Features

Features

From The Archives: The Return of Massive Attack

We throw it back to '98 with one of Massive Attack's most revealing interviews ever

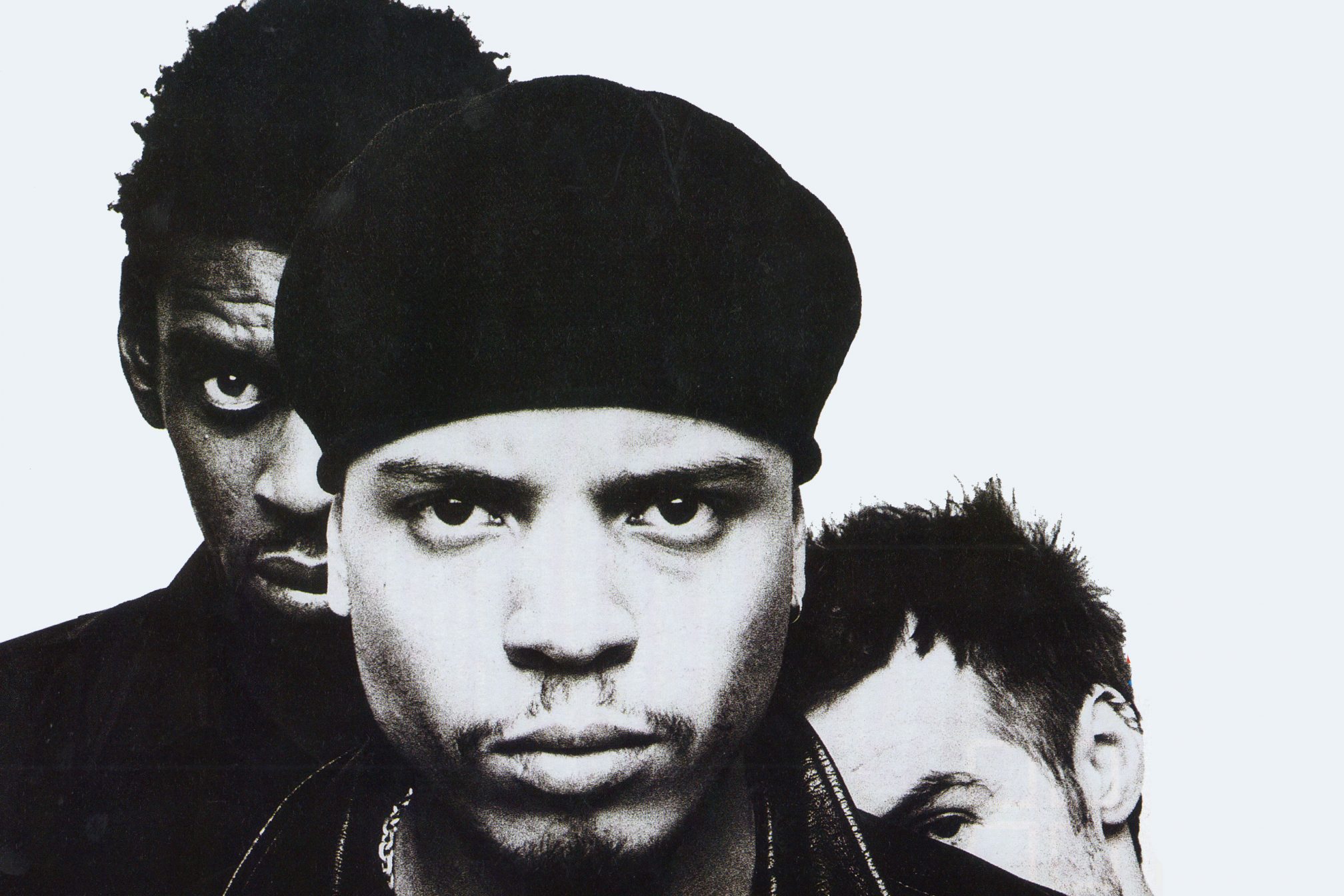

There are three different characters behind Britain's coolest, most influential dance act. One hip hop obsessed b-boy. One DJ who admits they used to judge each others' trainers as harshly as their music. And the third? He's been up all night again, which is why their new album 'Mezzanine' is set in the paranoid hours between night and morning. Is this Massive Attack's most revealing interview ever?

