Features

Features

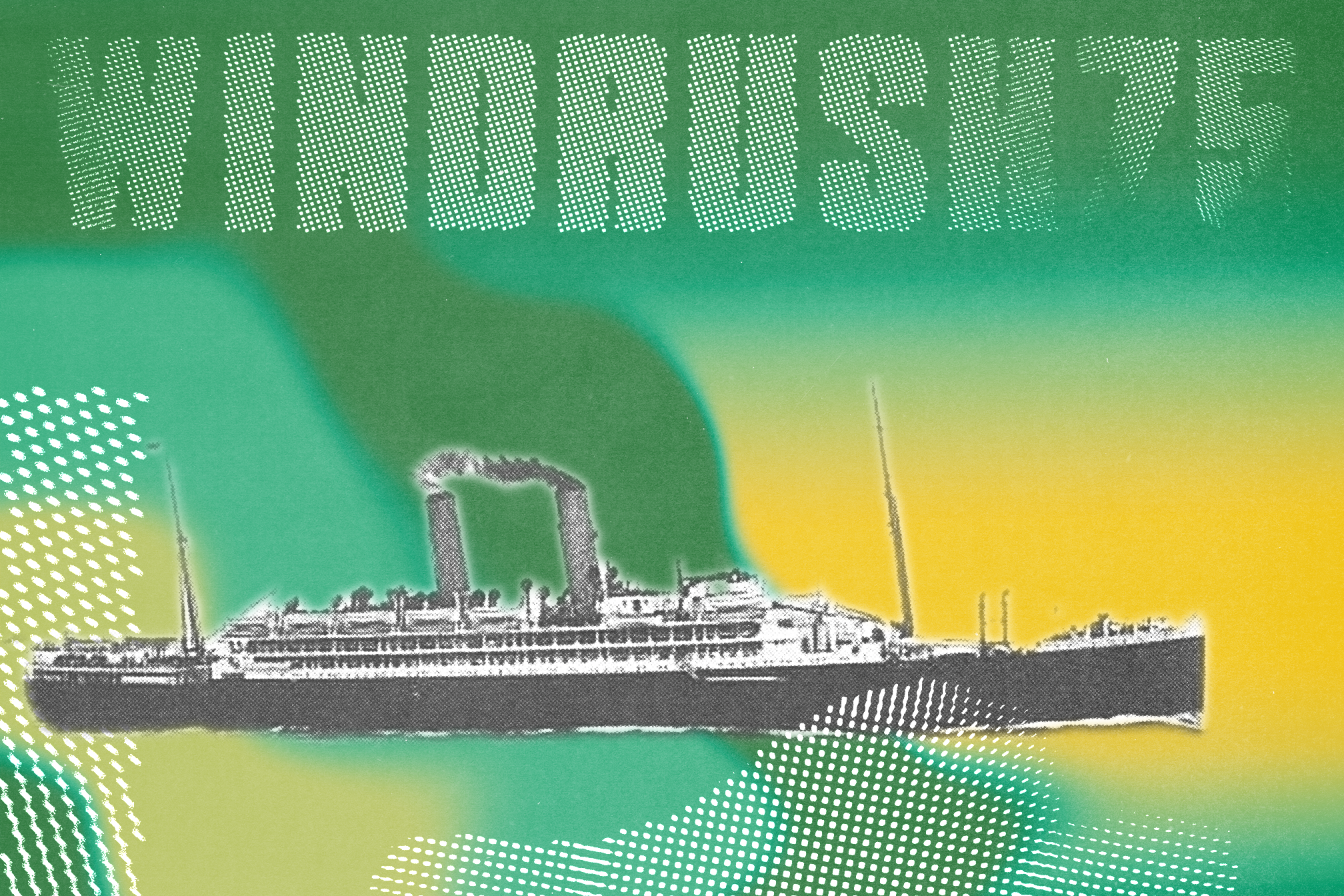

The forgotten ships of the Windrush Generation

Poet and academic Hannah Lowe explains why Windrush is the ship that defined a generation and reflects on the diversity within the migratory period

Mixmag is running an editorial series to mark the 75th anniversary of Windrush, find out more here

Fifteen years ago I placed an advertisement in the Liverpool Echo asking for anyone who remembered the arrival of the SS Ormonde to Albert Docks, Liverpool, in 1947. This was the ship my father had arrived on from Jamaica. I’d found its name many years after dad’s death in a notebook he’d kept about his early years growing up in Jamaica. Like many others, he had travelled to America during the Second World War to work as a farm labourer, and on his return found few opportunities in Jamaica. This is the ‘predicament’ to which he refers in the notebook’s final paragraph:

My thoughts turned to immigration as a way out of my predicament. I had been hearing from people that it was easy to get to England, so I started to make inquiries as to how I could get there. I soon found out that you could book a passage on ships bringing back servicemen who had fought in the Second World War. So I duly booked my passage on the SS Ormonde paying the princely sum of £28 to get to England.

