Scene reports

Scene reports

Live The Dream: How Blackburn dominated warehouse raves in the Summer Of Love

A small collective turned the town into an unlikely, free-spirited rave destination

“They looked evil. It had gone from this joy, elation and pureness and suddenly you saw these people. They looked like Stormtroopers from Star Wars.” Those are the words of filmmaker Piers Sanderson describing the Hardcore Uproar warehouse rave in Nelson, just outside of Blackburn, in 1990. Sick of the Summer Of Love’s arrow working its magic on the Lancashire town for an 18-month period, riot police descended on the party with one aim: to end the raves once and for all. Ravers were hit with truncheons, there was a stampede to get outside and police were pelted with missiles in attempted fightback. “The next week the police had blocked every road going into Blackburn,” Sanderson, who directed the yet-to-come-out documentary High On Hope, adds. It was the beginning of the end for one of the most important, but often overlooked, chapters of acid house history.

Unlike clubs such as Shoom and The Hacienda and M25 raves like Sunrise, Blackburn’s input into the Summer Of Love is less romanticised. Pretty remarkable bearing in mind the parties - held anywhere from vacant warehouses to an abattoir - went from hosting 100 people to 10,000 within a year. Punters came from Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds, even London, and a pre-superstar Sasha played at them. As pointed out by Andrew Barker of 808 State, Blackburn was the ideal destination for ravers when clubs such as The Hacienda closed at 2am. “Everyone was out of their mind and wanting to do something else. Going to Blackburn wasn’t a problem for me or anyone else from Manchester.”

Buoyed by the suppression of Thatcherism and a recession that left warehouses abandoned, a small collective called The Blackburn Self Help Group - including Tommy Smith, Tony Creft and Neil Shackleton - kicked it all off. “Obviously it was anti-authoritarian,” Shackleton says. “You could even say we were anarchists. We were sick and tired of the violence, the tension, the animosity and commercialism of nightclubs. We just wanted to create our own sound and on that ideology, the Blackburn raves were born.”

What made the Blackburn machine so well oiled were the qualities of each member of the collective. Creft with his ability to find the best locations, Smith taking the role of spokesman (he famously defended the acid house movement by declaring he was “high on hope” on Granada TV), Shackleton booking the DJs and two dedicated soundsystem builders. “If you could transpose that working ideal to any modern British business or business practice, it’s perfect,” Piers Sanderson says. “They were all experts in their own ways.”

Their starting point each week was The Sett End, a now-closed pub on North Road. Despite a license permitting a capacity of 300, there would be more than double packed inside until 2am, while hundreds in cars waited outside for the convoy - and usually a decoy - to head to the venue. “[Once there] everyone would abandon their cars on the hard shoulders of motorways,” Sanderson remembers. “Then you’d get out of your car and run to get into the warehouse and wait for the soundsystem and generator to be set up. You could just hear this murmur of voices and it’d be pitch black. Then ‘boom!’, the first needle would drop on the record and everybody would go ballistic.”

A big change in dynamics was the Live The Dream rave in the village of Tockholes on September 16, 1989, attracting around 3,000 people. “That changed it completely,” Shackleton says. “There was nothing stopping us at that time. This is when we then started to go onto these big industrial, commercial estates.”

Obviously with bigger numbers and success comes more attention. Similar to the tabloid newspapers’ acid house fearmongering, Blackburn’s local paper once wrote that the parties had half-naked women and ecstasy wrappers on the dancefloor. Although this backfired and only heightened the popularity as Shackleton says “you couldn’t write a better flyer than that so we were laughing at the time.”