Massive’s 3D takes an exploratory sip from his glass of Martini and crushed strawberries – “Oh man, that’s just ridiculous,” he enthuses-and begins to explain the Mezzanine, the title. “It’s that particular point of the day when the night-before feeling turns into the morning-after feeling,” he says, “and you’re up and you’re with someone and it’s just you two against the World. That idea reflects me, my kind of lifestyle.”

Bearing in mind you’re a Mixmag reader, you might just have been there. Back home from a club in the grey light of dawn. Too much of everything, so you’re never goingto sleep. And there’s nothing to do but sit around, staring at nothing. Watch the air move. Try to ignore that slow, creeping, nameless fear.

In a London hotel room, Grant Marshall, Massive’s Daddy G, laughs. “The mezzanine? I think D spends half his life there. I don’t think he knows whether he’s coming or going. ”

On the Mezzanine, when you’re too fucked to talk and too wired to make any sense, the only thing to do is to step to tunes, and wait for the World to slip away.

Massive Attack have made an album just for you.

These days, the three members of Massive Attack are interviewed separately. Mushroom claims it saves time. 3D says that last time they tried a group interview, they nearly came to blows over the relative merits of Puff Daddy. Massive Attack can agree on everything, he explains in a speedy West Country accent that sounds nothing like his rapping voice. Everything except music.

“We have fun. We experience the world together. We get on really well together, as long as we don’t talk about music. As soon as we talk about music, vye argue.”

It usually comes to;a head in the studio. Massive Attack’s recor.ds may glide out the speakers, the sound of spliffed-up, laid-back contentment, but the making of the classic ‘Blue Lines’ and its follow-up, ‘Protection’ were fraught with disagreements.

“I’m a perfectionist,” says 3D, “so each album’s a bit of a struggle. I listen to all three albums and I think four or five tracks are fucking crap. I intrinsically hate them, but the others like them.” ;

On ‘Mezzanine’, the three worked separately. “Individually recorded because we’re individually minded,” he explains.

