Features

Features

How Ukrainian clubs and collectives are aiding the war effort

Dancefloors are shuttered across the country, and clubbing communities have transformed into volunteer networks to assist the fight to defend Ukraine

At around 5:AM on February 24, 2022, the population of Ukraine woke to the sound of sirens. It could only mean one thing. Russia had invaded. Within minutes, worlds transformed. People who had been dentists, developers or shop managers hours earlier took up arms to defend their country. Martial law was imposed, forcing families to split up and men to stay behind. From Sloviansk to Odessa to Lviv, Ukrainians entered a new reality and left their old one behind.

Ukraine’s underground music communities are no exception. When Martial law was imposed, the country’s DJs, producers, sound engineers and promoters found themselves either volunteering to serve on the front-line or mobilising their communities to form volunteer networks, using their empty club spaces to support Ukraine’s defence. Now, most clubs and collectives in Ukraine have re-purposed into volunteer, logistical, military and supply networks, and are using their skills, knowledge, contacts and equipment in creative ways.

Collider Club

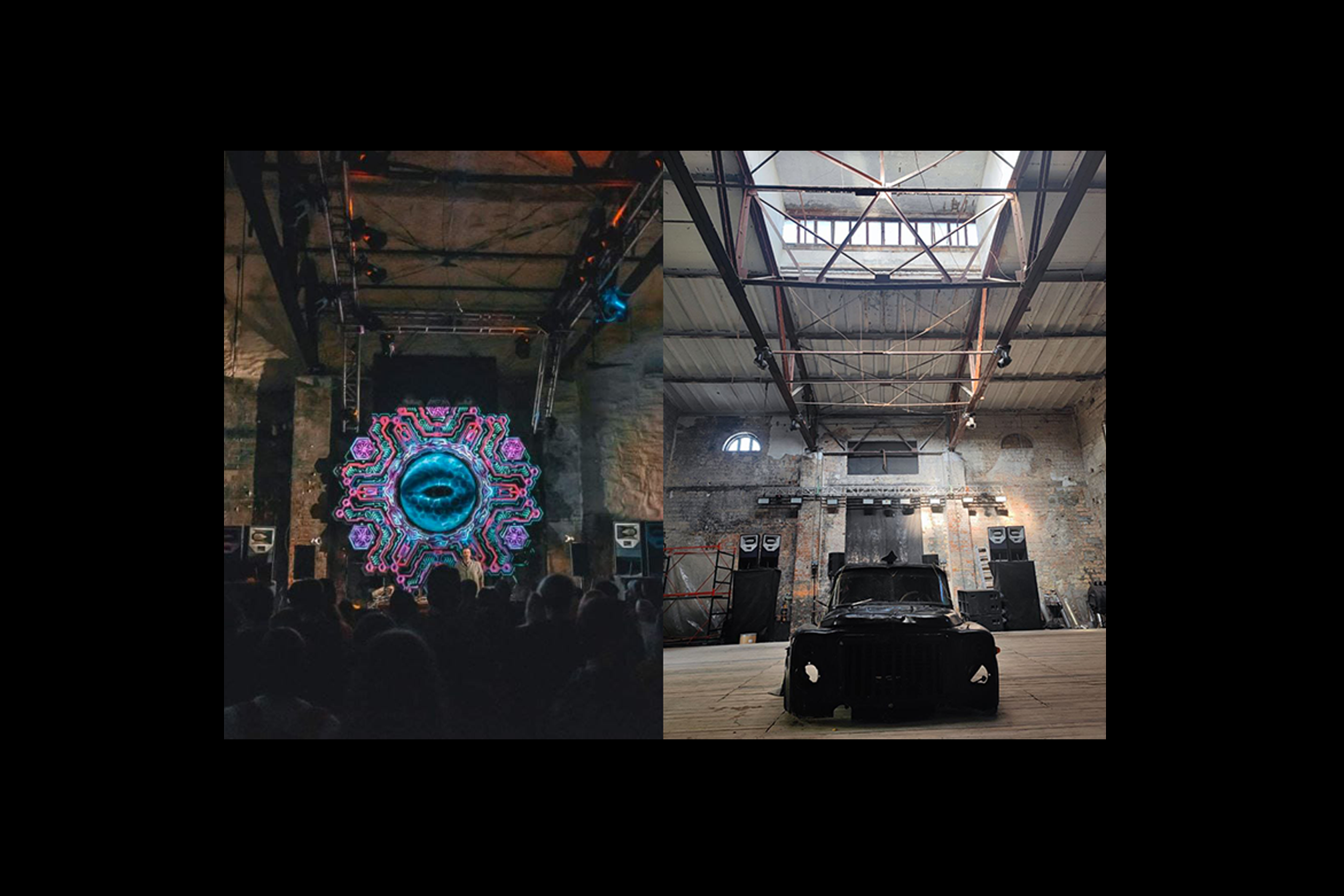

Collider Club, on the outskirts of Kyiv, is an event space designed to nurture and grow Ukraine’s underground art scene. The collective organises lectures and workshops for sound designers, DJs, producers and their extended community, with the aim of creating a cultural concept unique to Ukraine and its values. “Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ukrainians have felt like they’re second best or they aren’t good enough,” says Anatolli Borysenko, co-founder of Collider. “But we’ve helped the community realise their potential and build their confidence.”

Read this next: A list of ways you can support Ukraine

