Features

Features

A deeper African source: How grime and afrobeat is influencing UK jazz

Xaymaca Awoyungbo meets the UK jazz artists who are infusing their music with grime and afrobeat

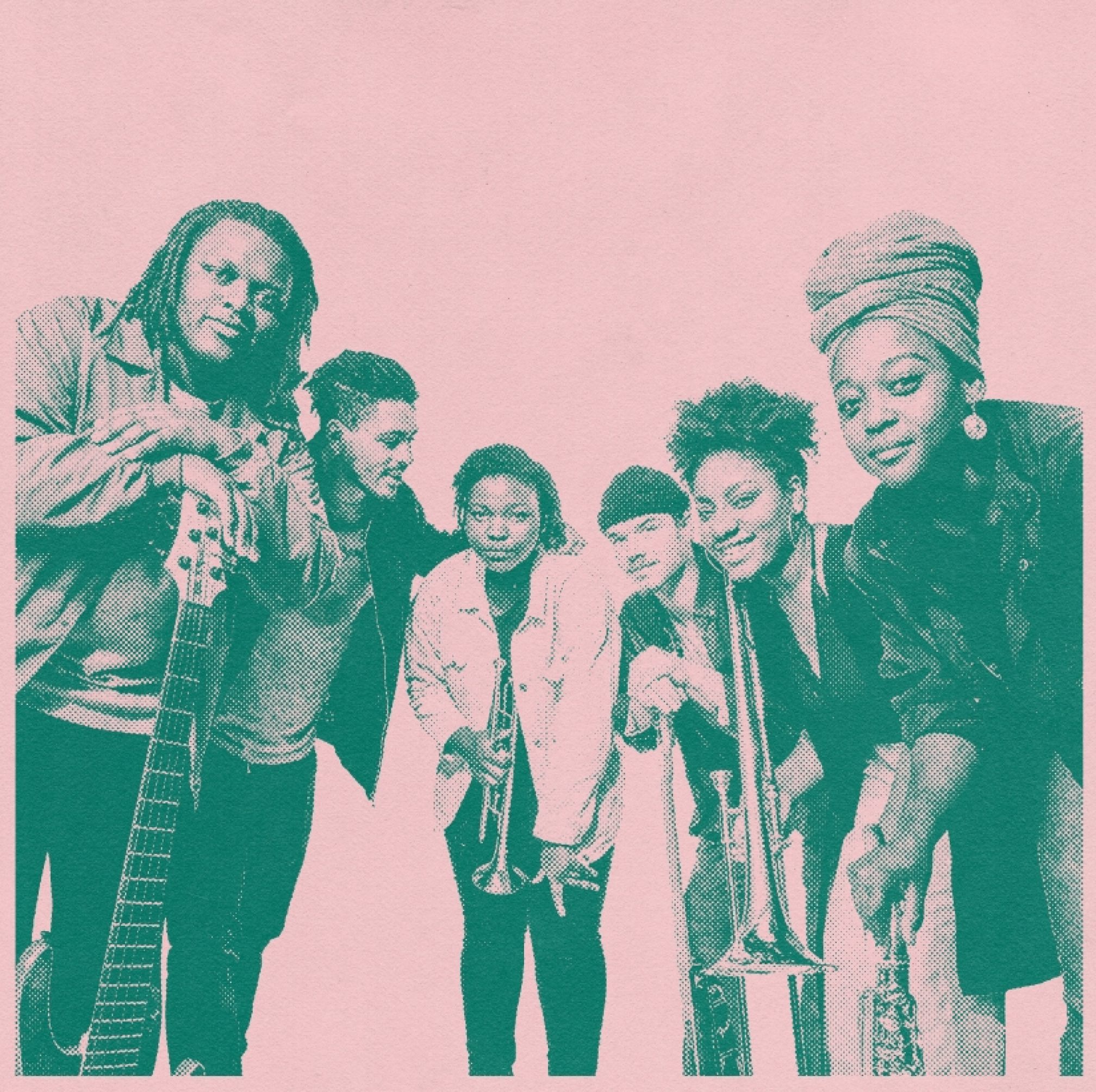

The contemporary jazz scene in the UK doesn’t limit itself in terms of expanding beyond the genre. The new wave of musicians such as Shabaka Hutchings, Moses Boyd, Nubya Garcia, Joe Armon-Jones, KOKOROKO, Ezra Collective and Swindle, to name a few, take influence from grime and afrobeat particularly, helping to create a different yet familiar sound to fans of all three styles of music.