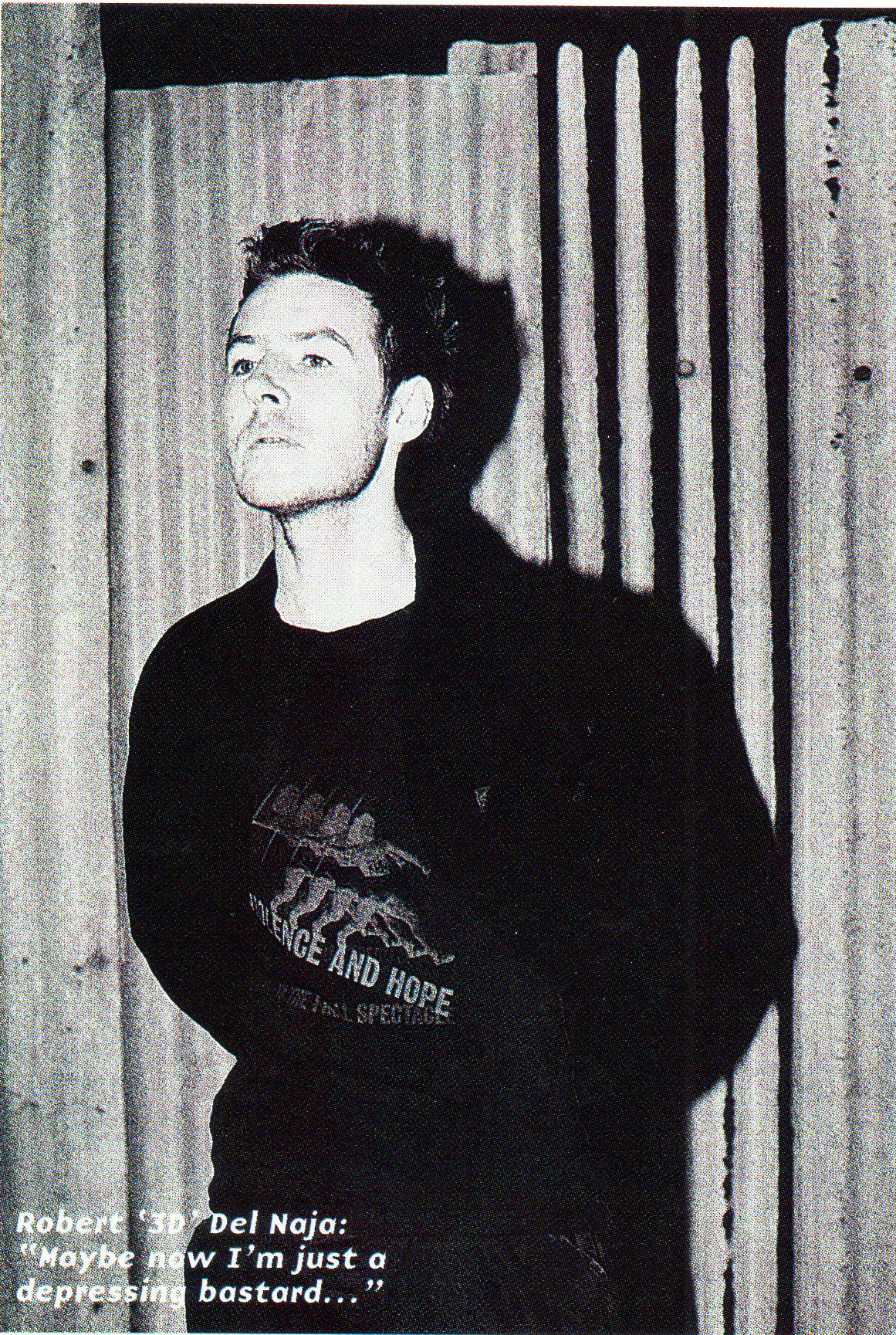

The results are bleaker and heavier than anything Massive have recorded before. Horace Andy’s plaintive voice against a wall of distorted guitars. Breaks that shudder and collapse into scraping noise. Songs about comedowns and boredom and falling out of love. Its workingtitle was ‘Damaged Goods’ because “it felt that way, it felt flawed, itdidn’t fit”. And 3D’s whispersounds more chilling than chilled. On the remarkable ‘Group 4’, his voice is positively evil, whereas before he sounded… “… more like a kid?’; he grins. “I’ve just got older, that’s all. My voice has finally broken. Or maybe now I’m just a’depressing bastard.”

The guitars have spilled over from their live shows. The grinding loops are 3D and Grant’s new wave influences, samples pinched from arty punks like Wire and Bristol’s own Pop Group. But there’s something darker at the heart of ‘Mezzanine’ than just playing with sound. For the first time, Massive Attack sound menacing. 3D dismisses the idea of “pop stars locked in studios, shadowboxing with the Devil” as a cliche, but you sense ‘Mezzanine’ was made against a sombre background. He talks about having “morbid thoughts” and dysfunctional relationships inside and out of the group.

“There’s less stability now. You never know what you’re going to be doing in a month, how you’re going to fit into things, how your mood’s going to be affected by what happens in the studio. Relationships are suffering because of that. In the studio it’s too intense, it’s too difficult, it’s dysfunctional. But that’s the beauty of it. It gives us something in our music. I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

Really? He considers for a second, then laughs.

“Actually, that’s a rash statement…”

“I can remember leaving school one day and some guy had the window of his car down, playing the most diverse music I’d ever heard. I was like, ‘What is this?’ I caught a bus straight down to a shop called Revolver where this big, intimidating sort of guy worked behind the counter. I went up to him, going, ‘Serve me up some of this mad music I’ve just heard!’ I didn’t even know what it was called. I was going, ‘It’s got mad beats! Mad beats!’ The guy behind the counter’s yelling around the shop, ‘What can we sell this kid?’ and he served me up a couple of electro albums.

“There were stickers all over, saying THE WILD BUNCH’. I was like, The Wild Bunch? Are they connected with this mad music? Who are The Wild Bunch?’ The bloke behind the counter turns round and goes, ‘I am The Wild Bunch.’”

Andrew Vowles – the name Mushroom came later, when he worked as a pizza chef – had just been simultaneously introduced to hip hop and Grant Marshall. He was 15, and hooked: “It was just a case of what side of the culture I was going to apply myself to. A bit of spraying? A bit of breaking or DJing?”

The next night, Grant sneaked him into The Dug Out, the Clifton club where the Wild Bunch were early 80s residents. He was adopted as the crew’s junior member. In early photos of the Wild Bunch, he looks impossiblyyoung, intently watching Grant select records, like a kid watching his dad. He’s anxious about what the others said in their interviews – “you’ve talked to the other two and they’ve said something different, haven’t they?”-and his voice, normally so soft it barely registers on tape, puffs up with pride when he takes a step back and begins to talk about their early days.