Anatolli’s wandering round the club as he chats, proudly showcasing the spacious outdoor area that overlooks the Rybalskyi Peninsula. Inside, the dancefloor’s packed with boxes of medical supplies. Before February 24, Collider invited experimental, house and techno artists to play in this room, but since the invasion they’ve had to repurpose. Now their Funktion-One soundsystem faces the doors, and when the team get intel that enemy forces are approaching, they play the sound of artillery fire at 106dB to deter them. The lights are rigged outside, and at night the spotlights and lasers shoot skywards to confuse drones or helicopters flying overhead.

Anatolli now lives in Collider along with three other members of the collective. They sleep in their office space and spend their days organising, delivering supplies and repairing cars to send to the frontline in the East. Anatolli says the invasion has transformed the Ukrainian mindset. It’s given them a sense of national pride and made them feel supported by the democratic world. “We’re fighting for the values of all of civilisation,” Anatolli says. “Not just Ukraine and Russia but the entire civilised world.”

Donate to Ukrainian Resistance

Module

They call Dnipro, a city in Ukraine’s East, the last fortress. “All the soldiers who go to the frontline come here to deploy and dispatch,” says Volodymyr Lozhko, who manages Module’s PR. “Refugees from the Donbas region and wounded soldiers come to Dnipro for first aid.”

As well as being a Ukrainian stronghold, Dnipro is also the birthplace of Module, a contemporary culture and music club and collective. “We’ve created something unique for our region and country,” says Evgen Gordeev, Module’s resident DJ. Although the world might see this war as a new development in Ukraine, Module sees it as a continuation of Russia’s invasion in 2014 which hit Dnipro particularly hard thanks to its close proximity to Crimea and the Donbas region. But this invasion acted as a catalyst for cultural revolution in the region. “After 2014 a lot of young people started to invest in local culture,” says Evgen Goncharov, co-owner. “With Module, we wanted to start something new and create a Ukrainian identity within music and art.”

