Features

Features

The gentrification of jungle

Kwame Safo talks to Marc Mac, Bryan Gee, DJ Flight and Junior Tomlin about the futuristic Black art form and why its Black roots should never be forgotten

The UK has always been fortunate to be at the cutting-edge of underground dance music, which is often created by grassroots, working class Black communities. But somewhere along the way large aspects of the Black experience have been erased due to an unwillingness by the music industry to accept the artform in its unapologetic and uncompromising form.

The gentrification of jungle is the systemic erasure of the Black aspects of the genre which runs alongside a patriarchal ecosystem that renders the contribution of women, and especially Black women, invisible. The result? A sound which is wholly compromised historically and replaced with a new, rewritten narrative which bypasses the roots jungle.

Jungle Techno was the original moniker for the genre born from the music of Black individuals from Chicago and Detroit. The revolutionary music of acts like Adonis, Mr Fingers, Underground Resistance and Kevin Saunderson would form the basis for subsequent revolutionary sounds from Black communities in the United Kingdom in the early 90s. There was and always will be contributors of other races especially in the jungle and drum ‘n’ bass fraternities. But it could be argued quite convincingly that the trajectory and longevity of white artists in drum ‘n’ bass has been much more fluid, mainly in part due to the visibility and opportunities afforded to them, even when those white artists enter the musical landscape after Black pioneers.

Jungle as a sound still exists today. The original proponents still fight and preserve its legacy via labels like Reinforced run by Marc Mac and stations such as Kool FM (now known as Kool London). The drum ‘n’ bass derivative has been a lot more popular though. Popular being defined by its spread in the market space and the frequency of events labelled as “drum ‘n’ bass” compared to the weight of jungle events which typically marked its strongest years between 1993-1995. The successes of drum ‘n’ bass were also not distributed as evenly to the era of jungle and meant Black contributors did not benefit in the transition, as they were left behind in the “rebrand”.

Black women have rarely found a “safe space” in the music industry to not only articulate themselves unapologetically but to also be appreciated and recognised for their endeavours. The intersection of racism and misogyny, coined by queer Black feminist Moya Bailey as misogynoir is an everpresent attribute of the gentrification of most Black music scenes. As DJ Flight tells us: “I'm constantly feeling like I'm trying to justify my existence. What do I need to do to get recognition? It almost feels like I’m being erased in real time”.

Lessons and the education of future makers of jungle in regards to the genre’s context is important in order to improve on past mistakes that the industry has made in failing to create and uphold spaces for Black innovators to communicate art. The future of jungle, and all Black music, should include Blackness from its roots all the way to its packaging for a wider, global audience.

We spoke to Marc Mac, Bryan Gee, DJ Flight and Junior Tomlin for their insights on the roots of jungle, the socio-political environment in which it was born, it’s progression into drum ‘n’ bass, the industry around it and why it is and always will be Black music.

Marc Mac is synonymous to jungle and drum ‘n’ bass thanks to his work with Dego as 4Hero and their record label Reinforced. A soundsystem and pirate radio veteran, his induction into raving was following soundsystems like GQ, Touch Of Class, Just Good Friends and Mistri all over London to hear a “melting pot” of Black music that would include reggae, soul, boogie and disco, a mix that would later influence his production palette and jungle music on the whole

Being a DJ, broadcaster, producer, promoter and label boss who has been active in soundsystem music since before the acid house explosion gives Marc Mac a unique perspective on the Black origin and evolution of jungle. He would battle police to run events and face what was arguably the beginning of the most punitive filter on Black promoted events, the 696 form, and as a rising artist would try to be as “faceless” as possible to circumvent the racial bias within the music industry and wider society. Albums like 4Hero’s ‘Parallel Universe’ were interwoven with subliminals and ran counter to the simplified hedonistic perspective of the rest of the rave scene, pushing an afrofuturist narrative based on the plight of Black people in the UK and inspired by the scientific progressiveness found in the Black music coming from contemporaries turned friends such as Kevin Saunderson and Underground Resistance in Detroit

Being a Black kid growing up in the 70s and 80s, your first introduction is going to be the soundsystem, because that was the Windrush generation, that was their thing, they brought that from the West Indies, they brought that soundsystem culture and that music with them. The big speaker boxes and so on.