This jazz movement is a representation of multiculturalism in the UK, particularly in its cities. Many of these acts are of an age where they would have grown up during the birth of the UK’s very own genre: grime.

Like UK jazz is doing now, grime fused different genres to create something unique, drawing inspiration from jungle, garage and hip hop. Similarly, they both have a powerful energy built on collaboration. But instead of sets on pirate radio stations like Déjà Vu, many of the jazz musicians played together from a young age at workshops like Tomorrow’s Warriors, an initiative which provides young people from the ages of 11 to 25 with a free musical education. Designed to increase diversity in jazz and engage talented young people, it has developed into a community with success stories returning to teach the next generation.

One of these success stories is saxophonist Shabaka Hutchings of Sons Of Kemet, Shabaka And The Ancestors and The Comet Is Coming. Tomorrow’s Warriors introduced him “to what it was to learn jazz at a young age… The knowledge of what it is to be a jazz musician passed to you by older musicians”.

This type of environment has been lost slightly in grime, since the mass closure of youth clubs – a 51 per cent drop in the overall number of youth centres supported by English local authorities since 2011. Even Tomorrow’s Warriors is fighting to continue providing young people with a free service, since COVID-19 and its ramifications have forced them to start a crowdfunder.

Another one of their success stories, saxophonist, Nubya Garcia, emphasised the importance of the service, saying that “they provided me with a like-minded community, space, jazz education, masterclass - all for free - which is very rare for music initiatives”.

Tomorrow's Warriors sparked a generation of musicians by giving them access to a genre that’s not always associated with young people. This network ensures that young people don’t feel as isolated as artist/producer/DJ Swindle felt when he was growing up. He insists that the education system can do much more since he was “never encouraged to pursue music in any kind of serious way [at school]”.

But testament to the DIY nature of both grime and the current jazz scene, Swindle carved a lane out for himself. That is how he believes that the “idea of jazz living in this underground London space” developed: “[It’s] young people controlling it and finding their own spaces to perform and their own audience to perform to”.

As a result, the music has changed. Artists can mix a range of influences as 2020 Mercury Prize nominee Moses Boyd has done so expertly on ‘Stranger Than Fiction’. The use of horns and atmosphere are reminiscent of early grime; something that Swindle also picked up on and utilised in his track, ‘Drill Work’.

Despite this, the crossover between jazz and grime has largely been limited. Exceptions include the 2017 Jazz Meets Grime radio set on BBC radio 1xtra, Yusseff Dayes and Pa Salieu on the ‘Frontline’ remix and Mez’s ‘One Take Freestyle’ with Kamaal Williams on Tim and Barry TV, as well as Swindle’s back catalogue.

When asked why there isn’t more collaboration between the genres, Swindle, a prolific collaborator himself, said that “it’s a question that I’m trying to answer with my music I suppose. Maybe it’s because people are moving in different circles and are into different things and it doesn’t always seem like an obvious marriage.” Big Zuu echoed this sentiment when I spoke to him, admitting “I don’t really listen to jazz like that”. However, he suggested that more people should be open to collaboration because “jazz can push grime into new directions”.

But Shabaka Hutchings doesn’t quite see it this way. For him, it’s not about genres or labels: “Whether it’s called jazz or it’s called grime, it’s just the way we choose to express ourselves”. He chose to express himself by bringing out D Double E at Sons Of Kemet’s headline show at Somerset House in 2019. He created a space where the grime legend could rap “oo, oo, dirty-ty, /that’s me me” surrounded by a fierce live band.

