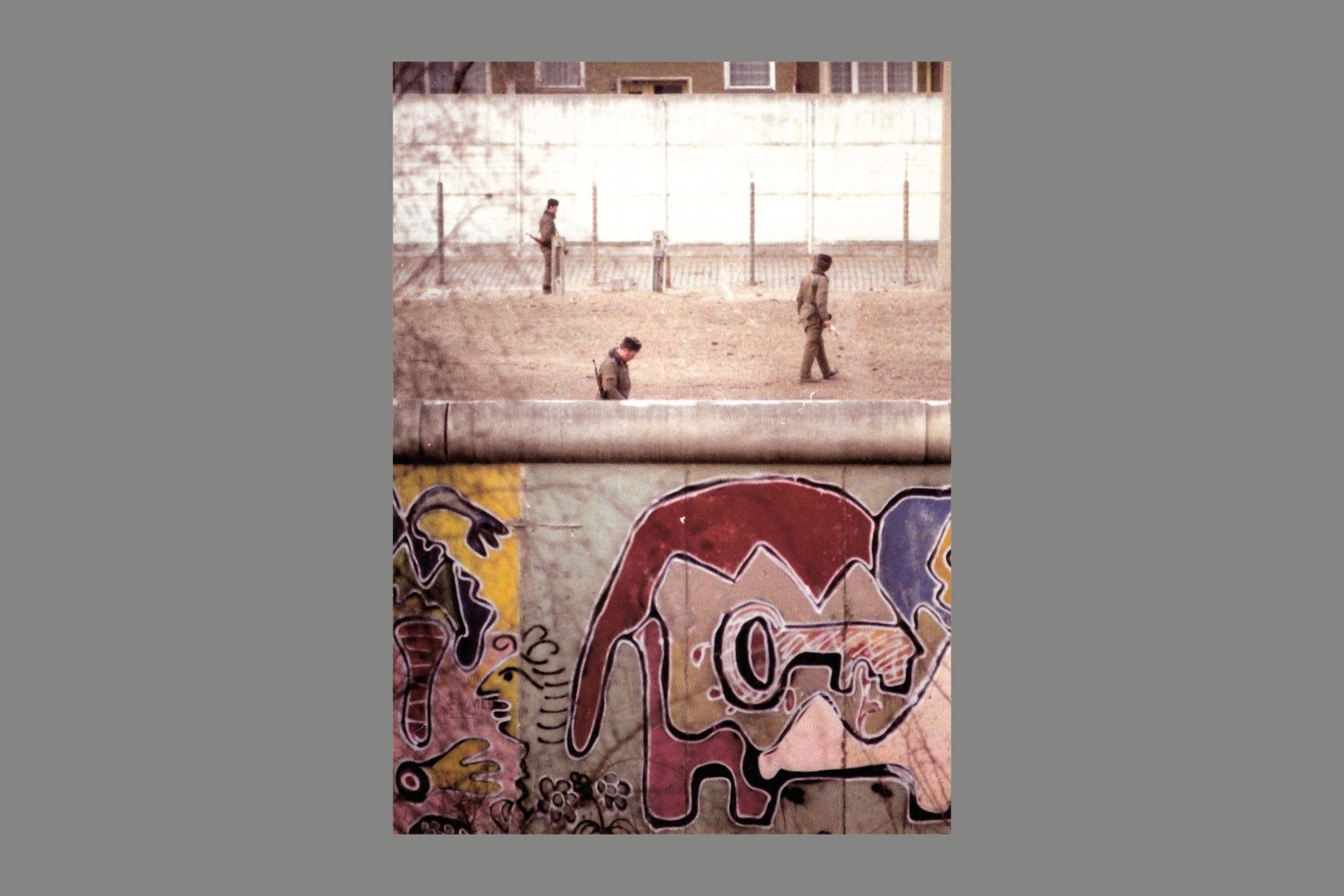

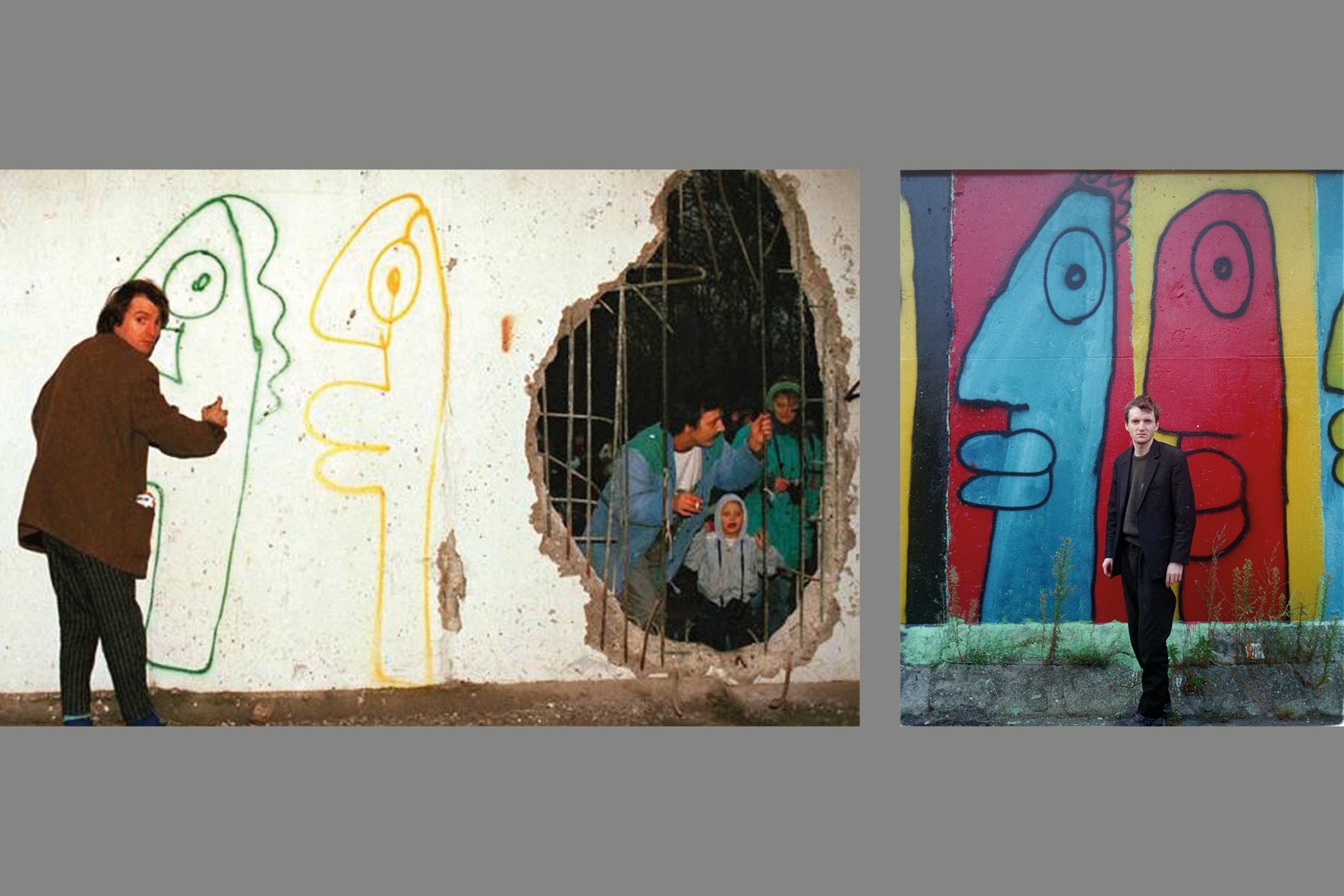

[Photo: Mark Reeder]

What followed was an era of political and cultural unification. East and West Berliners were now Berliners, free to roam as they please. Clusters of previously corporate-owned buildings were rendered abandoned around the fallen wall, housing the birth of an anarchic electronic music scene that would go on to garner eminent status around the world.

Read this next: This new photo book captures the raw energy of Berlin's 90s techno scene

In light of this anniversary, I’ve spoken to those who lived through this period of change to gain an understanding of how, and why, political unrest can prompt the production of such powerful music.