The importance of the soundsystem is that it comes from the Windrush generation, from the West Indies, and we learned that culture and carried it on and it’s in jungle and drum ‘n’ bass today in the form how people produce music that is soundsystem ready – the timeline comes right from Windrush to now, it’s important to make that connection and keep the dialect and why we can’t call it anything other than Black music.

Our local youth centre was home to a soundsystem called Emotions which was the soundsystem I grew up with, sneaking in the back door because I was a kid, getting a glimpse of them setting up and testing out the soundsystem. I later on found out it was run by MC Moose, and I’d always known him as the reggae soundsystem man but later on he became one of the most prominent MCs out there in Jungle music.

The great thing about reggae soundsystems is that they were very eclectic without even realising it; many times you would go to a reggae dancehall and the line would be “too much of one ting is not good” then they'd switch it up! All of a sudden you'd hear a soul record get played! You heard soul music, you heard the rare groove. So, all those elements of underground Black music, when we started to produce music, they were already in our psyche and those were things that we brought through when we were making music. The other thing that was part of the melting pot was also being a Black kid in London, with Black friends, and listening to music which at the time was kind of seen as ‘white music’. Mainly Punk and two-tone, which at the time was the music which was trying to bring the Black and the white thing together, so that was the first early kind of music that was mixing two different cultures.

The final part in the cooking pot of music would be the house music, but again the first time I heard house music with acid lines was in reggae parties. If I went to a music shop in North West London, Harlesden was my spot where I was going for records and the record shops. We had Jetstar Distribution around there, which went on to become quite big in the jungle around there. We had Lightning Records, you’d be buying records for the soundsystem, looking at the latest 12” records, mainly a lot of the US Soul that was coming in. But then they would say “we got this different kinda ting you need to check this out!” and it was a record label called Trax records so you’d hear things like Adonis ‘We're Rockin Down the House’ and Chip E, Chicago house stuff and things like that, they were coming through the reggae shops because they were importing them and selling the records, mixed in with all the soul music, the reggae music you’d have the house music.

From ‘91 the word jungle was known, in certain circles and in certain clubs that you went to, certain DJs would play jungle and the labels like Shut Up N Dance, Ibiza Records, Noise Factory, Limited Edition. Jungle music at that time didn’t have to have a reggae MCs vocal on it. It was about how the breaks were put together. And mainly the bassline. The sub bass was important, as it is in any Black music culture. It was called jungle even though it didn’t have what the ‘94 jungle brought in, which was the dancehall influence. But the word jungle techno was around since ‘91. In that point in time you’d hear 4/4, breaks layered and chopped, and a deep reggae bass. That was enough to call in jungle techno. Even though it didn’t have dancehall samples on it, you’d hear an MC chatting over it on a soundsystem.

It was very multicultural, it was born out of the traveller raves. Growing up in Wembley, when people like Spiral Tribe, who went round the country doing illegal raves, and when they came to London they’d come to Wembley and they had a white following but the neighbourhood was Black. Then there was the technicolour rave in Wembley in ‘98 and ‘99. A lot of the Black people from that neighbourhood would join in. Prior to that the raves were segregated; if you went to a soundsystem it would be Black people. But when rave exploded, that’s when you had the mixture of people.

Everyone was fine calling jungle Black music – because every element that came into it, be it jazz or funk breaks, the reggae and the house and the gospel, everything was mixing and sampling and grabbing from Black music. At that point in time we didn’t live to think of it being any different. There was a magazine called Black Echoes because it talked about Black music. That changed as things started to evolve and institutions [got involved]. But at the time there was no question about it. It’s important to hold on and understand the history of the music so come 2020 we’re not trying to guess why it’s Black music or why you think it isn’t Black music. If you understand the history of jungle then you’ll be aware that it’s Black music because it grew from all these forms of Black music.

There was a point when there was intelligent drum ‘n’ bass and jungle. If you had a reggae vocal in something, it was jungle. But all of a sudden if you took that you, it became intelligent. At the time I thought that was quite weird, even though we were quite involved in making intelligent music at Reinforced. We used that word because it was about how we were evolving our use of technology and new equipment, not because we were splitting away from jungle. But scene policy makers jumped on that to make the split.