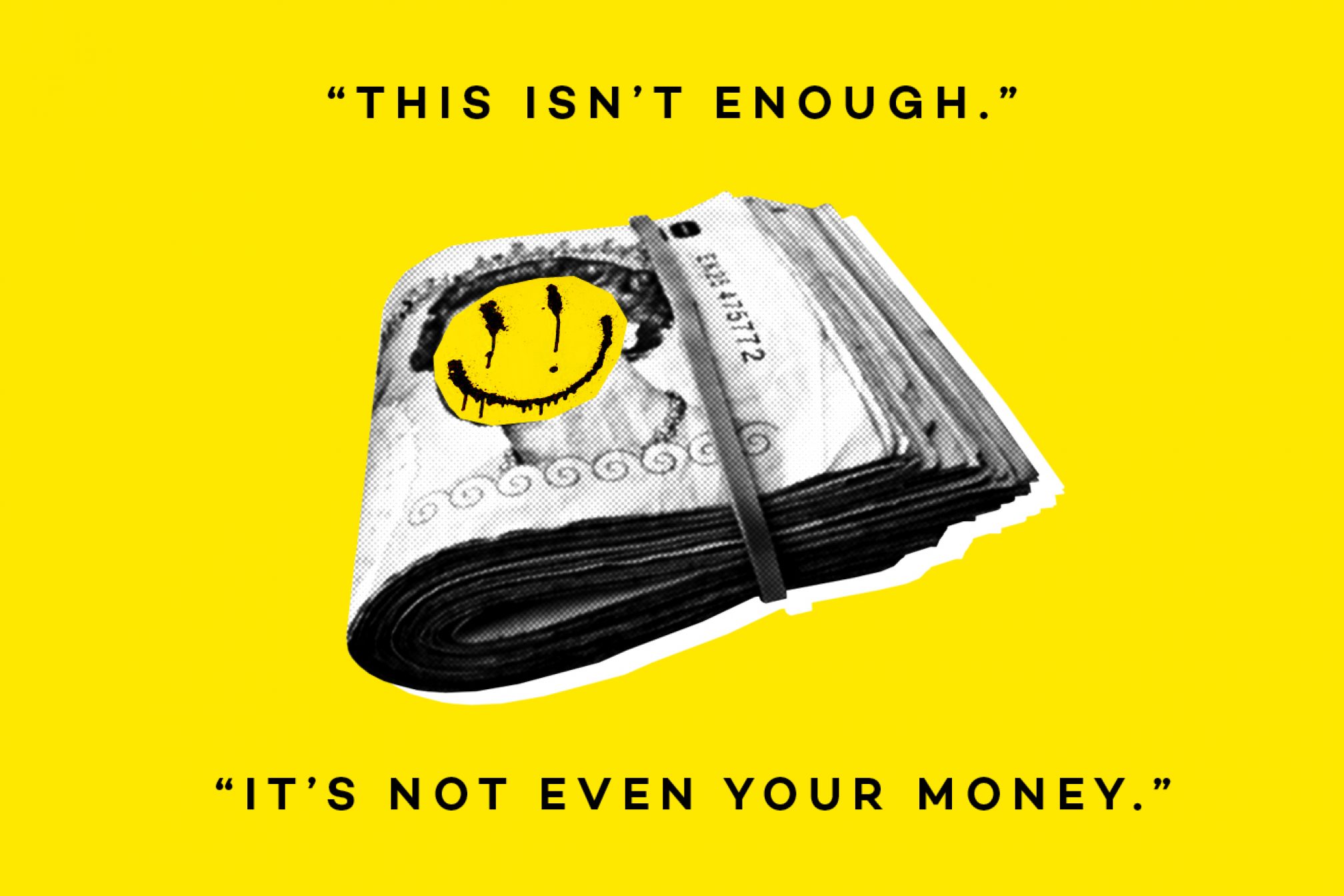

On top of the media’s negativity and before the police started seriously cracking down on the parties, gangs from nearby Manchester and Salford sensed a form of income and started to demand the takings. “The problem with lawlessness is that you attract people who want to take advantage,” Sanderson says. “[The Salford gangsters] just took over the door. They would be in there counting the money and saying ‘this isn’t enough.’ Tommy [Smith] and Tony [Creft] would look at them like it’s not even your money.” Police also ended up arresting the guys behind making the soundsystems and keeping Smith in prison for almost a year before he had a trial. Sanderson adds: “When he went to court it all collapsed. There was no case. It was all just a way of trying to keep people in. He couldn’t get out to organise the parties and that’s all they cared about.”

Along with the media attention, there’s a theory that gangsters getting involved led to the police adopting a stricter approach. Once happy to be dealing with wide-eyed ravers and traffic instead of booze-fueled violence, they were on a mission to pull the plug on the parties by the time the Hardcore Uproar rave - with up to 10,000 people in attendance - in Nelson happened. Suddi Raval of acid house group Together, who were there to record crowd samples for a track (named ‘Hardcore Uproar’), described the moment police entered the building: “They came from every direction, hundreds of them and had the intention of scaring everybody to send a message: ‘do not come back here again’. It was quite horrific.”

With parties being thrown in Blackburn near-on impossible by this point, organisers turned to Leeds, where a rave in July 1990 led to the UK’s biggest mass arrest - 836 - ever. One of those arrested was DJ Rob Tissera for encouraging ravers to keep riot police outside of the venue. Unsurprisingly, the incident made national news and the attendees interviewed cited police brutality.

An incident like that was evidence the police weren't messing around. The organisers were well aware of the repercussions were they to go ahead with further parties and so the scene fizzled out. It'd tasted the glory, though, having an upper hand on and foiling the authorities for the majority of time they were going. "They were just local people who knew the town and were really determined," Sanderson says. "In the end you were getting up to 10,000 people and they were still getting them past the police. It’s just incredible."

Dave Turner is Mixmag's Digital News Editor, follow him on Twitter