“When we rolled into a party or a club, there was six of us, all totally mad looking,” he remembers. “We were into extreme dressing. Miles was like a space-age dread, he’d been to Japan and had the maddest clothes. Grant was this seven foot tall zoot-suited guy with a big hat on. D was like something out of a 70s Coppola movie, white shirts and braces and his hair slicked back. Claude was another mad dread, Nellee had the latest designer gear and I had all the stuff from New York at the time.”

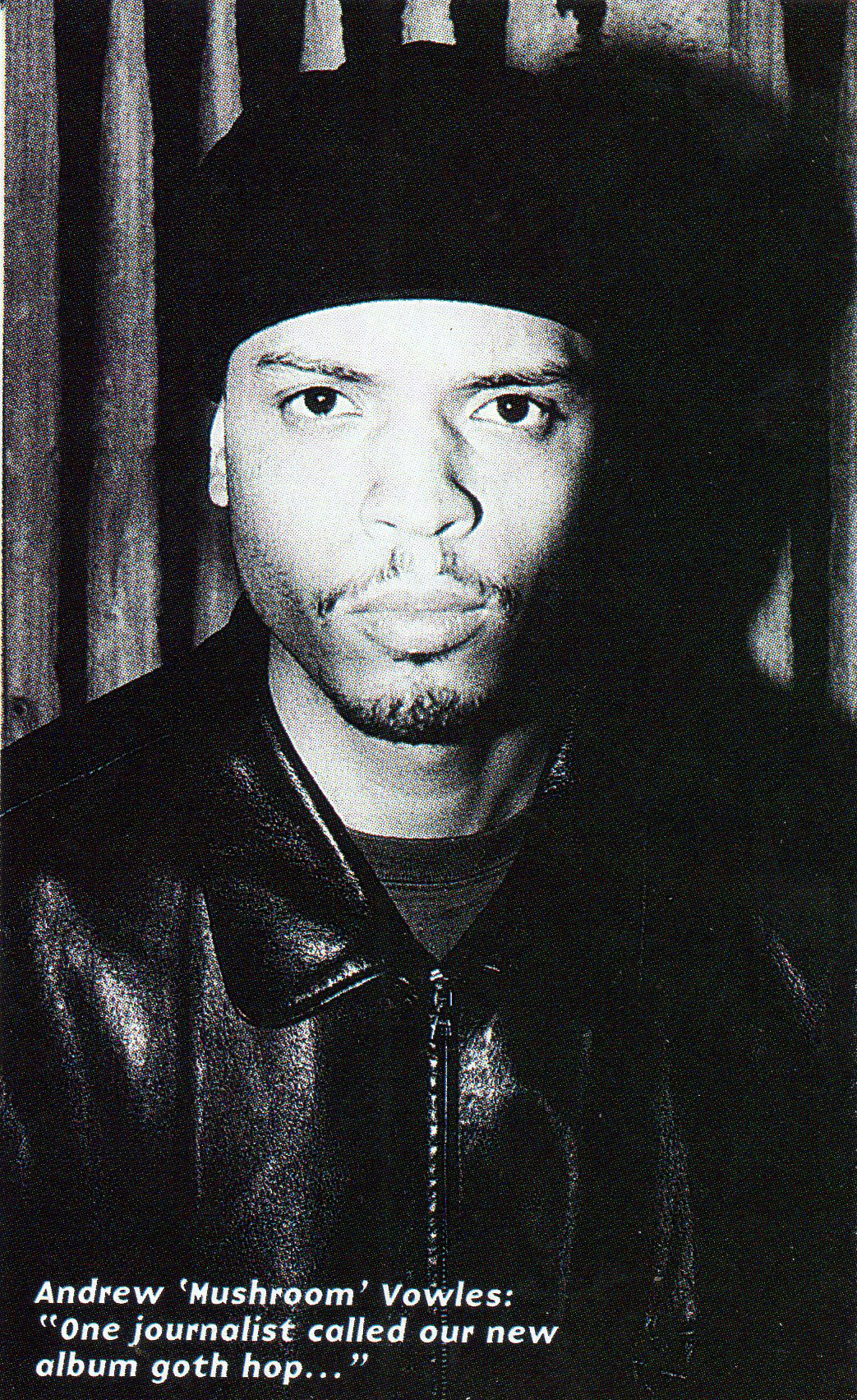

If 3D’s the voice and Grant’s the elder statesman, Mushroom is Massive Attack’s silent, shadowy force: lurking behind his decks on stage, reclining behind designer shades on the cover of ‘Blue Lines’. He never says much in interviews because “I always get asked the same bag of questions they’ve pulled out of the journalists’ vending machine.” And he particularly hates the phrase ‘trip hop’.