I do think it's got to do with a lot of the outside institutional pressures, from policing, from government and putting pressure on the clubs because they could see jungle being a very Black entity, so then you're going to get this backlash. So I think those people making the policies were putting pressure on the clubs at the time, and the promoters could see that “ok if we call this a different night and we eliminate the jungle side of it, which is becoming very associated with the Black side of it, then we can get through and not have the hassle from the police and get out late licences and so on”. It’s almost like the hand was forced a bit to eliminate the Black side of it.

From the early days of raving I got turned away from doors. And this is not just in jungle. I was turned away from the Fridge when Soul II Soul was there. They were trying to keep the Black numbers down; the security would walk down the line and pick us out and say, “you’re not raving tonight”. Then there was the dress sense, they’d have an excuse maybe if you had a baseball cap or trainers on. You could see the pressure was on to have less Black people on in clubs. We weren’t trouble makers. It wasn’t happening too much in the jungle scene but you could see the pressure on promoters to iron us out.

The police were always looking at flyers. We had a party called the Dope Jam – they didn’t like the name – they confiscated my equipment and only because I had a good friend, a white guy, he understood the situation and the politics and he said, I’m going to put a suit on and go and get the equipment back, and he did. We had to change the name and then the party could go on.

In America a Black parent will have a talk with their child about policing. In the UK we have a different talk about education and schooling and “you have to try 10 times harder than your white friends”. We took that as natural and normal and I took that through life. Whatever I’m doing I’m going to have to try harder else I’ll fall through the cracks. Because we’re living in a country where – people don’t like to say it – there is institutional racism. When we signed to a major label, when you’re going global, it’s going to be harder for us, with our faces on the cover of magazines. We always wanted to be faceless because we had that knowledge. All the early records on Reinforced were faceless; people didn’t know we were Black until we turned up at the rave. We’re driving through parts of England and people are maybe seeing Black people for the first time. We were always aware that showing our face might be problematic. That’s how it was – it’s not like we’ve gone past it, we’re having similar problems but in a different way.

Going to Detroit, I understood how Black techno was. And I’ve never seen techno in that way again. Meeting all those guys: Underground Resistance, Claude Young, Kevin Saunderson. You’re with Kevin Saunderson and there’s few promoters where you’re going to meet the promoter and go to their mum’s house. I was sat in Kevin Saunderson’s house watching TV. And then you’re going to the studio, and to Underground Resistance’s studio, and to see Claude Young at the radio station. Joining all these dots and how they engineered and had a Black underground music. It was 99 per cent Black people and it spurred us on and made it feel like we were doing something right and that it had a future. We saw a parallel between Reinforced and Detroit and we made some good friends. Mad Mike and Underground Resistance would stay on our studio floor because we’d stay up all night talking about politics. We had a similar kind of battle: people seeing techno as white music and us seeing a mirror in that in terms of what was happening with rave music.

When we sample rare groove records I know why I’m doing it, because I was at those parties where DJs played rare groove. When I hear that sample I’m remembering the MC on it, the environment, no lights, shoulder to shoulder in the blues dance, the smell of all kinds of things in the air, I remember that. It brings back all those memories of being in a blues dance in a Black neighbourhood surrounded by Blackness. A kid that comes up today will sample rare groove and put it in his jungle without understanding anything about that. The music is inclusive but people shouldn’t forget and if a member of that community asks them to understand, they should. Instead of turning around and saying “it’s not Black music”. It’s about understanding the history, that sometimes you might be sampling a Black gospel group or a heavy Black jazz record.

People don’t understand that 4Hero for me and Dego was about escapism, its afrofuturistic and its escapism. If you go through the 4Hero record from ‘Parallel Universe’; ‘Parallel Universe’ was about being on a universe which was the same as the universe, but without the problems of racism. As Black people you’re in a place where you’re not wanted and you go into your mind and create a space where you are wanted.