This highlights the change in jazz and the idea that people play for a different reaction than is traditional. “It’s not seated, dinner table music; people are skanking” said Swindle. Hutchings seconded this and said “there are a lot of things in the music that are being done specifically to invite people in, such as Afro Caribbean rhythms or melody that people can actually comprehend on first listen”. As a result, “you’ve seen a lot more Black people coming out to gigs [and] a lot more young people in general”. Boyd also revealed that “it was a lot more conservative and not as diverse when I was growing up. Now it’s the opposite”.

Effectively, the two scenes are becoming more similar, in terms of the audience demographic. Hutchings also suggested that the sounds are gradually becoming interlinked, pointing to the “intricate” production on Kano’s ‘Hoodies All Summer’ similar to that of jazz.

He doesn’t hear the music in isolation and believes that “once musicians start to hear the deeper connections of the music from a deeper African source, then for me, the genres all go away and [you] start to see how jazz music for instance, can link up with grime”.

The connection between jazz and afrobeat is clearly audible in groups like Ezra Collective and KOKOROKO who draw influence from the genre, helping to draw listeners in. The link is unsurprising, given the heritage of some of the players and the history between the two sounds.

The father of afrobeat, Fela Kuti, studied jazz at Trinity College London in 1959 and afrobeat mixes jazz, among other genres, with Ghanaian highlife. KOKOROKO co-founder, Onome Edgeworth asserted that “when listening to afrobeat you can hear the jazz in it” and that afrobeat’s importance is acknowledged “depending on who you ask”.

Despite this, Ezra Collective member and solo artist, Joe Armon-Jones said “throughout all my time at music college the genre [afrobeat] wasn’t mentioned, even though Fela actually studied at the same college!”

Maybe Armon-Jones’ teachers didn’t think it was worth mentioning but during the 1970s and 1980s Kuti’s music was important as he spoke out against the military government in Nigeria, becoming a voice for young people and the working class.

This meant that for people like Edgeworth, afrobeat “was just the music I grew up with. It was always playing in my house and I was surrounded by a lot of African musicians and artists that worked with my mum. It was normal to us but looking back it was a special thing. We were lucky man, a group of kids that just grew up around live music”. This upbringing has ensured that his band honours tradition: KOKOROKO means “be strong” in Urhobo, a language spoken by the Urhobo people in Southern Nigeria.

But even those who aren’t from that culture cite afrobeat as an influence. People like Emma-Jean Thrackray and Joe Armon-Jones are a testament to a fluidity that exists in the musical and social scenes in London and the UK. Nubya Garcia says that London’s multicultural nature “provides a really beautiful melting pot of inspirations, histories and musical languages”. The afrobeat language has influenced her “rhythmic propulsion”, which is something that she feels very strongly about.

The rise of modern day afrobeats makes this fusion increasingly important too. Armon-Jones doesn’t think “there’s been much crossover between jazz and modern afrobeats” in what he’s heard – the crossover largely taking place between jazz and afrobeat “Fela Kuti style” – he notably collaborated with afrobeat artist, Obongjayar on ‘Self Love’ off of his sophomore album, ‘Turn to Clear View’. Nonetheless, songs like ‘Must Be’ by J Hus infuse jazz with the use of live instruments.

Although jazz and afrobeat are two genres that can be associated with a previous generation, Edgeworth insists that “they’re very much alive. Obviously [they] aren’t at the forefront of popular music now, but elements of them are found everywhere. You listen to Beyoncé or Burna Boy or Kendrick Lamar and you’re hearing jazz and afrobeat. I think more people are more familiar with both genres than we acknowledge and good music will always cut through somehow”. KOKOROKO’s ‘Abusey Junction’ is an example of this. The rhythm and calming nature of the song, touching millions of people from around the world.

For KOKOROKO, and arguably all of the artists within the bubbling jazz scene, “it’s about finding a sound that’s honest and fully exploring that, then pushing that as much as we can. Whatever we’ve consumed is going to be in there. It’s more about respecting those genres [that came before us], doing our study and then pushing ourselves to really honour the innovation and creativity that was shown in them - that’s what we want to replicate”.

Xaymaca Awoyungbo is a freelance journalist. Follow him on Twitter