“When the Wild Bunch started, we called it lover’s hip hop. Forget all that trip hop bullshit. There’s no difference between what Puffy or Mary J Blige or Common Sense is doing now and what we were doing on ‘Blue Lines’, but no one has the cheek to call them trip hop,” he bristles with indignance. “There was one journalist cheeky enough to call our new album ‘goth hop’. Fuckin’ ridiculous…”

Instead, he thinks ‘Mezzanine’ is a step back from the “electronic studio minefield” that made ‘Protection’ so slick. He claims to be unaware of Massive’s influence on 90s dance culture-“big beat? What’s that?” – because he never reads the press and because Bristol is so isolated from the rest of England. It’s that isolation, he says, that’s shaped the fierce local scene.

“We’re not affected by the latest cultures or trends; when you go out, nobody’s pattingyou on the back saying, ‘Well done, what are you going to do next?’ Like, Portishead is one of the most diverse styles of music that’s ever come out of this country. Geoff Barrow’s a bit of an anorak, right? He enjoys 60s soundtracks, he doesn’t give a fuck really, he wants to do what’s in his mind. Being isolated helped him to develop that. Or Krust. That guy should go down as one of the all-time great pioneer geniuses, like Larry Heard was for house. The music he’s doing is different because he’s isolated in Bristol.”

Ten years on, he’s still obsessed with hip hop: “It’s a pretty obsessive culture, buying the freshest trainers and keeping them fresh, always wanting the freshest, most bumping bit of music.” Talk about guest vocalists and he admits he’d like to work with D’Angelo or Erykah Badu – “but I don’t think the others would be down with that”. And Massive Attack’s greatest achievement?

“Just being true to ourselves. Keeping it real.” Spoken like a true b-boy.

Grant Marshall grins. “I’m a frustrated DJ when it comes down to it. I wanted to be a big DJ, like Nick Warren or Paul Oakenfold. That was on the plans seven years ago. I was going to be Oakie.” Somewhere along the way, the plans got mislaid. He had a brief, early 90s stint as Nick Warren’s DJ partner, dropping house tunes at clubs like Nottingham’s legendary Venus. Fora good few years before the guest DJ circuit developed, he was Bristol’s biggest DJ: credibility and a full house guaranteed if the name‘Daddy G’ appeared on the flyer. Indeed G has always pushed his DJ partners forward: first a forgotten house mixer called West One, later Nick Warren. But house “got a little bit cheesy for me, a bit formularised”, so he concentrated on ‘Blue Lines’.

He’s been DJing since the late 70s, first reggae, then hip hop, then The Wild Bunch, who “used to play a collection of virtually everything from punk to James Brown, just mix those genres of music together.”

People romanticise the early days of The Wild Bunch – writers talk about their “mythic context” -but Grant remembers early Wild Bunch soundclashes, where local punks like Mark Stewart of The Pop Group would “get on the mic, singing farmer’s songs and total obscenities in this real deep voice. ‘Fuck off, yer bums, fuck off!’ over heavy Def Jam beats!”

After years of MCing and DJing, on ‘Mezzanine’, Grant’s taken over Tricky’s role as Massive’s other voice. He admits the transition wasn’t easy.

“I’ve always written lyrics, but they ain’t been that good when I compare them with what 3D does. So quite a lot of my lyrics ended up getting chopped out, because they were… shit, y’know. But playing live, I fuckin’ love it, mate. There’s always that thing, deep down, that you’ve wanted to be in a band and it’s playing out my little fantasy in a way.”