V Records boss Bryan Gee grew up listening to reggae soundsystems and was perfectly placed to embrace the acid house explosion in London at the end of the 80s. He witnessed acid’s morph into what would later be known as jungle, as a new wave of Black electronic music from the States landed in the UK for the first time and blew people’s minds. Bryan was among a group of DJs including Jumpin Jack Frost, Fabio and Grooverider to champion it via pirate radio and parties, much to the chagrin of their Black peers and community in those early days, who were more used to hearing them play funk, soul, reggae and rare groove and apprehensive about this new form of Black music. There was also a scepticism about the rave movement thanks to highly publicised stories of drug taking in the tabloid press

They persevered however, with Bryan plugging into the deep frequency between the Black artists making house and techno in Chicago and Detroit, the Black DJs who were buying the records in the UK and what he felt was a sonic imagining of Africa, as if instruments like the Talking Drum of West Africa had been rendered electronic

For us as Black people in Brixton to be playing acid music was like a sin. The boss of Passion FM, the pirate me and Jumpin Jack Frost used to play on, would say “What the bloodclart type of music is this?!” People would look at us like we were mad or possessed. If you’d never been to these parties you would think that. Sometimes music has to be experienced in that environment to understand it.

I had dreadlocks and my name on radio was Funky Dread and we were playing this crazy, mad music and people shunned us. We had to fight against that backlash in Brixton, being on a Black radio station, but we continued because for me I never heard the ‘crazy washing machine vibe’ of dance music, I heard the tribal element of it. The early techno was made by Black producers in America. Some of it was made by crazy white people in Europe and you could hear the difference between the music. But not all the time because some of those white boys would produce tunes where you were like, “woah this has got some rhythm, some groove to it” but most of them white boys from Europe would be making washing machine music which was fine but I didn’t gravitate toward it. There was some stuff with tribal vibes to it which we would now identify as a jungle vibe, but that word wasn’t around at that time. There were tunes like ‘Africa’ and ‘The Motherland’ and you had Marshall Jefferson and Mr Fingers – it had that vibe to it.

There was this guy called Danny Jungle. He was a very loud character, everybody knew him, he was always expressing himself. If a tune was good, he’d be shouting. There was a theory that if Fabio and Grooverider played a tune and it had that tribal African reggae feeling about it, and all of the Black people would feel that, that’s where we were coming from, when we heard these vibes in the hardcore it would make us feel better, “that’s a proper b-line!” I don’t know if Danny would say “jungle!” or if he’d just blow his horn when a tune had those elements, but there is a theory that the word jungle came from Danny. He would always blow his horn when a tune had that ghetto b-line! We didn’t know what it was called but it was urban, it was tribal, it was Black. And jungle just sounded like, “yeah!” Cos 99 per cent of us had never been to the jungle but we’d seen it on TV. For me, the sound of the jungle is the African drums and the birds and the atmospheric vibe about it. That’s how we interpret jungle – it’s something from Africa.

There was a label called Warriors Dance, in the ‘88, and it was run by this rasta called Tony Addis and he had a studio set up over West London. And the music was strictly African influences, fusing the techno and the acid with the African tribal beats. That was what we were hearing dem times there. That was jungle. If you do your homework, check it out. It made us feel like we were on the right path.

When I went to jungle raves it was predominantly Black faces. Someone brought in the term drum ‘n’ bass and it took the power away from Black people, because when it was called jungle it was our thing, we had the power. Somehow we lost it. A lot of people got into jungle because of the Blackness. When the music started taking on reggae influences: Buju Banton, Shabba Ranks, Dennis Brown. I could talk to my family, they wanted guestlist, they wanted CDs, they could understand it when it was jungle. They all knew the originals to be reggae music. Dem times there were very Black. So the minute it changes, a lot of Black people would say “I don’t understand it” because the reggae was gone.

Drum ‘n’ bass was massive in Brazil. Reason why? A lot of early drum ‘n’ bass was sampling samba music. When we went to Brazil you’d hear all of these Brazilian songs over drum ‘n’ bass. It was massive. The minute the Brazilian artists took out the sample because they realised it appealed in Brazil but in Europe people were moving away from that sound, and they wanted to make music like European artists, like us, they stopped using the samples and it wasn’t big in Brazil anymore because the people couldn’t relate to it. It was the same over here: once you took out the Buju Banton and the Dennis Brown and the rare groove then people are gonna be like, “I’m going to listen to EZ and Stormin” because UKG carried on and picked up the urban, dubby, reggae flavour so everyone who left jungle went to garage. When I go to a garage dance I see all the old junglists because that’s their vibe, they want to carry on that Blackness. Drum ‘n’ bass took over and got more musical and started to experiment with European sounds and different countries brought their influence to it and your average junglist can’t relate to it. It’s too noisy!