Resident at Tresor & E-werk and worked at Hard Wax records DJ Hell

“In the ‘80s we believed in a so-called "no future generation”— Berlin was a Mecca for outsiders, punks and different-thinking people. Early ‘80s German punk and new wave music was becoming very strong — it was the first time innovative experimental music was in the spotlight with German lyrics. The music scene was very radical at that time. Lots of people in Berlin weren’t fitting into society and created their own world.

“I was in Bavaria when the wall fell. It definitely helped to grow the scene. Suddenly there were thousands of young people from the former GDR celebrating their freedom.

Read this next: DJ Hell in the Lab NYC

“Techno music in Berlin was political and totally against the system. Most places or clubs had no license or any contract, so it was all illegal — everybody could do it with a sound-system and some DJs. The alliance of American techno producers and DJs was born at Tresor — they booked DJs from Detroit, Chicago or NYC. The music was new and revolutionary. Underground Resistance (Jeff Mills, Mad Mike, Robert Hood) had a big impact on everybody in Berlin. The Berlin-Detroit connection was very strong and influenced everybody involved.

“East and West people were creating a new musical and political haven of electronic music and nightlife which today rules the world of techno. Techno was exploding in Berlin and the unification took force all over. East people became DJs, bouncers or dealers, and brought in a wave of unstoppable power — the party hasn’t ended since 1989.”

Member of electronic duo Terranova Fetisch

“I was born here, and after spending time away, moved back in 1979. Berlin didn’t have a Johnny Rotten or Mick Jagger, but it made up for it in its musical technology, with interesting bands like Malaria — although I did in fact meet Iggy Pop and David Bowie when I returned to Berlin.

“In 1988 I moved to London, which is where I was when the wall fell. My friends in Berlin told me that East Berlin was very claustrophobic before this

“I didn’t see a musical difference between people from East and West Berlin – I just saw people who were into electronic music and those who weren’t. In nightclubs, it was as if nothing ever happened.