I didn’t hear from anyone who had seen my advertisement but I kept looking, eventually finding the Ormonde’s passenger list at the National Archives, which lists my dad’s name and the names of two boxers I knew he had befriended and travelled to London with.

Read this next: On Sundays, Glorious Sundays, the culture of the Windrush generation came to the fore

Ormonde arrived a year before the Empire Windrush, which is commonly cited as the first ship to carry Caribbean migrants to Britain. In fact, there were two ships in the post-war period that sailed before – the Ormonde which carried 108 passengers and the Almanzora, which carried around 200 and arrived to Southampton in December 1947. On board the Almanzora was the poet James Berry who went on to chronicle the experiences of his generation.

Stirred by restlessness, pushed by history I found myself in the centre of Empire – James Berry, ‘Beginning in a City, 1948’

Why Windrush?

Why is Windrush known as the first ship to arrive, so entrenched in the national imagination?

The answer lies in the unique set of circumstances around its arrival, which in fact make its journey atypical. Windrush carried far more passengers than the ships that came immediately before or after – 492 people arrived to Tilbury, Essex, from the Caribbean on June 22, 1948. The reason for this surge in numbers was the recent passing of the 1948 British Nationality Act, which conferred the status of citizen on those living in the colonies.

But the British government were not expecting so many people to be motivated to travel because of this change and were alarmed when they realised how many migrants were aboard. They sent officials from the Colonial Office and Ministry of Labour to meet the Windrush, including Ivor Cummings, who was the son of an English mother and Sierra Leonian father.

Read this next: How Trojan Records founder Lee Gopthal created a musical legacy of love, hope and unity

There were also journalists and photographers and the ship’s arrival made the newspapers. Among the journalists present was Peter Fryer who went on to write Staying Power, a foundational book about Black British history.

Pathé filmed a news story about Windrush, featuring the well-known calypsonian Lord Kitchener, who, when invited, rather tentatively sings the now famous 'London Is the Place for Me'.

If you listen closely to the Pathé newsreel, you will hear the other men interviewed talking not of arriving to Britain for the first time, but of returning. Many of those onboard Windrush and other ships had been serviceman in Britain during the war. And others, like my father, had worked in the US. These migrants were not all innocent or naïve, as they are often characterised, though post-war Britain was a hostile place far from the idealised ‘Mother Country’ they believed would welcome them.

I went on to write a book of poetry about the Ormonde, to address its omission from the historical narrative. Some poems are based on names I found on the passenger list, including a 9-year-old boy and many women, indicating that women were never a secondary or belated part of this diaspora:

At night, I made myself a dress for England.

All through the rainy months, I stitched by hand,

a copper thimble on my thumb. No more

my threadbare skirt or patched-up pinafore

By candlelight, the pattern was a map

(‘Dressmaker’)

Eventually I did hear about a fellow passenger of my dad’s when the son of Siebert Mattison wrote to me. Mattison’s photo was later taken by the photographer Thurston Hopkins at his home in Birmingham.

Read this next: Hak Baker is taking down the powers-that-be and having fun with it

Windrush has become a powerful metaphor for this migratory period, which ended in 1962 when the Commonwealth Act firmly closed the doors on free migration from the Caribbean. Windrush is a shorthand for the generation of people who arrived, struggled and survived in Britain, and the only moment in Black British history to have made it into the national historical memory.

It has been memorialised in literature and theatre, in TV series, and in numerous exhibitions and public events. It is undeniably an important anniversary around which the Black British community can gather and galvanise. But we should also be mindful that Windrush doesn't obscure the historical truth that there have been Black people in Britain for many centuries. And it is critical to acknowledge Windrush is now marked by the political scandal that bears its name - the shameful and ongoing official machinations of the Hostile Environment, which stripped many Windrush descendants of their citizenship rights.

My father was Afro-Chinese and a professional gambler, facts which also diversify the Windrush story. People of different ethnicities travelled to Britain in this migratory period, and not all worked as bus drivers or factory workers, as is commonly mentioned. Here he is walking in London in the late 1940s. This image reminds me of the last line of James Berry’s poem – ‘So I had begun. Begun in London.’

Hannah Lowe is a poet, memoirist and academic, follow her on Twitter