The biggest influence on DJ Flight’s long career in drum ‘n’ bass was seeing Kemistry and Storm as a teenager. The pair blew her mind and, alongside DJ Rap, became a major inspiration for her as a young, aspiring selector. She would go on to hold down residencies at major London clubs, host on BBC 1xtra, start her own label and be welcomed into the Metalheadz DJ team, of which she’s been part for 21 years now

The DJs who inspired Flight were some of the only women to be featured prominently on line-ups in the mid 90s and, as Flight details below, not too much has changed in 2020. There still aren’t as many women DJs in drum ‘n’ bass as there should be, let alone Black women, and Flight continues to spin incredible DJ sets, whilst fighting for equality in the scene via her EQ50 platform and mentoring programme

I followed the path of seeing big dance tracks on Top Of The Pops and getting into radio, I used to listen to a DJ called Steve Jackson on Tuesday nights on Kiss FM. This was the early 90s so he was playing early hardcore and breakbeats. The House That Jack Built was the name of the show and it was really just rave music, he was a Black DJ as well [In 1999 Jackson would take Kiss FM to court over unfair dismissal based on race when he was suddenly sacked from his popular morning show Morning Glory].

When I was first going out it was really mixed, and that's what fully made me fall in love with the music, I felt completely comfortable, completely at ease. There were Black kids, Asian kids, white kids, mixed kids… All different kids and when I graduated to the proper raves, again it was a whole mixture of people. At some of the more ragga-style jungle dances, or dances where it was slightly darker in sound, it would be Black people.

This party Innovation was doing a London club tour in 1995 and one of the events was at SW1 in Victoria and it was packed and DJ Rap was playing and it was really good and then I just saw these women appear behind the booth who looked quite funky and I just thought, oh they must be her mates, but then they took their jackets off and got their records and dubplates ready and I was like, wow! And they came up to the decks and it was Kemistry and Storm. I saw Kemi – bleached locks, light skinned, looked stunning – I was just like, wow! They played and just blew my head off. What they played was different to everybody else too, it was deeper, it was darker. I don’t want to use the word menacing; it was just different to what I’d been seeing regularly. I was stood by the decks, staring intently, watching their hands and stuff, and my mate Brian leant over and said “press that button” and I didn’t know what he meant but he wanted me to rewind the tune and he just leant over and pressed stop and I remember Storm just looking over at me just standing there! They blew me away, it was the first time I saw them and I became their number one fan.

I think it's quite hard to get people to understand [The lack of support for women in d’n’b] because for them to hear it coming from me, they see what I've done: I had a show on the BBC, and I ran a label and I've been a Metalheadz DJ for 21 years now and I've been to so many different countries around the world, that people probably think that I’m probably exaggerating a little bit. I think they probably don't get it because they look at me or they look at someone like Jenna G, who’s had masses of success as well but who’s also had the piss taken out of her, she hasn't been paid properly by some big artists, like some well known artists and labels and she's been seen as difficult because she stands up for herself and she doesn't take shit from people. Chickaboo is another one. She was the first woman jungle MC. She's been going since 92. She's from Birmingham originally, but has been living in London for nearly half of her life now. She had a partnership with DJ called GE Real but he sadly passed away. She doesn't get the props she deserves, and she's had shit loads of stuff. She’s had songs in the charts with Timo Maas, she was part of the Soul II Soul band for a decade, she’s worked on breaks, house, d’n’b, jungle and all kinds of stuff and it’s only really now that I’ve forced her to come back to it with the EQ50 stuff people are like ‘fucking hell, oh yeah, Chickaboo she’s great.’

As for Black female DJs in drum ‘n’ bass? There have been so few who have made it to a particular level. I’ve known of quite a few who have done pirate radio or mixes but didn’t take it that far because they had kids or weren’t getting the support that they needed or wanted. But in terms of ‘making it’, hardly any.