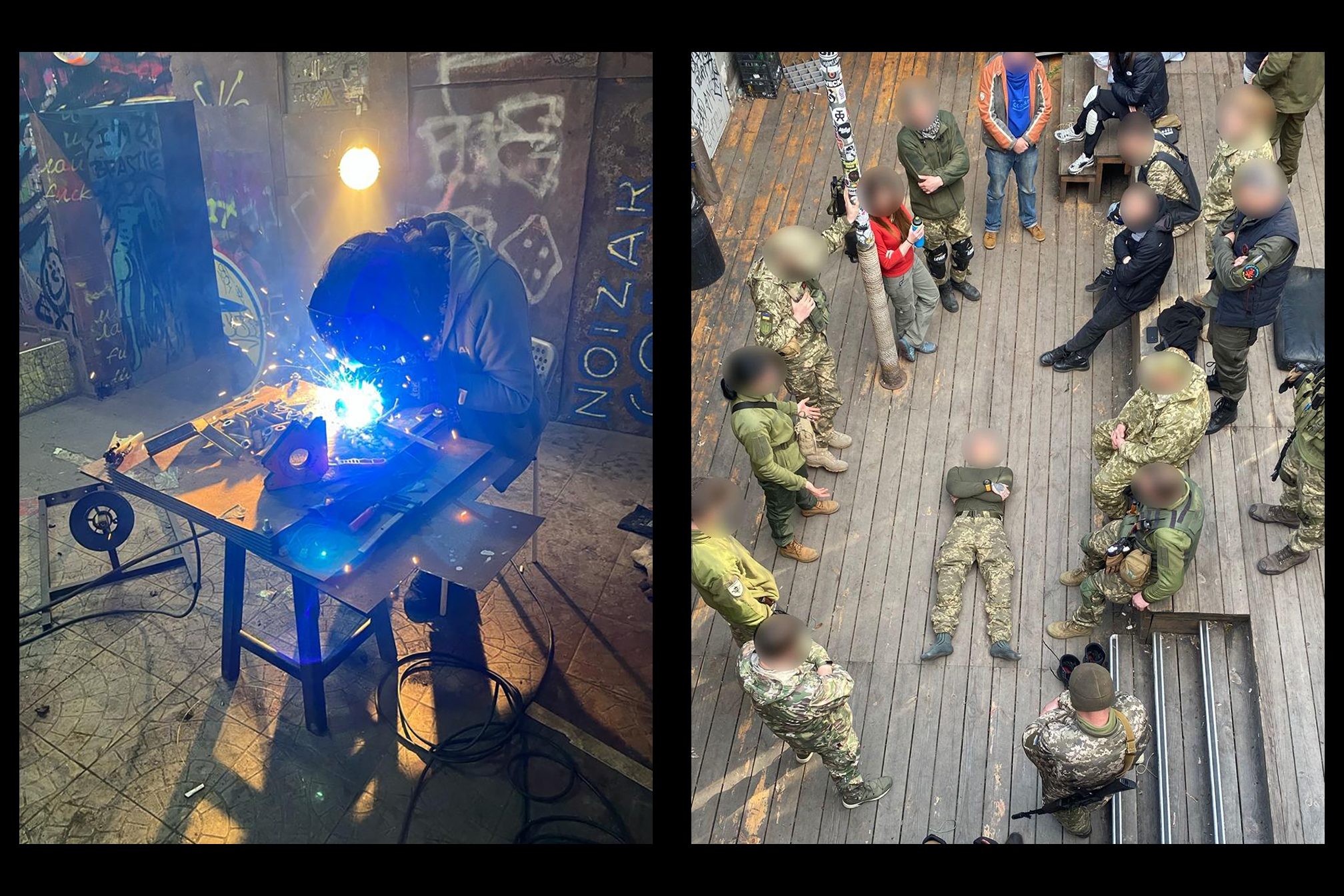

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February, Module quickly re-organised into a volunteer network. They locate and deliver cars to the frontline, source military equipment and store tactical medicine. The work is personal, seeing as a large proportion of the people who filled Module’s dancefloors now serve in the territorial defence. “It’s funny,” says Goncharov. “I was the manager of the club and now I manage logistics. Evgen was our resident and now he’s throwing fundraising events. We're still the same structure, we’re still Module, just with a different purpose.”

Module has an extended family of over 50 producers, promoters and DJs. Gordeev became a resident of Module after he fled the Donbas region in 2014, but he’s not the first artist the crew took under their wing. Kirilo Potras, one of their residents, lost a leg in the 2014 conflict, and Module raised money to buy him a prosthetic leg. Kirilo would be speaking today if he wasn’t volunteering on the frontline, delivering equipment to the country’s defenders.

Support Module

Detali

Before Detali formed in 2016, there wasn’t much going on in Ivano-Frankivsk. It’s a small city in the West of Ukraine, so when Detali launched its leftfield electronic music events in ever-changing locations, the concept rocked the city. “That’s why we have such a huge and supportive community,” says Detali resident Roman Kapiy. “Anyone who lives in the region has been to Detali at least twice, even if they aren’t into underground parties.” Today Roman and Oles Zazulin, Detali’s organizer and a DJ known as Zoolini, chat from their office, which transformed into volunteer headquarters the day Russia invaded. They describe their parties as tribal and unpretentious.