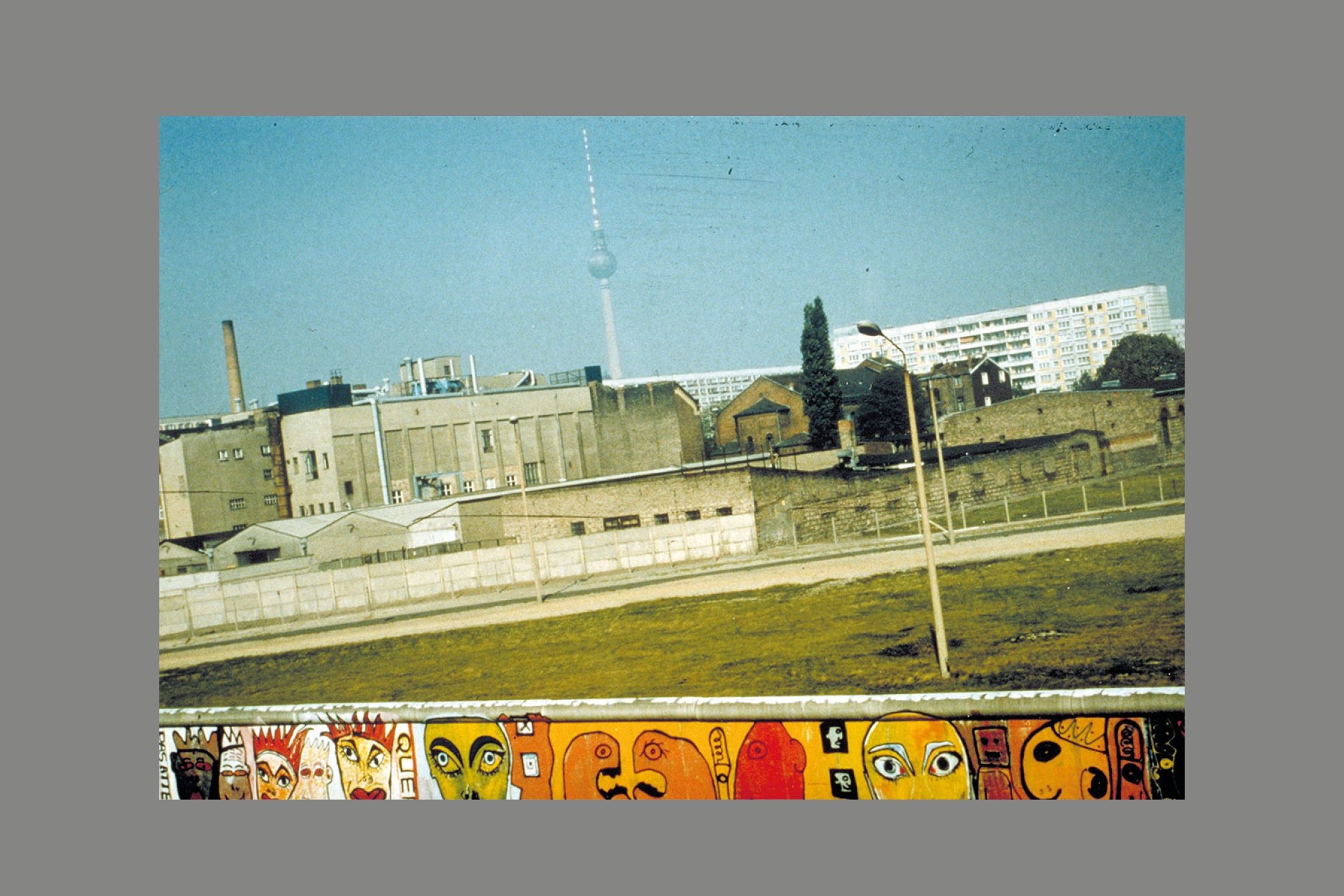

[Photo: Mark Reeder]

“After the wall fell, you could go out without a penny and it just worked. There were no bouncers or rules – anything kind of went. You could just start something.

“Those responsible for Berlin’s scene after the fall of the wall are Tresor and their Detroit connections, Westbam, Gigolo Records, Kompakt from Cologne and Planet club (which is, to this day, one of my favourites). I think Berlin wouldn’t be Berlin without all the foreign people who live here.

Read this next: Politics and dance music are intertwined and there's nothing you can do about it

“Politically, I’ve always been against government. For me, anarchy is about deciding who is responsible for what, and if they fail you, they lose that position. The politics of unity and interaction would be the politics of nightlife."