Someone tweeted a thread and they were talking about the infantilisation of Black women and it just clicked and I thought “fucking hell that's exactly what I've been through” so it's where no matter what you do or how far you progress, or what you achieve, or how amazing you are, it's never going to be enough. Because I’ve been around for so long and people knew my face before I was even DJing – I’ve known a lot of these people since I was 17 from going to Blue Note or to record shops with my mates. A lot of see them still see me as little Nat who’d poke her head over the booth to see what they were doing. Even though some of those people did book me – I had residencies at Fabio’s night Swerve, Grooverider’s Grace and Prototype at fabric – I was always the warm-up DJ and it went against me quite a lot because if I had two bookings on one night, neither would give me a later slot so I had to pick one and I know if I was a man it wouldn’t have run like that. It happened at 1xtra too; I had to give up two of my residencies at fabric with Adam F and Grooverider but when I joined 1xtra my show was live on a Friday night and the executive producer was like, “Do you want to join the station or do those gigs” and it did wonders for me but I did wonder why I always had to choose. I’m proud of everything I’ve achieved but I know that if I was a man or a white woman it would be way more. The number of bookings, the regularity, even what I’m paid, would have been higher.

From a UK perspective there hasn’t been near enough Black women DJs [in jungle and drum ‘n’ bass]. All these guys are happy to have Black women looking after their stuff like a family member – a mum or a cousin or a sister – looking after their every day shit but none have been pushed to the forefront. Unless they’re a singer but singers have the piss taken out of them as well. Diane Charlemagne [who sang on Goldie’s ‘Inner City Life’], it’s a tragedy she wasn’t bigger than she was.

Labels are far too precious about protecting themselves and their output and their sales and when they do parties they make sure they only have their artists on the line-up and they don’t really deviate too much. Generally everything’s become a lot more selfish so there are people who should be known and should still be playing out but they’re not, they’re just not remembered.

When something [from Black culture] becomes popular in the UK, Black people are a minority. So there’s only so far you can get trying to stay within your community – or other Black and brown communities (I don’t like using minority as a descriptor). So if you do want to branch out and become bigger, expand your reach, that’s obviously gonna be a lot of white people, so what you look like, what you sound like, even how you dress, will determine how far you get which I don’t think a lot of people would admit to.