Read this next: How Cxema parties are changing the face of the Ukrainian electronic scene

Just like Module, Roman and Oles weren’t surprised when Russia invaded. “We grew up knowing Russia as an aggressor,” says Kapiy. “And it was just a matter of how they will express their aggression.” What has surprised them, however, is the cruelty and inhumanity displayed by Russian forces. Before the war, Detali weren’t political and focussed instead on nurturing underground culture. But now they spend their days supplying the Ukrainian army with tactical ammunition, humanitarian aid and mobilising procurement processes across Europe.

“Everyone we’re working with is part of the underground scene,” Kapiy says. “Which makes sense – the underground is a form of resistance. We’re resisting mass, commercialised culture. We’re still resisting now, but the object of what we’re standing for has changed.”

Kapiy and Zazulin stress that they aren’t buckling under negativity; on the contrary, they’re feeling positive and focussed. And when this is all over, and they can breathe again, they believe Ukraine’s club culture will be more vibrant and magnetic than ever before. “The parties will be crazy as fuck,” says Kapiy.

Support Detali

[Photos: Oleksandr Halushchak]

Dobrovoz

Vlad Fisun’s dedicated his career to accelerating Ukraine’s underground, and graced the pages of Mixmag twice in 2019 for impersonating Daft Punk on the streets of Kyiv and recording a live vinyl set in Chernobyl. But since Russia’s invasion in February, Vlad’s barely thought about music. Instead, he’s focused all his energy on volunteering for dobrovoz.org, an organisation which launched in 2014 after Russia invaded the Donbas region. Dobrovoz.org help civilian and military doctors transport medicine to Ukraine from Europe, and Vlad manages communications and logistics. The organisation was founded by Dmytro Yurinov who’s one of Ukraine’s pioneering promoters and has thrown parties since the early 2000s, inviting international artists like Cuban Brothers and Tummy Touch to make their Ukrainian debuts. Other volunteers include Maria Alferova, the former art director of Depstore party bar and a pillar of Kharkiv nightlife.

When Russian forces invaded Ukraine, Vlad gave his Kyiv apartment to refugees from the East and relocated to Lviv. Before the invasion, his days were spent gathering music, but now he spends his time organising and driving medical aid to and from Ukraine’s borders. Recently, he listened back to a mix he recorded three weeks before the war and was shocked by the melancholy, industrial tone of it. “It felt like a prediction,” he says.

Ukraine’s dance music community is dealing with personal tragedy on a mass scale. They’ve lost their livelihoods, their businesses and many are serving on the front-one along with their friends and families. The community will feel the impact of this trauma long after the invasion is over, and Vlad believes this will be reflected in the music that comes out of the country for years to come. But he’s proud of what the country has established in the last decade, and has positive hopes for the future. “Our music and club culture is still pretty young,” he says. “But what we’ve created has earned it’s place on the world stage.”

Donate to dobrovoz.org

Gnezdo Bar

Masha Naumova’s on her way to Kyiv to collect a dozen or so missiles. She chats from the passenger seat, at one point pausing to hand her ID to a soldier at a Ukrainian checkpoint. She doesn’t mind having to do this every 10 kilometres. “It makes me feel safe,” she says.

A few months ago Masha’s main occupation was running Gnezdo Bar, a speakeasy venue in Kyiv hidden so expertly tucked you’ll only find it if you know where to look. When the rockets started to rain down on her hometown, the thought of leaving didn’t even cross Masha’s mind. “I never considered it,” she says. “Lots of my friends are staying in Kyiv or fighting in eastern Ukraine with no hesitation. When an enemy comes to your motherland you have no choice but to defend.”

Read this next: “This is what you do when fascists come”: Kyiv producer John Object on fighting for Ukraine

Masha’s been an internal part of Ukrainian nightlife for decades. She used to be a partner at River Port, the team behind Collider, and since she opened Gnezdo the bar has helped shape the sound of Kyiv’s underground by nurturing local talent. The bar has around 10 permanent staff, who are all either serving in the military or working with volunteer organisations.