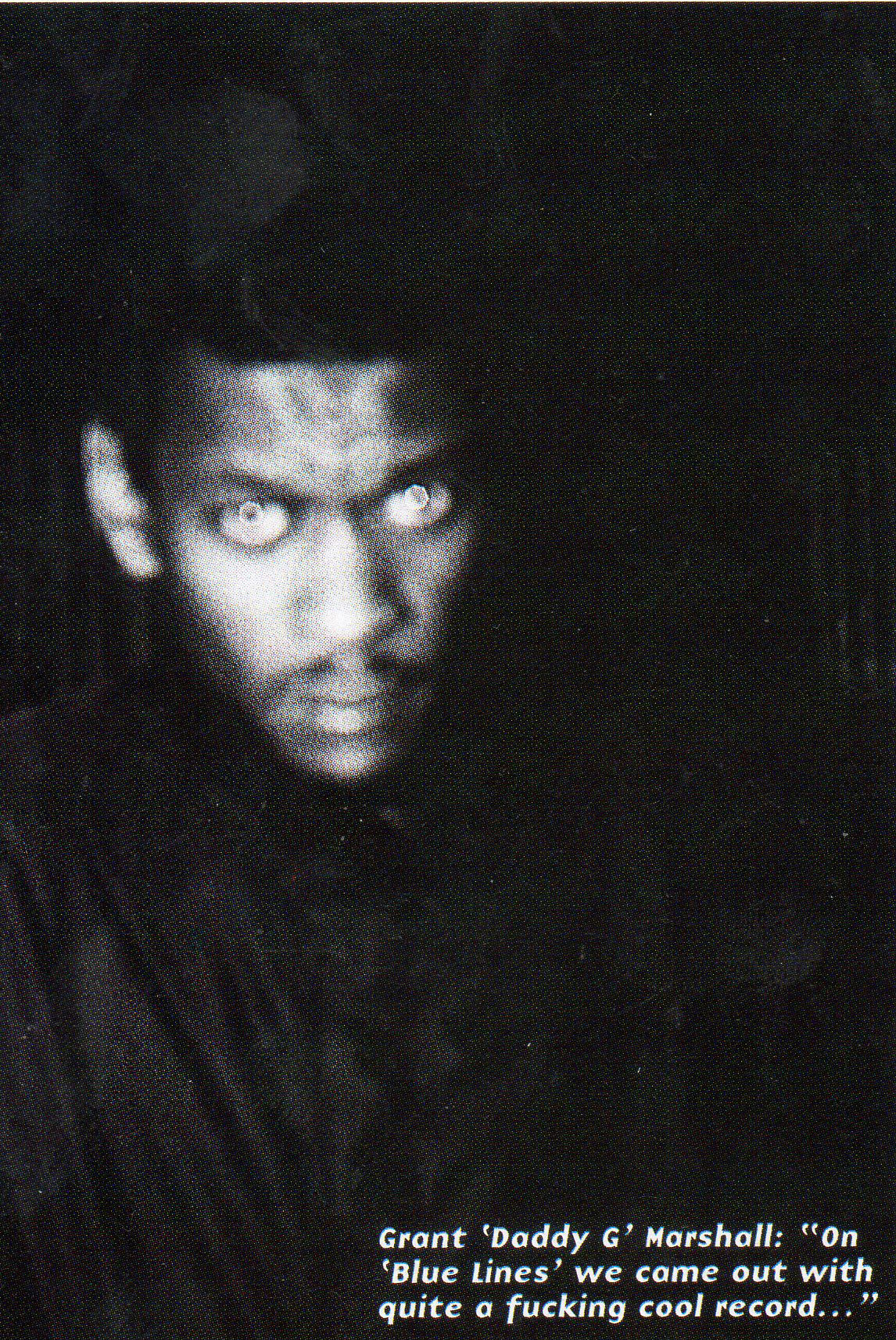

Another fantasy played out: you’re the only successful British hip hop group ever. Like it or not, you started a new genre of music with ‘Blue Lines’. Do you ever think about the influence Massive Attack have had?

There’s a long pause. “Honest?” he asks.

Yeah, honest.

“Yeah, I do. I do think that we were part of a certain movement, kicked off a certain sound in England. The whole thingwas, in Bristol, we were so obsessive, there was this thing about quality control with us. From the early days, you couldn’t wear the wrong trainers or the wrong jeans. It was quite subtle, but it was of the utmost importance. Same with music. On that first album, we were testing each other: ‘Are you down? Are you down?’ And we came out with quite a fucking cool record.”

And now they’ve come out with another. But there’s still one thing bugging 3D.

“The only compromise we’ve ever made is dropping the ‘Attack’ from our name, because of the Gulf War and the pressure we were getting from the radio in particular. We were naive, we didn’t know what the right thing to do was, but we knew it was a compromise. It was a ridiculous, pointless exercise for everyone. Then the other day, I was readingthe paperand it’s all happening again over there. I can just imagine the headline: ‘MASSIVE ATTACK ON IRAQ’, the day before the album’s released. All the major stores turn around and say we’re not stocking the album, it’s in bad taste. You can see it now, can’t you?”

Just another one of those thoughts that spins around your brain on the Mezzanine…

Published in the April 1998 issue of Mixmag, follow Alexis Petridis on Twitter