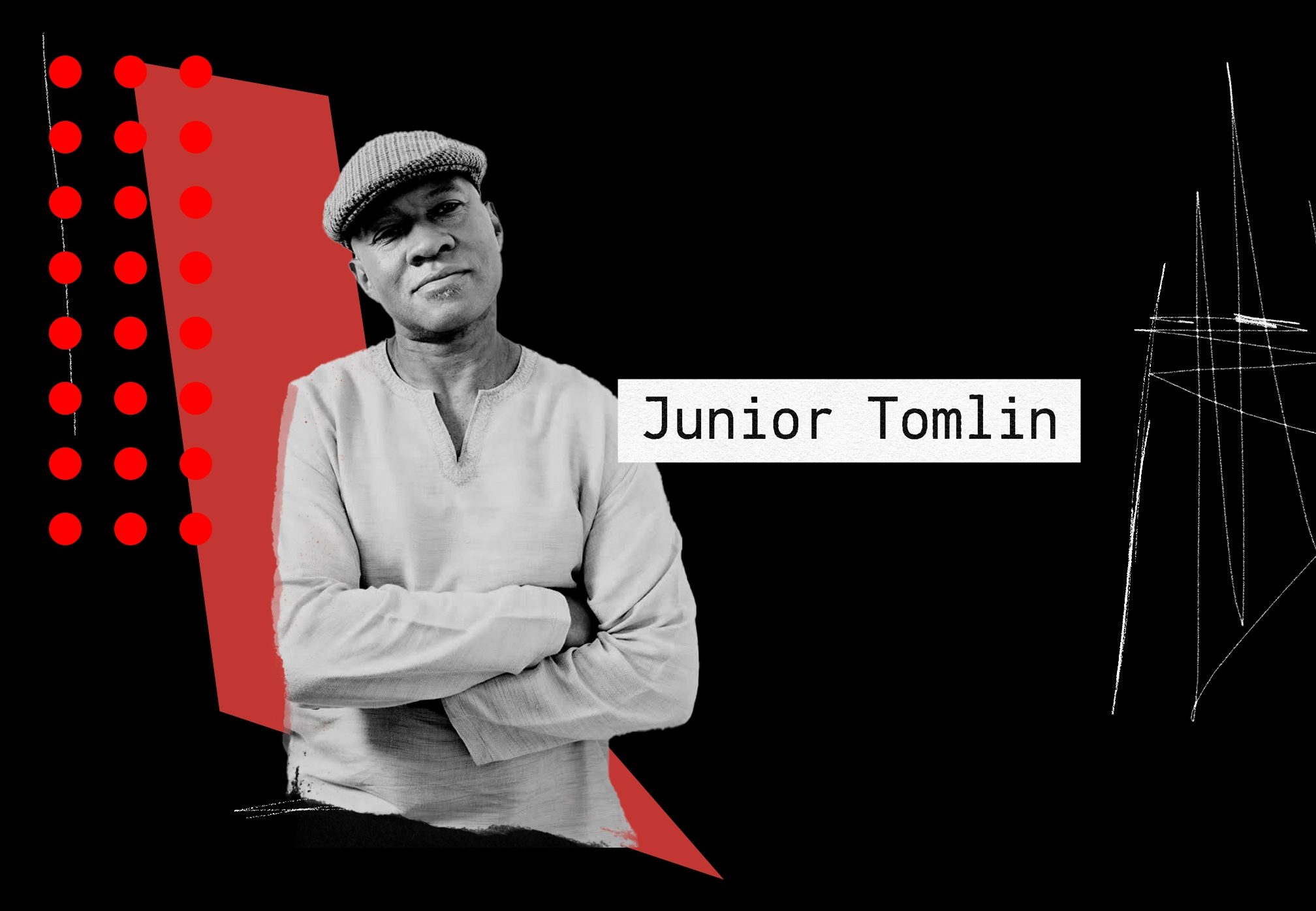

Junior Tomlin was one of the only Black artists creating flyers for raves during the acid house, hardcore and jungle eras. His work is the injection of unapologetic Blackness into the rave environment and it explores science fiction, surrealism, community and utopia in a groundbreaking way. Dubbed ‘the Salvador Dali of rave art’, to say Junior Tomlin’s futuristic perspective was ahead of the curve is a complete understatement (unless the curve was a nod to his love of science fiction and the curvature of the hull of the Starship Enterprise). It was a vision of the future to accompany the futuristic music being played at raves in the late 80s and early 90s and Tomlin forged a distinct afrofuturist aesthetic years before the term was officially coined in 1993. A new book on Velocity Press celebrates his 30-year career

When I worked with [legendary London promoter, venue owner and founder of Deja Vu FM] Sting he was one of only 2 Black promoters who I actually worked with, so the work for them is more Afrocentric, so to speak. Because Sting, he ran two clubs, Telepathy and Life Utopia. Life Utopia had a big crowd of white Europeans, so [my art for that party] serviced that end of the market. Still surreal, still semi sci-fi but it served that purpose for that end of the market. And when it cames to [seminal hardcore and jungle rave Telepathy], part of what I wanted to produce was my own Blackness. [Because] I wasn't doing a lot of Black characters or black art.

I enjoy science fiction so a lot of my work contains a sci-fi element, then over time I merged the sci-fi with the fantasy, with the surrealism, with afrofuturism and put it all down into one package. It's always to do with forward thinking, a possible future that we could have. I was the only person projecting that type of imagery.

It’s an idea, a dream, a vision about where Black people could have been at this moment in history. We could have been running our own space programmes. We are conquerors of anything we do, we are inventors, we are creators, we are educators. If you listen to jungle, drum ‘n’ bass, hardstep, dubstep, you listen to that music and you can think of the future. It is not of the present. Not only that it also encapsulates a whole lot of snippets from sci-fi films and TV shows. You might hear the swooshing doors of Star Trek, something from the Alien movies – themes of menace, foreboding, it’s all there interwoven in the music. If it’s from a sci-fi film then what does it tell you about the music, because the artists are thinking of the future when they make it.

Black Panther is the epitome of afrofuturism. Look at the styling, they're in a futuristic city that stands alone against everybody. That’s pure afrofuturism in one film. It’s Black people in the future. We need to get to the point where we own our own tech, design our own tech, make our own tech. If you own and create your devices you basically rule the world.

Kwame Safo is a DJ, broadcaster, label head, producer and music consultant. He is the Editor of Mixmag's Blackout Week and you can follow him on Twitter here