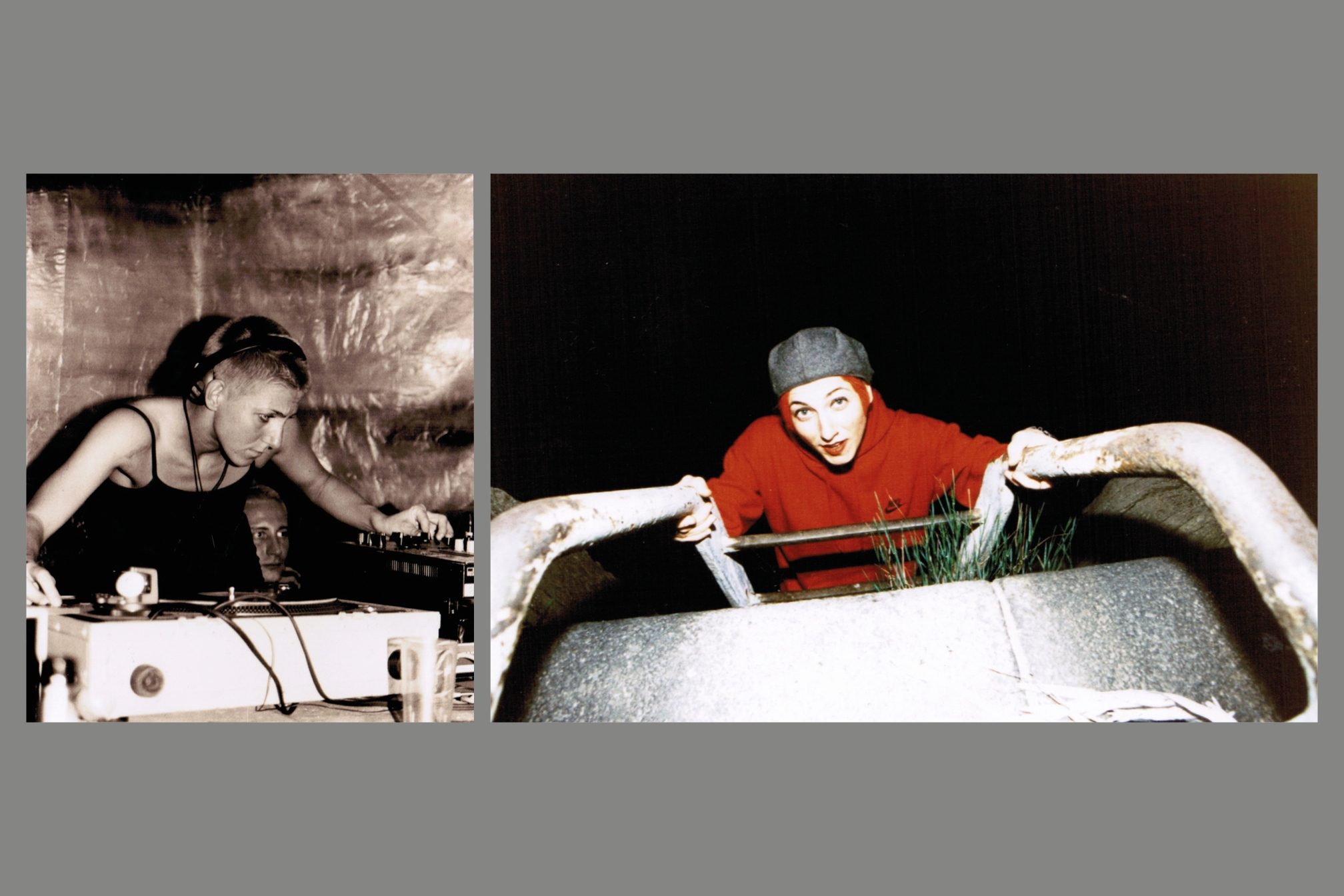

DJ and former resident at Tresor & E-werk Ellen Allien

“It almost felt like living in a cage. When the wall came down, I did not believe it. I cried like crazy, it was like a dream. It was a celebration of freedom, like somebody coming out of a prison – I explored East Berlin straight away. It was so different.

“I started playing at Tresor in around ’96 — Tresor is my godfather, my mentor. Acid house actually came first from the UK and America. It was the new underground sound. Then that sound became more minimal, harder and faster, and techno started.

Read this next: Ellen Allien takes us on a tour of Berlin to show us why "it's the best city in the world"

“Young people from East and West wanted to meet each other, and we celebrated our togetherness in the club - we became one. Without the divide in the first place, the club scene would not be what it is today. It would not be as compassionate as it is now. Berlin club owners were really passionate – they had ideas about free-form living. They loved what they did – it was a lifestyle. This energy comes from the political situation.

“Clubs like Planet and E-Werk were really important for the scene. Kiss FM was also really important – there was a mixture of pop, techno, drum ‘n’ bass, breakbeat. Monika Dietl, in ‘89-early ‘90s, was super important. She played all the hot shit on her radio show; she was the angel of the scene. I remember asking my boyfriend “What kind of music is that!?” She had a fantastic selection."

First artist to paint the Berlin Wall Thierry Noir

“I came from France to Berlin in 1982, and everybody I met was an artist. I started to try to prove myself as an artist there. After two years, I started to paint on the Berlin wall – it was such a melancholic life. It was an emergency act, and it changed my life.

“Punk and new wave had similarities to street art. All the punk girls had rats on their shoulders, and they changed the colour of the rat to match their hair each week. It was very hardcore. All those guys live with their heart – musicians, painters, designers – that movement was very strong in Berlin.

“When the wall came down, we realised there were creatives in the East, too. The two groups merged together.

“I think art accelerated the fall of the wall – it showed the world that it’s not normal to have a big border like that in the middle of the city. This mutation of the border was shown on TV, and the government had to react to it. It was very important that it happened.

“I was happy when the wall fell – it wasn’t an art project for me. It was great to see it gone. The scene was so strong. We were underground fighters all together.”

DJ and founder of Love Parade Festival Dr. Motte

“I’m a born Berliner – I grew up in a city surrounded by a dark age. As a West Berliner, we felt somehow ‘cosy’ – a big city with lots of space, but not many people living there. We didn’t focus on the wall that surrounded us, we focused on having a good time. To me, a wall was what characterised a city. I never felt locked in.