Masha is volunteering for a self-organised network called Zgraya which formed after the Russian invasion in 2014. “We focus on storing food, medicine, military equipment, and we’re relocating to Dnipro so we can react more quickly and provide food and water for cities that have no access to provisions,” Masha says. Two days before we speak, Masha helped deliver water to Mykolaiv, which had been without it for 20 days. The two founders of Zgraya also own bars, and Masha feels it’s no coincidence the nightlife community reorganised so quickly after Russia’s invasion. “Our businesses have closed so we can devote more time to it, and we can fundraise thanks to the friends we’ve made all over the world through music.”

Donate to Zgraya

Shum.rave

Shum.Rave are no strangers to the pages of Mixmag. Just over a year ago we shared how the Eastern Ukrainian crew gave hope to a generation by throwing parties in the shelled-out buildings left empty after Russia’s 2014 invasion of the Donbas region. So for this crew of young ravers, the events of February 24 were all too familiar.

Read this next: Raves not war: How Shum is building a new future for war-torn Eastern Ukraine

Shum.rave resident JmDasha dials in on her way back from Poland, where she DJed with Platform TU to raise awareness and money for the Ukrainian defence. Dasha grew up in the Donbas region, and until a month ago lived in Mariupol. The strategically-important city has been under relentless siege since the invasion began, and Dasha risked her life to escape without a humanitarian corridor. “There was about a 50/50 chance I’d survive,” she says. She left by car, and drove to a small Russian-occupied village. She spent two weeks figuring out a route to Ukraine, and then drove nine hours (it used to take 1.5 hours) to Ukrainian territory. She passed through 17 Russian check-points, and at each one she was at the mercy of the soldiers. When she finally made it to Ukrainian territory, she cried. She called her parents to tell them she was safe and then called Zhenia, the founder of Shum.rave, to tell him she’d brought her USBs. “It was a risk,” Dasha says. "If Russian soldiers knew I was a musician there would be a huge problem.”

Dasha says that in 2014 and now, Russia aimed to crush Ukrainian culture. The venues and bars that hosted Shum have been flattened, and Dasha’s apartment in Mariupol (pictured above) is now just a gaping hole. But despite it all, she’s smiling. She’s happy to be in Ukrainian territory and proud to do what she can to fight for her country.

Shum.Rave has released a compilation of music produced by artists from the Donbas region, ranging from noise to experimental to rap to techno. All proceeds will go towards Ukraine's defence – buy it here

Closer

Kyiv’s Closer has been instrumental in defining Ukraine’s underground since it opened in 2012, welcoming artists like Moodymann, Helena Hauff and Ricardo Villalobos onto its smokey, strobe-lit dancefloor and providing a space for countless local artists to cut their teeth. Ex-soviet countries tend to suffer with identity crises living under Russia’s threatening shadow, but Closer created a vibrant and unique cultural revolution that doubled up as a giant middle finger to Soviet control.

Read this next: How Strichka turns Closer into a party of endless discovery

Today Sergey Vel chats from Closer’s garden. The space is empty except for a disco ball hanging above some well-worn decks, but it’s easy to imagine the place packed out with bright dancers, cigarette smoke clinging to the air. Now, Closer is using it’s state-of-the-art kitchen to provide up to 300 meals a day to the Female Pokrov Monastery, Institute of Pediatrics, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ohmatdet Children's Hospital and Ukraine’s Territorial Defence Forces. In Closer’s nearby hotel, volunteers make Molotov cocktails, camouflage nets and road blocks.

Although the club is closed, business has come to a halt and their community is serving on the frontline, the pervading mood is one of positivity. “We’re happy because we understand what we need to do,” Sergey says. "The Ukrainian people have come together, and we know what’s important.”

Sergey ends on an anecdote. “My friend found a brand new car on the street with a full tank of gas and keys in the ignition. He waited for a couple hours to see if anyone came to get the car and when no one did, he drove him and his family to safety. Then he looked in the glove box and found a registration and phone number. He called the number, and a man picked up and said ‘You have my car? Good. I have five. I thought someone might need it. So take it, and when this is over you can bring it back.” Sergey smiles. “It’s difficult and sad, of course. But there are some beautiful moments, too.”

Support Closer

Alice Austin is a freelance writer and regular contributor to Mixmag, follow her on Twitter