“Berlin nightlife had no curfews after the war, and because of this we had a lot of people who wanted to have their freedom rather than go to the army. We wanted to have our liberty, our free spirit. West Berlin was filled with artists, painters, musicians and writers. It had a similarity to the way of life in New York.

“When it came to Love Parade, I was together with an American girl called Danielle de Picciotto. We talked about how we wanted to create a Mardi Gras-type event: a street carnival. My friends had been telling me about underground illegal parties in English cities like London, Manchester and Sheffield – about how somebody just switched on a ghetto-blaster and started dancing in the street. This is what Danielle and I liked. Our solution was to put on a dancing demonstration march, and when it happened it gave me goose bumps. It was initially quite an esoteric event; we wanted the music to last forever, and this, with the power of the ecstasy – I’ve never felt anything like it before. Ecstasy was the drug of togetherness.”

Native New Yorker, worked the door at Planet Club Mac Folkes

“I considered Berlin, then, to be a backwater outpost for draft dodgers, gays, punks, artists and crazy people. So somehow, I fitted in, but I did miss the opportunities for glamour that were offered in NYC.

“The music scene gave the youth something they could build together and take equal ownership of."

In response to being asked what it was like to be homosexual at that time:

“Berlin, for me, has always been a free, open and liberal city. As a so-called West Berliner, I didn’t really feel a freedom change. I am fairly certain that if you posed that question to an East Berliner you would get a very different answer.”

Upon returning to Berlin in 1988:

“Little did I know that the geopolitics of the world would shift, and I would somehow play a small part in the resurgence of Berlin. Several months later the wall would fall, techno took its grip on the youth, and as they say, the rest is history."

[Photo: Mark Reeder]

Founder of the first techno/trance label (MFS), protagonist of Lust & Sound documentary Mark Reeder

“I went to Berlin in 1978 to search for records, and found this totally fascinating, unknown place – especially the East: nobody went there. I discovered this fledgling, wannabe punk-rock scene. You weren’t allowed to be punk – they saw it as the failing of capitalism, and they didn’t want people to think that communism had also failed.

Read this next: Not dead: How punk inspires dance music's innovators

“I had access to all this Western music that those from the East could only dream of, so I recorded my record collection and smuggled it into East Berlin. In the eyes of East Germany, I was considered ‘Subversiv Dekadent’. They were intrigued as to what my agenda was –- but I just wanted to alleviate their misery.

“West Berlin was avant-garde – creatives, transvestites, gays and others could live a normal life there. The scene that I discovered was one of expression –- the mindset was radical. The idea of a dual city definitely spurred bands’ creativity.

“Joy Division elected me as their representative to sell their records in Berlin –- I’d go to the shop that Gudrun Gut worked at to sell them. I ended up becoming the manager of her band Malaria! and travelled around Europe with them. Soon after, I became the sound engineer of Die Toten Hosen, Germany’s leading punk band, who I smuggled into East Berlin for an illegal concert disguised as a church service. This created a whole ripple through East Berlin of kids who wanted to be in punk bands. Prohibited music, like illegal drugs, had a kind of natural allure to it.

“In 1989, the band Die Vision asked me to produce their album – I was sat in a studio, as a Westerner, while East Berlin was falling apart all around us. We finished recording on November 2, and on the 9th the wall came down. It made me the last Westerner to produce an album in East Berlin.

“The city that we left on November 8, 1989 was not the same city we returned to. Berlin was suddenly freed up of war – this feeling of peace was essential. With peace, instead of throwing hand grenades, you can dance to records.

“When the wall came down, all these derelict buildings on the border suddenly became locations for illegal parties. Before this, there was only Ufo club in Berlin. It was also the first time East Berliners could take drugs –- ecstasy emerged, and this feeling of unity was available for the first time.

"It didn’t matter where you were from, the colour of your skin, anything. The reunification of Germany happened on the dancefloor.”

Will McCartney is founder and editor of The Noise Narrative and a freelance writer, follow him on Twitter

Read this next: Get the best of Mixmag direct to your Facebook DMs